Nature's First Farmers: 50 Million Years of Ant Agriculture

TL;DR: Octopuses achieve perfect camouflage despite being colorblind through distributed neural networks, light-sensing proteins in their skin, and millions of individually controlled color cells called chromatophores. Their skin essentially sees and decides autonomously, without requiring brain input.

Watch an octopus transform from mottled brown to coral pink in the blink of an eye, and you're witnessing one of nature's most confounding tricks. These eight-armed shape-shifters can match any background with photographic precision - rocky outcrops, sandy bottoms, even the dappled shadows of a coral reef. The twist? They're completely colorblind. So how does an animal that can't see color become nature's most accomplished color-matcher?

The answer rewrites what we thought we knew about vision, intelligence, and the very nature of seeing.

For decades, scientists assumed octopuses possessed sophisticated color vision to explain their camouflage abilities. Then in the 1970s, researchers dissected the eyes of Octopus vulgaris and discovered something startling: a single visual pigment. Just one. Humans have three types of color receptors; mantis shrimp have sixteen. Octopuses have one R-type opsin that absorbs light in the 360-475 nanometer range. By every measure, they're as colorblind as a dog.

Yet these animals execute color changes in under 0.3 seconds, matching hues they theoretically can't perceive. When marine biologists at Birch Aquarium track their resident octopuses, senior aquarist Maddy Tracewell sees the contradiction daily. "We naturally want to attribute those changes to emotions," she explains, "but rather there are certain color patterns that correspond with certain behaviors."

The behaviors are real. The mechanism was a mystery.

The breakthrough came from an unexpected direction. In 2015, researchers reported finding rhodopsin - the same light-sensitive protein that enables vision in eyes - embedded throughout octopus skin. Not near the eyes. In the skin itself. The tissue was seeing.

Think about that for a moment. Your skin detecting light independently of your eyes, processing visual information without your brain's involvement, making split-second decisions about what color you should be. It sounds like science fiction, but for cephalopods, it's Tuesday.

Octopus skin contains the same light-sensing proteins found in eyes, allowing it to detect and respond to light without any input from the brain.

These aren't simple light detectors, either. Recent studies have identified multiple types of opsins distributed across octopus skin, each tuned to different wavelengths. The skin isn't just sensing brightness - it's conducting a wavelength analysis, a crude but functional form of color detection happening in parallel across millions of cells.

When University of Chicago researchers examined squid skin cells, they found the cells responded directly to light exposure by changing their pigment expression. No brain required. The skin was making its own decisions about camouflage in real time.

The mechanics of cephalopod skin read like an engineer's fever dream. Three distinct cell layers work in concert, each contributing a different optical effect.

The top layer contains chromatophores - pigment sacs surrounded by radial muscles. Each chromatophore is stuffed with red, yellow, or brown pigment, and when the muscles contract, the sac flattens and expands like a balloon being squashed. Expand the sac, the color becomes visible. Relax the muscles, it shrinks to an invisible pinpoint. An octopus has millions of these across its body, each individually controllable.

Beneath the chromatophores sit iridophores - cells packed with reflective protein platelets that act like biological mirrors. By adjusting the spacing of these platelets, iridophores can reflect specific wavelengths, producing metallic blues, greens, and iridescent patterns. They're the reason cuttlefish can shimmer like oil on water.

The bottom layer holds leucophores - white reflecting cells that scatter all wavelengths equally. They provide the base canvas, a blank white screen that makes the colors above pop with greater intensity.

Together, these three layers can produce virtually any color, pattern, or texture found in the ocean.

Here's where it gets genuinely strange. An octopus has nine brains - one central brain in its head, and eight smaller ganglia, one in each arm. But even that undersells the distributed nature of octopus intelligence. Roughly 60% of an octopus's neurons live in its arms, not its head.

Each arm can taste, touch, and make independent decisions. Severed octopus arms have been observed reaching for food and even attempting to pass it to a mouth that no longer exists. The arms aren't just following orders - they're running their own programs.

"Roughly 60% of an octopus's neurons live in its arms, not its head. The arms aren't just following orders - they're running their own programs."

- Marine Biology Research

The skin operates the same way. When researchers at the University of Chicago sequenced the octopus genome in 2015, they found massive expansions in genes related to neural development and skin sensing. The genome wasn't optimized for centralized processing. It was built for distributed decision-making.

Each patch of skin is essentially autonomous, sensing local light conditions and responding accordingly. The central brain doesn't micromanage every chromatophore - it sets general directives, and the skin fills in the details. It's less like a puppet being controlled and more like an orchestra following a conductor's tempo while each musician plays their own part.

So if octopuses can't see color, what are they actually matching? The answer appears to be brightness, or more technically, luminance. A 2024 study using spectroradiometers to measure gloomy octopus camouflage found they excel at matching the lightness of backgrounds but often miss saturation. They get the brightness right, which to a colorblind predator like a shark, is good enough.

This makes evolutionary sense. Most oceanic predators - sharks, seals, large fish - are themselves colorblind or have limited color vision. They hunt by detecting contrast, the difference between an object's brightness and its background. An octopus that matches luminance patterns becomes effectively invisible to these hunters, regardless of whether the hues are perfect.

But there's a twist. Some cephalopod predators - certain fish, marine birds - do have color vision. So how do octopuses fool them?

Enter chromatic aberration, one of the most elegant solutions evolution has devised. Different wavelengths of light refract at different angles when passing through a lens. Cameras compensate for this; it's why cheap lenses produce color fringes. But octopuses may exploit it.

Their peculiar off-axis, dumbbell-shaped pupils could allow different colors to focus on different parts of the retina. By shifting focus, an octopus might sense which wavelengths are present without actually seeing color the way we do. It's like identifying a song by its tempo and key without hearing the melody - crude, but functional.

The pigments themselves reveal millions of years of evolutionary refinement. The primary pigment in chromatophores is xanthommatin, a structurally complex ommochrome that shifts color depending on its chemical state and concentration. Until recently, studying it required extracting tiny amounts from actual cephalopods - about 5 milligrams per liter of processed tissue.

Then in 2025, researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography genetically engineered soil bacteria to produce xanthommatin at industrial scales - 1 to 3 grams per liter, a thousandfold improvement. Bradley Moore, the marine chemist who led the work, describes it as a biological feedback loop: "We're asking the microbe to make a material for us, and at the same time we're making sure we give something to the microbe so it will want to make this material for us."

Scientists have engineered bacteria to produce octopus camouflage pigment at 1,000 times the yield of traditional methods, opening new possibilities for color-changing materials.

The breakthrough does more than just supply research labs. It opens the door to biomimetic materials - human-made fabrics and surfaces that change color on demand, inspired by but potentially surpassing cephalopod camouflage.

Perhaps the most revealing experiments involve sleeping octopuses. Researchers studying octopus sleep cycles discovered they exhibit two distinct phases: quiet sleep and active sleep. During active sleep, octopuses cycle through color changes, textures shifting, patterns rippling across their skin like dreams playing out on a living canvas.

They're not responding to their environment - they're curled up in dens, eyes closed. The changes are autonomic, the skin executing camouflage routines without conscious input. It's as if the camouflage system is so fundamental to octopus biology that it continues running even when the central brain is offline.

This autonomy comes at a cost. A PNAS study measured the metabolic burn of color change and found it's staggeringly high. Octopuses are sprinters, not marathoners. They hunt in short, explosive bursts, then retreat to dens to recover. Their nocturnal lifestyle and reclusiveness aren't personality traits - they're energy management strategies.

Military researchers and materials scientists have been studying cephalopod camouflage for decades, trying to reverse-engineer it. Early attempts at adaptive camouflage required cameras, processors, and power-hungry display systems. They were bulky, slow, and nothing like the elegant simplicity of octopus skin.

The new approach focuses on materials that respond directly to light, eliminating the need for central processing. Researchers have developed polymer films embedded with photosensitive molecules that change opacity based on local illumination - a direct analog to skin opsins. Others are working on metamaterials with tunable reflectivity, mimicking iridophore function.

The goal isn't military invisibility cloaks, at least not primarily. The real applications are more mundane and more revolutionary: buildings that adjust their thermal properties based on sunlight, reducing energy consumption; medical sensors that change color to indicate infection or inflammation; packaging that shows when food has spoiled.

In 2025, a team at MIT demonstrated event cameras that mimic cephalopod vision - single-wavelength sensors that infer color through motion and chromatic aberration. The cameras are faster and more efficient than conventional RGB sensors, proving that the octopus's "limitation" is actually an optimization.

"We're asking the microbe to make a material for us and at the same time we're going to make sure that we give something to the microbe so it will want to make this material for us."

- Bradley Moore, Marine Chemist, Scripps Institution of Oceanography

The octopus camouflage system reveals something profound about evolution's approach to engineering problems. We assume sophisticated outcomes require centralized control - a powerful brain analyzing inputs and issuing precise commands. Octopuses prove otherwise.

Their solution is radically distributed: millions of semi-autonomous sensors and actuators, each responding to local conditions, coordinated by general principles rather than specific instructions. It's closer to how ant colonies function than how we typically think of animal behavior. There's no master neuron computing the perfect camouflage pattern. There's a diffuse network of simple units that, collectively, produce complexity.

This architecture has advantages. It's fault-tolerant - damage to one area doesn't crash the whole system. It's scalable - add more skin, get more processing. It's fast - decisions happen locally without round-trip delays to a central processor.

It also challenges our assumptions about consciousness and intelligence. Does an octopus "know" what color it is? Does it have a mental image of how it looks? Or is camouflage something that happens to it, executed by autonomous systems below the threshold of awareness?

Senior aquarist Maddy Tracewell suspects the latter. "When they sleep, they are usually tucked away in their den and not very interactive," she notes. The color changes during sleep suggest camouflage is more reflex than decision, more autonomic than conscious.

For all we've learned, fundamental mysteries persist. How do octopuses match complex patterns - the dappled light through kelp, the mottled texture of a coral head - when their skin sensors can only detect local light levels? Pattern recognition requires comparing regions, understanding spatial relationships. How does distributed processing accomplish that?

Some researchers propose proprioception - the sense of body position - plays a role. If an octopus can feel which chromatophores are expanded, it could use that tactile feedback to adjust patterns, essentially feeling its way to the right camouflage.

Others point to circadian mechanisms discovered in octopus skin. In 2019, researchers found skin cells maintain their own biological clocks, independent of the brain. These cellular timers could coordinate pattern generation across distributed skin regions, synchronizing color changes without central oversight.

The computational tools to study this are only now emerging. In 2024, scientists developed CHROMAS, a machine learning pipeline that can track individual chromatophores in video footage, analyzing their dynamics frame by frame. For the first time, researchers can quantify exactly how patterns emerge, which chromatophores fire in sequence, how waves of color propagate across skin.

New machine learning tools can now track individual color-changing cells in real time, revealing the hidden patterns of how camouflage emerges across octopus skin.

Early results are tantalizing. Chromatophore activation doesn't spread uniformly - it follows specific pathways, suggesting underlying neural architecture that's only beginning to be mapped. The skin isn't just responding to light; it's processing information in ways we don't yet understand.

There's an urgency to this research beyond pure curiosity. Cephalopod populations are changing as oceans warm and acidify. Some species are expanding their ranges; others are struggling. Their camouflage abilities, so finely tuned to current ocean conditions, may face challenges in altered ecosystems.

Researchers are also discovering that camouflage can serve as a biomarker for environmental stress. Cuttlefish exposed to pollutants show disrupted color change patterns. Their skin, so sensitive to light, also picks up chemical signals. Abnormal camouflage behavior might be an early warning system for ocean health, a living sensor network monitoring conditions we can't easily measure.

The same adaptability that makes cephalopods successful could be their vulnerability. If camouflage is autonomic, hardwired by evolution to respond to specific light patterns and substrates, what happens when those patterns change? When coral bleaching turns reefs white, when algae blooms alter water clarity, when artificial light pollutes the ocean's natural rhythms?

We don't know yet. But octopuses have survived five mass extinctions. They've adapted to every ocean environment from tidal pools to the deep sea. Betting against their ingenuity seems unwise.

Walk through an aquarium and watch the octopus tank long enough, and you'll see it happen - the moment when an octopus, perfectly still against a rock, suddenly registers your presence and shifts. Not just color but texture changes, skin that was smooth erupts into papillae, becoming spiky and rough. The transformation is so complete you question whether you're looking at the same animal.

You are. You're just seeing what hundreds of millions of years of evolution can accomplish when the problem is survival and the solution is becoming invisible.

The octopus isn't thinking about camouflage the way you might think about changing clothes. It's not making aesthetic choices or considering options. It's doing what it does, what its body knows how to do, what countless generations of selective pressure have refined into something approaching perfection.

That it accomplishes this without color vision, without centralized control, without even fully understanding what it looks like - that's not a limitation. That's the genius.

Because in the end, the octopus doesn't need to see itself. It needs to disappear. And for that, it has become something more than an animal that changes color. It's become a living question about the nature of intelligence, the boundaries of consciousness, and what it means to truly see.

The answer, like the octopus itself, keeps changing every time you think you've found it.

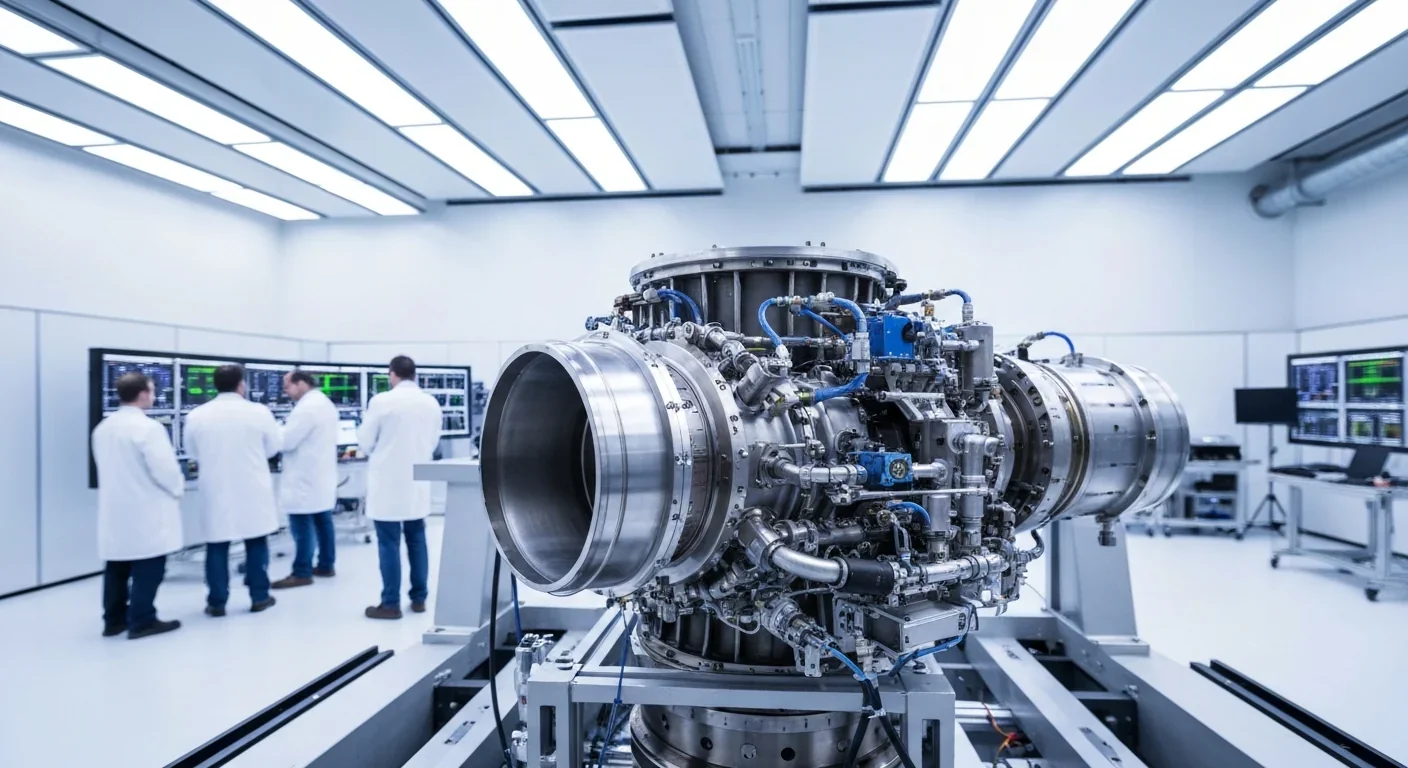

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

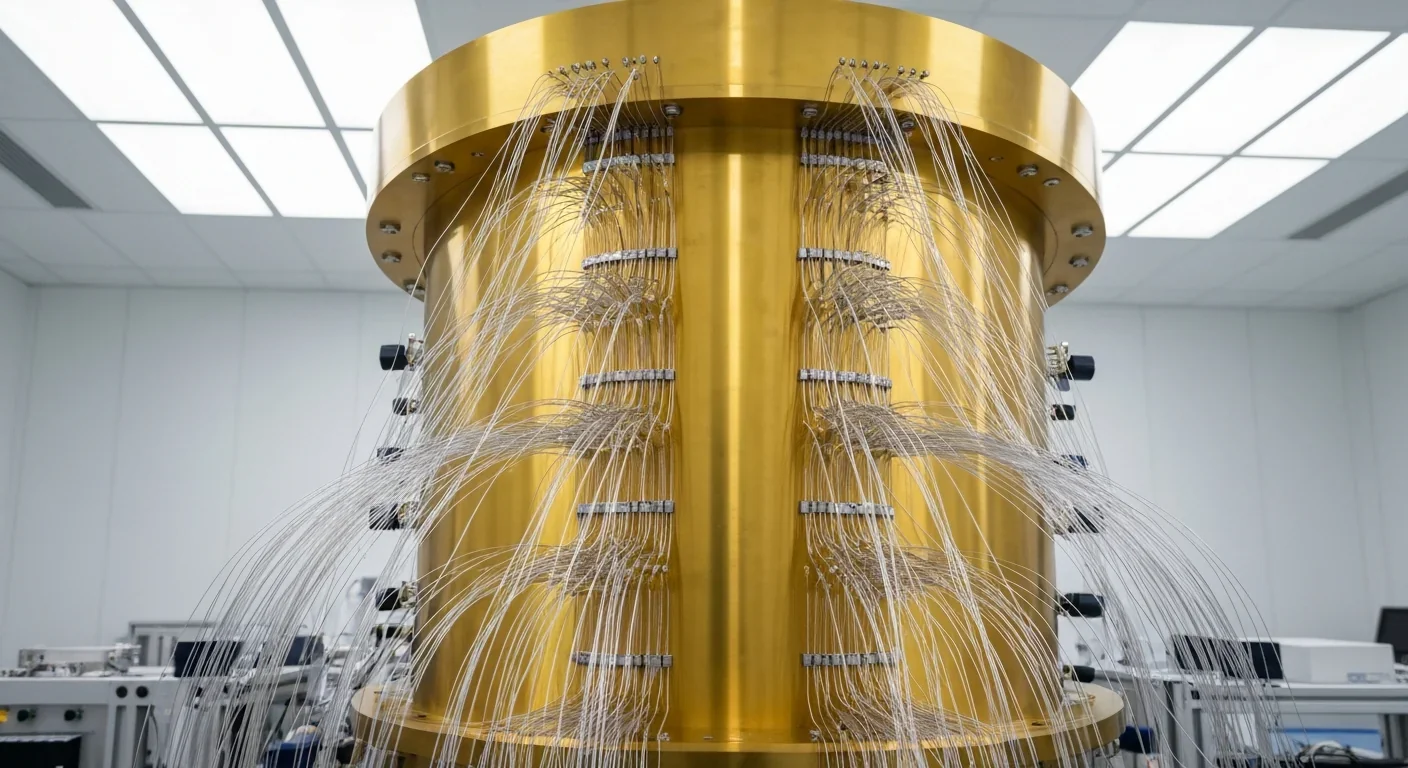

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.