Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Birds construct sophisticated nests through embodied cognition - a distributed problem-solving system combining evolutionary adaptation, environmental feedback, and learned behavior - demonstrating that engineering brilliance doesn't require conscious understanding.

A tailorbird pierces a leaf with its beak, threading spider silk through the hole like a needle through fabric. Within hours, it's stitched together a living cradle for its eggs. The bird has never taken an engineering course, can't calculate load-bearing ratios, and possesses no conscious understanding of structural mechanics. Yet it's just built something that would challenge a human architect.

This isn't magic, and it's not quite instinct in the way we usually think about it. Bird nest construction represents one of nature's most fascinating puzzles: how do creatures with brains the size of walnuts consistently produce architectural marvels that optimize for structural integrity, thermal regulation, and predator defense - all without blueprints, math, or even awareness of what they're doing?

The answer reveals something profound about intelligence itself. Because birds don't solve engineering problems the way humans do. They've evolved something potentially more elegant: a distributed problem-solving system where evolution, instinct, environmental feedback, and learning converge to produce solutions that often rival or exceed human engineering.

For generations, we've called nest-building "instinctive," as if that explained anything. But neuroscientist Mark Blumberg argues we should abandon the word instinct entirely because it obscures more than it reveals.

"I don't use the word instinct. Once you have that many definitions, the word no longer has a useful meaning. I use the phrase 'species-typical.' It's a behavior that is typical to a species."

- Mark Blumberg, Neuroscientist, University of Iowa

This seemingly pedantic distinction matters. When we say nest-building is instinctive, we imagine birds as biological robots executing genetic code. The reality is far more interesting. Birds build nests through what scientists now recognize as embodied cognition - intelligence distributed across brain, body, and environment rather than residing solely in conscious thought.

Consider the Southern Masked Weaver, which constructs elaborate suspended nests from grass. Researchers filming weavers in Botswana discovered something unexpected: each bird developed its own building style. Some consistently built left-to-right, others right-to-left. More tellingly, birds dropped fewer grass blades with each successive nest they built.

"If birds built their nests according to a genetic template, you would expect all birds to build their nests the same way each time. However, this was not the case."

- Dr. Patrick Walsh, University of Edinburgh

Even for birds, practice makes perfect.

So if it's not pure genetic programming, how do birds achieve structural soundness? Recent research from Harvard's School of Engineering reveals an elegant answer: they exploit the physics of entanglement.

Most people assume bird nests stay together through adhesives - mud, saliva, or sticky materials binding twigs together. But L. Mahadevan's team discovered the real secret: stiff sticks entangle in ways that distribute and resist force, creating structures that withstand continuous disturbance from wind, weather, and restless chicks.

The key lies in aspect ratio - the length-to-diameter relationship of building materials. Using X-ray tomography and steel-rod experiments, researchers found that high aspect ratios (long, thin materials) create dramatically stronger entanglement than short, thick materials.

Contrary to common intuition, stiff and straight rods can entangle themselves - if they are long or thin enough. This principle governs everything from polymer physics to bird nest architecture.

This isn't conscious material selection. Birds don't calculate aspect ratios. Instead, evolution has tuned their preferences toward materials that naturally possess optimal mechanical properties. When a bird instinctively chooses a long, flexible grass blade over a short, thick twig, it's implementing millions of years of trial-and-error engineering compressed into a behavioral preference.

Pigeons nesting near construction sites sometimes incorporate scrap wire with aspect ratios around 10:1 - precisely the range that maximizes entanglement. They're not doing physics. They're doing what feels right, and what feels right has been shaped by generations of nests that either stood or fell.

Bird nest construction operates as a dynamic feedback system. Birds don't build according to predetermined plans - they adjust continuously based on real-time sensory input.

The rufous hornero, which builds oven-shaped mud nests in South America, demonstrates this beautifully. When horneros build near lateral structures like branches or walls, they place the nest entrance on the same side as that structure 62-76% of the time - significantly more than chance.

Why? The external structure provides tactile and visual cues that guide construction. The bird isn't thinking "I should align my entrance with this branch for structural support." It's responding to environmental signals that generations of evolution have linked to successful outcomes.

In Arctic regions, scrape nests must balance competing thermal constraints. Too deep, and eggs suffer from ground cold where permafrost lurks centimeters below. Too shallow, and wind carries away vital heat. Studies show birds adjust nest depth within 24 hours of temperature changes, maintaining optimal conditions through behavioral feedback rather than calculation.

Eggs in properly adjusted scrape nests lose heat 9% more slowly than eggs on bare ground - jumping to 34% when lined with vegetation. That's precision engineering achieved through procedural memory and environmental response.

Cliff swallows transform mud and saliva into natural cement, creating gourd-shaped nests that cling to vertical cliff faces. These structures can reach 1.5 meters high, housing entire colonies. Each nest consists of thousands of mud pellets, carefully shaped and positioned to create chambers that dissipate heat, seal out wind, and provide insulated micro-environments.

The engineering is remarkable. Mud walls up to 3 centimeters thick harden into permanent structures that can last years. The birds mix saliva with mud to enhance adhesive properties - a technique eerily similar to ancient human construction methods that added organic binders to clay.

How do cliff swallows know to do this? They don't "know" in any conscious sense. They're following behavioral sequences triggered by hormonal changes during breeding season, refined through observation of colony-mates, and adjusted based on tactile feedback as they work.

Robins employ similar mud-and-saliva construction but shape cup nests instead of enclosed chambers. Research shows birds regularly test structural integrity by applying pressure and adjusting loose materials - a kind of real-time improvisation without conscious planning.

Weaverbirds represent perhaps the most spectacular avian engineers. Male weavers construct elaborate suspended nests that dangle from branch tips, swaying in the wind but rarely falling.

The weaving technique is genuinely sophisticated. Birds loop grass blades around branches, tie knots, and create interlocking patterns that distribute tension across the entire structure. Some species add entrance tubes that spiral downward, making it nearly impossible for predators to reach eggs.

The baya weaver of South Asia builds retort-shaped nests with long entrance tubes, often suspended over water. The sociable weaver of southern Africa takes communal construction to extremes, building enormous apartment complexes that can house hundreds of pairs and weigh several tons.

These massive structures persist for decades, with new generations adding chambers and maintenance. They create their own microclimates - cooler in scorching days, warmer during cold nights. The weavers aren't consciously engineering climate control systems. They're building according to species-typical behaviors that evolution has refined because birds in well-regulated nests produced more surviving offspring.

The weaver studies revealed individual variation and improvement with practice, but how much of nest-building is learned versus genetically inherited?

The answer: both, inextricably intertwined. Young birds observe parents and refine techniques through trial and error. But they start with innate predispositions - slight biases in the system that guide them toward species-typical behaviors.

It's similar to human language acquisition. We're not born speaking English or Mandarin, but we are born with neural architecture primed for language learning. Birds aren't born knowing exactly how to build nests, but they're born with perceptual and motor biases that make certain actions feel natural and satisfying.

A border collie doesn't need to be taught to herd - but it does need training to refine that instinct into useful behavior. Similarly, birds come equipped with rough templates and an urge to build during breeding season. Experience sharpens those rough templates into functional structures.

Ring doves provide a fascinating example. Research shows male nest-building depends on prospective mate behavior rather than hormonal mechanisms alone. Social cues trigger construction, not just internal chemical signals. Intelligence emerges from the interaction between organism and environment.

Birds employ an astonishing array of construction materials: grasses, mud, sticks, leaves, moss, lichen, spider silk, animal hair, snake skin, and even cigarette butts. Each material offers specific mechanical properties, insulation values, and functional benefits.

Spider silk deserves special attention. Hummingbirds incorporate spider webs into their tiny cup nests, and the elasticity is crucial. As chicks grow, the nest expands while maintaining structural integrity - like biological bungee cords holding everything together.

Some cavity-nesting species incorporate snake skin as a predator deterrent. A 2024 study found birds building in cavities are six times more likely to use snake skin than birds building cup nests. The presence of snake skin correlates with reduced predation rates - approximately 22% fewer nest raids.

Birds that incorporate snake skin into cavity nests experience 22% fewer predator attacks. This represents evolved chemical warfare - unconscious strategy shaped by generations of differential survival.

This represents evolved chemical warfare. The birds aren't thinking "snake skin scares away predators." They're following preferences shaped by generations where snake-skin-using birds had higher reproductive success. The mechanism is unconscious; the outcome is strategic.

Temperature regulation drives much nest architecture. Mound-building birds like megapodes create enormous piles of decomposing vegetation that incubate eggs through fermentation heat. Males monitor mound temperature with their mouths, adding or removing material to maintain optimal conditions.

This is active engineering through behavioral feedback. The bird doesn't understand thermodynamics, but it responds to temperature cues with specific actions: too cool, add material; too warm, open vents. The system works through distributed cognition - sensors (mouth), processor (brain responding to stimuli), and actuators (legs and beak) forming a control loop.

In cold climates, nest insulation becomes critical. Birds line nests with feathers, fur, and soft plant material, creating thermal barriers that reduce heat loss. Studies in Arctic environments show properly insulated nests can maintain temperatures 15-20 degrees Celsius above ambient conditions, even during storms.

The insulation isn't random. Birds preferentially select materials with high thermal resistance - downy feathers rather than stiff ones, fine grasses rather than coarse. Again, not conscious material science, but effective nonetheless.

Nest design reflects an evolutionary arms race between birds and predators. Ground-nesting babblers evolved domed nests specifically in response to increased predation risk. Statistical analysis of 155 babbler species shows dome-shaped nests arose when competition for tree sites forced some species to nest on the ground, where predators prowl.

Natural selection produced specific architectural features for defense without any bird consciously engineering protection. Function drives form through differential survival: birds building domes on the ground had more surviving offspring, so dome-building spread.

Hanging nests represent another anti-predator strategy. By suspending nests from branch tips, weavers and orioles make it nearly impossible for climbing predators to access eggs. Some add downward-pointing entrance tubes as additional barriers. Snakes can't easily navigate spiraling tubes that sway with every movement.

Bowerbirds take a different approach. Males construct elaborate structures not for nesting but for courtship displays - architectural presentations decorated with colorful objects to attract females. These aren't functional nests but aesthetic constructions, suggesting birds possess not just engineering capacity but something approaching artistic sensibility.

Nest-building timelines vary dramatically. Some species complete structures in 7-10 days under optimal conditions; others take 2-3 weeks. Mated pairs often work in shifts, with one gathering materials while the other continues assembly.

This division of labor accelerates construction and reduces individual fatigue. It's cooperative engineering, coordinated through behavioral cues rather than verbal communication. How do paired birds know when to switch roles? Through the same embodied intelligence that guides material selection and structural adjustment - observation, response, feedback.

The speed is remarkable considering the complexity. A Baltimore oriole's hanging nest might incorporate hundreds of plant fibers, each woven into a specific position in the overall structure. The bird works without pausing to consult plans because the plan exists in procedural memory - motor sequences that feel right when executed correctly.

What can human engineers learn from birds? Quite a lot, according to researchers studying biomimicry applications.

Bird nests demonstrate that sophisticated structures can emerge from simple rules applied iteratively with environmental feedback. This insight informs robotics, where swarm intelligence uses similar principles - individual robots following basic behaviors that collectively produce complex outcomes.

The entanglement physics discovered in nest construction has applications for architectural scaffolding, disaster relief shelters, and temporary structures. Materials that self-assemble through physical properties rather than adhesives could revolutionize construction in resource-limited settings.

The thermal regulation strategies birds employ - material selection, structure orientation, insulation placement - offer models for energy-efficient building design. Passive climate control through architectural features rather than mechanical systems reduces energy consumption.

Bird nest construction demonstrates that intelligence doesn't require consciousness. Effective problem-solving can emerge from the interaction between evolved biases, environmental feedback, and embodied experience.

Perhaps most profoundly, bird nests demonstrate that intelligence doesn't require consciousness. Effective problem-solving can emerge from the interaction between evolved biases, environmental feedback, and embodied experience. This challenges assumptions underlying artificial intelligence development, suggesting alternative approaches to machine cognition.

Bird nest construction forces us to reconsider what intelligence means. We've traditionally equated intelligence with conscious reasoning, mathematical calculation, and abstract planning. Birds possess none of these, yet they solve engineering problems humans find challenging.

The key lies in recognizing intelligence as distributed rather than centralized. A bird's engineering capacity isn't located solely in its brain - it emerges from the dynamic interaction between neural structure, sensory systems, motor capabilities, and environmental affordances.

This is embodied cognition in action. The bird doesn't represent the nest as an abstract concept, calculate structural requirements, then execute a plan. Instead, building unfolds through reciprocal causation: the bird acts on the environment (places a stick), the environment responds (the stick falls or stays), and the bird adjusts subsequent actions accordingly.

Over generations, evolution shapes these action-perception loops toward effective outcomes. Birds whose embodied problem-solving produced stable, thermally regulated, predator-resistant nests had more surviving offspring. The successful strategies became encoded in neural development, perceptual biases, and motor preferences.

Different bird lineages independently evolved similar architectural solutions to common problems. This convergent evolution reveals that certain designs represent optimal solutions to specific constraints.

Mud construction evolved separately in swallows, thrushes, and other families. Woven structures arose independently in multiple continents. Hanging nests appeared in unrelated species facing similar predation pressures.

These parallel innovations suggest the space of viable architectural solutions is constrained by physics, available materials, and ecological pressures. Within those constraints, evolution repeatedly discovers the same engineering principles.

Humans underwent similar convergent evolution in construction. Cultures worldwide independently developed mud-brick architecture, woven shelters, and suspended platforms. We like to think human innovation stems from conscious intelligence, but perhaps we're also following embodied problem-solving shaped by our evolutionary history and environmental affordances.

As climate change intensifies and resource constraints tighten, bird nest construction offers increasingly relevant lessons for sustainable architecture.

Birds build using locally available, renewable materials. They create structures optimized for specific microclimates without energy-intensive climate control. Their designs withstand environmental stresses through flexibility rather than rigid resistance. And they achieve all this with minimal material waste.

Contemporary architects are already applying these principles. Earth-based construction using natural materials. Passive climate control through strategic design. Modular structures that adapt to changing needs. Biodegradable buildings that return to the environment harmlessly.

The next generation of construction might look less like concrete towers and more like scaled-up bird nests - organic, adaptive, integrated with rather than imposed upon the landscape.

The common tailorbird stitches leaves with spider silk, creating a living nest without understanding sewing, botany, or structural engineering. This isn't a limitation - it's a different kind of intelligence.

By abandoning the requirement for conscious understanding, evolution discovered problem-solving strategies that work reliably across millions of individual birds over millions of years. These strategies encode hard-won engineering knowledge in forms accessible to creatures with small brains and no capacity for abstract reasoning.

Humans build through conscious design, mathematical modeling, and technological tools. Birds build through evolved predispositions, environmental feedback, and procedural memory. Both approaches solve complex problems, but through fundamentally different mechanisms.

Understanding how birds engineer without understanding might be the key to creating more resilient, adaptive, sustainable human structures. Because the birds have been at this far longer than we have, and they've solved problems we're still struggling with.

The nest hanging from your porch, the mud structure under the eaves, the woven sphere swaying in the wind - these aren't just animal behaviors. They're master classes in distributed intelligence, embodied problem-solving, and evolutionary engineering. We'd be wise to pay attention.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

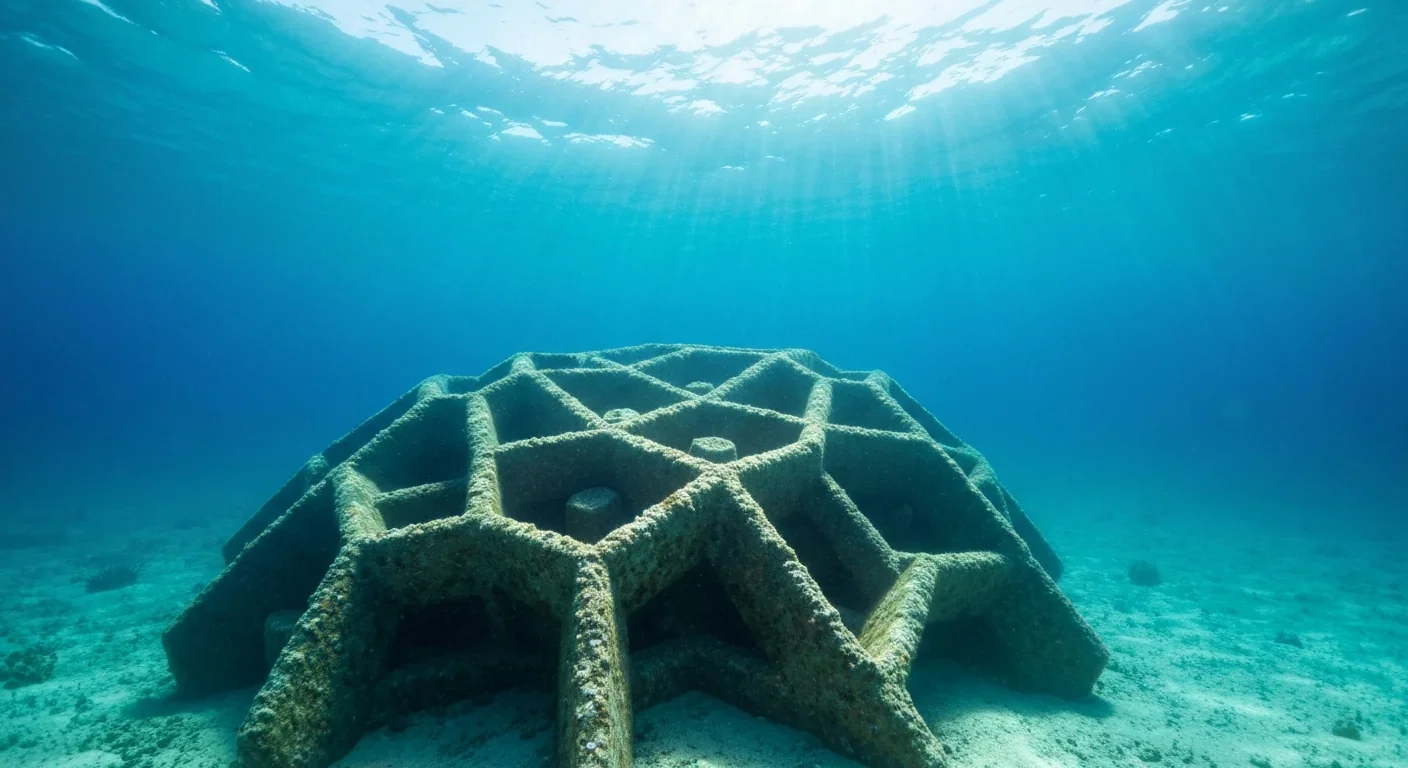

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

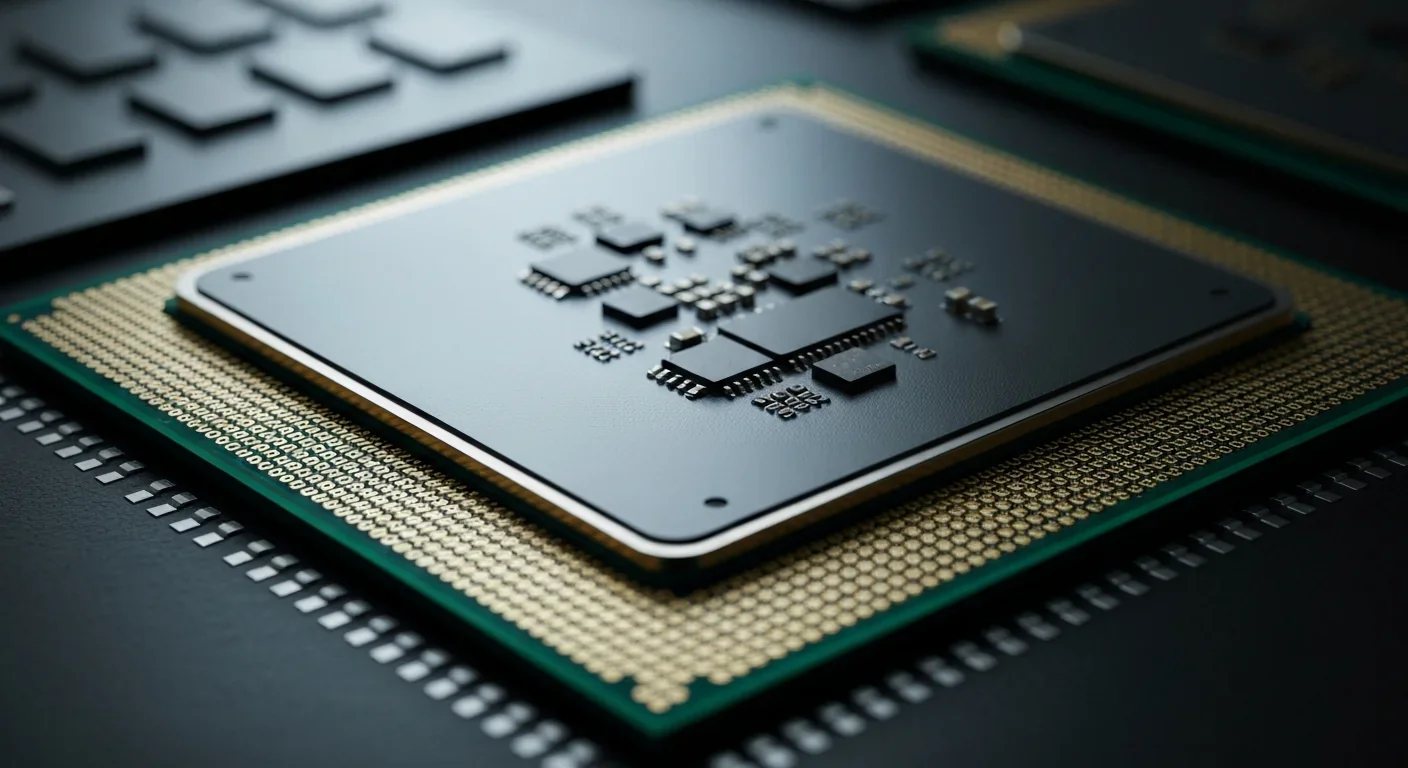

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.