Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Mantis shrimp deliver the fastest punch in nature at 23 m/s, creating cavitation bubbles that implode at sun-surface temperatures and produce light. Their club uses a hyperbolic paraboloid spring for power and a phononic Bouligand structure to survive impacts, inspiring next-generation armor and acoustic metamaterials.

Picture this: a creature the size of your thumb generates an underwater shockwave so powerful it creates temperatures rivaling the sun's surface. Not in some distant alien ocean, but right here on Earth, in coral reefs you might snorkel past on vacation. The mantis shrimp's strike isn't just fast - it's a physics lesson in extreme energy concentration that's rewriting what we thought possible in biological systems.

When a mantis shrimp decides to attack, what happens next seems to violate common sense. Its club-shaped appendage accelerates at 10,400 g - that's over 10,000 times the force of gravity, faster than a .22 caliber bullet leaving the barrel of a gun. The strike reaches speeds up to 23 meters per second (51 mph) in just a few milliseconds, moving so fast the water itself can't get out of the way.

This creates something remarkable: cavitation bubbles. As the club tears through water faster than the liquid can flow around it, the pressure drops below water's vapor point. Tiny bubbles of water vapor form in the club's wake, only to collapse violently microseconds later when the surrounding water rushes back in. That collapse generates temperatures exceeding 4,700°C - nearly as hot as the sun's surface at 5,500°C.

These cavitation bubble collapses produce actual light through sonoluminescence - meaning the mantis shrimp creates miniature underwater stars every time it punches.

Here's the kicker: these bubbles produce light. Not metaphorically, but actual photons you could theoretically see if the flash weren't so brief and faint. This phenomenon, called sonoluminescence, means the mantis shrimp is effectively creating miniature underwater stars every time it punches.

So how does a small crustacean generate this much power? The secret lies in one of nature's most elegant mechanical designs: a saddle-shaped structure in the striking appendage that works like a loaded crossbow.

Biologist Sheila Patek calls it a hyperbolic paraboloid - a curved surface that can store tremendous elastic energy without buckling. The mantis shrimp contracts muscles to bend this biological spring, latching it in place with a specialized mechanism. When the latch releases, all that stored energy explodes forward in less than three milliseconds.

"We know of no other biological example where this saddle-shaped structure is used as a spring."

- Sheila Patek, UC Berkeley Biologist

The geometry isn't random - it's the same shape engineers use in buildings and aerospace structures because it resists deformation while remaining incredibly strong. Evolution discovered this principle millions of years before humans invented architecture.

The force generated can exceed 1,500 Newtons, enough to shatter the shells of crabs, mollusks, and other hard-bodied prey. In aquariums, mantis shrimp have cracked glass tanks during feeding, which is why many facilities refuse to keep them or house them only in extra-thick acrylic.

But here's the paradox that stumped scientists for years: if the mantis shrimp hits hard enough to break glass, why doesn't it shatter its own appendage?

Recent research by Horacio Espinosa and his team revealed an answer as ingenious as the strike itself. The club is built in layers, like a high-tech composite material. The outermost layers contain dense minerals that control how tiny cracks spread from each impact. Go deeper, and you find bundles of chitin fibers arranged in a rotating helix pattern - what scientists call a Bouligand structure.

This helix does something extraordinary: it filters shockwaves by frequency. When the club strikes, it generates acoustic waves that ripple backward through the structure. The herringbone-patterned outer region handles the initial impact, while the corkscrew inner layers act as a phononic shield, selectively absorbing the most damaging high-frequency vibrations before they reach soft tissue.

Evolution built an acoustic metamaterial - a class of artificial substances that didn't exist until the 21st century - into a crustacean's fist millions of years ago.

"The mantis shrimp's dactyl clubs are covered in specially evolved layered patterns which selectively filter out sound," Espinosa explained. "These patterns act like a shield against self-generated shockwaves."

To study this, researchers used laser pulses to generate shockwaves in club cross-sections, then watched how the waves propagated. The Bouligand structure didn't just disperse energy randomly - it channeled and neutralized it with frightening efficiency. Federico Bosia, who analyzed the findings, put it bluntly: "The helix-like structure inside the club appears to be a natural version of engineered materials designed to manipulate the propagation of sound waves."

In other words, evolution built an acoustic metamaterial - a class of artificial substances that didn't exist until the 21st century - into a crustacean's fist millions of years ago.

The direct impact is devastating enough, but the mantis shrimp's prey faces a one-two punch. That cavitation bubble collapsing in the strike's wake delivers a second shockwave that can stun or kill even if the club itself misses.

When a cavitation bubble implodes, it doesn't collapse gently. The surrounding water accelerates inward faster than the speed of sound in air. All that kinetic energy focuses into a microscopic point, compressing the gas inside the bubble so violently that temperatures spike to tens of thousands of degrees Kelvin. Spectral measurements of laboratory-created sonoluminescence show bubble cores reaching at least 20,000 K - hotter than the sun's surface.

The light flash itself lasts only picoseconds and is too faint for the naked eye to detect underwater. But the shockwave from the collapse carries real destructive power. For prey already disoriented by the club's physical blow, this secondary impact can be the difference between escape and becoming dinner.

Interestingly, the mantis shrimp isn't alone in weaponizing cavitation. Pistol shrimp use a similar mechanism, snapping their oversized claw shut so fast it creates a cavitation jet that produces both light and a sharp crack audible above water. Both species evolved to turn fluid dynamics into a hunting tool, exploiting physics that engineers only began to fully understand in the last century.

Why did mantis shrimp evolve such extreme capabilities? The answer lies in their ecological niche and the evolutionary pressures of life in complex coral reef environments.

There are roughly 450 species of mantis shrimp, divided into two main groups: spearers and smashers. Spearers have sharp, barbed appendages for impaling soft-bodied prey like fish. Smashers - including the well-studied peacock mantis shrimp - developed clubs for crushing hard-shelled prey.

In coral reefs, competition for food is intense. Crabs, lobsters, and fish all vie for the same mollusks and crustaceans. Being able to crack open shells that competitors can't access is a massive advantage. But shells evolved tougher in response, driving the need for ever more powerful strikes. This classic evolutionary arms race pushed mantis shrimp biomechanics to their current extreme.

The strike also serves defensive purposes. Mantis shrimp are fiercely territorial, living in burrows they defend aggressively. A single blow can send potential intruders fleeing or kill smaller challengers outright. Given that many species grow only 10-15 centimeters long, this outsized offensive capability levels the playing field against larger predators.

Their strike has even shaped their social behavior. Some species engage in ritualized combat where individuals assess each other's strength through displays and measured strikes before one backs down, avoiding lethal escalation. It's a sophisticated cost-benefit calculation: the strike is metabolically expensive to deploy and risks injury even with protective structures, so settling disputes through signaling when possible is adaptive.

For decades, scientists knew mantis shrimp hit hard, but measuring exactly how hard proved nearly impossible. The strike happens faster than mechanical sensors could track, and the extreme forces broke conventional measurement equipment.

The breakthrough came with high-speed cameras capable of capturing 100,000 frames per second. Researchers could finally watch the strike frame-by-frame, tracking the club's acceleration, measuring the velocity, and observing cavitation bubble formation in real time. Without this technology, much of what we now know about mantis shrimp biomechanics would remain hidden.

More recently, laser-based techniques have allowed scientists to peer inside the club's structure while it's actively dispersing shockwaves. By firing laser pulses at cross-sections of club material, researchers simulate strike conditions and watch stress waves propagate through the layered architecture. This revealed the phononic shielding effect that protects the shrimp from its own power.

"The helix-like structure inside the club appears to be a natural version of engineered materials designed to manipulate the propagation of sound waves."

- Federico Bosia, Physicist

Computer modeling has complemented these experiments. Two-dimensional simulations of wave behavior in the Bouligand structure showed how fiber orientation influences shockwave transmission, helping scientists understand not just what the structure does, but why its specific geometry is so effective.

These advances exemplify how technology and biology inform each other. The tools developed to study mantis shrimp mechanics are now being applied to understand other biological materials, while the lessons learned from the club's structure are inspiring new engineering designs.

When engineers discover a natural structure that solves a problem better than anything humans have designed, they pay attention. The mantis shrimp's club is exactly that kind of structure, and researchers are already exploring applications.

Impact-Resistant Materials: The mineralized outer layers that control crack propagation could inspire next-generation body armor, vehicle armor, and protective equipment. Current ceramic armor plates are effective but brittle - they stop bullets but often shatter in the process. A composite that mimics the mantis shrimp's crack-control strategy could maintain integrity through multiple impacts.

Acoustic Metamaterials: The Bouligand helix structure's ability to filter specific frequencies of mechanical waves has aerospace and defense applications. Imagine aircraft fuselages that passively dampen vibration without added weight, or submarine hulls that reduce sonar signatures by absorbing acoustic energy. The phononic shielding principle is exactly what these applications need.

Energy Storage and Release: The saddle-shaped spring mechanism demonstrates extreme efficiency in storing and rapidly releasing elastic energy. This could inform designs for mechanical actuators, prosthetics that mimic natural motion, or even energy storage devices that need to discharge power quickly.

Lightweight Structural Materials: The club achieves its strength through geometric arrangement of relatively lightweight materials - chitin and calcium carbonate. This aligns perfectly with modern engineering's push toward strong, light composites for applications from aerospace to sports equipment.

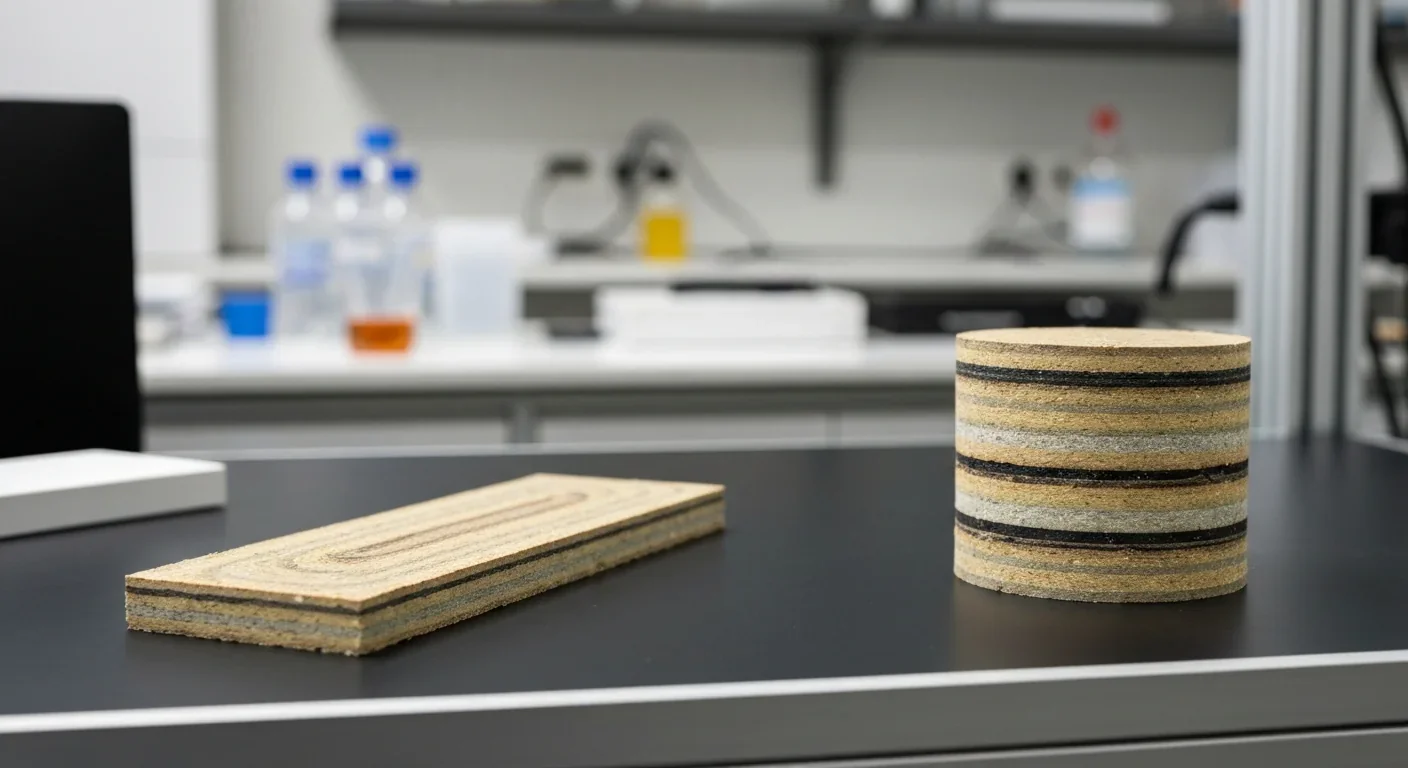

Early prototypes show composites with Bouligand-like layering can absorb up to 20% more impact energy than conventional fiber-reinforced materials of the same weight.

Several research groups are already prototyping mantis-shrimp-inspired materials. Early results show composites with Bouligand-like layering can absorb up to 20% more impact energy than conventional fiber-reinforced materials of the same weight. It's early days, but the potential is clear.

The mantis shrimp's strike is more than a biological curiosity - it's a case study in how evolution solves complex engineering challenges without blueprints or simulations. Millions of years of natural selection refined this system, testing countless variations until arriving at a design that's simultaneously powerful, protective, and practical.

This is the promise of biomimetics: nature has already solved many of the problems we're wrestling with in labs. We just need to look closely enough to understand the solutions and translate them into human applications.

But there's a cautionary note here too. Biomimicry only works when we have functioning ecosystems and species to study. Coral reefs - where mantis shrimp thrive - are under severe pressure from climate change, ocean acidification, and habitat destruction. We're still discovering what these creatures can teach us, yet we risk losing them before we learn all they have to offer.

The mantis shrimp reminds us that the natural world isn't just something to preserve for its own sake (though that's reason enough). It's also an archive of R&D conducted over geological timescales, offering solutions to problems we're only beginning to pose.

The research into mantis shrimp biomechanics sits at the intersection of biology, physics, materials science, and engineering. It's exactly the kind of interdisciplinary work that drives innovation in unexpected directions.

In the near term, we can expect to see mantis-shrimp-inspired materials in specialized applications - military armor, high-performance sports gear, maybe components for spacecraft that need to withstand micrometeorite impacts. These are niche markets, but they're where new materials prove themselves before broader adoption.

Longer term, the principles could scale. If Bouligand structures become manufacturable at reasonable cost, they could appear in everything from construction materials to consumer electronics. Imagine phone screens that don't crack, or car frames that absorb crash energy more effectively while weighing less.

On the scientific front, the mantis shrimp case demonstrates the value of basic research - studying creatures purely to understand how they work, without immediate application in mind. The initial studies of mantis shrimp strikes weren't conducted to develop better armor; they were done because scientists wanted to understand an extraordinary biological phenomenon. The engineering applications came later, as they often do.

This pattern repeats throughout science history. Velcro was inspired by burrs stuck to a dog's fur. Bullet trains got quieter by mimicking kingfisher beaks. Medical adhesives took cues from gecko feet. Each time, curiosity-driven research into nature yielded practical technology.

The mantis shrimp's contribution to this tradition is still unfolding. Every new paper on club microstructure, cavitation dynamics, or shockwave propagation adds another piece to the puzzle. And somewhere, an engineer is reading those papers and thinking, "What if we could build that?"

Perhaps the most astonishing aspect of the mantis shrimp's strike is that it happens millions of times every day, in reefs around the tropical and subtropical world, largely unnoticed by humans. These animals have been deploying sonoluminescence and extreme materials engineering for millions of years while we're only just figuring out how it works.

There's something humbling about that. We pride ourselves on our technological sophistication, but a creature with a brain the size of a grain of rice has been generating sun-surface temperatures and manipulating acoustic waves since before primates climbed down from trees.

It also suggests there's much more to discover. If mantis shrimp can do this, what other physical extremes are playing out in nature that we haven't documented yet? What other evolutionary solutions are waiting to be found in ecosystems we haven't studied closely?

The underwater explosion created by a mantis shrimp's punch - that brief moment of extreme temperature, light, and force - is a reminder that the boundaries of possibility are wider than we imagine. Biology, given enough time and pressure, finds solutions that seem impossible until we see them working.

And now that we've seen them, the question becomes: what are we going to build?

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

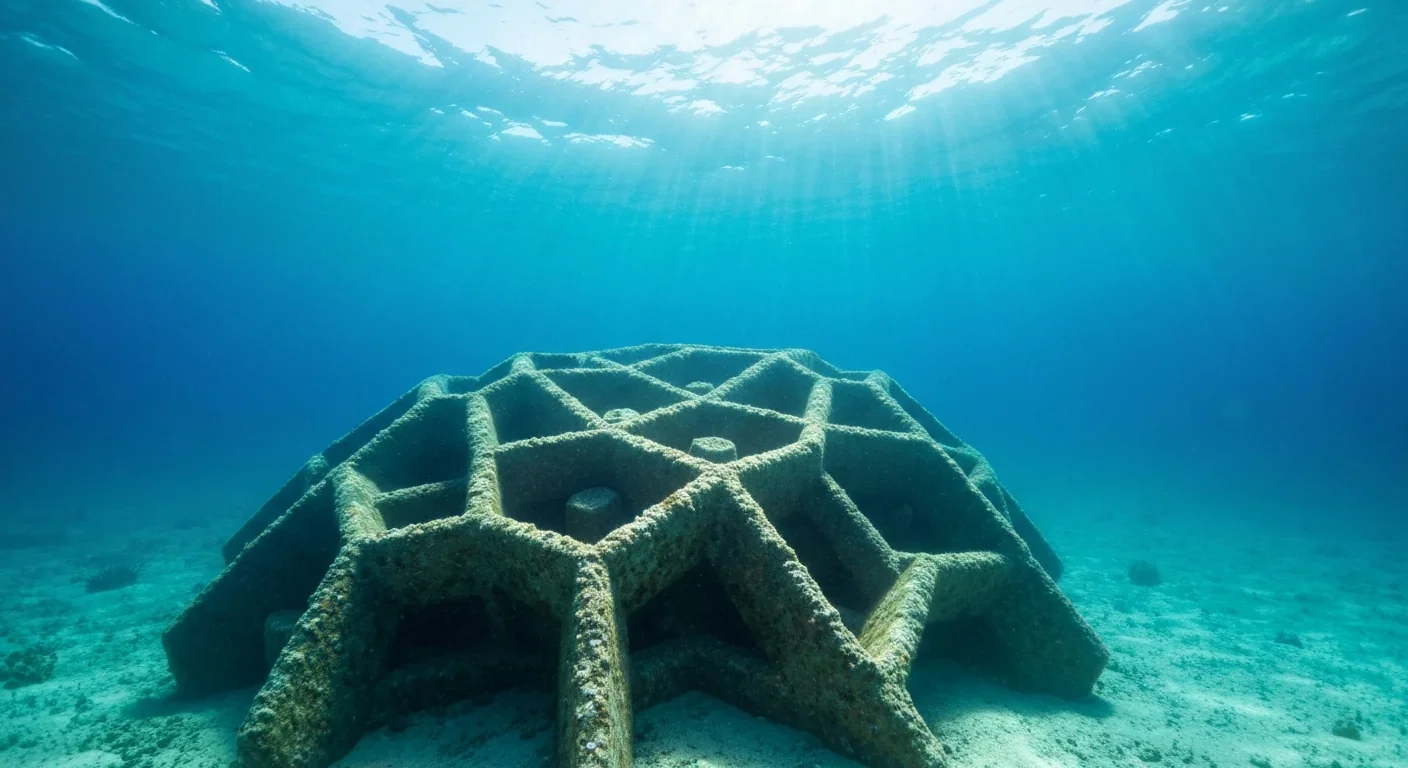

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

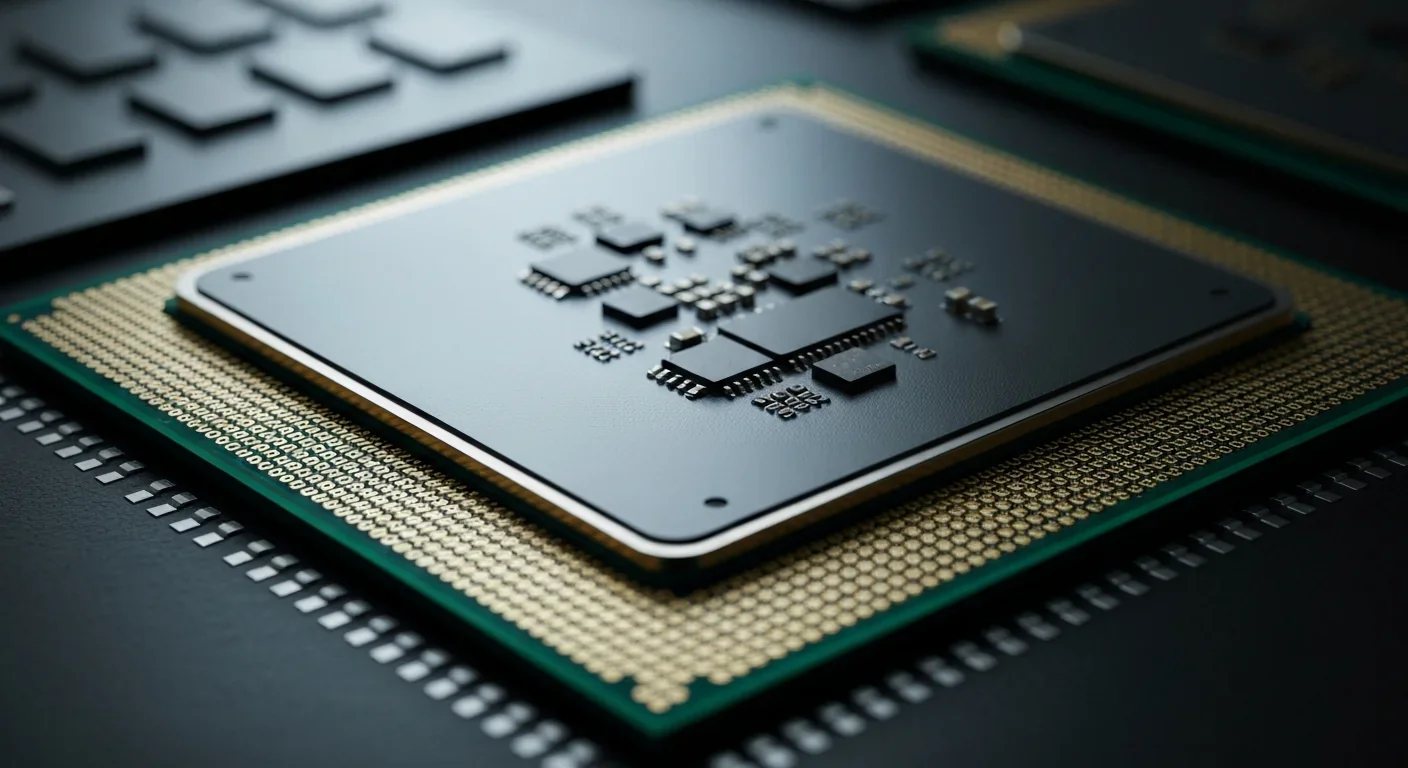

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.