Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Legume plants evolved to capture bacteria and house them in specialized root nodules that convert atmospheric nitrogen into fertilizer. Scientists are now engineering this ancient capability into wheat and corn, which could revolutionize agriculture by eliminating synthetic fertilizer dependence.

Beneath the soil surface, a quiet revolution has been feeding humanity for millennia. Legume plants - from soybeans to peanuts - don't just absorb nutrients from the ground like other crops. They've evolved something far more sophisticated: the ability to capture and domesticate bacteria, transforming their roots into living fertilizer factories. This ancient partnership between plants and microbes produces more nitrogen than all synthetic fertilizers combined, and scientists are now racing to engineer this capability into wheat, rice, and corn. If they succeed, agriculture will never be the same.

The implications ripple far beyond the farm. Synthetic nitrogen fertilizer production consumes 2% of global energy and generates massive greenhouse gas emissions. Meanwhile, agricultural runoff pollutes waterways worldwide. The legume-rhizobia symbiosis offers a glimpse of what agriculture could become: self-fertilizing crops that reduce chemical dependence, cut farming costs, and restore ecological balance. Understanding how this biological technology evolved may be the key to feeding 10 billion people without destroying the planet.

Around 60 million years ago, certain plants in the legume family evolved the ability to do something remarkable: convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia. They didn't develop this capability themselves - they recruited bacteria to do it for them. The partnership works like this: legume roots release chemical signals called flavonoids that attract specific rhizobia bacteria from the soil. When the right bacterial strain arrives, an intricate molecular handshake begins.

The bacteria produce signaling molecules called Nod factors that trigger dramatic changes in the plant's root architecture. Root hairs curl around the bacteria, forming an "infection thread" that allows the microbes to enter plant tissue. The plant then constructs specialized organs called nodules - essentially bacterial housing complexes complete with oxygen regulation systems and nutrient exchange mechanisms. Inside these nodules, rhizobia bacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen gas into ammonia using an enzyme called nitrogenase, one of the most complex molecular machines in biology.

What makes this arrangement extraordinary is its precision. The plant doesn't just allow any bacteria to colonize its roots. It uses a sophisticated recognition system to identify compatible rhizobial strains while rejecting potential pathogens. Recent research revealed that plants can even form nodules spontaneously in the absence of bacteria, suggesting they possess complete control over the architectural program. The bacteria are, in essence, domesticated - transformed from free-living soil microbes into specialized nitrogen-fixing organelles.

A single acre of soybeans can fix 100-300 pounds of nitrogen annually - enough to meet the crop's needs with minimal or no synthetic fertilizer.

The benefits are mutual. Bacteria receive a stable environment and abundant carbon compounds from the plant's photosynthesis. The plant gains access to nitrogen - the essential element for protein synthesis and growth - without depending on scarce soil nutrients. A single acre of soybeans can fix 100-300 pounds of nitrogen annually, enough to meet the crop's needs with minimal or no synthetic fertilizer. This biological innovation has shaped agriculture for thousands of years, though humans only recently understood the microbial partnership underlying it.

Evolution rarely repeats itself exactly, which makes the legume story more remarkable. Root nodulation evolved three separate times within the legume family, suggesting that certain plant lineages possessed a latent capability waiting to be activated. Scientists now believe these plants didn't invent nitrogen-fixing symbiosis from scratch. Instead, they co-opted an even more ancient partnership.

Nearly all land plants form relationships with mycorrhizal fungi, which help them absorb phosphorus and water from soil. This fungal symbiosis dates back more than 400 million years, to when plants first colonized land. The molecular machinery that legumes use to communicate with rhizobia bacteria evolved by repurposing signaling pathways originally developed for mycorrhizal fungi. The plant receptor protein SYMRK, which recognizes bacterial Nod factors, is closely related to proteins that detect fungal signals.

This evolutionary shortcut explains why nodulation arose multiple times. The genetic toolkit already existed - it just needed slight modifications to recognize a new partner. Think of it like adapting a lock to accept a different key rather than designing an entirely new locking mechanism. The ease of this adaptation suggests that other plant families could potentially develop nitrogen-fixing capabilities with relatively modest genetic changes.

Not all nitrogen-fixing partnerships look identical, though. Some tropical trees form nodules with different bacteria called Frankia. Certain wetland plants associate with cyanobacteria. Each partnership evolved independently, yet they all converge on the same basic solution: housing nitrogen-fixing microbes in specialized plant structures. The repeated emergence of this strategy across different plant lineages reveals something profound: biological nitrogen fixation offers such a powerful selective advantage that evolution found multiple paths to achieve it.

Creating a nitrogen-fixing nodule requires solving a fundamental biochemical challenge. Nitrogenase - the bacterial enzyme that converts nitrogen gas into ammonia - is extremely sensitive to oxygen. Even small oxygen concentrations inactivate it permanently. Yet nitrogen fixation requires enormous energy, which bacteria generate through respiration, a process that consumes oxygen. How do nodules protect nitrogenase while simultaneously supplying oxygen for respiration?

The answer involves one of biology's most elegant solutions. Nodule cells produce leghemoglobin, an oxygen-binding protein closely related to the myoglobin in animal muscle. Leghemoglobin creates a buffered oxygen environment, maintaining concentrations high enough to support bacterial respiration but low enough to prevent nitrogenase damage. This protein gives active nodules their characteristic pink color - slice open a healthy soybean nodule and you'll see tissue that resembles raw meat.

"Converting a single nitrogen molecule into two ammonia molecules requires 16 ATP molecules and 8 electrons - more energy than almost any other biological reaction."

- Research on ATP in Plant Metabolism

The energy economics of nitrogen fixation are staggering. Converting a single nitrogen molecule into two ammonia molecules requires 16 ATP molecules and 8 electrons - more energy than almost any other biological reaction. The plant supplies rhizobia with sugars from photosynthesis, which bacteria metabolize to generate this ATP. In return, the plant receives all the fixed nitrogen, which it transports to growing tissues for protein synthesis.

This partnership isn't without conflict, though. The plant must ensure bacteria actually fix nitrogen rather than simply consuming resources. Recent research discovered that nodules produce antimicrobial peptides that allow the plant to control bacterial populations and potentially punish non-cooperative strains. It's a microbial management system that maintains the symbiosis's productivity. The plant monitors bacterial performance and can terminate the arrangement by restricting resources or eliminating underperforming nodules.

The nodule interior resembles a highly organized factory. Outer cortical cells regulate gas exchange. Inner infected cells contain thousands of bacteria, each enclosed in a plant-derived membrane. Vascular tissue connects nodules to the root system, delivering sugars inward and exporting fixed nitrogen outward. This architectural sophistication developed through millions of years of co-evolution between plants and bacteria, each partner shaping the other's biology.

Humans discovered the benefits of legume cultivation long before understanding the microbial mechanism. Ancient farmers noticed that planting beans or peas improved subsequent crop yields - a phenomenon we now recognize as crop rotation. The nitrogen fixed by legumes enriches soil for nitrogen-hungry crops like corn or wheat planted in following seasons. This practice became fundamental to sustainable agriculture worldwide.

Modern estimates suggest biological nitrogen fixation contributes more than 200 million metric tons of nitrogen annually - substantially more than all synthetic fertilizer production. In developing regions where farmers can't afford chemical inputs, legumes remain essential protein sources and soil fertility builders. Subsistence farmers in Africa and Asia rely on beans, peas, and peanuts not just for food but as natural fertilizer for their entire farming system.

The impact extends to livestock agriculture as well. Alfalfa and clover - both nitrogen-fixing legumes - dominate forage production in temperate climates. These crops require minimal nitrogen fertilizer while providing high-protein feed for cattle and other livestock. The nitrogen they fix during growth gets recycled through animal manure, building soil fertility across entire farm systems. A well-managed alfalfa stand can fix 200 pounds of nitrogen per acre annually, year after year, with no synthetic inputs.

But here's where things get complicated. Nitrogen-fixing capability depends on soil containing compatible rhizobia bacteria. Farmers planting legumes in fields lacking the right bacterial strains must inoculate seeds with rhizobia cultures before planting. This commercial inoculant industry - selling packets of beneficial bacteria - now generates hundreds of millions of dollars annually. Researchers work constantly to identify rhizobial strains that perform well across different soil conditions, temperatures, and crop varieties.

Agricultural scientists discovered that plants regulate how many nodules they form through autoregulation - form too many and the energy cost exceeds the nitrogen benefit.

Agricultural scientists also discovered that nodulation has limits. Plants regulate how many nodules they form through a process called autoregulation. Form too many nodules and the energy cost exceeds the nitrogen benefit. This built-in governor prevents plants from over-investing in bacterial partnerships, but it also means there's a ceiling on how much nitrogen a legume crop can fix. Modern research aims to adjust this autoregulation system to increase nitrogen fixation without compromising plant growth.

The grand challenge facing agricultural biotechnology sounds simple: can we transfer nitrogen-fixing capabilities to non-legume crops? Rice, wheat, and corn - the cereals that feed most of humanity - require massive nitrogen inputs. These crops consume more than 100 million metric tons of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer annually. If scientists could engineer cereals to form nodules and host nitrogen-fixing bacteria, the agricultural and environmental benefits would be transformative.

This goal has driven research for decades, and recent breakthroughs suggest it's becoming achievable. In late 2025, researchers announced they'd created wheat plants with nitrogen-fixing capabilities by modifying a single gene. The breakthrough came from understanding SYMRK - the receptor protein that recognizes bacterial Nod factors in legumes. Scientists discovered that adding a small phosphorylation site to this protein transforms it into a molecular switch that can activate nodule formation in non-legume plants.

The modified wheat plants developed nodule-like structures and successfully hosted nitrogen-fixing bacteria. While these early results haven't yet produced field-ready crops, they demonstrate that the genetic gulf between legumes and cereals isn't as vast as once believed. The key molecular machinery for recognizing and hosting nitrogen-fixing bacteria can potentially be transferred with relatively modest genetic modifications.

Another approach involves engineering bacteria rather than plants. Some researchers are creating rhizobia strains that can colonize cereal roots without requiring nodules. These bacteria would live in the rhizosphere - the soil region immediately surrounding roots - and fix nitrogen that plant roots could absorb directly. Early field trials show promise, though the efficiency remains far below what nodule-based systems achieve.

"The genetic gulf between legumes and cereals isn't as vast as once believed. The key molecular machinery for recognizing and hosting nitrogen-fixing bacteria can potentially be transferred with relatively modest genetic modifications."

- UC Davis Wheat Research Team

A more radical vision involves inserting the entire nitrogenase gene complex directly into crop plants, allowing them to fix nitrogen in their own cells without bacterial partners. This faces enormous technical challenges because nitrogenase consists of multiple protein subunits, requires specific metal cofactors, and needs strict oxygen protection. Nevertheless, researchers continue pursuing this approach, achieving incremental progress in engineering functional nitrogenase into plant cells.

The timeline for commercializing nitrogen-fixing cereals remains uncertain. Regulatory pathways for genetically modified crops vary globally, and public acceptance differs across regions. But the research momentum is accelerating. Multiple research groups and agricultural biotech companies now have active programs aimed at bringing self-fertilizing crops to market within the next 10-15 years. The potential economic value - reducing fertilizer dependence for the world's most important food crops - creates powerful incentives to solve remaining technical challenges.

The environmental case for biological nitrogen fixation grows stronger as climate concerns intensify. Synthetic nitrogen fertilizer production via the Haber-Bosch process requires enormous natural gas inputs - about 2% of global energy consumption goes solely to making nitrogen fertilizer. The process releases substantial carbon dioxide, contributing to climate change. Meanwhile, much of the applied fertilizer never reaches crops. Excess nitrogen runs off into waterways, causing algal blooms and dead zones. Some converts to nitrous oxide - a greenhouse gas nearly 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Biological nitrogen fixation offers a carbon-neutral alternative. The energy comes from photosynthesis - captured sunlight that plants convert to sugars and share with bacterial partners. No fossil fuels required. The fixed nitrogen goes directly into plant tissue rather than being applied to soil where it might wash away. While managing nitrogen-fixing systems requires knowledge and attention, the environmental benefits are undeniable.

The agricultural economics shift as well. Nitrogen fertilizer costs represent a major expense for grain farmers, especially when fuel prices spike. Farms growing nitrogen-fixing crops reduce or eliminate this input cost. The nitrogen they leave in soil benefits subsequent crops, creating multi-year returns. For farmers facing tight margins, these economic advantages matter enormously.

But scaling up biological nitrogen fixation faces practical challenges. Legume crops like soybeans and beans generally yield less grain per acre than cereals like corn and wheat. Farmers choosing to plant nitrogen-fixing legumes sacrifice some immediate productivity for long-term soil benefits. Creating market incentives that reward sustainable practices remains an ongoing challenge for agricultural policy.

Climate change itself complicates the picture. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria are sensitive to temperature and soil moisture. As weather patterns shift and extreme events become more common, maintaining productive rhizobial populations may require new approaches. Researchers are identifying drought-tolerant rhizobial strains that continue fixing nitrogen even under water stress. Others are developing coating technologies that protect bacteria from environmental extremes when applied to seeds.

Synthetic nitrogen fertilizer production consumes 2% of global energy and releases substantial carbon dioxide. Biological nitrogen fixation offers a carbon-neutral alternative powered by photosynthesis.

The future of agriculture likely involves multiple nitrogen management strategies. Biological nitrogen fixation will play a larger role, especially in organic and sustainable farming systems. Precision agriculture technologies will help farmers apply synthetic fertilizers more efficiently when needed. And continued research into nitrogen-fixing cereals may eventually transform how humanity grows its staple foods. The goal isn't abandoning all synthetic fertilizers immediately - it's building more diverse, resilient food production systems that don't depend entirely on industrial inputs.

Understanding legume-rhizobia symbiosis opens unexpected perspectives on agriculture's future. For most of farming history, we've treated soil as inert substrate that holds plants upright and stores nutrients. The biological nitrogen fixation story reveals something different: soil as a living system where microbial partnerships determine plant productivity. This shifts how we approach agricultural innovation.

Rather than asking "what crop should we plant?" increasingly relevant questions are: "Which beneficial microbes do we want to cultivate? How do we create soil conditions that support productive plant-microbe relationships? What management practices enhance biological processes rather than replacing them with industrial inputs?" This thinking represents a fundamental shift from chemistry-dependent agriculture toward biology-based farming.

The research tools transforming agriculture increasingly come from molecular biology rather than traditional plant breeding. CRISPR gene editing allows precise modifications to plant recognition systems. Genomic sequencing identifies superior rhizobial strains. Computational modeling helps understand the complex signaling networks coordinating symbiosis. These technologies weren't available even 15 years ago. Their arrival accelerates the pace of agricultural innovation and makes previously impossible goals - like nitrogen-fixing wheat - seem achievable within a generation.

Yet technology alone won't reshape agriculture. Social and economic factors matter just as much. Smallholder farmers in developing regions need access to quality seed and bacterial inoculants. Agricultural extension services must help farmers understand how to manage nitrogen-fixing crops effectively. Markets need to value sustainably produced food appropriately. Policy frameworks should incentivize practices that build soil health rather than degrade it. The biological potential exists; mobilizing it requires coordinated efforts across research, industry, government, and farming communities.

The nitrogen fixation story also carries lessons about innovation itself. Evolution solved the challenge of making nitrogen fertilizer billions of years ago, long before humans existed. The enzyme nitrogenase likely evolved more than 3 billion years ago, predating photosynthesis and complex life. Bacteria have been converting atmospheric nitrogen into biologically usable forms throughout Earth's history. Legumes simply learned to harness this ancient bacterial capability for their own benefit.

Humanity's approach has been different. We invented the Haber-Bosch process barely a century ago, creating synthetic ammonia through high-temperature, high-pressure industrial chemistry. This technology solved immediate food production challenges and supported massive population growth. But it came with costs we're still calculating: energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, water pollution, soil degradation. Now we're returning to biology, asking whether evolution's solutions might prove superior for long-term sustainability.

Try to imagine Midwestern cornfields in 2040. Farmers plant seeds containing nitrogen-fixing bacteria, eliminating fertilizer applications. The bacterial partners draw nitrogen from the air, supplying it directly to growing plants. Farmers save money, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and protect nearby waterways from nutrient runoff. The corn yields match or exceed conventional production, but without the environmental cost.

This vision remains speculative but increasingly plausible. The scientific pieces are falling into place. Researchers understand the molecular signals coordinating plant-bacterial symbiosis. They've identified key genes and proteins controlling nodule formation. They've demonstrated that non-legume plants can be engineered to recognize bacterial partners. The remaining challenges are substantial but not insurmountable.

The timeline to commercialization depends partly on which approach succeeds first. Creating nitrogen-fixing cereals through genetic engineering faces regulatory hurdles but could produce dramatic results. Developing improved bacterial inoculants for existing crops offers a lower-tech path that might arrive sooner. Optimizing legume crops and crop rotation systems can deliver immediate benefits with existing technology. Progress will likely occur across all these fronts simultaneously.

Beyond the technical achievements, this agricultural transformation requires rethinking humanity's relationship with the natural world. For the past century, industrial agriculture has operated on a control-and-dominate philosophy: engineer the biology, eliminate the variables, maximize short-term yields. The nitrogen-fixing future points toward partnership: work with biological systems, enhance natural processes, optimize for long-term sustainability. It's agriculture that accepts complexity rather than simplifying it away.

"The microbial partnerships feeding Earth's ecosystems evolved over vast timescales, refined through billions of reproductive cycles. These systems possess sophistication that human engineering is only beginning to appreciate."

- Evolution of Nitrogenase Enzymes

The microbial partnerships feeding Earth's ecosystems evolved over vast timescales, refined through billions of reproductive cycles. These systems possess sophistication that human engineering is only beginning to appreciate. Learning to work with these biological technologies rather than constantly fighting against them may prove the defining challenge - and opportunity - for 21st-century agriculture. The nitrogen cycle has always been running. We're just learning to tap into it more intelligently.

If someone had told farmers in 1900 that plants could make their own fertilizer with bacterial help, they would have thought it science fiction. Understanding this biological technology changes what seems possible. The symbiosis between legumes and rhizobia has been feeding humanity for millennia, hidden in plain sight beneath the soil. Now that we understand how it works, the question becomes: what else can we learn from evolution's ancient innovations? The answer may determine whether 10 billion people can eat well without exhausting the planet.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

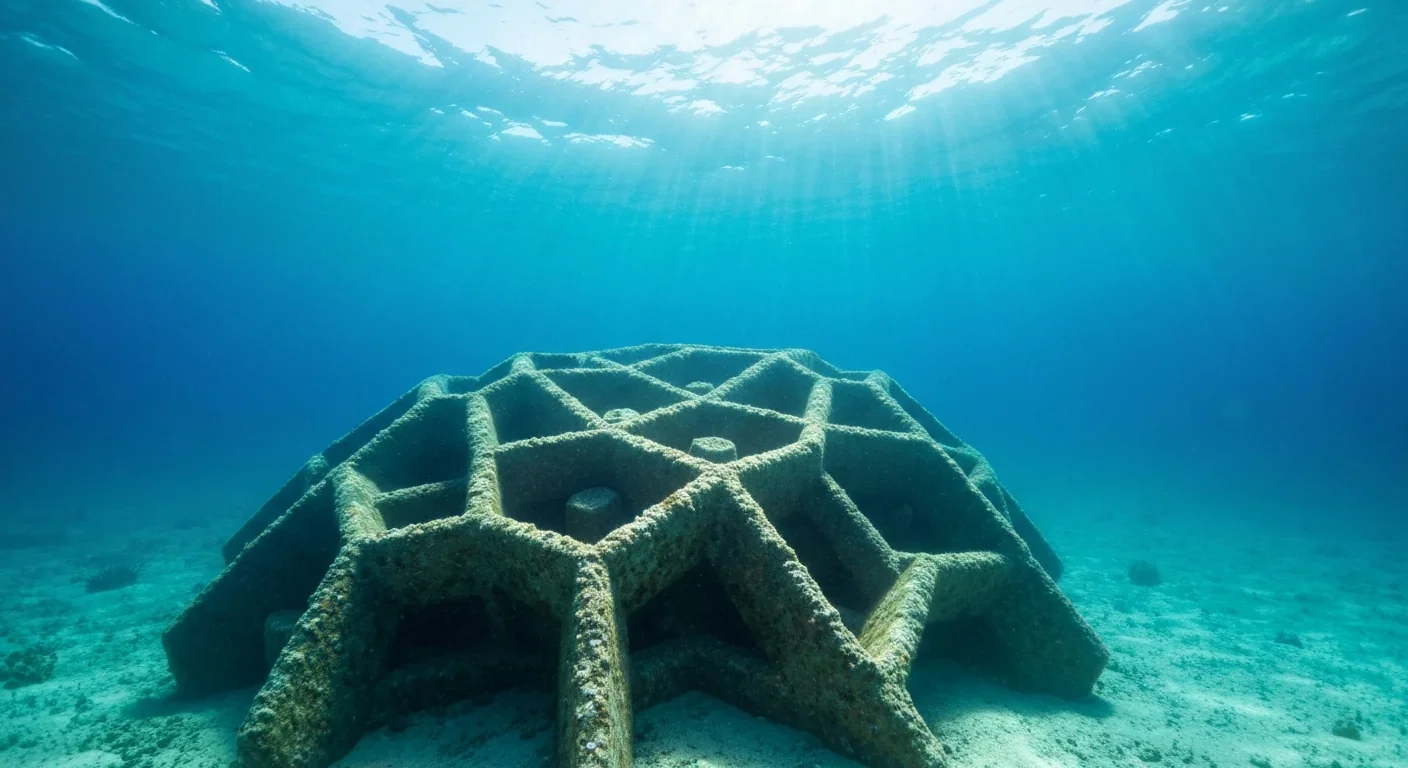

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

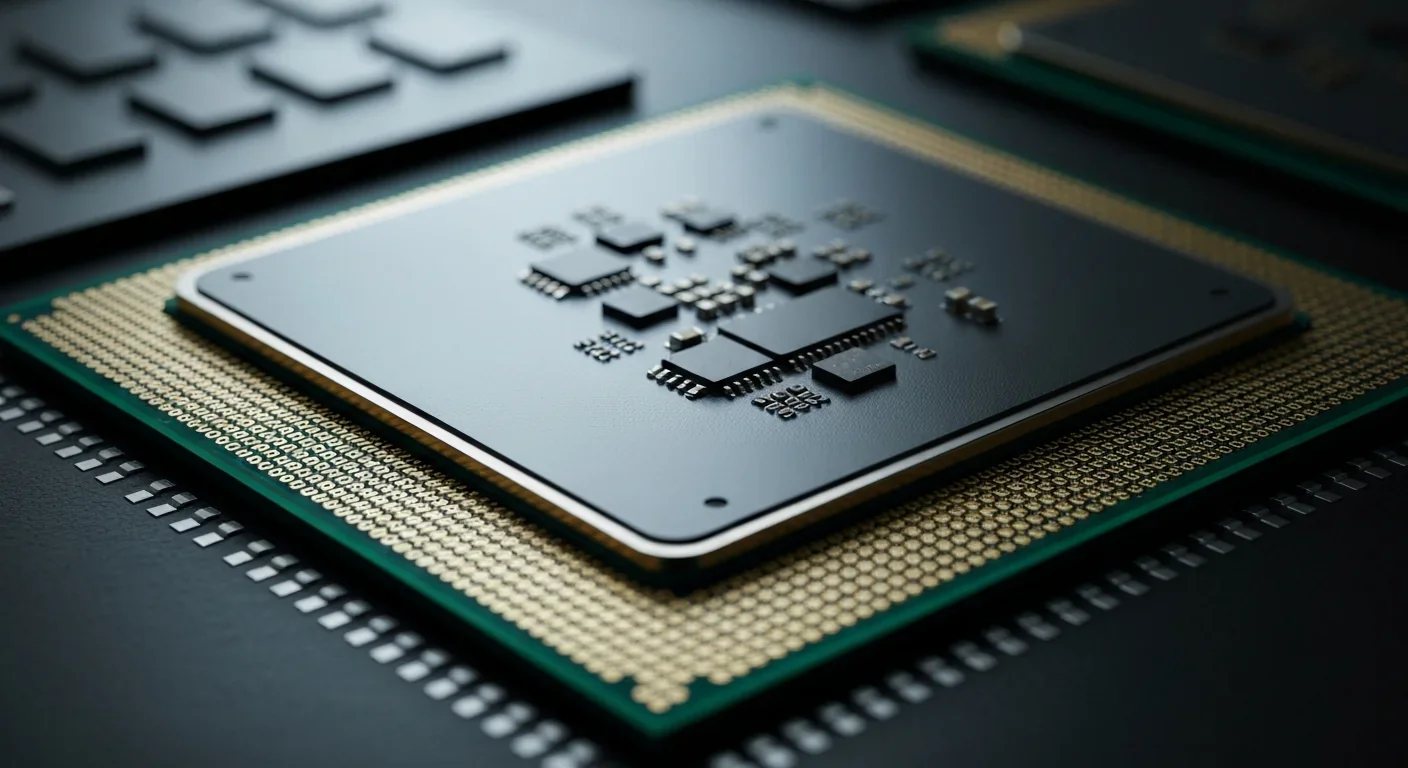

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.