Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Parasitoid wasps weaponized ancient viruses 100 million years ago, integrating viral DNA into their genomes to create biological weapons that hijack caterpillar immune systems, enabling wasp larvae to develop inside living hosts - a strategy now revolutionizing agriculture and biotechnology.

Deep in a wasp's ovaries, an ancient partnership plays out that rewrites our understanding of evolution itself. Over 100 million years ago, parasitic wasps accomplished something that sounds like science fiction: they domesticated viruses, weaving viral DNA into their own genomes and turning these microscopic invaders into precision biological weapons. Today, when a female wasp stings a caterpillar and injects her eggs, she's deploying a molecular arsenal refined across millions of years - one that hijacks the host's immune system so completely that the caterpillar becomes a living nursery for wasp larvae, unable to defend itself even as it's consumed from within.

This extraordinary relationship between wasps and polydnaviruses represents one of nature's most sophisticated examples of biological warfare. Unlike typical viruses that replicate and spread, these domesticated viruses exist solely to serve their wasp masters, produced exclusively in specialized cells of the female wasp's reproductive system and delivered with surgical precision during egg-laying. The implications ripple far beyond entomology - this system is reshaping agriculture, offering insights into gene therapy, and revealing how horizontal gene transfer can drive rapid evolutionary innovation.

The story begins roughly 100 million years ago, when ancestral parasitoid wasps somehow captured a nudivirus - a large DNA virus that normally infects insects. Rather than succumbing to infection, these wasps did something unprecedented: they integrated the entire viral genome into their own chromosomes. This wasn't a temporary arrangement. The viral genes became a permanent part of the wasp's hereditary blueprint, passed down through every generation like eye color or wing shape.

Today's bracoviruses carry genomes that are staggering in complexity. The Cotesia congregata bracovirus genome spans 567,670 base pairs organized into 30 circular DNA segments - one of the largest viral genomes known. Remarkably, 70% of this genetic material consists of introns, the non-coding sequences typical of complex eukaryotic organisms rather than streamlined viruses. This unusual architecture hints at the extent of domestication: these viruses have been so thoroughly integrated into wasp biology that they've adopted features of their host's cellular machinery.

An average female wasp produces over 600 nanograms of viral DNA in each ovary - enough to parasitize hundreds of hosts. Yet she injects just 0.1 nanograms per victim: evolution's precision dosing at work.

The genes dispersed throughout the wasp genome code for viral proteins with evocative names - protein tyrosine phosphatases, ankyrins, cystatins - each evolved to target specific aspects of caterpillar immunity. But here's the crucial twist: these viral genes only activate in one specialized location. Within the calyx cells lining the female wasp's ovaries, the machinery kicks into gear during pupal and adult stages, assembling complete virus particles loaded with their immunosuppressive payload.

An average female produces over 600 nanograms of viral DNA in each ovary - far more than she'll ever need. With each sting, she injects just 0.1 nanograms along with her eggs and a cocktail of venom. It's precision dosing refined by millions of years of evolution.

When polydnavirus particles enter the caterpillar's hemocoel - the blood-filled body cavity - they initiate a carefully choreographed takeover. The virus doesn't replicate inside the host; that chapter of its lifecycle ended when it was domesticated. Instead, viral DNA integrates into the caterpillar's genome and begins expressing up to 200 viral genes, each designed to undermine a different aspect of the host's defenses.

Within 24 hours of oviposition, the caterpillar's immune system collapses. Normally, when a foreign object enters an insect's body, specialized blood cells called hemocytes rush to encapsulate it, smothering the invader in layers of cells and melanin - a process called encapsulation, the insect equivalent of inflammation. But polydnavirus proteins block this response at multiple checkpoints. Viral ankyrins interfere with the production of antimicrobial peptides, the insect's first-line chemical weapons. Protein tyrosine phosphatases disrupt cell signaling pathways that would normally trigger hemocyte activation. Other viral proteins directly inhibit melanization, preventing the caterpillar from isolating parasites.

The timing is crucial. Research on Cotesia congregata shows that hosts lose all ability to encapsulate foreign antigens during the first day after parasitization. This creates a critical window during which wasp eggs hatch and larvae begin feeding. By days 8-10, the caterpillar's hemocyte function partially recovers - it can once again defend against bacterial infections - but by then the wasp larvae have grown large enough to resist encapsulation themselves.

"The biphasic immune suppression creates a time-sensitive window for parasitoid larvae, revealing evolutionary pressure to optimize larval development timing with host immune dynamics."

- Research on Cotesia congregata immune interactions

Recent research reveals even more sophisticated manipulation. A study on Cotesia ruficrus parasitizing fall armyworms discovered that a single viral gene, CrBV3-31, targets the host's lipid metabolism. This gene suppresses LSD1, a protein that regulates lipid droplet formation, causing triglyceride levels in the caterpillar's fat body to spike dramatically. The result? The parasitized caterpillar accumulates fat reserves that the developing wasp larvae consume, essentially turning the host into a customized nutrient factory. Viral gene expression peaks precisely at day 5 post-parasitism, synchronized with the larvae's maximum nutrient demands.

And the manipulation extends beyond immunity and metabolism. Polydnaviruses interfere with the caterpillar's hormonal pathways, particularly the prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH) system that triggers metamorphosis. Parasitized caterpillars can't pupate - they remain stuck in larval form, continuing to feed and grow even as wasp larvae consume them from inside. Meanwhile, giant cells called teratocytes, derived from the wasp egg's outer membrane, secrete additional hormones that work in concert with viral immune suppression to arrest the host's development.

The wasp-virus partnership isn't just ancient - it's evolved independently multiple times. Two major wasp families, Braconidae and Ichneumonidae, each domesticated viruses separately. Braconids captured nudiviruses to create bracoviruses, while ichneumonids integrated a completely different lineage to produce ichnoviruses. Despite their distinct origins, both types of polydnaviruses converge on similar strategies: genome integration, ovary-specific replication, and multi-targeted immune suppression.

This convergent evolution suggests that viral domestication offers such a profound advantage that natural selection discovered it twice. And the partnership is truly obligate - modern parasitoid wasps cannot successfully parasitize hosts without their viral symbionts. All individuals carry the integrated viral genes; it's as fundamental to their biology as venom or wings.

But caterpillars aren't passive victims. Some species have evolved behavioral countermeasures - they construct silk webs around parasitoid pupae when the wasps finally emerge from the caterpillar's body to pupate externally, protecting the pupae from hyperparasitoids (parasites of parasites). This bodyguard behavior, induced by manipulation of the caterpillar's nervous system, ensures the wasps survive to adulthood even after the host dies.

More remarkably, the viral genes don't always stay confined to their targets. Research published in PLOS Genetics revealed that many butterfly and moth species - including iconic species like the monarch butterfly - carry fragments of bracovirus DNA permanently integrated into their genomes. These aren't recent acquisitions. The genes have been there for millions of years, inherited through countless generations. And they're not genetic junk: experiments show that butterflies with these wasp-derived genes show increased resistance to baculoviruses, deadly pathogens that plague lepidopteran populations.

Monarch butterflies and other lepidopterans carry fragments of wasp-virus DNA in their genomes - naturally occurring "GMOs" that challenge our understanding of genetic boundaries and evolution itself.

This represents horizontal gene transfer on a grand scale - genetic material jumping not just between individuals, but across kingdoms of life, from virus to wasp to butterfly, each time conferring new capabilities. It challenges our tidy categories of "self" and "other" at the genomic level.

For farmers battling crop pests, parasitoid wasps represent a dream come true: self-replicating, highly specific biological control agents that target pests without harming beneficial insects or requiring chemical inputs. Since the 1920s, wasps like Encarsia formosa have been deployed in greenhouses worldwide to control whiteflies, and the technology has only gotten more sophisticated.

Cotesia ruficrus, the species studied for its lipid-manipulating virus, has emerged as a key biological control agent against the invasive fall armyworm in China, a devastating pest that causes billions in agricultural losses. Unlike broad-spectrum insecticides that wipe out entire insect communities, these wasps zero in on specific caterpillar species, leaving pollinators, predators, and other non-targets completely unharmed.

The beauty of the system is its elegance. Release parasitoid wasps into infested fields, and they do the rest - seeking out caterpillars, assessing their suitability as hosts, and deploying their viral weapons with microscopic precision. Each female can parasitize dozens of hosts during her lifetime, and her offspring continue the work. Unlike chemical pesticides that degrade and require reapplication, biocontrol populations establish themselves and persist as long as pests remain.

Researchers at the University of Georgia are now investigating how wasps activate their viral genes in response to hormonal cues during metamorphosis, seeking to optimize mass-rearing programs for biocontrol. Understanding the molecular triggers could allow production facilities to time wasp releases for maximum effectiveness, or even engineer wasps with enhanced virulence against emerging pest species.

The applications extend far beyond pest management. Polydnaviruses are proving to be treasure troves for biotechnology research, offering ready-made tools for immune manipulation that evolution spent 100 million years perfecting.

Consider gene therapy. One of the biggest challenges in delivering therapeutic genes to patients is evading the immune system long enough for the treatment to work. Polydnavirus proteins that suppress hemocyte activation or block antimicrobial peptide production could potentially be adapted as immunosuppressive agents, creating windows for gene therapy vectors to integrate without triggering rejection.

The viral genes that manipulate host lipid metabolism are drawing attention from metabolic disease researchers. If a single viral protein can reliably increase triglyceride accumulation in insect fat bodies, understanding that mechanism might reveal new targets for treating metabolic disorders or optimizing livestock feed conversion.

"Individual PDV genes can target discrete host metabolic processes, suggesting that viral domestication allows parasitoids to fine-tune host physiology beyond immune suppression."

- Study on Cotesia ruficrus bracovirus lipid manipulation

And the horizontal gene transfer findings have implications for understanding immunity across all animals. If butterflies can incorporate viral defense genes and gain resistance to new pathogens, could similar transfers have shaped mammalian immune evolution? Fragments of ancient viral DNA make up roughly 8% of the human genome - are any of them functional, and if so, what do they do?

Researchers have even demonstrated experimental horizontal gene transfer of phage-derived toxin genes to fruit flies, conferring innate immunity to parasitoids. This proof of concept suggests that synthetic gene transfer could be engineered to protect agricultural species or manipulate ecological interactions in controlled ways.

As biotechnology races to harness these systems, thorny questions emerge. If we can edit crop genomes to include parasitoid-resistance genes derived from viruses, should we? The butterflies carrying wasp-virus genes are "naturally occurring GMOs," proof that horizontal gene transfer happens constantly in nature. But should that give us license to accelerate the process?

Biocontrol releases raise their own concerns. Introduced parasitoid species have occasionally established beyond their intended ranges or switched to non-target hosts. The wasps might be precise now, but evolution is ongoing - what happens if they adapt to attack beneficial insects or native species?

There's also the question of suffering. Caterpillars parasitized by wasps undergo a prolonged death, kept alive and developmentally arrested while larvae feed on their tissues. For subsistence farmers desperate to save crops from pest devastation, that's a worthwhile trade-off. For others, it raises questions about the ethics of biological control in a world where we're increasingly sensitive to animal welfare.

And if we engineer "super-wasps" with enhanced viruses or modified host ranges, are we crossing a line from harnessing nature to fundamentally rewriting it? The genie is already partly out of the bottle - CRISPR and synthetic biology give us tools our ancestors never imagined. The polydnavirus system shows us that nature has been doing genetic engineering for eons, swapping genes between species and kingdoms without regard for the boundaries we draw. But that doesn't automatically mean we should follow suit without careful deliberation.

Within the next decade, the food on your plate will likely have been protected, at least in part, by parasitoid wasps and their viral weapons. Organic and conventional farmers alike are embracing biocontrol as pesticide resistance spreads and consumer demand for chemical-free produce grows. The wasps work quietly, invisibly, in fields and orchards around the world.

If current research trends continue, you might also benefit medically. Immunosuppressive drugs derived from viral proteins could reduce organ transplant rejection or treat autoimmune diseases with fewer side effects than current therapies. Gene therapies using polydnavirus-inspired delivery mechanisms might cure genetic diseases that are currently untreatable.

For parents and educators, the wasp-virus story offers a powerful teaching moment. It reveals evolution not as a stately march of progress, but as an endless, improvised arms race where survival goes to the creative and adaptable. It shows that the boundaries between species are more porous than we assumed, that cooperation between organisms can be as powerful as competition, and that today's enemy can become tomorrow's indispensable ally.

Looking ahead, polydnavirus research is entering an exciting phase. Whole-genome sequencing projects for dozens of parasitoid species are revealing the full extent of viral diversity and the genetic innovations that different wasp lineages have evolved. Comparative genomics will show which viral genes are universal - likely the core immune-suppression toolkit - and which are species-specific adaptations.

Synthetic biology approaches could create entirely novel polydnaviruses, mixing and matching genes from different wasp species to create custom immune-suppression profiles. Imagine engineering a biocontrol wasp capable of parasitizing multiple pest species, or one whose virus specifically targets invasive species while sparing native relatives.

Synthetic biology could soon enable custom-designed polydnaviruses that mix genes from different wasp species - biological weapons tailored for specific agricultural challenges or ecological restoration projects.

Climate change is also reshaping the landscape. As temperature zones shift and pest ranges expand, parasitoid wasps and their viruses will be tested in new ecological contexts. Species that historically never encountered certain wasps may suddenly face parasitism pressure, while traditional host-parasitoid relationships may be disrupted. Monitoring these shifts and adaptively managing biocontrol programs will become increasingly important.

The molecular mechanisms are also yielding surprises. The discovery that individual viral genes can target discrete metabolic pathways, like the lipid droplet regulation controlled by CrBV3-31, suggests that polydnaviruses are far more sophisticated than early research suggested. Each gene might be a precision tool for manipulating a specific aspect of host physiology, and we're only beginning to catalog the full toolkit.

Perhaps the deepest lesson from polydnaviruses is philosophical. For decades, biology taught that evolution proceeds primarily through vertical gene transfer - parent to offspring, generation by generation. The modern synthesis of genetics and natural selection was built on that foundation. But horizontal gene transfer, once thought rare, is now recognized as a major evolutionary force.

Polydnaviruses embody this revisionist view. They're not just wasps, not just viruses, but chimeric entities that blur definitions. The viral genes in butterfly genomes further scramble the picture. Where does the wasp end and the virus begin? Where does the virus end and the butterfly begin? The answer is that these boundaries are artifacts of human classification, not fundamental features of biology.

This recognition has implications for how we think about all life. If genes flow horizontally across vast evolutionary distances, then the tree of life is less a tree and more a web, with branches reconnecting in unexpected places. Our own genomes are mosaics of human, viral, and bacterial sequences acquired over millions of years. We are all, to some extent, chimeras.

The wasp-virus partnership shows that evolution is wildly creative, capable of solutions that no human designer would conceive. It's a reminder that nature's complexity exceeds our models, and that humility is warranted as we venture into biotechnology and ecological engineering. The wasps didn't plan to domesticate viruses; natural selection discovered that solution through countless failed experiments we'll never know about.

As we stand on the brink of our own era of biological engineering, the polydnavirus story offers both inspiration and caution. Inspiration, because it shows what's possible when biological systems integrate and innovate. Caution, because evolution operates on timescales we can barely fathom, testing solutions across millions of generations before settling on winners. Our interventions will be faster, but are they wiser?

The tiny wasp injecting her eggs into a caterpillar contains multitudes - viral genes, bacterial symbionts, her own genome shaped by parasitism - all working in concert. She's a reminder that nature's most powerful innovations often come from cooperation between unlikely partners, and that the future belongs to those who can forge new alliances in a changing world.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

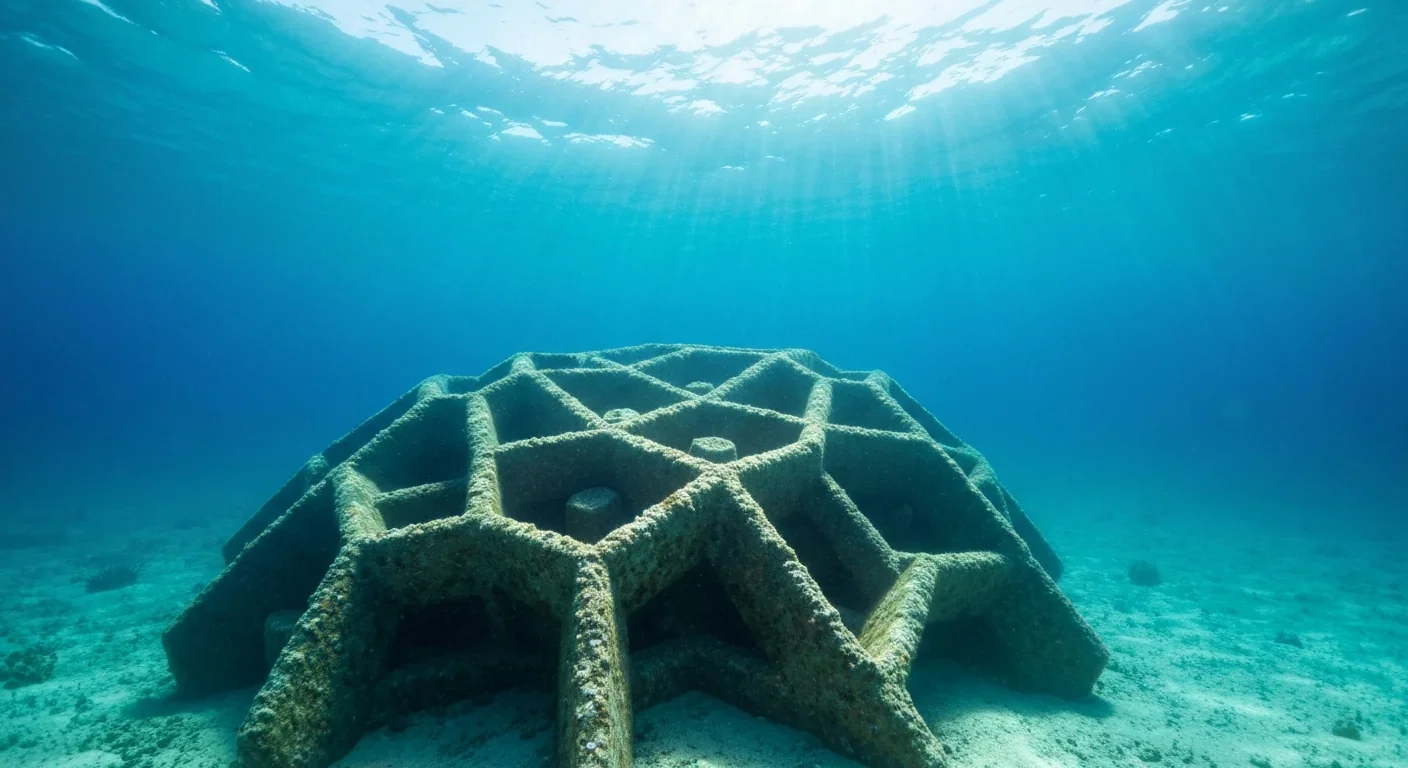

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

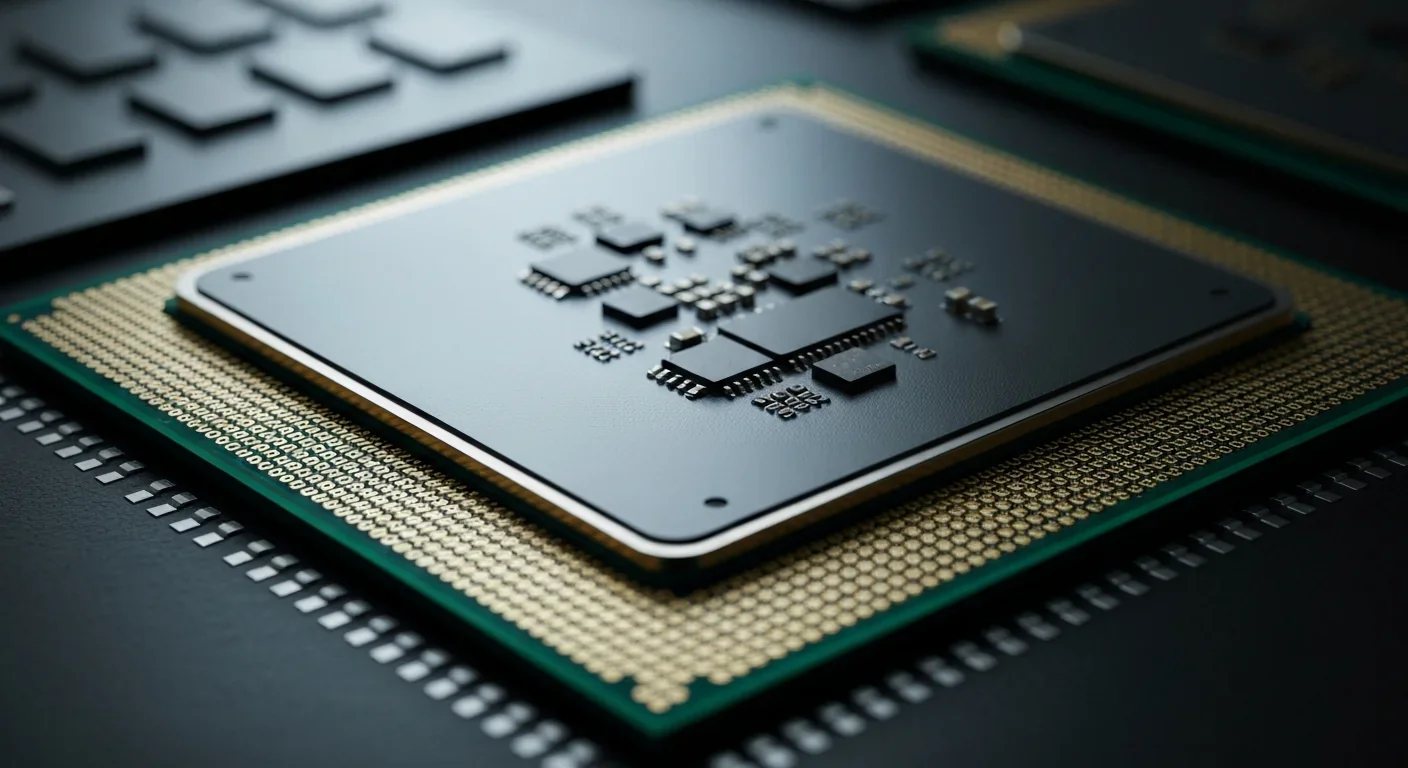

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.