Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Long before humans discovered farming, another species was already perfecting sustainable agriculture. Leafcutter ants have been cultivating crops for roughly 50 million years, developing a sophisticated system that puts many human agricultural practices to shame. These tiny farmers don't just collect food - they grow it, manage it, and protect it with techniques that researchers are only now beginning to understand and apply to modern challenges.

The story of leafcutter ant agriculture stretches back to a time when primates were just emerging in Earth's evolutionary timeline. Around 56.9 million years ago, the fungus genus Escovopsis first appeared, though it wouldn't interact with modern mutualistic ants until roughly 38 million years later. But the real agricultural breakthrough came when leafcutter ants began cultivating Leucoagaricus gongylophorus, a fungus species that would become completely dependent on its ant farmers.

This wasn't a quick process. The ants fully domesticated their fungal partner 15 million years ago, after 30 million years of gradual coevolution. The result? A farming system so refined that the cultivated fungus no longer produces spores - it exists solely within ant colonies, propagated by the farmers themselves.

Think about that for a moment. These ants achieved something humans are still struggling with: they created a perfectly sustainable, closed-loop agricultural system that has thrived for millennia without depleting resources or requiring external inputs beyond fresh leaves.

Walk into a leafcutter ant colony and you'll witness organizational complexity that would make any human corporation jealous. These aren't simple insects mindlessly following instinct - they're participants in a sophisticated division of labor that rivals the most efficient human operations.

The colony operates through distinct castes, each specialized for specific agricultural tasks. Minims, the smallest workers, tend the growing brood and meticulously care for the fungus gardens, grooming the crop and removing any contaminants. Minors handle most of the leaf processing, cutting vegetation into smaller pieces suitable for fungus cultivation. Mediae workers are the primary foragers, venturing out to harvest fresh leaves - and here's where it gets impressive: these workers can cut and carry leaf pieces that weigh up to 50 times their own body weight. That's equivalent to a 150-pound human carrying around a 7,500-pound load.

Majors serve as the colony's defenders, protecting the foraging trails and the nest itself from predators and rival colonies. But there's another critical caste that often goes unnoticed: the waste-heap workers, specialists who handle one of the most sophisticated aspects of ant agriculture - sanitation.

Each caste isn't born knowing its role; body size determines function, and this specialized morphology has evolved over millions of years to maximize efficiency. It's biomechanical design perfected through natural selection.

A mature colony can house up to 3.55 million individuals, all working in synchronized harmony - a living example of how specialized roles and cooperation create systems that transcend individual capabilities.

One of the most remarkable aspects of leafcutter ant agriculture is the communication between farmer and crop. Ants don't randomly grab any leaf they encounter. They're sensitive enough to detect chemical signals from their cultivated fungus, apparently receiving feedback about which plant materials work best for cultivation.

This chemical dialogue represents a level of agricultural sophistication that humans are only beginning to replicate with modern sensor technology. The ants essentially have a real-time monitoring system that tells them when their crop is thriving or struggling, allowing them to adjust their harvesting accordingly.

The fungus itself has evolved to serve the colony's nutritional needs. It produces specialized structures called gongylidia - nutrient-rich swellings that serve as the primary food source for the ants. In return, the ants provide the fungus with fresh substrate, protection from competitors, and ideal growing conditions. This mutualistic relationship has become so intertwined that neither species can survive without the other - a true obligate symbiosis forged over millions of years.

Starting a farm from scratch is challenging for any species, but leafcutter ants have developed an elegant solution. When a new queen leaves her parent colony for her mating flight, she doesn't travel empty-handed. She carries a small piece of fungus garden in her infrabuccal pocket - a specialized storage space within her mouth.

After mating and finding a suitable location, the queen begins her agricultural venture with this tiny starter culture. She nurtures it carefully, fertilizing it with her own feces until the first workers emerge to take over cultivation duties. This intergenerational transfer of agricultural knowledge - or rather, the living crop itself - ensures continuity across generations. It's a system that has worked flawlessly for 50 million years.

Compare this to human agriculture, where the loss of seed varieties and traditional farming knowledge represents a genuine crisis. The ants never face this problem because the queen literally carries the means of production with her.

"These fungi are still poorly understood from physiological and ecological points of view. Therefore, it's premature to treat them all as parasites."

- Quimi Vidaurre Montoya, Researcher

Any farmer knows that crop diseases can devastate yields, and leafcutter ants face this challenge too. The parasitic fungus Escovopsis has long been considered the primary threat to ant fungus gardens. But recent research reveals a more nuanced picture.

According to researcher Quimi Vidaurre Montoya, treating all Escovopsis strains as parasites is premature. The study analyzed 309 strains from eight countries and found that these fungi might actually play varied ecological roles, with some potentially acting as opportunistic detritivores rather than true pathogens.

What's even more fascinating is how ants deal with potential threats. Rather than relying heavily on chemical antibiotics, colonies employ what scientists call a social immune system. Workers actively remove potentially virulent fungi and contaminated material, discarding it far from the gardens. This behavioral defense reduces the need for aggressive antibiotic production - a lesson that could inform human approaches to disease management in agriculture.

Montoya notes an intriguing point: "If it were a specialized virulent host, as part of the literature assumes, it would destroy the system regardless of whether it was in equilibrium or not." The fact that catastrophic outbreaks rarely occur suggests the ant-fungus-Escovopsis system exists in a complex balance that researchers are still working to understand.

The ants do produce some antimicrobial compounds through symbiotic bacteria living on their bodies, but physical removal and waste management form the primary defense. It's integrated pest management that works.

Perhaps nowhere is the sophistication of leafcutter ant agriculture more evident than in their waste management systems. A colony might house between 1 to 3.55 million individuals, all producing waste that could quickly contaminate the fungus gardens if not properly handled.

The solution? Dedicated external waste heaps maintained by specialized workers who build, organize, and monitor these refuse sites. These aren't random dumps - they're carefully managed facilities located at safe distances from active fungus gardens. The waste-heap workers themselves often remain segregated from the rest of the colony, preventing any potential pathogens from spreading to the agricultural areas.

This spatial segregation of waste represents a sophisticated understanding of hygiene principles that human societies took millennia to develop. The system works so well that researchers describe it as hygienic spatial segregation not commonly seen in other ant species.

What happens to all that organic waste? Rather than becoming a liability, the external heaps support their own ecosystems, with decomposer organisms breaking down the material. Some researchers suggest that Escovopsis itself might feed on this debris, playing a role in the colony's nutrient cycling rather than simply acting as a parasite.

Leafcutter ant waste management involves dedicated worker castes that maintain external refuse heaps at safe distances from fungus gardens - a level of sanitation planning that rivals modern municipal systems.

To truly appreciate leafcutter ant farming, you need to understand the sheer scale of their operations. A mature colony's central mound can grow to more than 30 meters across, with smaller radiating mounds extending out to an 80-meter radius. The underground structure can cover 30 to 600 square meters and extend up to 50 feet deep.

Within this subterranean complex lie the fungus gardens - chambers specifically designed to maintain optimal growing conditions. While we don't have complete data on how precisely ants control temperature and humidity, observations suggest they manage these factors through strategic tunnel design and worker behavior, creating microenvironments suited to fungal cultivation.

The biomass these colonies process is staggering. Though exact annual figures vary by location and species, a single large colony can strip entire trees of foliage, processing tons of vegetation through their agricultural system each year. This makes leafcutter ants among the dominant herbivores in neotropical forests, playing a crucial role in nutrient cycling and forest dynamics.

Scientists are increasingly looking to leafcutter ants for insights into sustainable agriculture and biotechnology. Recent research from the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory used advanced metabolome-informed proteome imaging to map the fungal gardens at the molecular level, revealing exactly where and how plant material gets broken down.

The study found that resident bacteria in the gardens produce amino acids and vitamins that support the overall ecosystem - essentially a nitrogen-fixing operation that enriches the growing medium. This discovery has direct applications for biofuel production, as researchers work to understand how to efficiently break down lignocellulose in plant material.

Lead researcher Kristin Burnum-Johnson noted the breakthrough in mapping these microhabitat chemistry hotspots. By identifying where specific enzymes and metabolites concentrate, scientists can potentially design more efficient industrial processes for converting plant waste into usable products.

But the lessons go beyond biochemistry. The ants demonstrate principles that regenerative agriculture advocates have been promoting:

Closed-loop nutrient cycling: Nothing goes to waste in ant colonies. Organic matter moves from forest to fungus garden to ant biomass to waste heap, with each stage supporting the next.

Minimal external inputs: Beyond harvesting fresh leaves, the system is self-sustaining. The ants don't need fertilizers, pesticides, or irrigation systems - they've engineered a crop and cultivation method perfectly matched to their needs.

Disease management through diversity and hygiene: Rather than monoculture vulnerability, the ants maintain system health through active sanitation, physical removal of threats, and beneficial microbe partnerships.

Specialized labor increasing efficiency: Division of labor based on physical traits maximizes productivity, with each caste optimized for specific tasks.

Long-term sustainability: Fifty million years of continuous operation speaks for itself. This isn't extractive agriculture that depletes soil and requires new land - it's regenerative and self-perpetuating.

The relationship between leafcutter ants, their fungal crop, and associated microbes represents one of nature's most complex coevolutionary systems. Over millions of years, each participant has shaped the others' evolution, creating increasingly specialized adaptations.

The fungus evolved to produce gongylidia specifically suited to ant nutrition. The ants evolved anatomical features like the infrabuccal pocket for transporting fungus, as well as the behavioral sophistication to maintain gardens. Even Escovopsis, once thought to be purely parasitic, may have evolved into a more complex ecological role within the system.

Researcher Montoya's team found that Escovopsis has developed physical and biological changes over evolutionary time, with vesicle morphology shifting from globular to cylindrical, increasing reproductive output. These adaptations likely help it survive within ant nests, but perhaps not solely as a destructive parasite.

This dynamic equilibrium offers a profound lesson: agricultural systems work best when all participants adapt together over time, creating relationships of mutual benefit or at least manageable coexistence. Human agriculture, by contrast, often introduces new crops to new environments without allowing time for such adjustment, leading to pest and disease problems that require increasingly intensive interventions.

"If it were a specialized virulent host, as part of the literature assumes, it would destroy the system regardless of whether it was in equilibrium or not."

- Quimi Vidaurre Montoya, on Escovopsis research

As we face agricultural challenges from climate change, soil degradation, and antibiotic resistance, leafcutter ant farming offers a proven alternative model. Several areas show particular promise for biomimicry:

Waste-to-resource systems: The ants' complete recycling of organic matter could inspire industrial composting facilities and waste processing plants that turn agricultural byproducts into valuable inputs.

Microbial community engineering: Understanding how ants maintain beneficial bacterial populations could improve our use of probiotics in crop production and reduce reliance on synthetic fertilizers.

Behavioral disease management: The social immune system concept could translate to human agricultural practices, emphasizing rapid detection and removal of infected plants rather than prophylactic chemical applications.

Decentralized food production: The ants grow food where they live, minimizing transportation and storage needs. Urban agriculture initiatives are beginning to adopt similar principles.

Crop domestication insights: Studying how ants fully domesticated their fungus might inform efforts to develop new crop varieties or bring wild species into cultivation.

The PNNL research team working on biofuel applications represents just the beginning. As our molecular imaging and genetic analysis tools improve, we'll likely uncover even more mechanisms worth emulating.

Here's what strikes me most about leafcutter ant agriculture: it works. Not just in controlled laboratory settings or with constant human intervention, but in the real world, across diverse environments, for millions of years.

These colonies face competition, predation, disease, and environmental variation, yet their agricultural system persists. They've solved problems that still plague human farming - pest resistance, soil fertility, sustainable intensification, waste management - through evolutionary refinement rather than technological quick fixes.

The ants aren't smarter than us in the conventional sense. They're not consciously designing agricultural systems or running experiments. But they're operating with tested solutions that have survived the ultimate quality control: natural selection.

When a queen ant carries her small fungus sample into the world to start a new colony, she's participating in an unbroken chain stretching back 50 million years. Every colony alive today represents a success story, descended from countless generations of colonies that grew their crops, managed their waste, defended against threats, and successfully reproduced.

Human agriculture, in contrast, is only about 10,000 years old, and much of it operates unsustainably, requiring constant new inputs and leaving degraded land in its wake. We've achieved tremendous yields and fed billions, but often at significant environmental cost.

When a queen leafcutter ant carries her fungus sample to start a new colony, she's continuing an unbroken agricultural tradition spanning 50 million years - longer than humans have existed as a species.

The study of leafcutter ant agriculture sits at the intersection of basic biology, applied agriculture, and biomimicry engineering. As researchers like Montoya's team continue to uncover the subtle complexities of these systems, we gain both knowledge and humility.

We're learning that relationships we dismissed as simple parasitism may actually be nuanced ecological partnerships. We're discovering that waste management and hygiene, not chemical warfare, form the foundation of sustainable disease control. We're recognizing that specialized labor and mutualistic relationships create resilient systems that withstand disruption.

Perhaps most importantly, we're being reminded that solutions to our problems may already exist in nature, refined over timeframes that dwarf human history. The question isn't whether leafcutter ants can teach us about agriculture - they already have. The question is whether we're willing to learn.

As climate change forces us to rethink food production and resource management, these tiny farmers offer a roadmap. Not a blueprint to copy directly - we're not ants, and our crops aren't fungus - but a set of principles proven over deep time. Closed-loop systems. Waste as resource. Mutualistic partnerships. Adaptation through diversity.

The ants figured this out 50 million years ago. Maybe it's time we caught up.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

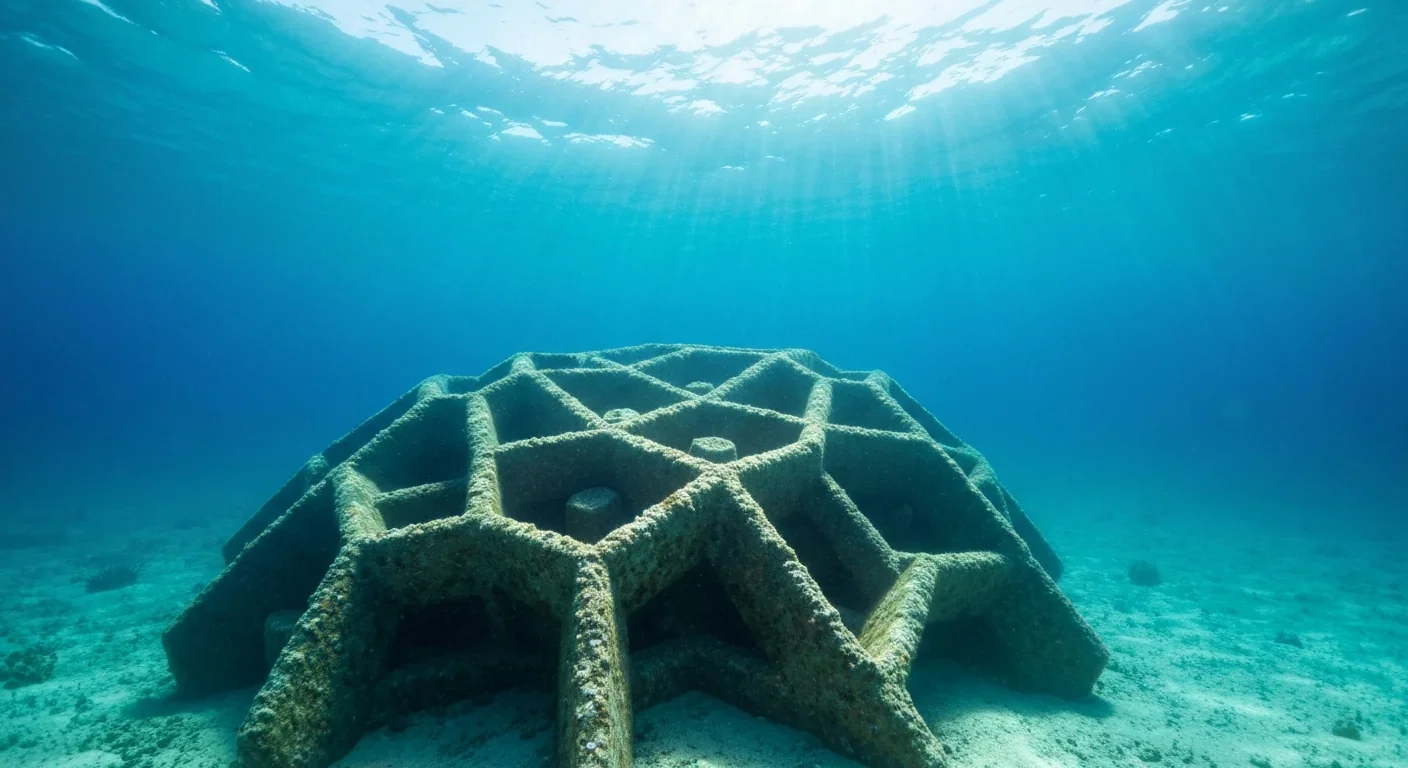

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

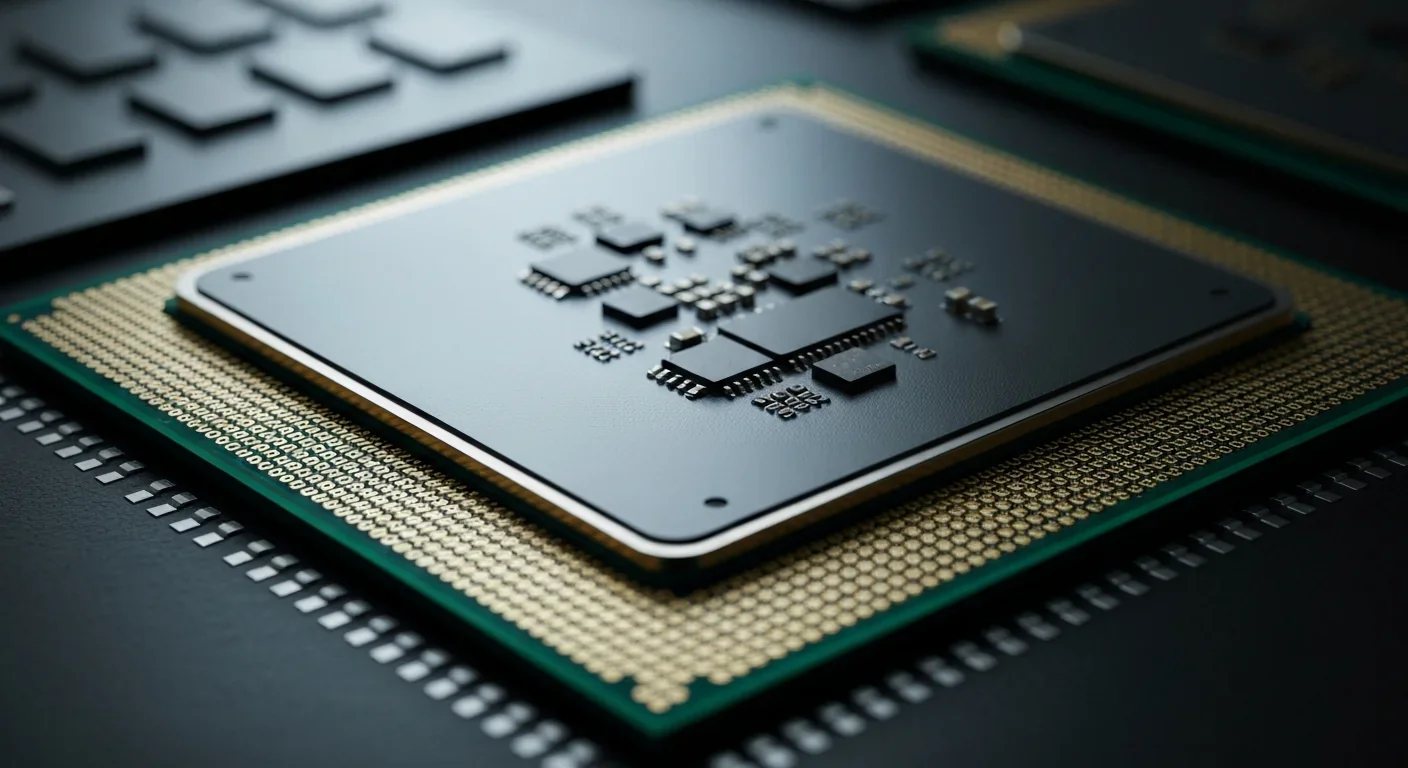

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.