Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Acacia trees have evolved specialized structures - hollow thorns for housing, extrafloral nectar, and protein-rich Beltian bodies - to sustain aggressive ant colonies that defend them from herbivores and pathogens, creating one of nature's most remarkable obligate mutualisms.

Walk through a Central American forest, and you might brush against what looks like an ordinary acacia tree. Within seconds, you'll discover it's anything but ordinary. Hundreds of aggressive ants will swarm from the tree's hollow thorns, ready to attack anything that dares disturb their fortress. This isn't coincidence - it's one of nature's most remarkable security contracts, millions of years in the making.

Acacia trees have evolved to essentially pay mercenaries to patrol their branches 24/7. They provide housing, food, and everything an ant colony needs to thrive. In exchange, these tiny soldiers create a living defense system that would make any bodyguard jealous. It's mutualism at its most extreme - both species have become so dependent on each other that neither can survive alone.

The partnership begins with specialized structures that transform a simple tree into an ant fortress. Bullhorn acacias - the classic example from Central America - develop massive hollow thorns called domatia, some as large as a human thumb. These aren't just random cavities. The tree grows them specifically as ant apartments, complete with thin walls that newly mated ant queens can easily chew through to establish their colonies.

But housing alone won't sustain an army. Acacias go further by producing two types of food that meet all their tenants' nutritional needs. Extrafloral nectaries - specialized glands at the base of leaves - secrete nectar rich in sugars and amino acids. At the tips of leaflets grow Beltian bodies, protein-packed nuggets containing up to 20% protein and 15% lipids. These nutritional packets look like tiny golden beads and are named after Thomas Belt, the 19th-century naturalist who first described them.

Research shows that acacia nectar contains a chitinase enzyme that specifically inhibits the ants' sucrose invertase - ensuring the ants remain faithful to their host tree rather than foraging elsewhere. It's biochemical loyalty enforcement.

Research shows that acacia nectar contains a clever manipulation mechanism. The nectar includes a chitinase enzyme that specifically inhibits the ants' sucrose invertase - the enzyme they need to digest other sugar sources. This ensures the ants remain faithful to their host tree rather than foraging elsewhere. It's biochemical loyalty enforcement.

These structures don't appear randomly. A 2019 study published in PNAS revealed that acacias use microRNAs - specifically miR156 and miR157 - to control the timing of when these ant-attracting traits develop. As the tree matures and these microRNA levels decline, the plant begins producing the swollen thorns, nectaries, and Beltian bodies in a precise developmental sequence. This timing is crucial because young seedlings can't support a full ant colony, so they delay producing these expensive structures until they're large enough to benefit from the protection.

Not just any ant will do. Pseudomyrmex ferruginea is the classic partner for bullhorn acacias in Central America, though several Pseudomyrmex species form similar relationships. These ants are uniquely suited to their role. They're aggressive, fast, and equipped with powerful stings that can repel creatures far larger than themselves - from beetles to elephants.

The partnership begins when a newly mated queen, attracted by chemical signals from the tree, lands on a young acacia and searches for a suitable thorn. She chews a small entrance hole, establishes her nest inside, and lays 15-20 eggs. Those first workers are critical - they'll determine whether the colony thrives or fails.

Colony growth follows predictable patterns. Within seven months, the population reaches about 150 workers. Three months later, it doubles to 300. After two years, a successful colony numbers around 1,100 ants. By the third year, a single tree can host over 4,000 ant workers, all patrolling branches, harvesting Beltian bodies, and defending their home with ferocious dedication.

"A single tree can host colonies of up to several thousand ants reaching over 4,000 individuals after three years."

- Research on Pseudomyrmex ferruginea colonies

African acacias employ different mercenaries. Vachellia drepanolobium - the whistling thorn of East African savannas - hosts Crematogaster and Tetraponera species. These partnerships show fascinating variations. Crematogaster nigriceps ants actually prune their host tree's bud growth to reduce lateral branching, effectively shaping the tree's architecture. Tetraponera penzigi takes a different approach, destroying the tree's nectar glands to eliminate resources that might attract competing ant species.

These ants aren't just passive residents. They patrol constantly, investigating disturbances and responding to threats with coordinated aggression that escalates as colony size increases. When a colony reaches 200-400 workers, defensive behavior intensifies dramatically, with ants becoming more aggressive and covering more territory.

How do ants know when their tree needs defending? Chemical communication is key. When a leaf is damaged - by a chewing insect, a browsing mammal, or even a curious human - the plant releases volatile organic compounds. The most important is trans-2-hexenal, a six-carbon aldehyde that acts as a distress signal.

Researchers tested this by applying trans-2-hexenal and a control solvent to acacia branches. The difference was dramatic. Branches treated with the compound saw ants swarming the area within seconds, displaying aggressive behavior and searching for intruders. Control branches attracted little attention. This shows the ants aren't just randomly patrolling - they're responding to specific chemical cues that indicate their home is under attack.

The defensive strategy is multilayered. Ants use their powerful mandibles to cut away vines and strangling plants that compete with their host for sunlight. They attack herbivorous insects before they can cause significant damage. When large mammals like elephants or giraffes approach to browse on tender acacia leaves, hundreds of ants swarm onto the animal's trunk or face, stinging and biting until the herbivore moves on to an easier meal.

The effectiveness of this defense is hard to overstate. When scientists removed ant colonies from bullhorn acacias, leaving the trees defenseless, predators completely defoliated them. The results were consistent and dramatic - without their ant bodyguards, these trees cannot survive in their natural habitat.

When scientists removed ant colonies from bullhorn acacias, predators completely defoliated the defenseless trees. Without their ant bodyguards, these trees cannot survive in their natural habitat.

But protection goes beyond just fighting off herbivores. Research published in 2014 discovered that ants produce methanol-like compounds that inhibit bacterial growth on acacia leaves. Trees with ant colonies showed significantly fewer instances of bacterial disease compared to unoccupied acacias. The ants are providing antibiotic protection, turning leaf surfaces into hostile environments for pathogens.

Some ant species also protect scale insects that feed on acacia sap, harvesting the honeydew these insects produce as an additional food source. This creates a complex three-way relationship where the ants tolerate minor harm to their host in exchange for supplemental nutrition. It's not a perfect partnership - there are tensions and trade-offs.

How did such an intricate partnership evolve? The answer lies millions of years in the past, though the exact timeline remains uncertain. What we know is that this represents obligate mutualism - both partners have become so specialized that they can no longer survive independently.

The evolutionary pressure came from herbivory. Acacia trees faced constant attack from insects and browsing mammals. Most plants respond by producing chemical defenses - bitter alkaloids and toxic compounds that make their leaves unpalatable. But chemicals are expensive to produce and maintain. Bullhorn acacias took a different evolutionary path - they reduced or eliminated chemical defenses and instead invested in structures that attract and maintain ant colonies.

This created a feedback loop. Trees that produced better housing and food attracted larger, more aggressive ant colonies. Those trees suffered less herbivore damage and produced more offspring. Meanwhile, ants that were more effective at defending their host trees had more food and better shelter, allowing their colonies to grow larger and produce more queens.

Co-evolution shaped both partners. A recent study comparing ecological niches found that mutualistic ant-acacia pairs show significantly greater niche overlap than random pairings would predict. The partnership didn't just create specialized behaviors - it reshaped the fundamental ecological spaces both species occupy. Ants that originally lived in moist forest understories evolved to thrive in dry savanna habitats, simply because that's where their acacia partners grew.

"There is a cost associated with making these traits, but the plant needs them, otherwise it's a goner. No ants, no plants."

- Scott Poethig, University of Pennsylvania

The genetic mechanisms underlying this partnership are elegant. The same microRNA pathways that control normal plant development - transitioning from juvenile to mature growth phases - were co-opted to regulate ant-attracting structures. This means acacias didn't evolve entirely new genetic programs for mutualism. Instead, they repurposed existing developmental controls, adding new outputs to ancient regulatory circuits.

Interestingly, environmental conditions can modulate this system. When acacias grow in shade, they maintain higher levels of miR156/157 microRNAs, delaying the development of thorns and other ant-attracting features. This makes evolutionary sense - plants in low-light conditions don't have the energy surplus to support ant colonies, so they postpone the partnership until they reach better-lit areas where photosynthesis can support the extra metabolic cost.

While Central American bullhorn acacias get most of the attention, ant-acacia partnerships occur across multiple continents with fascinating regional variations. In East Africa, Vachellia drepanolobium - the whistling thorn - dominates upland habitats. Its partnership with Crematogaster ants differs in key details. Whistling thorns don't produce Beltian bodies, relying instead on extrafloral nectar and the honeydew from scale insects.

The "whistling" name comes from an unexpected consequence of the mutualism. When ants abandon certain thorns or when holes created by beetles pierce the thorn walls, wind passing through creates an eerie whistling sound that carries across the savanna. It's an acoustic byproduct of architectural defenses.

African ant-acacia relationships also display different competitive dynamics. Multiple ant species may compete for the same tree, with different species showing different strategies. Some focus on aggressive defense, while others manipulate the tree's growth patterns to reduce resources available to competitors. This suggests that even within the mutualism framework, individual ant species pursue different strategies to maximize their own fitness.

Intriguingly, some swollen-spine acacias remain unoccupied by obligate ant partners yet show little herbivore damage. Species like Vachellia cookii, V. globulifera, and V. ruddiae in Central America possess the anatomical structures for ant mutualism but don't always host colonies. This suggests these species retain alternative defense mechanisms or that local herbivore pressure varies enough that the trees can sometimes survive without their bodyguards.

Many African acacia species with hollow thorns remain understudied. Species including Vachellia bullockii, V. bussei, V. erioloba, and nearly a dozen others produce domatia but their ant partners haven't been systematically cataloged. There's likely enormous variation in partnership intensity, specificity, and evolutionary outcomes waiting to be discovered.

The mutualism isn't invincible. Recent experimental work reveals that environmental context matters enormously. When researchers excluded large herbivores like elephants and giraffes from areas of Kenyan savanna, whistling thorn trees responded by reducing the number of nectar glands and swollen spines they produced. With less herbivore pressure, maintaining ant colonies became an unnecessary expense.

The consequences were counterintuitive and alarming. As trees reduced resources for ants, the ant colonies weakened. But this didn't lead to healthier trees - instead, trees became infested with sap-sucking insects that the diminished ant colonies could no longer control effectively. Trees actually became less healthy when herbivore pressure decreased because it disrupted the delicate balance that had evolved over millions of years.

When large herbivores were excluded from African savannas, acacias reduced their investment in ant colonies - but paradoxically became less healthy as weakened ant defenses allowed sap-sucking insects to proliferate.

This shows how mutualism can create dependency traps. Once a species abandons one defense strategy for another, going back becomes difficult or impossible. Ant-acacias have largely lost the genetic machinery for producing chemical defenses. Without their ant partners, they're vulnerable.

Climate change may stress these partnerships in unpredictable ways. If warming temperatures shift the geographic ranges of acacias but not their ant partners - or vice versa - the mutualism could collapse in certain regions. Similarly, changes in seasonal rainfall patterns might disrupt the timing of when trees produce ant-attracting structures and when ant queens are searching for nest sites.

The acacia-ant relationship exemplifies principles that extend far beyond this particular partnership. Obligate mutualism demonstrates that cooperation can be as powerful an evolutionary force as competition. Species that successfully trade resources and services can access ecological niches neither could occupy alone.

This partnership also shows that cooperation doesn't require altruism or conscious intent. Both acacias and ants are simply maximizing their own evolutionary fitness. The tree isn't being generous by providing food and shelter - it's buying protection. The ants aren't performing a service out of kindness - they're defending their food source and home. Yet from these purely selfish motivations emerges a system of mutual benefit that has persisted for millions of years.

The specificity of the relationship demonstrates how coevolution can lock species together. The chitinase in acacia nectar that inhibits ant digestive enzymes isn't a feature that would evolve in a general plant-pollinator relationship. It only makes sense as a mechanism to ensure ant fidelity in an obligate partnership. Similarly, the ants' sensitivity to trans-2-hexenal and their aggressive response to this specific compound reflect evolutionary fine-tuning to their particular host.

Modern research continues to reveal new layers of this ancient partnership. The discovery that ants provide antimicrobial protection was unexpected - it means the defensive role is even more comprehensive than scientists initially thought. Each study seems to find another dimension to the cooperation, from genetic regulatory mechanisms to complex three-way interactions involving scale insects and pathogens.

From an ecological perspective, these trees and their ant bodyguards serve as foundational species that structure entire forest communities. Other organisms have evolved to specialize on ant-acacias, creating cascading effects through the ecosystem. Some beetles specialize in inhabiting abandoned ant domatia. Certain parasitic wasps target ant-acacia colonies specifically. The mutualism creates a unique ecological environment that supports biodiversity in ways we're only beginning to understand.

Understanding acacia-ant mutualism isn't just an academic exercise. These relationships serve as natural laboratories for studying cooperation, communication, and coevolution. The principles revealed by studying these partnerships apply to understanding symbioses throughout biology - from coral reefs to human gut microbiomes.

Conservation implications are significant. You can't conserve ant-acacias by protecting just the trees or just the ants. The partnership is the unit that matters. This means preserving the complex ecological context - the herbivore populations that create selective pressure for defense, the environmental conditions that allow both partners to thrive, and the timing mechanisms that allow queen ants to find suitable host seedlings.

As forests face increasing pressure from climate change, habitat fragmentation, and human development, understanding these intricate partnerships becomes more urgent. If seasonal patterns shift or temperature ranges change, will queens still arrive at the right time to colonize young acacias? Will the trees still develop their ant-attracting structures on the correct schedule? These aren't simple questions, and the answers will determine whether these remarkable relationships persist into the next century.

"Without these little defenders, the acacia would collapse, ultimately altering the whole forest."

- Elyse C. McCormick, Science Writer

What started as a simple observation by Victorian naturalists - ants living in hollow thorns - has revealed itself to be one of evolution's most elegant solutions to the problem of defense. The acacia-ant partnership shows that in nature, sometimes the best security system isn't a weapon or armor, but a good contract with the right mercenaries. Millions of years of coevolution have produced a system where both partners benefit, neither can survive alone, and the forest ecosystem is richer for their cooperation.

The next time you see an acacia tree, look closer at those thorns. They're not just passive defenses - they're apartment complexes, stocked with food, housing an army that's been defending that lineage for millions of years. That's not just cooperation. That's a security contract written in DNA, enforced by evolution, and as relevant today as it was when the first queen ant chewed her way into the first hollow thorn.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

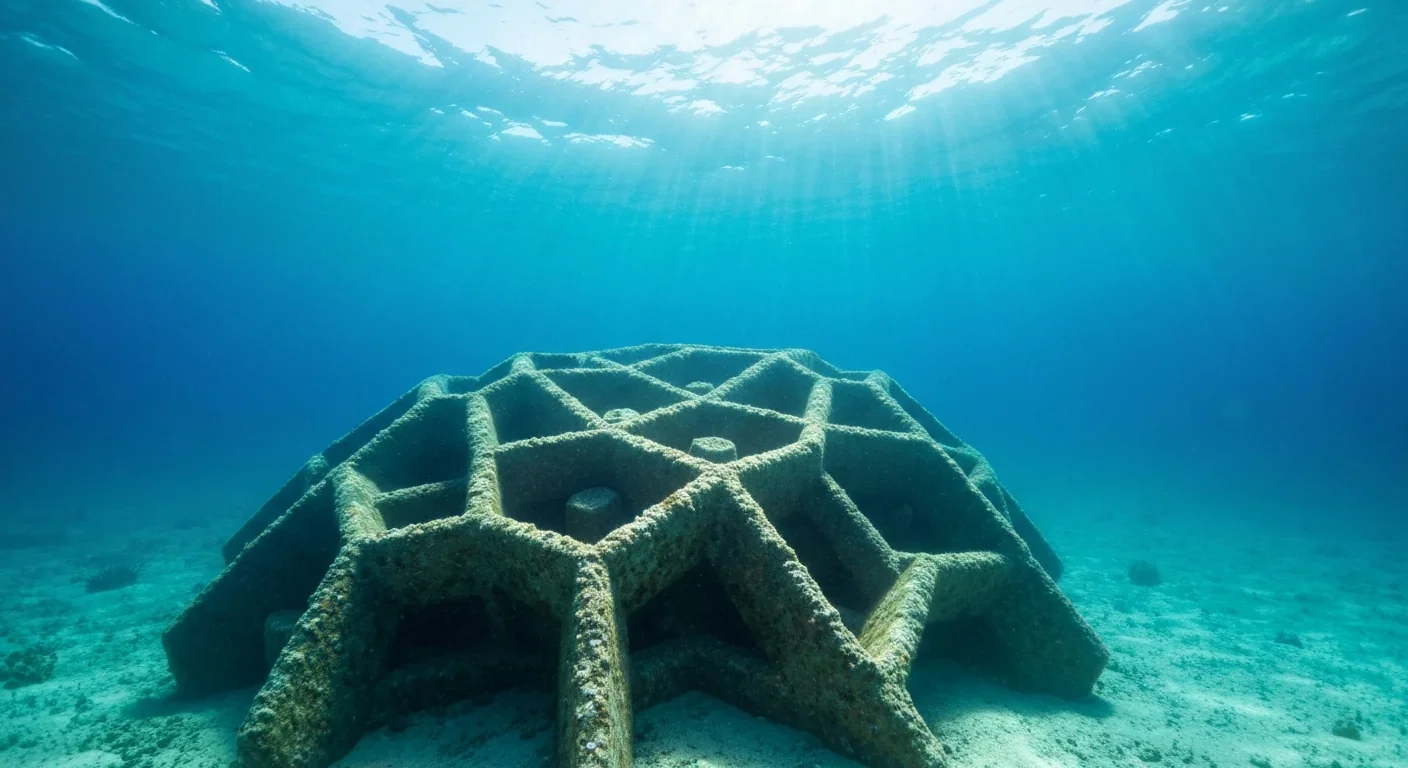

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

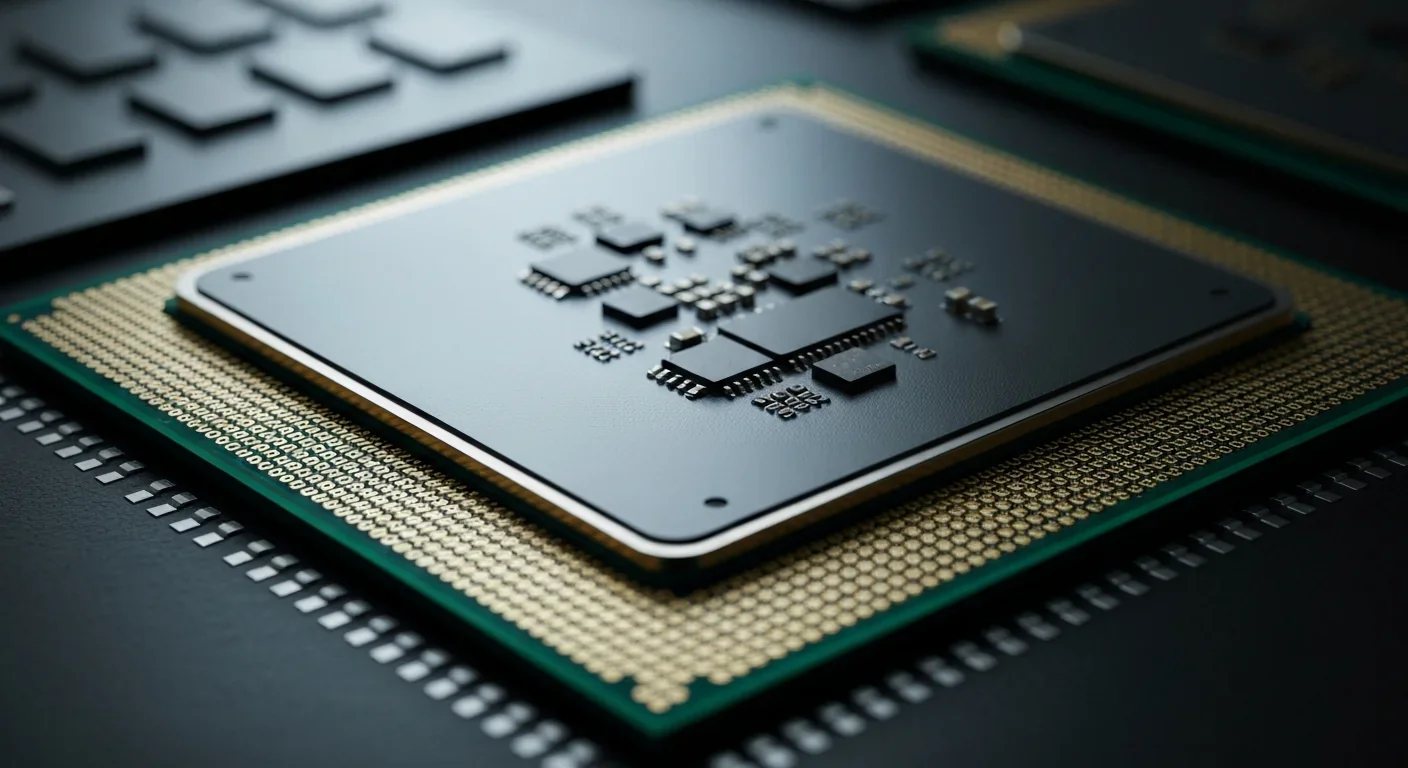

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.