How Ants Cracked the Code to Perfect Optimization

TL;DR: In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

In 1977, scientists aboard the submersible Alvin made a discovery that shattered fundamental assumptions about life on Earth. Nearly two miles beneath the Pacific Ocean's surface, where sunlight never penetrates and crushing pressure should render life impossible, they found thriving ecosystems surrounding volcanic vents spewing superheated water. Giant tube worms, ghostly crabs, and clouds of bacteria clustered around these underwater chimneys, surviving not on energy from the sun but from chemicals belching from Earth's crust. The revelation was so unexpected that one scientist reportedly exclaimed, "Isn't the deep ocean supposed to be like a desert?" This discovery didn't just expand our understanding of where life can exist; it fundamentally changed how we think about life's origins on Earth and its potential elsewhere in the universe.

The 1977 discovery of hydrothermal vents at the Galápagos Rift represented one of the most significant biological findings of the 20th century. Marine geologist Jack Corliss and his team were exploring seafloor spreading zones when they encountered something unprecedented: entire ecosystems flourishing in perpetual darkness, sustained by a process called chemosynthesis rather than photosynthesis.

Unlike virtually all life at Earth's surface, which depends directly or indirectly on sunlight captured by plants and algae, these vent communities derive their energy from chemicals in the superheated water. Bacteria convert hydrogen sulfide, methane, and other compounds into organic matter, forming the foundation of a food web as complex as any coral reef. Two years later, during the 1979 RISE expedition, Alvin discovered even more dramatic vents on the East Pacific Rise, where black smoker chimneys belched water heated to 380°C, hot enough to melt lead.

Before 1977, biology textbooks taught that all ecosystems ultimately depend on the sun. Hydrothermal vents proved that fundamental assumption wrong.

The implications rippled through multiple scientific disciplines. Biologists had to reconsider the fundamental requirements for life. Geologists gained new insights into Earth's internal heat and chemistry. And astrobiologists suddenly had a compelling model for how life might exist on worlds with subsurface oceans like Jupiter's moon Europa or Saturn's moon Enceladus.

At the heart of these ecosystems lies a process that mirrors photosynthesis but replaces sunlight with chemical energy. Chemosynthetic bacteria oxidize reduced compounds such as hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), methane (CH₄), and hydrogen gas (H₂), using the released energy to convert carbon dioxide into organic molecules.

The basic chemosynthetic reaction for hydrogen sulfide oxidation is remarkably elegant:

CO₂ + 4H₂S + O₂ → CH₂O + 4S + 3H₂O

This equation represents not just chemistry but a complete reimagining of life's energy economy. Where photosynthetic organisms capture light energy to split water and fix carbon, chemosynthetic bacteria harness the potential energy locked in Earth's geological processes. The hot, mineral-rich fluid emerging from vents contains reducing agents from Earth's mantle and crust, while cold seawater provides the oxygen needed to oxidize them. The interface between these two fluids creates a chemical gradient that's essentially a battery, and microbes have evolved to tap that power.

Different species of bacteria specialize in different chemical reactions. Some oxidize iron or manganese. Others metabolize ammonia or nitrite. This metabolic diversity means vent microbial communities can exploit nearly every available energy source, creating remarkably efficient ecosystems. Research published in Frontiers in Microbiology showed that chimneys along the submarine Ring of Fire harbor distinct microbial assemblages based on temperature, chemistry, and mineral composition.

The biodiversity around hydrothermal vents rivals tropical rainforests in its strangeness and specialization. Perhaps the most iconic resident is Riftia pachyptila, the giant tube worm, which can grow up to eight feet long. These crimson-plumed creatures lack mouths, stomachs, and digestive systems entirely. Instead, they house billions of chemosynthetic bacteria in a specialized organ called a trophosome, which can constitute up to half the worm's body weight.

The relationship between Riftia and its bacterial partners represents one of nature's most extreme symbioses. The worm's blood contains specialized hemoglobin that binds both oxygen and hydrogen sulfide - normally a deadly poison - without allowing them to react. The worm extends its bright red plume into the water to absorb both chemicals, then transports them to its bacterial symbionts. The bacteria oxidize the hydrogen sulfide for energy and share the resulting organic compounds with their host. This arrangement allows Riftia to grow faster than any other marine invertebrate, sometimes adding nearly three feet per year.

"These crimson-plumed creatures lack mouths, stomachs, and digestive systems entirely - yet they thrive in one of Earth's harshest environments through pure symbiosis."

- Marine Biology Research

But tube worms are just the beginning. Vent ecosystems host species found nowhere else on Earth: eyeless shrimp that crowd around black smokers in such numbers they're called "shrimp blizzards," their bodies adapted to detect faint infrared radiation from the superheated water; ghostly white crabs that scavenge whatever organic matter drifts by; and mussels and clams that also harbor chemosynthetic bacteria in their gills.

One of the most extreme organisms discovered is the Pompeii worm (Alvinella pompejana), which colonizes the sides of black smoker chimneys where temperatures reach 80°C - the highest temperature known to support animal life. The worm's head is typically at around 22°C while its tail experiences nearly boiling conditions, creating a temperature gradient along its body that would kill virtually any other complex organism. Its secret? A fleece-like covering of bacteria that may provide insulation and possibly metabolize toxins in the worm's environment.

Since their initial discovery, hydrothermal vents have been found throughout the world's oceans, wherever tectonic plates spread apart or collide. The global distribution reveals thousands of vent sites along mid-ocean ridges - the 40,000-mile-long underwater mountain chain that circles the globe like the seam on a baseball. Major vent fields exist along the East Pacific Rise, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, and the Juan de Fuca Ridge off the Pacific Northwest.

Recent explorations have revealed that vent ecosystems are far more diverse than initially thought. Black smokers form where superheated water (300-400°C) laden with metal sulfides erupts rapidly, creating mineral chimneys that grow like stalagmites. When the minerals precipitate, they form black particles that make the water look like smoke.

White smokers are cooler (generally below 300°C) and rich in lighter minerals like barium, calcium, and silicon. The Lost City Hydrothermal Field, discovered in 2000 on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, represents an entirely different type of system. Unlike volcanic black smokers driven by magma, Lost City vents result from a chemical reaction between seawater and mantle rocks - a process called serpentinization. These vents produce alkaline fluids rich in hydrogen and methane, sustaining microbial communities without requiring input from volcanic heat. The Lost City's white carbonate spires tower up to 200 feet, some having vented continuously for more than 120,000 years.

In December 2024, scientists announced the discovery of diverse hydrothermal vent styles in the Arctic Ocean, including vents with unusual temperature profiles and mineral compositions. That same month, researchers reported finding a massive hydrothermal field off Greece in the Mediterranean, suggesting active vent systems may be more widespread than previously recognized.

In 2025, scientists discovered creatures living beneath hydrothermal vents, in the volcanic rock below the seafloor - expanding the known boundaries of where life can exist.

Even more surprising was the 2025 discovery reported in National Geographic: scientists found creatures living beneath hydrothermal vents, in the porous volcanic rock below the seafloor. Worms and microbes inhabited this subsurface environment, expanding the known habitat range for vent fauna and raising questions about how nutrients and energy circulate through these hidden ecosystems.

Hydrothermal vents are nature's laboratory for extremophiles - organisms that thrive in conditions that would quickly kill most life forms. The microbes living around vents face challenges that read like a list of torture devices: crushing pressures exceeding 200 atmospheres, temperatures from near freezing to above the boiling point of water, toxic concentrations of heavy metals and sulfides, pH levels ranging from battery acid to drain cleaner, and complete absence of sunlight.

Thermophiles love heat, thriving at temperatures between 45°C and 80°C, while hyperthermophiles prefer even hotter conditions, up to 122°C. One archaeon, Methanopyrus kandleri, holds the record for surviving at 122°C under high pressure - the highest temperature known to support life. These organisms have evolved specialized proteins and membrane structures that remain stable at temperatures that would cause normal biomolecules to denature and fall apart.

The enzymes from thermophiles have become invaluable to biotechnology. Taq polymerase, isolated from the thermophile Thermus aquaticus found in Yellowstone hot springs, revolutionized molecular biology by enabling the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique used in everything from criminal forensics to COVID-19 testing. Researchers are actively exploring hydrothermal vent microbes for novel enzymes, antibiotics, and other biochemical tools that function in extreme conditions.

The microbial communities around vents also include acidophiles that flourish at pH 2-3, alkaliphiles that prefer pH 9-11, and barophiles adapted to extreme pressure. Some species combine multiple extremophile traits - thermoacidophiles, for instance, thrive in both hot and acidic conditions. The Distribution of thermoacidophilic "Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vent Euryarchaeota 2" spans multiple ocean basins, suggesting these organisms can disperse across thousands of miles of deep ocean and colonize new vents as they form.

The discovery of vent ecosystems immediately sparked speculation about whether life itself might have originated in similar environments. Several characteristics make hydrothermal vents plausible settings for abiogenesis - the emergence of life from non-living chemistry.

First, vents provide abundant chemical energy independent of sunlight. Research from University College London demonstrated that alkaline hydrothermal vents create natural proton gradients across mineral membranes, similar to the gradients that power ATP synthesis in modern cells. This suggests early metabolisms might have piggybacked on geologically created gradients before evolving their own membrane-bound systems.

Second, the mineral surfaces in vent chimneys can catalyze organic reactions. Iron sulfide minerals, common in vent structures, can facilitate the synthesis of organic molecules from simple precursors. In the laboratory, researchers have shown that vent-like conditions can produce amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, and even primitive cell-like structures called protocells.

"Alkaline hydrothermal vents create natural proton gradients across mineral membranes, similar to the gradients that power modern cells - suggesting life might have originated in these environments."

- University College London Research Team

Third, vents provide shelter and concentration. The porous structure of mineral chimneys creates countless micro-compartments where organic molecules can accumulate and interact, protected from being diluted in the vast ocean. Studies published in ScienceDaily show that temperature gradients at vents can drive thermophoresis, a process that concentrates molecules on the cooler side of temperature gradients - essentially creating natural test tubes.

The hydrothermal vent theory faces competition from other origin-of-life scenarios, including primordial tidal pools, subsurface environments in Earth's crust, and even the possibility that life arrived from space. But vent scenarios have a compelling advantage: hydrothermal systems would have been abundant on early Earth, and they provide all three essentials for life - energy, chemical building blocks, and compartmentalization - in one location.

Intriguingly, molecular evidence supports an ancient connection to heat-loving microbes. Some analyses of evolutionary trees suggest that the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all life on Earth may have been a thermophile living in a hydrothermal environment around 4 billion years ago. While this doesn't prove life originated at vents, it suggests our earliest ancestors were comfortable in those conditions.

The astrobiology implications of hydrothermal vent ecosystems cannot be overstated. If life can flourish in Earth's deep ocean, independent of sunlight and isolated from the surface, then similar ecosystems might exist on other worlds with subsurface oceans.

Europa, Jupiter's ice-covered moon, is thought to harbor a global ocean beneath its frozen crust, possibly 60 miles deep. Tidal flexing from Jupiter's immense gravity heats Europa's interior, and scientists strongly suspect the ocean floor hosts hydrothermal vents. A Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences paper analyzed Europa's potential for chemoautotrophy - life based on chemosynthesis - and concluded that Europa's ocean likely contains all the necessary ingredients: chemical energy sources, appropriate temperature gradients, and mineral surfaces that could catalyze organic chemistry.

Enceladus, Saturn's small but fascinating moon, actively vents material from its subsurface ocean into space through cracks in its south polar ice. The Cassini spacecraft flew through these plumes and detected water vapor, salt, silica particles, and organic molecules including complex hydrocarbons. The silica particles strongly suggest hydrothermal activity at temperatures around 90°C on Enceladus's ocean floor. Some researchers argue that Enceladus's ocean represents one of the most promising locations in the solar system to search for extraterrestrial life.

If similar ecosystems exist on Europa or Enceladus, we might not need to look to distant star systems to find alien life - it could be waiting in our own solar system's hidden oceans.

Other candidates include Saturn's moon Titan, which has liquid methane lakes on its surface and possibly a subsurface water ocean, and even distant moons like Neptune's Triton. The key insight from Earth's hydrothermal vents is that life doesn't need a sun - it just needs chemical disequilibrium, liquid water, and time.

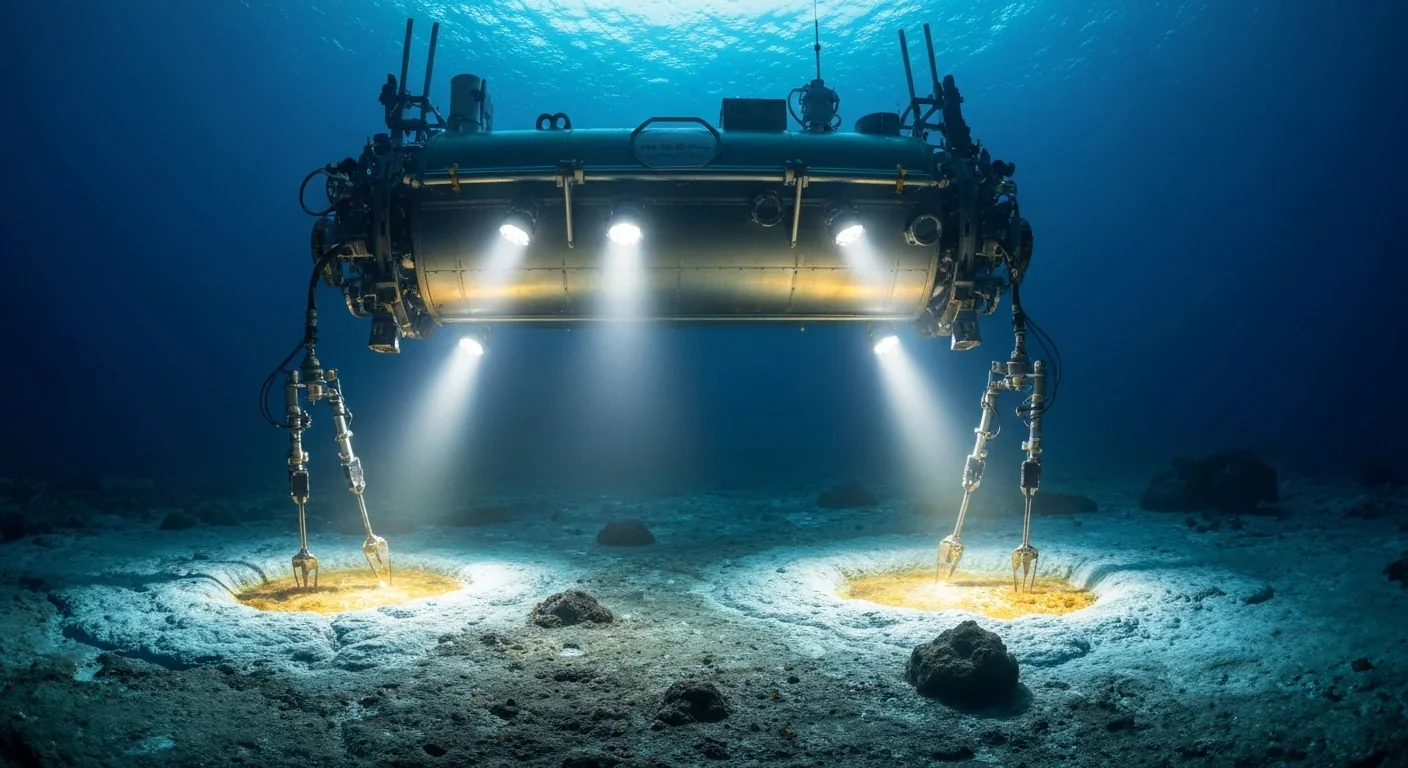

Exploring hydrothermal vents requires some of humanity's most sophisticated technology. The depth alone presents enormous challenges. At 2,500 meters (8,200 feet), the pressure is 250 times atmospheric pressure at sea level. At the deepest vents, pressures exceed 400 atmospheres. The environment is corrosive, lightless, and often geologically active.

DSV Alvin, the submersible that discovered the first vents, has been repeatedly upgraded over its 60-year career. A major refit in 2022 gave Alvin a new titanium pressure hull capable of reaching 6,500 meters, allowing it to access nearly two-thirds of the ocean floor. The submersible carries three people - a pilot and two scientists - for dives lasting up to ten hours.

Remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) have become indispensable for vent research. Unlike piloted submersibles, ROVs are tethered robots controlled from a surface ship. This allows them to spend days or weeks at depth, manipulated by pilots who work in shifts. ROVs can collect samples, deploy instruments, and capture high-definition video without risking human lives. Japan's Kaikō ROV reached the Challenger Deep, the ocean's deepest point, demonstrating that even the most extreme depths are now accessible.

Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) survey vast areas of seafloor without a tether, using pre-programmed routes and advanced sensors. They've been crucial for discovering new vent fields in remote regions. Recent expeditions to the Mariana Islands have combined all three technologies - submersibles, ROVs, and AUVs - to create comprehensive maps of underwater volcanic systems.

The latest generation of tools includes sensors that can remain at vents for months or years, monitoring temperature, chemistry, and biological activity over time. This long-term data reveals that vent ecosystems are far more dynamic than early studies suggested, with populations shifting in response to changes in vent activity, and even persisting in dormant vents long after active venting has ceased.

While exploring hydrothermal vents, scientists discovered related ecosystems based on similar principles but different chemistry. Cold seeps occur where hydrocarbon-rich fluids - methane, hydrogen sulfide, or petroleum - percolate through seafloor sediments. Unlike the explosive emergence of vent fluids, seeps release their chemicals slowly, but they similarly support chemosynthetic ecosystems.

Cold seep communities feature tube worms, clams, and mussels that look remarkably like their vent relatives, even though the two ecosystem types may be separated by hundreds or thousands of miles. This convergent evolution - similar solutions arising independently - suggests that chemosynthesis-based ecosystems follow certain predictable patterns. Methane-oxidizing bacteria form the base of seep food webs, either living free in the sediments or in symbiosis with animals.

Cold seeps have been discovered worldwide, from the Gulf of Mexico to the Mediterranean to the waters off Japan. One seep ecosystem called the "Brine Pool" in the Gulf of Mexico features a literal lake of super-salty water on the seafloor, toxic to most life but surrounded by a ring of mussels whose symbionts metabolize methane.

Even more surprising, scientists have found chemosynthetic communities not associated with any obvious fluid source. In 2025, researchers reported discovering a deep-sea "hotspot" bursting with life in an area previously thought to be barren. Analysis suggested the ecosystem was supported by diffuse seepage of chemicals through the seafloor, detectable only with sensitive instruments.

Taken together, these discoveries paint a picture of Earth's deep ocean not as a uniform, lifeless plain but as a mosaic of hidden oases, each powered by geological chemistry and hosting unique communities of specialized organisms.

Despite their isolation, hydrothermal vent ecosystems face anthropogenic threats. The most immediate is deep-sea mining. Hydrothermal vents deposit metal-rich minerals - copper, zinc, gold, silver - on the seafloor. Extinct vent sites in particular are sought by mining companies because the mineral deposits have accumulated over millennia without being buried by sediment.

A Frontiers in Marine Science analysis of deep-sea mining impacts concluded that extraction activities would devastate vent ecosystems. The mining equipment would physically destroy habitat, stir up sediment clouds that could smother organisms miles away, and potentially contaminate the water column with metals and processing chemicals. Because vent organisms are slow-growing and highly specialized, recovery could take decades or centuries - or might not occur at all.

Complicating conservation efforts is the reality that we've only begun to catalog vent biodiversity. An estimated 90% of vent species remain undescribed, and many may exist in only one or a few vent fields. Mining a site could erase species before science even knows they exist.

There's also the concern about disrupting biogeochemical cycles. Research published in 2023 showed that hydrothermal vents are a significant source of dissolved iron, which eventually reaches the surface ocean where it fertilizes phytoplankton growth. The vents also influence deep ocean chemistry and may play a role in long-term carbon cycling. Large-scale disruption could have knock-on effects we don't yet understand.

International governance is complicated because many vent sites lie outside any nation's territorial waters. The International Seabed Authority is developing regulations for deep-sea mining, but environmental groups argue the rules don't provide adequate protection. Several nations have called for a moratorium on deep-sea mining until we better understand these ecosystems, but political and economic pressures continue to push exploration forward.

Perhaps the deepest lesson from hydrothermal vents is about life's resilience and opportunism. These ecosystems demonstrate that life doesn't require ideal conditions - it only needs a source of energy and a way to harness it. The gulf between "too extreme for life" and "a thriving ecosystem" turns out to be remarkably narrow.

This adaptability has profound implications. It suggests life is not a delicate flower requiring just-right conditions but a robust phenomenon capable of exploiting almost any available energy gradient. This makes the search for extraterrestrial life more optimistic: if Earth can harbor thriving communities in crushing pressure, scalding temperatures, toxic chemistry, and eternal darkness, the range of potentially habitable environments elsewhere in the universe expands dramatically.

The metabolic diversity around vents also illustrates evolution's problem-solving power. Faced with an environment utterly different from the sunlit surface, organisms didn't just adapt - they innovated. They formed symbioses, abandoned digestive systems, evolved tolerance to toxins, and colonized the most improbable niches. This creativity, encoded in genes and refined over millions of years, reminds us that life's history is as much about exploration and experimentation as it is about survival.

Technology continues to advance, promising new discoveries in the deep. Plans are underway for next-generation submersibles capable of reaching any point in the ocean, including the hadal zone - the deepest ocean trenches below 6,000 meters. Imagine exploring hydrothermal vents in the Challenger Deep, seven miles down, where pressure exceeds 1,000 atmospheres.

Sophisticated molecular techniques are revealing previously unknown microbial diversity. Environmental DNA sequencing can detect organisms without needing to see or culture them, uncovering "microbial dark matter" - lineages of life that have escaped detection. Some of these organisms might possess biochemical pathways unknown to science, potentially useful for biotechnology.

Long-term monitoring programs are beginning to reveal how vent ecosystems respond to volcanic eruptions, which can obliterate entire communities overnight. Surprisingly, recolonization happens relatively quickly - within months to a few years - suggesting that vent larvae can disperse across vast distances or that some organisms survive the eruptions in protected refuges. Understanding these dynamics helps illuminate how life persists in unstable environments, knowledge relevant to everything from managing endangered species to contemplating life in extreme extraterrestrial settings.

Scientists are also investigating links between surface and deep ocean ecosystems. While vent communities are independent of sunlight, they're not entirely isolated. Organic matter sinking from the surface provides supplemental nutrition for some vent animals. Deep currents carry vent larvae and potentially deliver them to new habitats. And as mentioned earlier, dissolved metals from vents eventually reach surface waters. The ocean is more interconnected than we once thought, with these alien ecosystems playing an integral role in planetary processes.

The discovery of hydrothermal vent ecosystems fundamentally changed humanity's perspective on life. Before 1977, biology textbooks taught that all ecosystems ultimately depend on the sun. That's true for rain forests, coral reefs, grasslands, and even the polar regions. But it's not universally true. There are exceptions, and they're not small or marginal - they're complex, productive ecosystems covering potentially thousands of square miles of ocean floor.

This realization forced scientists to rethink basic principles. Life doesn't require photosynthesis; it requires energy in some form. Ecosystems don't need to be mild; organisms can adapt to nearly any stable condition. And Earth isn't the only place where such systems could flourish - any world with liquid water and geological activity is a candidate.

For those of us on the surface, going about our sunlit lives, it's humbling to consider that some of Earth's most alien landscapes aren't in distant deserts or frozen tundras but directly beneath our feet, hidden under miles of water. Complete biospheres thrive down there, powered by the planet's heat, adapted to pressures that would crush us, metabolizing chemicals that would poison us, and living lives utterly unlike our own.

They remind us that life is more creative, more resilient, and more widely distributed than we ever imagined. And they whisper a tantalizing possibility: if such alien ecosystems exist in Earth's ocean, what might we find beneath the ice of Europa, in the plumes of Enceladus, or in the subsurface aquifers of Mars? The search for life beyond Earth looks not to the stars but to the dark, pressurized oceans that might lie hidden throughout our solar system and beyond. Down there, in the darkness, life might be waiting.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.