Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Microbial communities in Earth's most extreme acidic hot springs survive 120°C temperatures not through individual toughness, but through cooperative alliances that share resources and build protective biofilms, revealing fundamental insights about life's origins and the search for extraterrestrial organisms.

Deep inside Yellowstone's Norris Geyser Basin, where acidic waters bubble at temperatures that would instantly denature your DNA, something remarkable thrives. Not lone-wolf organisms toughing it out, but entire communities of microbes working together as a living orchestra. These aren't just survivors adapting to harsh conditions - they're redefining what we thought possible for life itself, and they're doing it through cooperation rather than individual resilience.

For decades, scientists assumed extremophiles were solitary warriors, each species independently armored against heat, acid, or radiation. But recent discoveries reveal a far more sophisticated reality. In hot springs reaching 120°C and pH levels as low as 1, microbial consortia share metabolic resources, construct protective biofilms, and collectively withstand stresses that would obliterate any single organism. This partnership model isn't just fascinating biology - it's reshaping our search for alien life and spawning revolutionary biotechnologies.

Walk up to one of these extreme environments and you'll see brilliant colors - oranges, greens, yellows streaking the mineral-encrusted edges of boiling pools. Those vivid hues aren't mineral deposits. They're living microbial mats, layered communities where archaea, bacteria, and even some hardy eukaryotes work in synchronized metabolic networks.

Here's what makes these consortia exceptional: while a single thermophile species might tolerate temperatures between 60°C and 108°C, working together allows communities to push past individual limits. One microbe's waste becomes another's food source. Hydrogen producers partner with hydrogen consumers in a metabolic handshake called syntrophy, making energy extraction possible where it would otherwise fail thermodynamically.

In hot springs reaching 120°C and pH levels around 2 - conditions similar to boiling battery acid - microbial consortia create cooperative networks that enable survival impossible for any individual organism.

Recent research from Frontiers in Microbiology documented consortia in acidic hot springs where temperatures exceed 100°C and pH hovers around 2 - conditions similar to battery acid heated to boiling. Individual species would struggle, but together they create microenvironments within their biofilms that buffer temperature fluctuations and neutralize localized acidity.

The biofilm itself becomes a shared fortress. Microbes secrete extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) - essentially biological glue mixed with protective compounds - that form a matrix around the community. This matrix doesn't just provide structural integrity; it creates chemical gradients that allow different species to occupy distinct niches within millimeters of each other, each optimized for different metabolic roles.

The biochemistry enabling survival at these extremes reads like science fiction. Proteins that would unravel in your body maintain their structure at 120°C through hyperthermophilic adaptations: increased ionic interactions, more compact folding, and amino acid substitutions that create molecular scaffolding resistant to thermal chaos.

But individual adaptations only tell part of the story. In iron oxide microbial mats studied in acidic geothermal springs, researchers found distinct layers forming over time. Early colonizers - often archaea from the genus Sulfolobus - establish a foothold by oxidizing sulfur compounds. Their metabolic byproducts create conditions that allow iron-oxidizing bacteria to move in next. These bacteria, in turn, precipitate iron minerals that provide physical structure for the growing mat.

This succession isn't random. It's a coordinated assembly process where each wave of colonizers engineers the environment for the next, like construction crews preparing a building site. The stratification in these mats creates oxygen gradients, pH microzones, and temperature buffers that expand the range of conditions individual species can tolerate.

"The coordinated assembly of microbial communities in extreme environments shows that cooperation isn't just beneficial - it's thermodynamically necessary for survival above certain temperature and acidity thresholds."

- From research on iron oxide mat succession in acidic springs

Consider Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, a workhorse archaeon thriving in environments with pH 2-3 and temperatures of 75-80°C. Alone, it struggles above 85°C. But within a consortium where methane-producing archaea consume hydrogen that would otherwise inhibit Sulfolobus metabolism, the community can colonize springs approaching 95°C. The partnership expands everyone's viable range.

Four locations serve as natural laboratories for studying these microbial alliances, each offering distinct insights into life's thermal and acidic limits.

Yellowstone's Norris Geyser Basin remains the gold standard, where Thomas Brock's pioneering 1966 discovery of Thermus aquaticus revolutionized molecular biology. But beyond individual species, Yellowstone's acidic hot springs revealed complex community dynamics. The famous Grand Prismatic Spring's rainbow colors represent distinct consortial zones, each dominated by different photosynthetic and chemosynthetic partnerships optimized for specific temperature bands.

Recent metagenomic studies of Yellowstone's extreme environments uncovered unexpected diversity - not just archaea and bacteria, but viruses that infect thermophiles, suggesting complete ecosystems operating above 90°C. These viral communities may regulate population dynamics and facilitate horizontal gene transfer, allowing rapid adaptation to environmental shifts.

Japan's Beppu hot springs offer a different window into microbial cooperation. Studies of Japanese geothermal sites revealed ancient archaeal lineages, including members of the DPANN superphylum - ultra-small archaea with reduced genomes that depend entirely on partnerships with larger host organisms. These aren't parasites; they're symbionts providing metabolic functions their hosts lack, creating obligate mutualism where neither can survive alone.

Iceland's Hveragerði geothermal fields present consortia dealing with rapid environmental fluctuations. Unlike Yellowstone's relatively stable pools, Icelandic systems experience frequent mixing of cold groundwater with superheated geothermal fluids, creating temperature swings of 40°C in hours. The microbial communities here show remarkable resilience through bet-hedging strategies - maintaining dormant populations that can rapidly bloom when conditions shift.

New Zealand's Taupō Volcanic Zone, centered around Lake Taupō, hosts some of the most acidic hot springs on Earth. Springs with pH below 1.5 support consortia dominated by archaeal specialists that metabolize sulfur compounds in networks so tightly coupled that metabolic modeling suggests they function as a single superorganism, sharing resources through coordinated gene expression.

These extreme communities aren't just biological curiosities - they're time machines showing us what early Earth might have looked like.

Four billion years ago, our planet was a hostile place: volcanic activity dominated the landscape, the atmosphere lacked oxygen, and UV radiation battered the surface. The earliest life forms likely emerged in environments similar to modern hot springs, where geothermal chemistry provided energy gradients and minerals catalyzed prebiotic reactions.

The discovery of archaeal viruses with lipid membranes in China's Tengchong acidic hot springs suggests that even early in life's history, multiple domains of life coexisted and interacted. These aren't just bacteria or archaea going it alone - they're entire ecosystems where viruses, archaea, and bacteria exchange genetic material and metabolic products.

If life on Earth began not with individual cells but with communities, the leap from chemistry to biology might have required less improbable luck than we thought. Complex metabolic networks could emerge through division of labor among simple proto-cells.

Genomic analysis of thermophilic consortia reveals something stunning: many fundamental metabolic pathways - including those for carbon fixation and nitrogen cycling - appear to have evolved first in high-temperature environments. The very biochemistry that powers modern cells may have originated through partnerships in ancient hot springs, suggesting cooperation was built into life's foundation from the beginning.

This has profound implications. If life on Earth began not with individual cells but with communities, the leap from chemistry to biology might have required less improbable luck than we thought. Complex metabolic networks could emerge through division of labor among simple proto-cells, each performing one chemical transformation that collectively created self-sustaining cycles.

When NASA scientists design missions to search for extraterrestrial life, they increasingly focus on environments resembling Earth's extreme hot springs. And for good reason - Mars hosted hot springs billions of years ago, and silica deposits there preserve biosignatures similar to those found in Yellowstone.

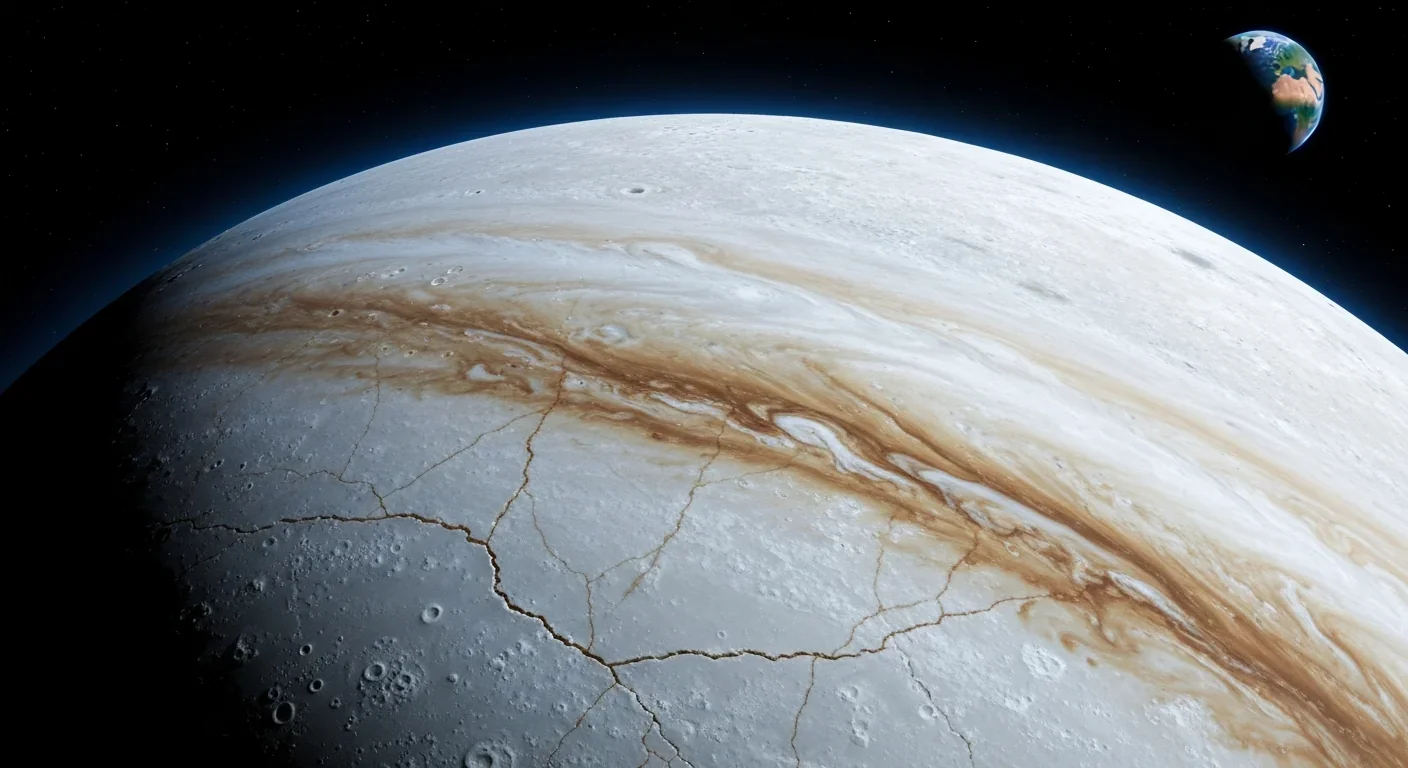

But the real game-changers are ocean worlds: Saturn's moon Enceladus and Jupiter's moon Europa. Both have subsurface oceans in contact with rocky cores, creating hydrothermal vents analogous to Earth's mid-ocean ridge systems. Enceladus spews plumes of ocean water into space, and spectroscopic analysis detects hydrogen, methane, and complex organic molecules - exactly the chemical signatures you'd expect from microbial consortia.

Recent research modeling Europa's ocean chemistry suggests conditions favorable for chemosynthetic communities resembling those in Earth's acidic hot springs. High-pressure environments on Europa may even enhance certain metabolic partnerships, making cooperation not just possible but thermodynamically favorable.

The breakthrough here is conceptual. We're no longer searching for individual organisms tough enough to survive alien environments. We're looking for communities - consortia that collectively create habitable niches through metabolic networking and environmental engineering. This expands the range of conditions we consider potentially life-bearing, because cooperation extends viable ranges far beyond what individual species can tolerate.

Microbes from extreme Earth environments tested under conditions simulating Europa's ocean have survived and even thrived, particularly when grown as mixed communities rather than pure cultures. The implication is clear: if life exists on Europa, it's probably not going it alone.

The practical applications flowing from extreme environment research are transforming multiple industries, and they're worth billions.

Thermostable enzymes top the list. Taq polymerase, extracted from Thermus aquaticus in Yellowstone, became the foundation of PCR technology - the technique that amplifies DNA for everything from crime scene analysis to COVID-19 testing. That single discovery created a multi-billion-dollar industry.

But Taq is just the beginning. Researchers cataloging thermozymes from acidic hot springs have identified DNA polymerases, proteases, lipases, and cellulases that function at extreme temperatures and pH levels. These enzymes enable industrial catalysis at high temperatures without expensive cooling systems, biofuel production where thermostable cellulases break down plant biomass more efficiently than mesophilic enzymes, pharmaceutical synthesis requiring acidic or high-temperature conditions, and detergent formulations where enzymes must withstand hot water and alkaline conditions.

"The discovery of Taq polymerase from Yellowstone hot springs revolutionized molecular biology and created a multi-billion-dollar industry. It's just the first of many biotechnologies emerging from extreme environment research."

- History of PCR technology development

The biotech gold rush extends to bioremediation. Acid mine drainage - one of mining's worst environmental legacies - creates conditions similar to acidic hot springs. Consortia adapted to pH 2 and high metal concentrations can detoxify these environments by precipitating toxic metals as stable minerals, while simultaneously generating electricity through microbial fuel cells.

Biomining applications use thermoacidophilic consortia to extract metals from low-grade ores at a fraction of the energy cost of traditional smelting. Copper and gold mining operations worldwide increasingly employ microbial leaching, where consortia oxidize sulfide minerals to release valuable metals.

Even food production benefits. Heat-stable enzymes from thermophiles improve cheese manufacturing, modify food starches, and create novel textures impossible with conventional enzymes. The glutamate dehydrogenase from hyperthermophiles enables more efficient production of umami-rich flavor compounds.

The upper temperature limit for complex life just got rewritten. In late 2024, researchers discovered a eukaryotic amoeba in California's Lassen Volcanic National Park thriving at 56°C - a full 10°C higher than any previously known complex organism. Named the "fire amoeba," this discovery suggests even eukaryotes with their delicate internal membranes and organelles can evolve extreme heat tolerance.

More remarkably, genomic analysis revealed the amoeba doesn't survive alone. It hosts endosymbiotic bacteria that may provide heat-shock proteins and protective compounds, essentially outsourcing thermal protection through partnership. This mirrors the pattern seen in prokaryotic consortia - cooperation as the key to extreme environment colonization.

Metagenomic surveys of Chinese hot springs published in early 2025 uncovered entirely new archaeal lineages with novel metabolic capabilities, including potential photosynthesis pathways functioning at temperatures above 90°C. If confirmed, this would rewrite textbooks about the temperature limits for phototrophy.

Meanwhile, studies of hydrothermal vents - the deep-sea cousins of hot springs - found microbial consortia functioning at 122°C, the current temperature record for life. These communities near seafloor smoker chimneys create entire ecosystems supporting tubeworms, crustaceans, and fish in pitch-black environments powered entirely by chemical energy.

Why does cooperation work so well in extreme environments? The answer lies in metabolic efficiency and risk distribution.

Thermodynamic constraints make certain reactions impossible for individual organisms. Hydrogen production, for example, is endergonic (energy-consuming) unless hydrogen concentrations stay extremely low. In syntrophic partnerships, hydrogen-consuming organisms keep concentrations low enough that hydrogen-producing partners can complete their metabolism. Neither could survive alone, but together they thrive.

When conditions get extreme, cooperation becomes not just beneficial but thermodynamically essential. The fittest organisms are those best at forming productive partnerships, not those most individually resilient.

Gene sharing through horizontal transfer allows consortia to rapidly acquire adaptive traits. In extreme environments where mutation rates run high due to DNA damage from heat and acidity, sharing beneficial genes through plasmids and viral vectors means useful adaptations spread through the community rather than being locked in single lineages.

Environmental buffering through biofilm construction creates stable microenvironments even when bulk conditions fluctuate wildly. Measurements inside thick microbial mats show temperature variations of just 5°C when the surrounding water swings by 30°C, and pH differences of 1-2 units across millimeter scales within the biofilm.

Functional redundancy provides resilience. If one species in the consortium dies off due to environmental stress, others with overlapping metabolic capabilities can compensate until conditions improve and diversity rebounds. This creates ecosystem stability impossible for single-species populations.

These microbial alliances fundamentally challenge how we define life and predict where we'll find it.

Traditional biology focuses on individual organisms - their genetics, metabolism, reproduction. But consortial systems blur those boundaries. When metabolic pathways are distributed across species, when survival depends absolutely on community presence, when genetic exchange is routine rather than rare, the "organism" becomes the consortium itself.

This matters for astrobiology because it means biosignatures might not come from individual species but from community-level metabolic networks. On Mars or Europa, we shouldn't just look for single organisms adapted to harsh conditions. We should look for chemical signatures of coupled metabolic processes, mineral deposits suggesting biofilm formation, and geochemical gradients indicating environmental engineering by microbial communities.

It also reframes evolutionary theory. Darwin's "survival of the fittest" typically emphasizes competition, but in extreme environments, cooperation often trumps competition. The fittest organisms are those best at forming productive partnerships, not those most individually resilient. This suggests that as conditions get harsher, life becomes more social, not less.

Several frontiers promise breakthrough discoveries in the coming years.

Single-cell genomics now allows sequencing individual microbes from consortia without lab cultivation, revealing the genetic blueprints of organisms we can't grow in isolation. This technology is exposing vast microbial "dark matter" - lineages known only from DNA sequences, including likely symbiotic species that may have never existed as free-living organisms.

Metabolomics tracks the chemical compounds flowing through consortial networks in real-time, mapping exactly who produces what and who consumes it. These chemical network maps reveal emergent properties impossible to predict from genomic data alone.

Synthetic consortia designed in labs test principles learned from natural communities. Engineers are building artificial microbial partnerships optimized for specific industrial tasks, like converting waste carbon dioxide into biofuels or producing pharmaceutical compounds through division of labor.

Deep biosphere exploration in subsurface hot aquifers is uncovering consortia living kilometers underground, disconnected from surface productivity for millions of years. These communities suggest that Earth's biomass may be far larger than surface-based estimates, with most of it existing in deep, hot environments we've barely begun to explore.

The story of microbial consortia in boiling acid isn't just academic curiosity - it has direct relevance to how we understand resilience, cooperation, and survival in harsh conditions.

These communities demonstrate that the toughest environments don't breed lone survivors; they breed partnerships. When conditions get extreme, cooperation becomes not just beneficial but essential. That principle applies beyond microbiology to social systems, business organizations, and even global challenges like climate change.

The technologies emerging from extremophile research are already in your life. PCR-based diagnostics, industrial enzymes, biofuels - all trace back to organisms discovered in places life supposedly couldn't exist. As we push deeper into extreme environment exploration, expect more breakthroughs that seem like science fiction until they're everyday tools.

And the astrobiology implications are profound. We're not alone in thinking that life, if it exists elsewhere, probably isn't facing those challenges solo. The discovery of biosignatures on Mars or ocean worlds would likely reveal communities, not individuals - partnerships that make the improbable possible.

Perhaps the deepest insight from these microbial alliances is philosophical. Life's most remarkable achievement isn't individual toughness against hostile conditions. It's the ability to form partnerships that collectively transcend what any individual could achieve.

In Yellowstone's boiling, acidic cauldrons, in Japanese hot springs, in Icelandic geothermal fields, and in New Zealand's volcanic zones, microbes demonstrate daily that cooperation isn't a luxury for when times are easy. It's a survival strategy for when times get hard.

These ancient partnerships, operating at the limits of chemistry and physics, may represent life's most fundamental mode. Not organisms eking out existence against the odds, but communities engineering their own survival through metabolic networking and environmental transformation.

That's the real revolution in extremophile research: recognizing that life's upper limits are set not by individual tolerance, but by collective innovation. When hell becomes home, you don't go it alone.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.