Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Scientists discovered fungi thriving in Chernobyl's radioactive ruins that convert deadly gamma radiation into usable energy through melanin pigments. These organisms could revolutionize space travel radiation shielding and nuclear cleanup.

Imagine a world where the deadliest force known to humanity becomes food. That world already exists, thriving on the radioactive ruins of our greatest nuclear disaster.

In the early 1990s, robots sent into Chernobyl's destroyed reactor discovered something extraordinary: black fungal growths colonizing the most radioactive areas of the building's interior. Not merely surviving the lethal radiation, these organisms appeared to be drawn to it, growing toward the source like plants reaching for sunlight. It was the first hint that some life forms might not just tolerate radiation but actually benefit from it.

This discovery launched what would become one of biology's most fascinating investigations. Scientists identified over 200 species of fungi in and around Chernobyl, many heavily pigmented with melanin. The same molecule that gives color to human skin appeared to have a completely different function in these organisms: converting deadly gamma rays into usable energy.

The 1986 Chernobyl explosion created Earth's largest unintentional laboratory for studying life under extreme radiation. When scientists finally accessed the reactor's interior, they expected to find a biological wasteland. Instead, they found a thriving ecosystem adapted to conditions that would be instantly fatal to most organisms.

The fungi weren't hiding from radiation or armoring themselves against it. They were actually growing toward it, displaying what researchers called "positive radiotropism" - directional growth toward radiation sources. This behavior mirrored the way plants grow toward light, suggesting fungi might be using radiation the same way plants use photons.

When gamma rays struck melanin molecules in fungal cell walls, measurable shifts occurred in their electron spin resonance signals - evidence that the pigment was absorbing and transforming radiation into potentially usable energy.

But the real breakthrough came in 2007, when Dr. Ekaterina Dadachova and her team at Albert Einstein College of Medicine published a landmark study in PLOS ONE. They exposed melanized fungi to radiation levels 500 times normal background and watched something remarkable happen. Cryptococcus neoformans, a common fungal species, grew three times faster than unexposed controls. The fungi weren't just tolerating radiation; they were thriving on it.

The study demonstrated that ionizing radiation fundamentally changed melanin's electronic properties. When gamma rays struck melanin molecules in fungal cell walls, measurable shifts occurred in their electron spin resonance signals. The pigment was absorbing radiation and transforming it, potentially creating an electron flow that could be coupled to metabolic processes.

This was radiosynthesis - a form of energy harvesting distinct from anything previously observed in biology.

To understand how these fungi work, we need to look at melanin itself. This ancient pigment appears across all kingdoms of life, with fossil specimens dating back over 160 million years. It protects our skin from UV damage, gives feathers and fur their color, and shields organisms from environmental stresses.

But in radiotrophic fungi, melanin plays a dramatically different role. The proposed mechanism involves radiation absorption triggering changes in melanin's electronic structure. High-energy gamma rays knock electrons into excited states, creating a cascade effect that could generate usable chemical energy.

Think of it as a biological solar panel, but instead of visible light, it harvests the electromagnetic spectrum's dangerous end. Where chlorophyll in plants captures photons to drive photosynthesis, melanin in these fungi appears to capture gamma rays to drive radiosynthesis. The fundamental principle is similar: convert environmental radiation into chemical bonds that power cellular processes.

"Radiotrophic fungi could serve as a food supply and source of radiation protection for interplanetary astronauts, who would be exposed to cosmic rays."

- Dr. Ekaterina Dadachova, Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Three species have become the focus of intensive study. Cladosporium sphaerospermum thrives in the most contaminated zones of Chernobyl and has become the primary candidate for space applications. Cryptococcus neoformans, though capable of causing human disease, demonstrated the most dramatic growth enhancement under radiation in laboratory experiments. Wangiella dermatitidis rounds out the trio, showing robust melanin-mediated radiation responses.

The leap from Chernobyl to space might seem unexpected, but radiation presents one of the biggest obstacles to deep-space exploration. Beyond Earth's protective magnetic field, cosmic rays bombard everything continuously. Astronauts on a Mars mission would be exposed to radiation levels that dramatically increase cancer risk and could cause acute radiation sickness during solar storms.

Traditional shielding uses heavy metals or thick layers of water, adding massive weight to spacecraft. Every kilogram launched into orbit costs thousands of dollars. A biological shield that could grow and repair itself represented an elegant alternative.

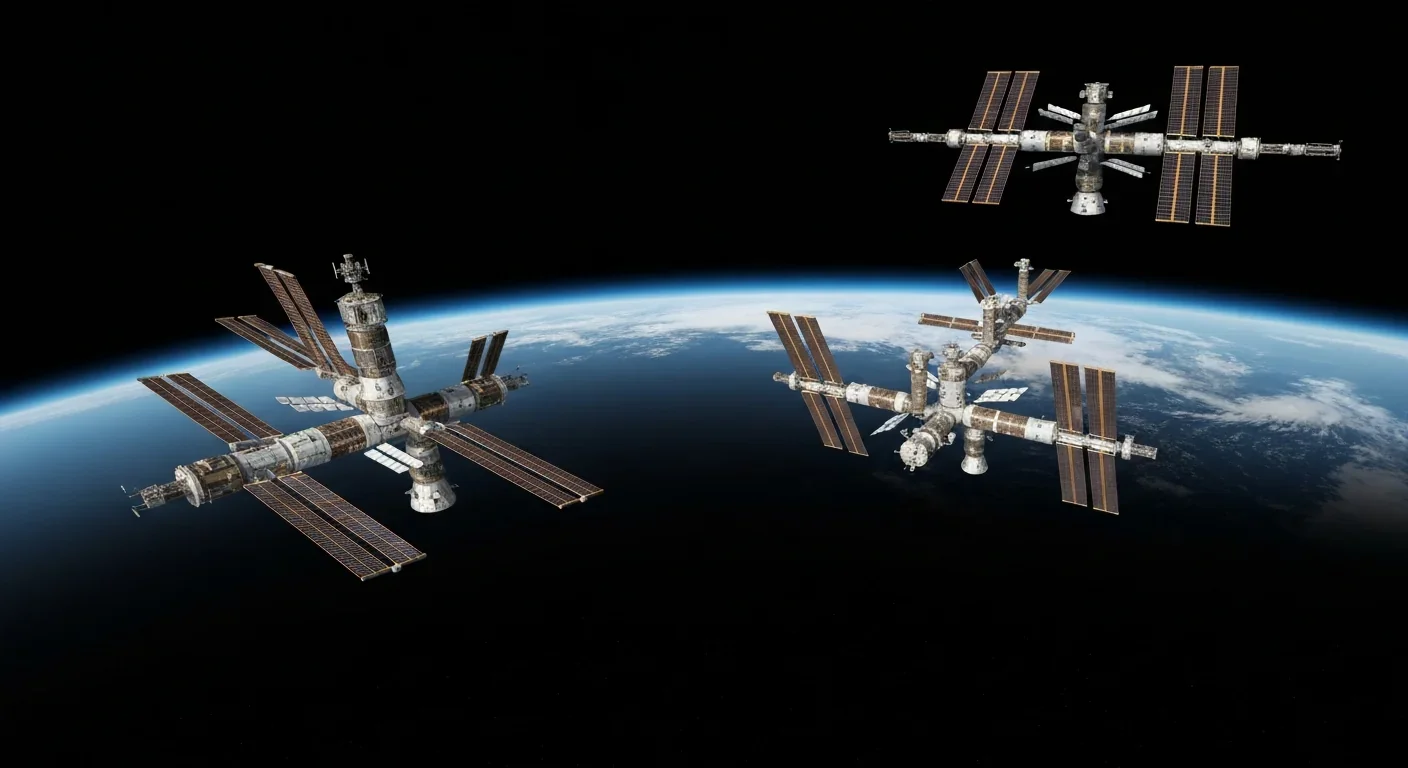

In 2018, NASA sent Cladosporium sphaerospermum to the International Space Station to test this possibility. Over a 26-day experiment simulating Martian surface conditions, researchers grew fungal cultures in microgravity and measured their radiation-blocking capabilities.

The results were modest but promising: a thin fungal layer reduced cosmic radiation by approximately 2% compared to control areas. That might not sound impressive, but it came from a layer just a few centimeters thick, weighing almost nothing, and capable of regenerating if damaged. Scale it up to the proposed 21-centimeter biological shield, and you could achieve meaningful protection without the crushing weight penalty of conventional materials.

A self-repairing, self-growing radiation shield cultivated on spacecraft could provide meaningful protection without the massive weight penalty of conventional materials - a game-changer for deep-space missions.

Even better, the fungi grew faster in space than on Earth. The microgravity environment combined with radiation exposure appeared to create ideal conditions for fungal expansion. A self-repairing, self-growing radiation shield could be cultivated on spacecraft using minimal resources.

Not everyone agrees these fungi are truly "eating" radiation. The scientific community remains divided on whether we're witnessing genuine radiosynthesis or something more subtle.

Skeptics point out that radiation's energy content is relatively low compared to sunlight. Even in Chernobyl's hottest zones, the total energy available from gamma rays pales against what plants harvest from a sunny day. Could melanin really extract meaningful metabolic benefit from such a diffuse energy source?

The alternative explanation suggests radiation might trigger protective pathways that coincidentally enhance growth. Perhaps gamma rays damage competing organisms or break down organic materials into simpler nutrients fungi can absorb more easily. The growth advantage might be indirect rather than the result of true energy harvesting.

Supporting the radiosynthesis hypothesis, however, is the directional growth toward radiation sources. Fungi don't just tolerate high-radiation zones; they actively seek them out. This behavior suggests they're detecting and responding to radiation as a resource, not merely as a stress to be endured.

The measurable changes in melanin's electronic properties also point toward genuine energy harvesting. Electron spin resonance shifts indicate real physical transformations occurring when radiation strikes melanin molecules. The question is whether fungi can couple these changes to useful metabolic work.

A 2014 patent filed by Dadachova and colleagues proposed methods for increasing melanization to enhance fungal growth under radiation. The patent's existence suggests researchers believe the effect is real and exploitable, though patents alone don't constitute scientific proof.

The truth likely lies somewhere between the extremes. Radiotrophic fungi probably do extract some energy from radiation, but perhaps not as their primary energy source. Think of it as a supplementary power system, useful in high-radiation environments but not replacing conventional metabolism entirely.

While Chernobyl remains the best-studied site for radiotrophic fungi, they're not unique to Ukraine. Similar organisms have been found at Fukushima following the 2011 disaster, though research there faces different contamination patterns and access restrictions. The consistency across nuclear accident sites suggests radiotrophy is a widespread adaptation rather than a lucky mutation specific to one location.

This raises intriguing questions about where else these organisms might thrive. High-altitude environments receive elevated cosmic radiation. Certain geological formations concentrate natural radioactive elements. Could radiotrophic fungi inhabit these niches too, using radiation that would challenge most organisms?

"The fungal hyphae grew towards the source of ionizing radiation (just the way plants grow towards sunlight showing phototropism)."

- Field observations at Chernobyl

The astrobiology implications are even more speculative but fascinating. If life can harvest energy from ionizing radiation on Earth, could similar organisms exist on worlds with no sunlight but abundant radiation? Jupiter's moon Europa, for instance, sits inside the planet's intense radiation belts. Beneath its ice shell, a subsurface ocean might harbor ecosystems powered not by the sun but by radiation from space.

Mars presents a more immediate possibility. The planet's thin atmosphere offers little protection from cosmic rays, creating surface radiation levels that would quickly kill unprotected humans. But for organisms that view radiation as food rather than danger, Mars might be a paradise.

The potential applications of radiotrophic fungi extend far beyond space exploration. Nuclear cleanup represents an immediate terrestrial use. Contaminated sites around the world need remediation, often at enormous cost using conventional methods. Fungi that thrive in high-radiation zones could be engineered to concentrate radioactive materials, extract them from soil, or simply stabilize contamination by binding it in fungal biomass.

Some species already show promise for bioremediation. By encouraging fungal growth in contaminated zones, cleanup operations could harness natural processes rather than relying solely on mechanical removal or chemical treatment. The fungi would do the work of seeking out and concentrating radioactive materials, potentially making them easier to collect and dispose of safely.

Energy harvesting represents a more speculative but tantalizing possibility. If melanin can genuinely convert radiation into usable chemical energy, could it be scaled up? Imagine biological panels that transform the radiation waste from nuclear reactors into electricity. Even low efficiency might be worthwhile if the fuel source is otherwise dangerous waste.

The 2014 patent for enhancing melanization hints at this direction. By increasing the amount of melanin in fungal cells, researchers hope to boost their radiation-harvesting capacity. Whether this leads to practical energy devices or remains a laboratory curiosity depends on solving significant engineering challenges.

Radiation medicine might also benefit. Cancer treatment uses targeted radiation to destroy tumors, but protecting healthy tissue from collateral damage remains difficult. Could melanin-based compounds shield normal cells while allowing radiation to reach cancer? The same melanin properties that enable fungal growth might be adapted for protective applications in humans.

Research into radiotrophic fungi continues to accelerate. The ISS experiments demonstrated proof of concept for biological radiation shields, but optimizing fungal strains for space applications requires further work. Which species perform best in microgravity? How thick must fungal layers be to provide meaningful protection on a Mars mission? Can fungi be cultivated using Martian regolith and minimal water imports?

Understanding the precise biochemical mechanism remains a priority. How exactly does melanin couple radiation absorption to metabolic processes? What electron transport pathways are involved? Answering these questions could enable bioengineering efforts to create optimized variants with enhanced radiation-harvesting capabilities.

The debate over true radiosynthesis versus radiation tolerance will only be settled by detailed mechanistic studies. Tracking energy flow from gamma ray impact through melanin transformation to ATP synthesis would provide definitive evidence. Such experiments are technically challenging but not impossible with modern biochemical tools.

Astrobiological searches could also incorporate lessons from radiotrophic fungi. If we're looking for life on high-radiation worlds, we should consider organisms that might use that radiation rather than shelter from it. Detection strategies assuming photosynthesis as life's energy base might miss entirely different forms of metabolism.

The black mold growing on Chernobyl's reactor walls represents more than a scientific curiosity - it's a glimpse of biology's ultimate flexibility, life's ability to find advantage in the most unlikely places.

On a philosophical level, radiotrophic fungi remind us that life's ingenuity exceeds our expectations. We classify radiation as dangerous, deadly, something to be avoided and shielded against. These organisms see it as opportunity, a resource to be harvested in environments where little else can survive. They thrive in humanity's worst disasters, turning our mistakes into meals.

The black mold growing on Chernobyl's reactor walls represents more than a scientific curiosity. It's a glimpse of biology's ultimate flexibility, life's ability to find advantage in the most unlikely places. As we venture deeper into space and grapple with nuclear contamination on Earth, these humble fungi might provide solutions we never imagined.

In Chernobyl's exclusion zone, where life should have been extinguished, fungi feast on the very force that drove humans away. They're living proof that one organism's catastrophe can be another's buffet. And in that peculiar resilience lies potential to protect astronauts billions of kilometers from Earth, clean up contaminated soil, and expand our understanding of where and how life can exist.

The future of space exploration might not depend on titanium shields or lead-lined walls, but on cultivating the right mold. And the key to cleaning up nuclear disasters might lie not in bulldozers and concrete, but in encouraging the organisms already flourishing in those forbidden zones.

Sometimes the most powerful solutions come from the places we least expect, growing quietly in the dark, feeding on our fears.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.