Nature's First Farmers: 50 Million Years of Ant Agriculture

TL;DR: Scientists have discovered lichens living inside Antarctic rocks that survive extreme cold, radiation, and desiccation - conditions remarkably similar to Mars. These cryptoendolithic organisms grow just micrometers per year, can live for thousands of years, and have remained metabolically active in Martian simulations, offering profound insights into life's limits and the potential for extraterrestrial biology.

Picture yourself standing on Mars. Not the hypothetical Mars we might colonize someday, but the actual red planet right now - frozen, airless, blasted by radiation. Now picture life thriving there anyway. Impossible? Maybe not, because scientists have found organisms on Earth doing exactly that, and they're not hiding in some protected cave or buried deep underground. They're living inside rocks, in Antarctica's McMurdo Dry Valleys, the closest thing our planet has to the Martian surface.

These organisms, called cryptoendolithic lichens, represent one of nature's most audacious survival strategies. They're photosynthetic life forms that have colonized the interior of translucent rocks, where they endure temperatures that plunge to -60°C, radiation levels that would sterilize most surfaces, and months without a drop of water. They grow slower than almost anything alive - sometimes just 10 micrometers per year - and can live for thousands of years. Their existence challenges our understanding of where life can persist, and their potential parallels to Martian organisms have made them a cornerstone of astrobiology research.

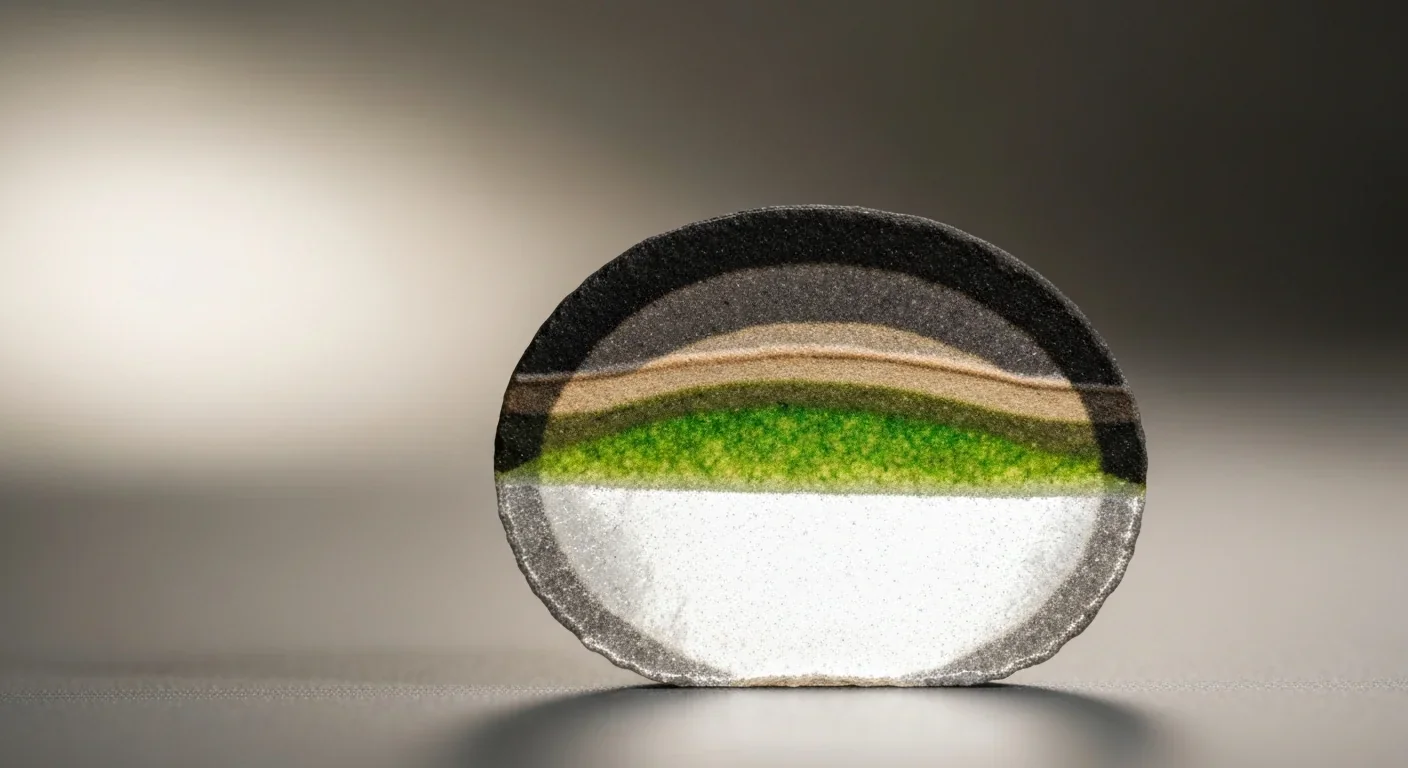

The McMurdo Dry Valleys cover about 4,800 square kilometers of ice-free terrain in Antarctica, where precipitation is so rare that some areas haven't seen liquid water in millions of years. With winds exceeding 320 km/h and average temperatures around -20°C, the valleys are among Earth's harshest deserts. Yet if you crack open certain sandstone rocks here, you'll find bands of green, yellow, and black - living communities of lichens, algae, fungi, and bacteria that have carved out an existence between mineral grains.

These cryptoendolithic (literally "hidden within rock") organisms dominate the biomass in the Dry Valleys. According to research published in the International Journal of Astrobiology, these lichens inhabit up to 100% of sandstone cliffs and 30% of granite boulders in the region. They're not a curiosity - they're the main show, the primary life form in one of Earth's most extreme ecosystems.

The species found here belong to several lichen families, with Diploschistes muscorum and Cetraria aculeata among the most resilient. Lichens themselves are composite organisms, symbiotic partnerships between fungi (which provide structure and protection) and photosynthetic partners like algae or cyanobacteria (which produce food through photosynthesis). This dual nature gives them remarkable flexibility in extreme environments, but cryptoendolithic lichens take it further by abandoning the surface entirely.

Living inside rock might seem like an odd survival strategy, but for these organisms, it's brilliant engineering. The translucent sandstone and granite they colonize filters out 99% of harmful UV radiation while allowing enough visible light through for photosynthesis. The rock also provides thermal insulation, buffering against the valley's wild temperature swings, and creates a microenvironment where moisture from snow or fog can be retained for brief periods.

The rocks themselves are carefully selected by evolution. Studies show that weathered sandstone and granite allow sufficient light penetration for photosynthetic pigments to function in subsurface strata. The lichens typically colonize the rock in distinct layers: melanized black fungi form the outermost layer, providing an additional UV screen, while the green photosynthetic layer sits beneath, followed by a white fungal layer that may reflect light back upward to maximize energy capture.

Cryptoendolithic lichens grow just 1-10 micrometers per year - so slowly that some colonies are estimated to be 10,000 years old, making them among Earth's longest-lived organisms.

This architectural precision allows the lichens to operate on incredibly low energy budgets. They're active only when conditions permit - perhaps a few hours per year when temperature, light, and moisture align. The rest of the time, they remain in metabolic suspension, their cells frozen but intact, waiting for the next brief window of opportunity.

How do these organisms survive conditions that would kill most life within minutes? The answer involves multiple layers of biological innovation, some of which scientists are only beginning to understand.

Freeze-Thaw Mastery: Antarctic cryptoendolithic lichens regularly experience temperature swings from -60°C to +15°C. Each freeze-thaw cycle creates ice crystals that can puncture cell membranes, but these lichens have evolved specialized cell wall structures and antifreeze proteins that prevent ice formation inside cells. When they do freeze, they produce protective compounds called cryoprotectants that stabilize cellular machinery.

Desiccation Tolerance: Perhaps more impressive than cold tolerance is their ability to survive complete desiccation. These lichens can lose virtually all cellular water and remain dormant for months or even years. When water returns - from snow, fog, or rare precipitation - they rehydrate and resume metabolism within hours. This capacity for cryptobiosis (suspended animation) is rare among photosynthetic organisms.

Radiation Resistance: UV radiation is particularly destructive to DNA, yet these lichens have developed multiple defenses. The melanin pigments in their outer fungal layers absorb UV before it reaches sensitive cellular machinery. Additionally, recent research has revealed that cryptoendolithic lichens possess enhanced DNA repair mechanisms and produce protective pigments that neutralize radiation damage.

Atmospheric Chemosynthesis: One of the most surprising discoveries is that these communities don't rely entirely on photosynthesis. Recent metagenomic analysis revealed over 2,600 novel prokaryotic species within the lichen communities, many possessing high-affinity hydrogenases that can extract energy from atmospheric hydrogen. This atmospheric chemosynthesis provides a backup energy source when conditions are too dark or dry for photosynthesis - a strategy that could be critical for life on other planets.

When NASA scientists began searching for locations on Earth that resemble Mars, the McMurdo Dry Valleys topped the list. Both environments share key characteristics: extreme cold, hyper-aridity, intense UV radiation, rapid temperature fluctuations, and minimal organic matter. If life could exist on Mars today, it would likely resemble the cryptoendolithic communities of Antarctica.

This parallel has made these lichens prime candidates for astrobiology experiments. In one landmark study, European scientists placed Antarctic cryptoendolithic fungi on the International Space Station, exposing them to simulated Martian conditions for 18 months: Mars-like atmospheric composition, vacuum, UV radiation, and temperature extremes. The results were stunning: more than 60% of fungal cells remained intact with stable DNA. The lichens exposed to Martian atmosphere actually showed double the metabolic activity compared to those exposed only to space vacuum - suggesting that Mars-like conditions might not just permit survival but could potentially enhance certain metabolic processes.

"Our study is the first to demonstrate that the metabolism of the fungal partner in lichen symbiosis remained active while being in an environment resembling the surface of Mars."

- Kaja Skubała, lead researcher

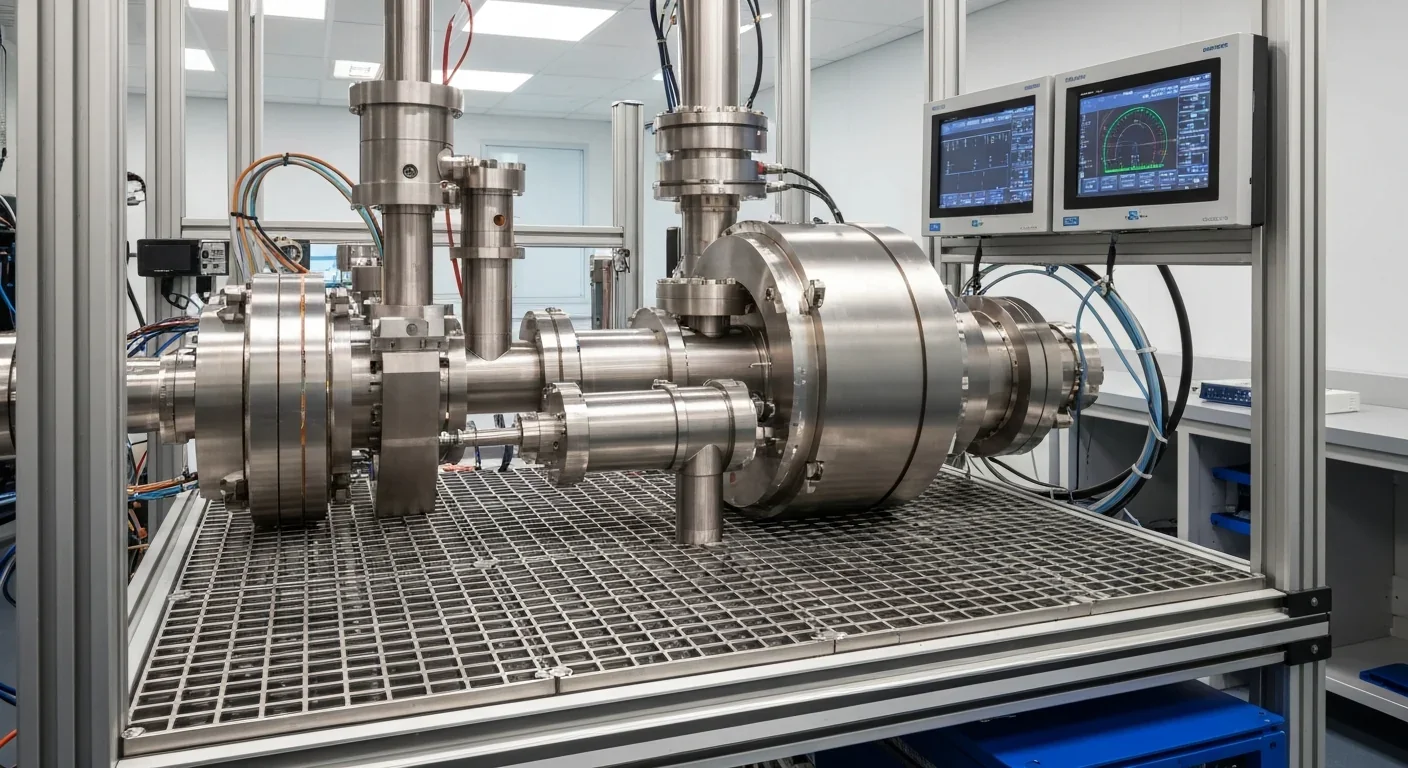

More recently, a 2025 study subjected Diploschistes muscorum and Cetraria aculeata to a five-hour Mars simulation in a vacuum chamber with CO₂-rich atmosphere, low pressure, temperature fluctuations, and X-ray radiation equivalent to one year of solar activity on Mars. Lead researcher Kaja Skubała reported that the fungal partners maintained active metabolism and invoked defense mechanisms, particularly increased melanin deposition. "Our study is the first to demonstrate that the metabolism of the fungal partner in lichen symbiosis remained active while being in an environment resembling the surface of Mars," Skubała noted.

The CRYPTOMARS project, a multi-omic research initiative, is taking this further by subjecting Antarctic rock samples to 15 Gray of gamma radiation while maintaining them at temperatures and humidity levels that simulate Martian surface conditions. The project integrates genomic, metabolomic, and lipidomic analysis to understand not just whether these organisms can survive, but how their metabolic pathways adapt to Martian-analog stress.

These experiments aren't just academic exercises. If cryptoendolithic organisms can remain viable under Martian conditions, it raises profound questions about whether similar life forms could have evolved on Mars during its wetter past - or whether they might persist there today, hidden within rocks much as they are in Antarctica.

One of the most remarkable aspects of cryptoendolithic lichens is their relationship with time. These organisms grow at rates that make glaciers look speedy. Research indicates that lichen colonies expand only 1 to 10 micrometers per year - roughly the width of a red blood cell. At this pace, it takes millennia to colonize a rock face.

Age estimates for some Antarctic cryptoendolithic communities run to 10,000 years or more. These aren't individual organisms living that long (though the fungal partners may persist for centuries), but continuous communities that have maintained themselves across hundreds of generations. The turnover is so slow that researchers studying cell division in some endolithic microorganisms estimate it occurs only once every hundred years, with some deep-sea endoliths potentially reproducing only once every 10,000 years.

This extreme longevity makes cryptoendolithic lichens valuable as climate archives. Because they grow so slowly and are so sensitive to environmental conditions, changes in their distribution or health can signal shifts in Antarctic climate that might otherwise go unnoticed. They're living sensors, recording decades or centuries of environmental history in their tissues.

As the planet warms, Antarctica is changing faster than almost anywhere else. The western Antarctic Peninsula has warmed by about 3°C over the past 50 years - five times the global average. While much attention focuses on melting ice sheets and threatened penguin colonies, cryptoendolithic lichens offer a different window into climate change: they reveal how warming affects the driest, coldest terrestrial ecosystems on Earth.

These organisms exist at the absolute edge of where photosynthetic life can survive. Small temperature increases can shift that edge, expanding habitable zones in some areas while threatening communities in others. Increased temperature variability - more frequent freeze-thaw cycles - can actually harm these lichens despite their cold tolerance, because metabolic activity increases energy expenditure without necessarily increasing growth opportunities.

When exposed to simulated Martian conditions on the ISS, cryptoendolithic lichens showed double the metabolic activity compared to space-only exposure - suggesting Mars-like atmospheres might actually enhance their survival.

Scientists monitoring Antarctic cryptoendolithic communities have documented changes in distribution patterns over recent decades. Some rock faces that once supported dense lichen populations now show signs of stress or abandonment. Others, previously too cold for colonization, are now being occupied. These shifts happen slowly by human standards, but they're rapid by lichen time, suggesting significant environmental disruption.

The implications extend beyond Antarctica. If climate change can stress organisms that have survived millions of years in Earth's harshest environments, it raises questions about the resilience limits of ecosystems everywhere. These lichens survived the last glacial maximum 20,000 years ago, when global temperatures were 5-6°C cooler than today. They endured the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age. But current warming is occurring at a pace unprecedented in their evolutionary history, and even extremophiles have limits.

The study of cryptoendolithic lichens forces us to reconsider fundamental questions about life's requirements. Textbooks teach that life needs water, energy, nutrients, and moderate conditions. These organisms show that "moderate" is relative, and that life can operate on energy and water budgets so minimal they approach the theoretical limits of metabolism.

Several key insights emerge from decades of research on these organisms:

Life Adapts to Available Energy: In the McMurdo Dry Valleys, cryptoendolithic lichens receive perhaps a few hours per year of conditions suitable for active metabolism. Yet they persist, demonstrating that life can function on astonishingly low power. This has implications for understanding potential biospheres on ocean worlds like Europa or Enceladus, where energy may be even more scarce.

Community Matters: These aren't isolated organisms but complex communities where fungi, algae, bacteria, and even viruses interact. The CRYPTOMARS research emphasizes that community-level interactions - nutrient sharing, metabolic complementarity, collective stress responses - enable survival that individual species couldn't achieve alone. This suggests that life in extreme environments may necessarily be communal.

Physical Protection Is Critical: The rock itself is not just habitat but active protection, filtering radiation, buffering temperature, and retaining moisture. This principle - that life in hostile environments requires physical refugia - guides the search for life on other worlds. On Mars, we shouldn't just look at exposed surfaces but within rocks, beneath regolith, and in any structure that offers protection.

Time Operates Differently: For organisms that reproduce once per century and grow 10 micrometers per year, evolutionary and ecological processes operate on vastly different timescales than what we observe in temperate ecosystems. This challenges our assumptions about how quickly life can adapt and what constitutes a viable population. A "successful" cryptoendolithic population might change imperceptibly across human lifetimes yet be undergoing rapid evolution on its own temporal scale.

Since the 1970s, scientists have made regular expeditions to the McMurdo Dry Valleys to study cryptoendolithic communities. These research programs have evolved from simple surveys to sophisticated multi-omic studies integrating genomics, metabolomics, and environmental monitoring.

Field research here is challenging. The environment that makes these lichens interesting - extreme cold, high winds, remoteness - also makes them difficult to study. Scientists must work in protective gear, using techniques that don't damage the delicate rock communities. Samples collected are often stored frozen to preserve metabolic states, then analyzed in labs around the world using cutting-edge molecular techniques.

"Cryptoendolithic communities are the main standing biomass in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, occupying approximately 4% of sandstone boulders and up to 100% of sandstone cliffs."

- Pointing et al., 2009

Recent survey expeditions have expanded beyond Antarctica. At the Mars Desert Research Station in Utah and the Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station in Nunavut, researchers have conducted simulated Mars missions, with crew members in spacesuits collecting over 150 lichen specimens representing 48 taxa. These analog studies help refine techniques for potential Mars sample return missions while building a database of extremophile biodiversity.

The work combines multiple disciplines: microbiology, geology, atmospheric science, astrobiology, climate science, and even planetary protection (ensuring Earth organisms don't contaminate Mars). This interdisciplinary approach reflects the complexity of cryptoendolithic ecosystems and their relevance to multiple fields.

As humanity contemplates becoming a multi-planet species, organisms like cryptoendolithic lichens take on new significance. They demonstrate that life can persist in environments previously considered uninhabitable, using strategies we're only beginning to understand.

Some researchers are exploring whether engineered extremophiles could help terraform Mars or sustain life support systems on long space missions. The atmospheric chemosynthesis discovered in Antarctic lichen communities, for instance, suggests that organisms could potentially extract energy from Martian atmosphere if augmented with the right metabolic pathways. The radiation-resistance mechanisms - melanin production, enhanced DNA repair, cryptobiosis - might be transferable to other organisms or inform protective technologies for astronauts.

There's also value in simply understanding these organisms as proof of concept. If life arose independently on Mars, it likely faced similar selective pressures that shaped Antarctic cryptoendoliths: intense radiation, temperature extremes, water scarcity, thin atmosphere. Studying Earth's rock dwellers gives us a template for recognizing potential Martian biosignatures - the chemical, physical, or biological markers that might indicate past or present life.

Metagenomic analysis revealed over 2,600 novel prokaryotic species within cryptoendolithic communities, many capable of atmospheric chemosynthesis - extracting energy from hydrogen in the air when photosynthesis isn't possible.

But perhaps the most profound lesson from these lichens is about perspective. They remind us that "extreme" is subjective. For organisms that evolved in Antarctic rocks, those conditions aren't extreme - they're normal. The temperature fluctuations, radiation exposure, and moisture scarcity that would kill us within hours are, to them, just another day. This reframes how we think about habitability. Rather than asking whether an environment can support life as we know it, we should ask: what forms of life might that environment support?

Standing in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, the landscape appears utterly barren - endless expanses of rock, gravel, and ice beneath a sky so dry that precipitation virtually never falls. It's easy to imagine you're alone, surrounded by lifelessness. But crack open a rock, and suddenly you're looking at a thriving community millions of years in the making, organisms that have been here far longer than our species has existed, living lives of such patient persistence that they make tortoises look impatient.

These are not the charismatic megafauna that usually capture public imagination. There are no dramatic photos of cryptoendolithic lichens hunting prey or migrating across continents. They don't have expressive faces or complex social behaviors. They're invisible to casual observation, silent, and stationary. Yet in their own way, they're as remarkable as any organism on Earth - perhaps more so, because they show us just how tenacious, how creative, how improbably stubborn life can be when given even the slightest foothold.

Climate scientists monitoring the Antarctic ice sheets, astrobiologists designing Mars missions, evolutionary biologists studying adaptation - all find themselves returning to these humble rock dwellers. They're reference points, living experiments that have been running for millennia, natural laboratories that test the limits of biology with a rigor no human experiment could match.

As we face our own planetary challenges - a changing climate, questions about whether we're alone in the universe, uncertainties about life's resilience in the Anthropocene - these organisms offer both warning and inspiration. They warn us that even life adapted to extremes can be pushed past its limits if change comes too fast. And they inspire us by demonstrating that life, given time and opportunity, can find ways to persist in places we'd never imagine looking.

In the end, cryptoendolithic lichens are survivors in the truest sense. Not because they're tough or aggressive, but because they're patient, efficient, and exquisitely adapted to their niche. They don't fight their environment - they inhabit it so completely, so cleverly, that what looks like bare rock is actually a home, a community, a thriving ecosystem hidden in plain sight.

If we ever find life on Mars, it might look a lot like this: invisible to a casual glance, living inside rock, growing impossibly slowly, existing at the very edge of what thermodynamics allows. And when we crack that Martian rock open - if we're lucky enough, careful enough, thoughtful enough - we'll see bands of color in the stone, and we'll know we've found our neighbors.

We'll know we're not alone after all.

Triton, Neptune's largest moon, orbits backward at 4.39 km/s. Captured from the Kuiper Belt, tidal forces now pull it toward destruction in 3.6 billion years.

Banned pesticides like DDT persist in food chains for decades, concentrating in fatty fish and dairy products, then accumulating in human tissues where they disrupt hormones and increase health risks.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

Humans systematically overestimate how single factors affect future happiness while ignoring broader context - a bias called the focusing illusion. This cognitive flaw drives poor decisions about careers, purchases, and relationships, and marketers exploit it ruthlessly. Understanding this bias and adopting systems-based thinking can improve decision-making, though awareness alone doesn't eliminate the effect.

Scientists have discovered lichens living inside Antarctic rocks that survive extreme cold, radiation, and desiccation - conditions remarkably similar to Mars. These cryptoendolithic organisms grow just micrometers per year, can live for thousands of years, and have remained metabolically active in Martian simulations, offering profound insights into life's limits and the potential for extraterrestrial biology.

The nonprofit sector has grown into a $3.7 trillion industry that may perpetuate the very problems it claims to solve by professionalizing poverty management and replacing systemic reform with temporary relief.

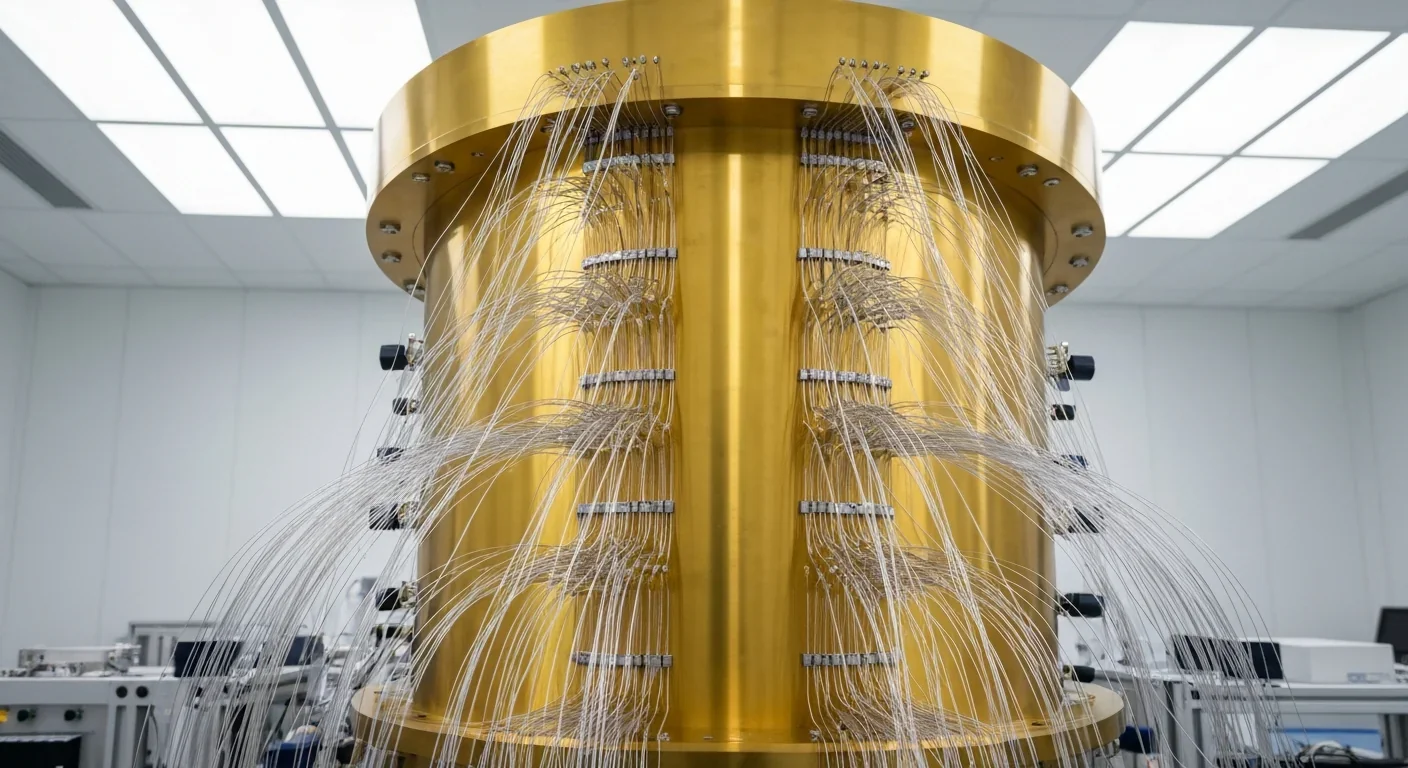

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.