Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Human-generated electromagnetic fields from cell towers, power lines, and wireless devices are disrupting the quantum-based magnetic navigation systems that billions of migratory birds rely on. This invisible pollution, operating at frequencies that scramble cryptochrome proteins in birds' eyes, may be causing mass disorientation along migration routes worldwide.

By 2050, scientists predict that electromagnetic interference could fundamentally alter migration patterns for billions of birds worldwide. What began as isolated incidents in the late 1990s has grown into a global phenomenon: migratory birds getting lost in their own sky.

The culprit? An invisible form of pollution that humans barely notice but birds cannot ignore. Every time you flip on a light, send a text message, or tune into the radio, you're contributing to an electromagnetic fog that's scrambling the internal compasses of millions of migratory birds. And unlike oil spills or plastic pollution, this threat is growing exponentially with every new cell tower and power line we build.

Inside the retina of every European robin, something extraordinary happens when blue light strikes a protein called cryptochrome 4. Electrons begin hopping between amino acid residues, creating pairs of particles whose quantum states remain eerily connected. These radical pairs don't just respond to Earth's magnetic field - they become a living compass operating at the edge of what quantum mechanics allows.

"We think these results are very important because they show for the first time that a molecule from the visual apparatus of a migratory bird is sensitive to magnetic fields."

- Henrik Mouritsen, University of Oldenburg

This isn't your grandfather's compass. Birds don't sense north and south poles the way a needle points. Instead, they perceive the inclination of magnetic field lines - the angle at which Earth's magnetic field intersects the planet's surface. Near the equator, field lines run parallel to the ground. At the poles, they plunge straight down. This gradient creates an invisible map that birds read as naturally as you read street signs.

The mechanism depends on something physicists thought was impossible in biological systems: quantum coherence. When cryptochrome 4 absorbs light, it maintains delicate quantum connections between electrons long enough to detect magnetic fields 50 times weaker than a refrigerator magnet. Evolution has somehow optimized this process over millions of years, pushing biological systems to perform feats that quantum computer engineers are still struggling to replicate in laboratories.

Before the 1990s, homing pigeon races were predictable affairs. Experienced racers could estimate arrival times down to the minute. Then came 1998 in Pennsylvania, and everything changed.

Soon after cell towers sprouted across the state, pigeon races ended in disaster. Up to 90% of birds disappeared, failing to return home. The pattern repeated across competitions. Champions that had flown the same routes for years suddenly couldn't find their way back. Some never returned at all.

At first, racing enthusiasts blamed weather, predators, or disease. But the timing was too consistent, the geographic pattern too clear. Every affected race occurred near newly installed cellular infrastructure. The invisible had become undeniable.

When researchers covered experimental huts with grounded aluminum sheeting, robins immediately regained their directional sense. Remove the shielding, and disorientation returned.

Around the same time, researchers in Germany began noticing something odd about their robin orientation experiments at the University of Oldenburg. Birds that had reliably oriented during migration season were suddenly showing random directional behavior. The problem persisted for years until someone thought to check the electromagnetic environment.

When researchers covered the experimental huts with grounded aluminum sheeting - blocking external electromagnetic noise but allowing Earth's static magnetic field through - the robins immediately regained their directional sense. Remove the shielding, and disorientation returned. The cause was clear: ambient electromagnetic noise from AM radio signals and electronic equipment was overwhelming the birds' magnetic compass.

Peter Hore at Oxford has spent years calculating what happens when radio-frequency fields interact with cryptochrome's radical pairs. The math reveals an uncomfortable truth: the same quantum sensitivity that makes avian magnetoreception possible also makes it devastatingly vulnerable to interference.

Radical pairs exist in quantum superposition - simultaneously in multiple states until something forces them to choose. Earth's magnetic field gently nudges this choice, providing directional information. But when radio-frequency fields matching the spin-state transition frequencies wash over these radical pairs, they scramble the signal beyond recognition.

Think of it like trying to hear a whisper in a windstorm. Earth's magnetic field is the whisper - constant, subtle, reliable. Human-generated electromagnetic fields are the windstorm - chaotic, overwhelming, impossible to filter out at the molecular level.

The problem isn't limited to narrow frequency bands. Research by Engels and colleagues in 2014 found that broadband radiofrequency interference - the kind produced by modern wireless infrastructure - can completely disable magnetic orientation in European robins. A mere 20 minutes of exposure to radiofrequency fields measuring just 5 microteslas (about one-hundred-thousandth the strength of Earth's magnetic field) caused total disorientation. When the interference stopped, navigation ability returned. Turn it back on, and the compass went blind again.

Ioannis Kominis, who studies quantum limits in biological systems, points out that cryptochrome operates near the Heisenberg uncertainty limit - the fundamental boundary of what quantum mechanics allows. There's no room for the system to become more robust against interference. Evolution has already pushed this biological technology to its absolute physical limits.

Not all birds face equal risk from electromagnetic pollution. Species that have evolved the most sophisticated magnetic navigation systems - the long-distance migrants that cross continents and oceans - appear most susceptible to interference.

European robins, studied extensively because they're common and migrate at night, show higher cryptochrome 4a expression during spring and fall migration seasons. This heightened sensitivity makes them exceptional navigators under natural conditions but also more vulnerable when electromagnetic interference increases.

Genomic analysis by Miriam Liedvogel revealed that cryptochrome 4 shows greater variation in migratory species compared to resident birds. Natural selection has fine-tuned this protein in birds that need it most - exactly the species now facing the greatest threat from electromagnetic pollution.

"Even subtle disruptions to the magnetic field can impact birds' ability to navigate. We would like to know how such extraordinarily weak radiofrequency fields could disrupt the function of an entire sensory system in a higher vertebrate."

- Peter Hore, University of Oxford

Homing pigeons, while not long-distance migrants, possess remarkable navigation abilities that made the 1998 Pennsylvania disasters particularly alarming. These birds represent thousands of generations of selective breeding for homing ability. If electromagnetic fields could disorient champion racing pigeons on familiar routes, what might they do to wild birds navigating unfamiliar territory for the first time?

Warblers, which undertake some of the most impressive migrations in the animal kingdom - crossing the Mediterranean Sea and Sahara Desert in single flights - rely heavily on magnetic orientation, particularly when crossing featureless terrain where visual landmarks provide no guidance. Any interference with their magnetic sense during these critical passages could prove fatal.

The risk extends beyond individual species to entire migratory systems. In North America alone, an estimated 7 billion birds undertake seasonal migrations. If even a small percentage experience orientation failures due to electromagnetic interference, we're talking about hundreds of millions of birds potentially affected.

Urban environments represent the most intense electromagnetic pollution zones. The University of Oldenburg campus, where researchers first documented electromagnetic interference with robin navigation, is hardly unique. Every city pulses with AM radio transmissions, FM broadcasts, TV signals, WiFi networks, cell tower emissions, and electrical grid radiation.

Power line corridors create electromagnetic highways that crisscross continents. High-voltage transmission lines generate fields strong enough to affect magnetoreception hundreds of meters away. Since many of these corridors parallel major geographic features like river valleys and mountain passes - the same features that concentrate migrating birds - interference hotspots overlap precisely with critical migration routes.

FCC limits on radiofrequency exposure were designed exclusively for human thermal effects - not protecting the quantum compass in a bird's eye. What's harmless to us may be catastrophic for species that depend on detecting fields millions of times weaker.

Coastal regions, where billions of birds concentrate during migration, have become increasingly saturated with electromagnetic infrastructure. Cell towers line shorelines to provide coverage for beach communities. Offshore wind farms, though crucial for renewable energy, add yet another source of electromagnetic fields along traditional migration corridors.

Even remote areas aren't immune. Radio and television broadcast towers often occupy high points with excellent sight lines - the same locations birds use as orientation landmarks. The irony is cruel: the places where birds most need reliable navigation are increasingly the places where electromagnetic interference is strongest.

Recent research suggests that 5G millimeter wave frequencies could present novel challenges. The wavelengths involved may resonate with the physical dimensions of magnetite crystals and other magnetic structures in bird tissues, potentially creating interference mechanisms different from traditional radiofrequency sources.

Over the past decade, the scientific case for electromagnetic interference with avian magnetoreception has moved from hypothesis to established fact. Multiple independent research teams have replicated the basic finding: radiofrequency fields disrupt bird orientation.

The 2021 Nature paper identifying cryptochrome 4 as the magnetic sensor represents a watershed moment. For the first time, scientists can study the exact molecular machinery responsible for magnetoreception. This opens doors to understanding not just whether electromagnetic fields cause interference, but precisely how they do it at the quantum level.

Researchers have begun mapping the specific frequencies that cause the most severe disruption. The challenge is daunting because the radiofrequency spectrum spans enormous ranges, and different bird species may show different vulnerabilities depending on subtle variations in their cryptochrome proteins.

Field studies are moving beyond laboratory demonstrations to assess real-world impacts. Researchers are tracking migration success rates near electromagnetic infrastructure, looking for correlations between field intensity and navigation errors. Early results suggest that even ambient urban electromagnetic noise - too weak to pose any health risk to humans - can significantly impair bird navigation.

One fascinating line of inquiry explores whether birds can adapt to electromagnetic pollution. Some researchers have proposed that birds might learn to rely more heavily on backup navigation systems - using the sun, stars, or visual landmarks when magnetic information becomes unreliable. But this redundancy comes at a cost. Integrating multiple navigation cues requires more complex neural processing and potentially increases energy expenditure during already demanding migrations.

"Physicists are excited by the idea that quantum coherence could not just occur in a living cell, but could also have been optimized by evolution."

- Peter Hore, on implications for quantum computing

The quantum physics community has taken notice. Understanding how cryptochrome maintains quantum coherence in the "warm, wet, and noisy" environment of a living cell could inform the development of more robust quantum computers and sensors. As Peter Hore notes, evolution may have already solved problems that still stump quantum engineers.

Current wildlife protection regulations barely acknowledge electromagnetic pollution as an environmental threat. In the United States, FCC limits on radiofrequency exposure were designed exclusively for human thermal effects - preventing tissue heating, not protecting the quantum compass in a bird's eye.

A comprehensive review of over 1,200 studies found adverse effects on orientation and migration at intensities far below levels considered safe for humans. The disconnect is stark: what's harmless to us may be catastrophic for species whose survival depends on detecting fields millions of times weaker.

Some researchers advocate for "electromagnetic quiet zones" along major migration corridors, similar to dark sky preserves that limit light pollution. The concept is straightforward but implementation is complex. How do you create radiofrequency quiet zones in a world that demands ubiquitous wireless coverage?

Technological solutions may offer alternatives. Modern communication systems can be engineered to minimize certain frequencies known to cause the worst interference. Directional antennas focus signals where they're needed rather than broadcasting omnidirectionally. Time-based approaches could reduce emissions during peak migration periods when birds are most vulnerable.

Shielding studies suggest another approach: if aluminum screening can protect robins in experimental huts, could similar principles protect birds along vulnerable migration routes? The engineering challenges are substantial, but not insurmountable.

The renewable energy transition adds urgency to these questions. Wind farms and solar installations require communication infrastructure for grid management. Done thoughtlessly, our attempt to solve one environmental crisis could exacerbate another. Done carefully, with wildlife impacts considered from the design phase, we might thread the needle.

Birds don't rely solely on magnetoreception to navigate. They integrate multiple cues: the sun's position, star patterns, visual landmarks, olfactory information, and magnetic fields. This redundancy provides resilience, allowing birds to compensate when any single system fails.

But electromagnetic interference doesn't just remove one cue from the navigation toolkit - it adds false information. Imagine your GPS not just turning off but instead showing you're somewhere you're not. That's potentially what birds experience when electromagnetic fields scramble their magnetic sense.

The cognitive load of filtering unreliable magnetic information while maintaining course using backup systems may explain why some studies show increased energy expenditure in birds navigating through high-electromagnetic environments. Already operating on razor-thin energy margins, migratory birds may arrive at stopover sites more depleted, reducing survival rates even if they successfully navigate.

Young birds face particular challenges. First-time migrants often fly routes they've never seen, guided by an inherited magnetic map. If electromagnetic interference corrupts this map during a bird's first migration, it may never successfully complete the journey.

Young birds face particular challenges. Unlike many navigation cues that can be learned through experience, magnetic orientation appears partly innate. First-time migrants often fly routes they've never seen, guided by an inherited magnetic map. If electromagnetic interference corrupts this map during a bird's first migration, it may never successfully complete the journey.

We've spent decades learning to see and address visible environmental damage: smog-choked skies, oil-slicked waters, plastic-strewn beaches. Electromagnetic pollution demands we grapple with threats we cannot perceive.

The invisibility creates psychological distance. It's hard to care about what you can't see, especially when that invisible thing powers technologies we've come to see as essential. Your smartphone isn't visibly harming anything. The cell tower near your house looks benign. But to a migrating bird, that infrastructure might represent an impenetrable wall of noise that obliterates the magnetic whispers it has evolved over millions of years to hear.

Scale adds complexity. We're not talking about a contaminated site that can be cleaned up or a chemical that can be banned. Electromagnetic fields are fundamental to how we've built modern civilization. Every wire carrying current, every antenna transmitting signals, every electronic device switching transistors creates electromagnetic fields. The question isn't whether to eliminate electromagnetic emissions - that's impossible - but how to manage them in ways that allow both human technology and natural navigation systems to coexist.

Some scientists worry we're running a massive, uncontrolled experiment on migratory systems that took millions of years to evolve. We're flooding the environment with electromagnetic signals and hoping birds can adapt fast enough. History suggests caution. DDT seemed safe until we noticed eggshells thinning. CFCs seemed harmless until we found a hole in the ozone layer. We're not great at predicting the cascade effects of invisible pollutants.

Hope exists, but it requires acknowledging the problem and acting deliberately rather than waiting for decline to become impossible to ignore.

First, we need better monitoring. Current data on electromagnetic exposure levels along migration routes is patchy at best. Comprehensive mapping would identify the worst hotspots and guide mitigation efforts where they're needed most.

Second, we need regulatory frameworks that account for non-thermal biological effects. This doesn't necessarily mean draconian restrictions on technology, but it does mean thoughtful engineering and placement of electromagnetic infrastructure. Wildlife-conscious design principles should be as standard as energy efficiency requirements.

Third, we need technological innovation focused on reducing ecological electromagnetic footprints. Engineers who designed our current systems had no idea cryptochrome proteins existed, let alone that radiofrequency interference could scramble quantum radical pairs. Armed with this knowledge, we can do better.

Fourth, we need international cooperation. Birds don't respect borders, and neither do electromagnetic fields. A bird encountering disorienting interference anywhere along its migration route faces increased mortality risk. Protection must span continents to be effective.

The renewable energy transition offers an opportunity to get this right from the start. As we build new infrastructure to replace fossil fuels, we can incorporate wildlife protection into the design rather than retrofitting it later. Solar installations and wind farms will require communication systems - can we build those systems to minimize their electromagnetic impact on local wildlife?

At least 7 billion birds migrate across North America each year. Globally, the number reaches into the hundreds of billions. These migrations connect ecosystems across continents, moving nutrients, dispersing seeds, controlling insect populations, and maintaining ecological relationships that predate human civilization.

What happens if electromagnetic interference causes even a small increase in migration mortality? A 5% decline might sound manageable until you realize that's hundreds of millions of birds failing to complete journeys they've made for millennia. Population collapse can happen faster than we expect, particularly for species already stressed by habitat loss, climate change, and other human impacts.

We're in a strange moment where our understanding of the problem has advanced faster than our response. We know electromagnetic fields interfere with avian magnetoreception. We know the interference can cause disorientation and navigation failure. We know which frequencies are most problematic. We even know some potential solutions.

What we don't know is whether we'll act on this knowledge before migration systems that evolved over millions of years unravel in a few decades of electromagnetic proliferation.

The birds flying over your head tonight, navigating by quantum compasses sensitive to fields you can't feel, represent a test of whether humanity can manage its technological power with enough wisdom to preserve systems we didn't create and barely understand. Their fate may reveal more about us than about them.

In the quantum mechanics underlying bird navigation, scientists have found that nature operates at the edge of what physics allows - maximally sensitive, impossibly precise, fine-tuned by eons of selection. We've built a world of electromagnetic signals in just a few generations. The question now is whether we're clever enough to let both systems coexist, or whether the invisible pollution we've created will prove as destructive as any oil spill, just harder to see and harder to clean up.

The answer may determine whether billions of birds continue their ancient journeys, or whether future generations will inherit skies a little emptier, a little quieter, missing something precious they never knew was there.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

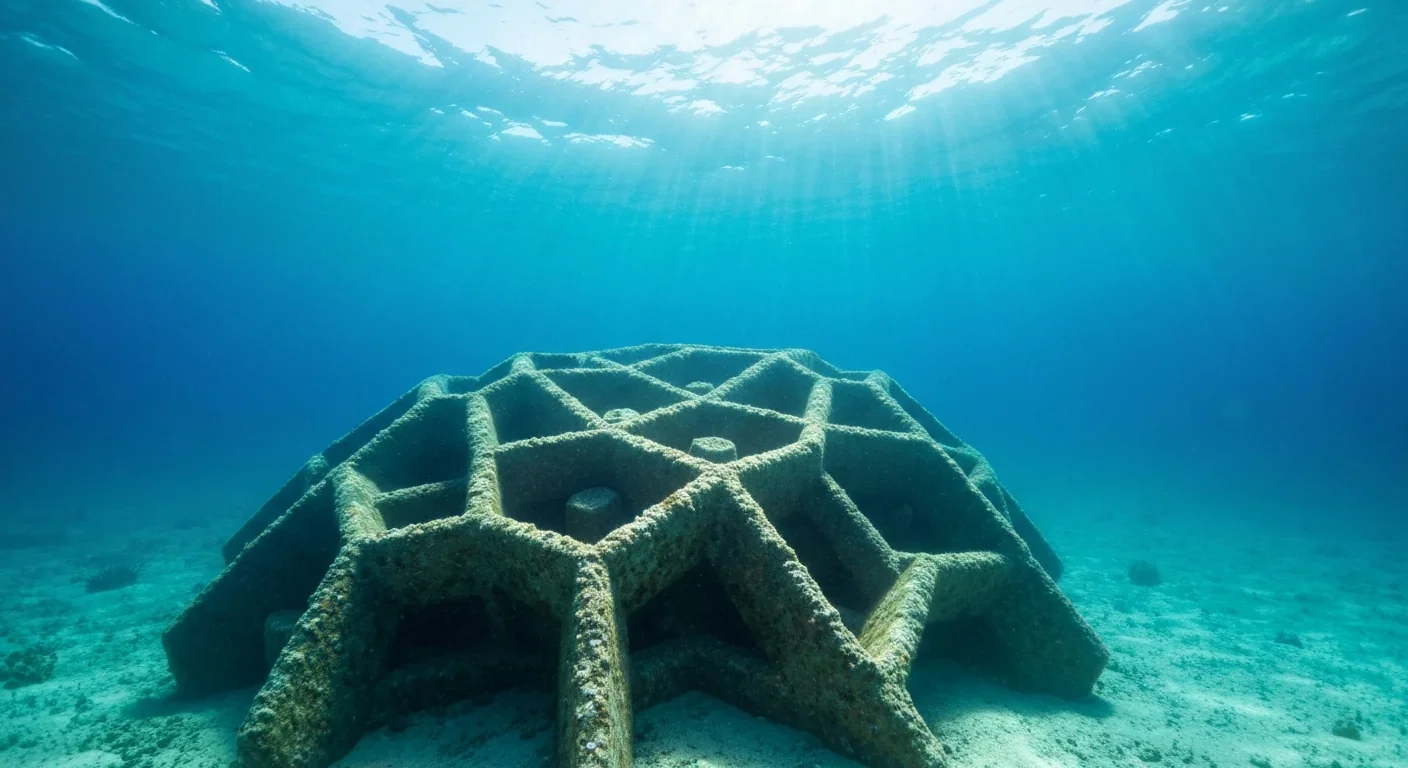

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

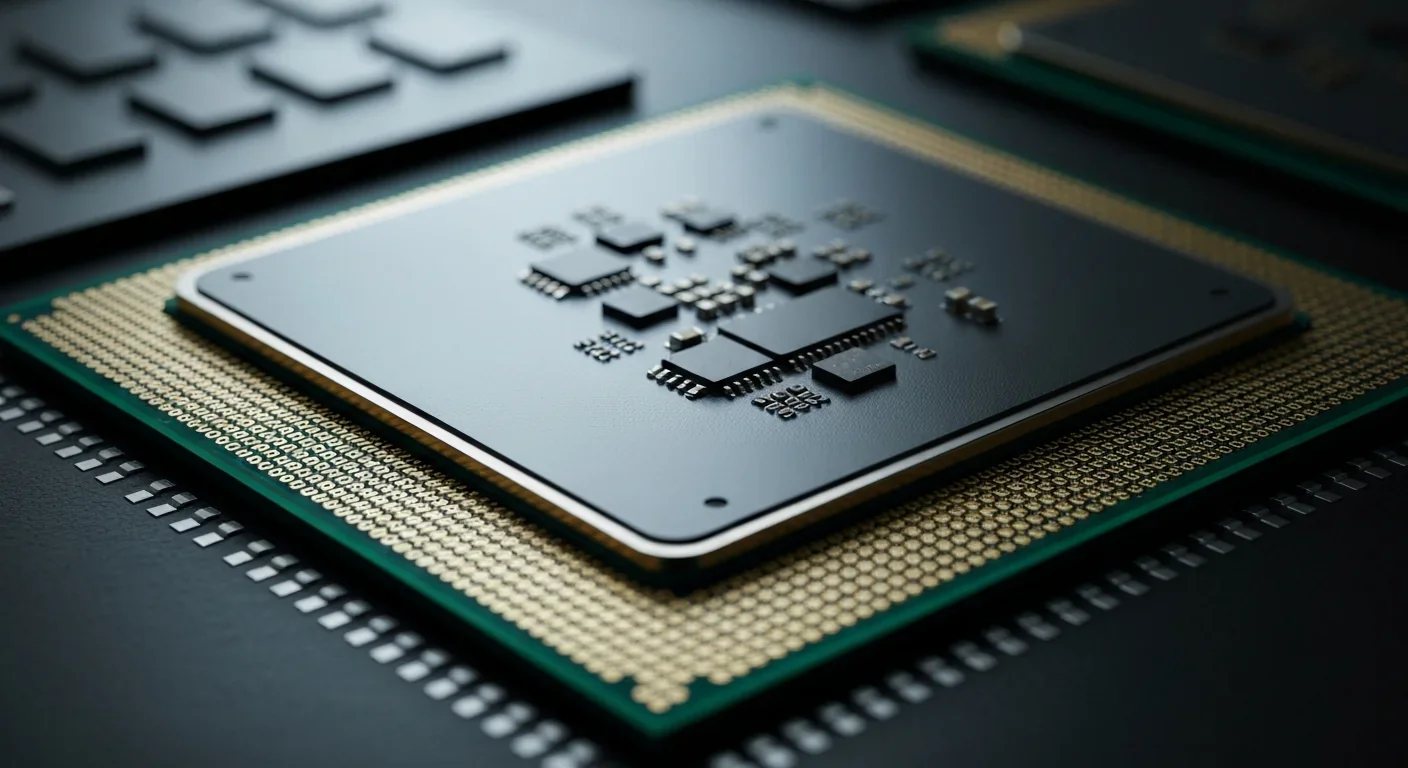

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.