Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Scientific research reveals that grief isn't uniquely human - elephants, orcas, primates, birds, and pets display measurable mourning behaviors including vigils, physiological stress responses, and cultural rituals passed between generations.

In 2018, a female orca named Tahlequah captured global attention when she carried her dead calf for 17 days across 1,000 miles of Pacific waters. Marine biologists watched in astonishment as this mother refused to let go, balancing her baby's body on her head, diving to retrieve it when it slipped away. It wasn't illness or confusion driving this behavior - it was grief. And she's far from alone in the animal kingdom.

For decades, we've wondered whether animals truly mourn their dead or simply react to absence with confusion. The answer emerging from research labs and field stations worldwide is reshaping how we understand consciousness itself: grief isn't uniquely human. It's woven into the social fabric of species from elephants to crows, from dolphins to the dog sleeping at your feet.

Scientists face a tricky challenge when studying animal emotions. You can't exactly ask an elephant how it feels. So researchers look for objective markers: behavior changes, physiological stress responses, and patterns that mirror human grief.

Dr. Joyce Poole, who's studied elephant behavior for over 40 years, has documented more than 30 distinct mourning behaviors. Elephants don't just walk away from their dead. They stand vigil for days, gently touching the body with their trunks - those incredibly sensitive organs capable of both tremendous strength and delicate caresses. They cover corpses with branches and dirt, sometimes attempting to lift the fallen as if trying to help them stand.

What's remarkable is the persistence. Field researcher Cynthia Moss recorded instances where elephant families traveled significantly out of their way to visit sites where relatives had died - years after the death occurred. Using their trunks, they gently examine the bones, particularly skulls and tusks, in what appears to be recognition.

This isn't projection or storytelling. Hormonal studies have detected elevated cortisol levels in elephants following a herd member's death, providing physiological evidence of distress. Their bodies are responding to loss the same way ours do.

Tahlequah's story resonated worldwide because it felt achingly familiar. But her behavior fits a broader pattern documented in cetaceans. Dolphins and whales have been observed supporting dead calves at the water's surface, unable or unwilling to accept death.

A second orca in Washington waters was spotted months later carrying a dead newborn, repeating the heartbreaking ritual. These aren't isolated incidents - marine biologists have documented similar behaviors across different whale and dolphin species worldwide.

Frans de Waal, a primatologist who's spent his career studying animal cognition, notes that the species experiencing the most profound grief tend to share something crucial: robust social structures. When your survival depends on complex relationships, when you remember individuals and their roles in your community, loss carries weight.

The great apes - our closest relatives - show mourning behaviors that feel uncomfortably familiar. Chimpanzees and gorillas carry deceased infants for days or weeks, exhibiting depressive-like behaviors and unique vocalizations.

Jane Goodall's early field notes from Gombe described what she called a chimpanzee funeral: the group fell silent, groomed the deceased, and maintained a vigil. Some communities show specific cultural practices - certain groups consistently remove leaves from corpses, others use distinct vocalizations found nowhere else.

That word "cultural" is deliberate. Research suggests these aren't purely instinctive responses but learned behaviors passed between generations. Younger chimps adopt mourning rituals by watching elders, meaning different communities have different traditions around death.

Corvids - crows, ravens, and jays - perform what scientists have termed "funerals," though that label makes some researchers uncomfortable. When a crow dies, others gather around the body, vocalizing distinct calls and sometimes placing objects nearby.

A study published in Animal Behaviour found that crows avoided areas where they'd seen dead crows for at least three months. Western scrub jays call to summon others to a deceased group member, creating gatherings that serve unclear purposes - warning about danger? Acknowledging loss? We're still figuring it out.

These birds possess remarkable cognitive abilities, including the capacity to remember individual faces and plan for the future. It makes sense that species capable of such complex thought might also grapple with the permanence of death.

If you've ever lost a pet and watched your surviving animals behave strangely afterward, you weren't imagining things. A 2022 study in Scientific Reports surveyed over 400 Italian pet owners who'd lost a dog or cat. A striking 86% reported observable changes in their surviving animals.

These changes weren't subtle. Dogs and cats showed decreased appetite, lethargy, changed sleep patterns, and increased vocalizations. The behaviors averaged two months in duration - remarkably similar to acute grief phases in humans.

Functional MRI studies of dog brains show activation in regions homologous to human areas involved in processing social bonds. When dogs form attachments, their brains light up in ways that suggest genuine emotional connection. It follows that breaking those bonds would register as loss.

Horses, too, show grief-like distress responses after losing a companion. They may refuse food, exhibit anxious behaviors, and search repeatedly for the missing individual. Pet owners describing these changes aren't projecting human emotions - they're observing real behavioral shifts with measurable physiological correlates.

What's happening in these animals' brains? A 2020 study in Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews found elevated cortisol - a stress hormone - in many mammalian species following separation from bonded companions.

This isn't about anthropomorphism. It's about recognizing that similar brain structures often serve similar functions across species. Mammals share neural architecture for social bonding, emotional regulation, and stress response. A dog's amygdala, hippocampus, and anterior cingulate cortex aren't identical to ours, but they're remarkably similar.

When we form attachments, specific neural pathways strengthen. Breaking those connections triggers a cascade of neurochemical changes - decreased dopamine and serotonin, elevated cortisol, altered sleep-wake cycles. There's no reason to assume these mechanisms operate exclusively in humans.

From an evolutionary perspective, mourning seems counterproductive. Time spent with the dead is time not spent foraging, mating, or avoiding predators. So why does it persist across so many species?

One hypothesis suggests that mourning behaviors strengthen group cohesion. By gathering around the deceased, animals reinforce social bonds with the living, clarifying who remains in the group and what roles need filling.

Grief responses might also serve disease-prevention functions. Investigating a corpse carefully before abandoning it allows animals to assess whether illness, predators, or environmental hazards caused the death - information crucial for survival.

In elephants, mourning may help transfer ecological knowledge from matriarchs to younger members. The death of a matriarch represents the loss of decades of experience about water sources, migration routes, and seasonal patterns. The grieving process might help the herd process this transition and consolidate the knowledge she passed along.

Perhaps the most fascinating discovery is that mourning rituals appear culturally learned in some species. Elephant populations in different regions exhibit region-specific "grief calls" - distinctive vocalizations used exclusively in death contexts.

Certain chimpanzee communities practice leaf removal from corpses and specific vocalizations that vary between groups. These behaviors aren't instinctual; they're passed down through observation and imitation.

Different orca pods maintain unique traditions around many behaviors, from hunting techniques to communication patterns. It wouldn't surprise researchers if mourning practices also vary between pods, representing cultural knowledge accumulated over generations.

Walking the line between anthropomorphism (over-attributing human qualities to animals) and anthropodenial (dismissing legitimate animal emotions) challenges researchers constantly.

Scientists establish rigorous criteria before calling a behavior "grief." They look for multiple indicators: changes in normal behavior patterns, physiological stress markers, duration of response, and whether the behavior serves clear survival functions or appears emotionally driven.

The goal isn't to prove animals feel exactly what humans feel. It's to understand what they do feel on their own terms. An elephant's grief might differ from human grief in important ways while still being genuine emotional distress at losing a companion.

If your dog or cat seems depressed after losing a companion animal, supporting them through grief involves several strategies.

Maintain routine as much as possible - familiar schedules provide comfort during upheaval. Increase positive interactions without overwhelming the animal. Some pets benefit from extra attention; others need space to process.

Watch for signs that grief has shifted into clinical depression: refusing food for extended periods, complete withdrawal from activities, or behavior changes lasting beyond a few months. Your veterinarian can assess whether intervention is needed.

Interestingly, allowing surviving pets to see the deceased animal's body might help. While research is limited, some behaviorists suggest this provides closure, helping animals understand the companion won't return rather than endlessly searching.

Understanding animal grief transforms wildlife management and conservation strategies. Poaching doesn't just reduce elephant numbers - it traumatizes surviving herd members, potentially affecting reproduction rates and social stability for years.

Some reserves now implement "trauma counseling" programs for elephants who've witnessed killings, recognizing that psychological welfare affects conservation outcomes. Similarly, wildlife relocations consider social bonds more carefully, avoiding separations that could trigger grief responses affecting survival.

The story of the "world's loneliest elephant" - who died after 13 years of isolation in an Indian zoo - illustrates the consequences of ignoring animals' social and emotional needs. Elephants aren't just biologically social; they're emotionally dependent on companionship.

Conservation ethics increasingly incorporate questions about animal suffering beyond physical pain. If removing a key group member causes genuine grief in survivors, that suffering should factor into management decisions.

Recognizing animal grief carries ethical weight. It complicates industries and practices that separate bonded animals or cause deaths that trigger mourning in survivors.

It challenges how we think about consciousness and emotion. If grief - one of our most distinctly "human" experiences - appears across diverse species with varying cognitive abilities, what does that say about the inner lives of the animals around us?

The evidence suggests we share the planet with creatures capable of genuine emotional depth. They form attachments, experience loss, and sometimes struggle to move forward after that loss - just like we do.

Research into animal mourning continues expanding. New technologies - from non-invasive hormone monitoring to advanced brain imaging - let scientists study grief responses with unprecedented precision.

Key questions remain: How do environmental factors influence mourning duration in different species? Do animals experience anything analogous to complicated grief or PTSD after traumatic losses? Can understanding animal grief inform human psychology and grief therapy?

Studies are also exploring whether emotional support works for grieving animals the way it does for humans. Can interventions reduce suffering or help animals adapt more quickly?

The science is clear: grief isn't uniquely human. It's ancient, widespread, and deeply rooted in the biology of social connection. From elephants returning to the bones of relatives to your dog acting strangely after losing a companion, mourning behaviors reflect genuine emotional responses to loss.

This doesn't mean all animals grieve identically or that every species experiences death the same way. But it does mean we're not alone in struggling with mortality and absence. The capacity to mourn - to recognize that someone who mattered is gone - appears to be part of what social bonds cost across the animal kingdom.

Tahlequah eventually let her calf go after those 17 days. Scientists watching her wondered whether the tour of grief served a purpose - processing loss, saying goodbye, or simply refusing to accept the unacceptable for as long as possible. We may never know exactly what she felt.

But we know this: she wasn't confused. She wasn't sick. She was a mother who'd lost her baby, doing what countless grieving animals do - holding on until she was ready to let go.

That recognition changes how we see the animals in our homes, in our zoos, and in the wild spaces we're still fortunate enough to share with them. They're not so different from us, not when it comes to love, connection, and the pain of losing those we hold dear.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

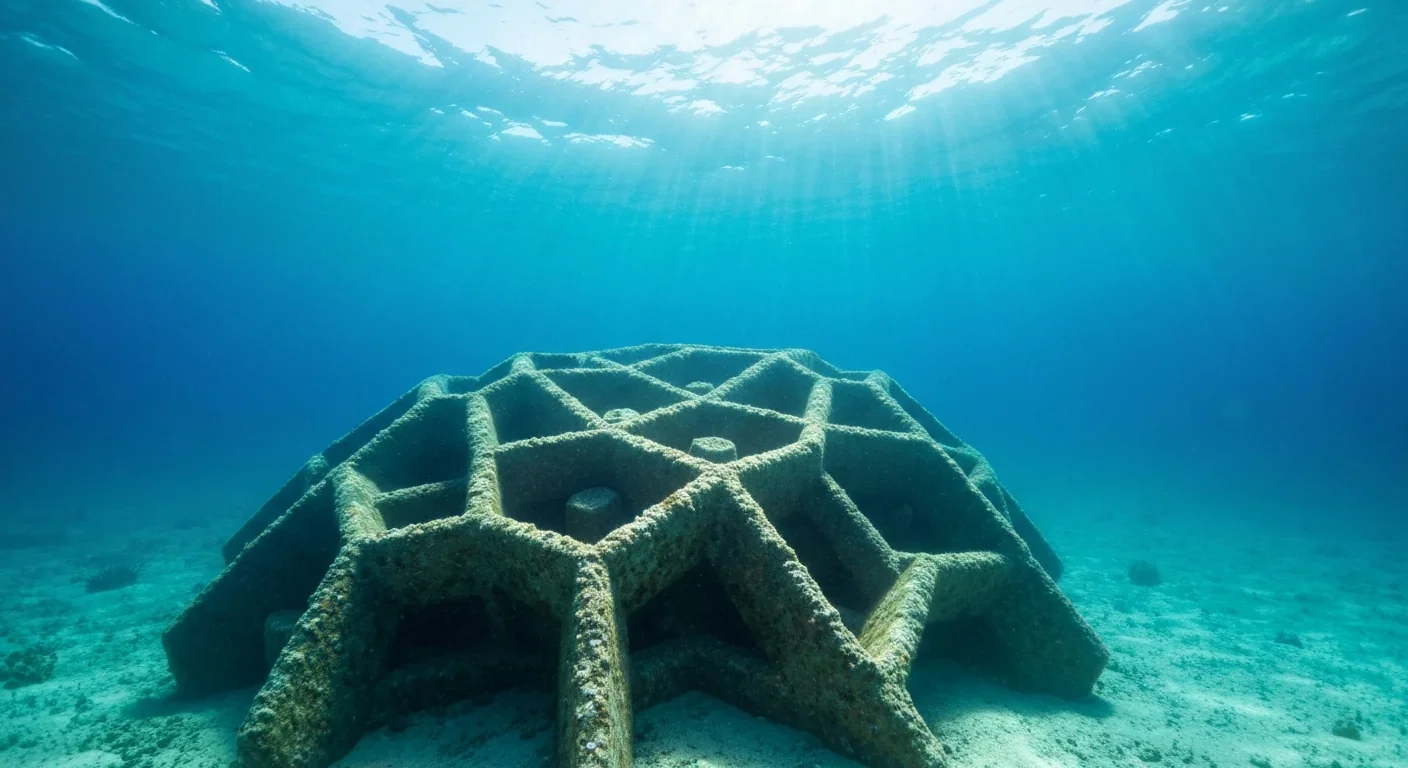

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

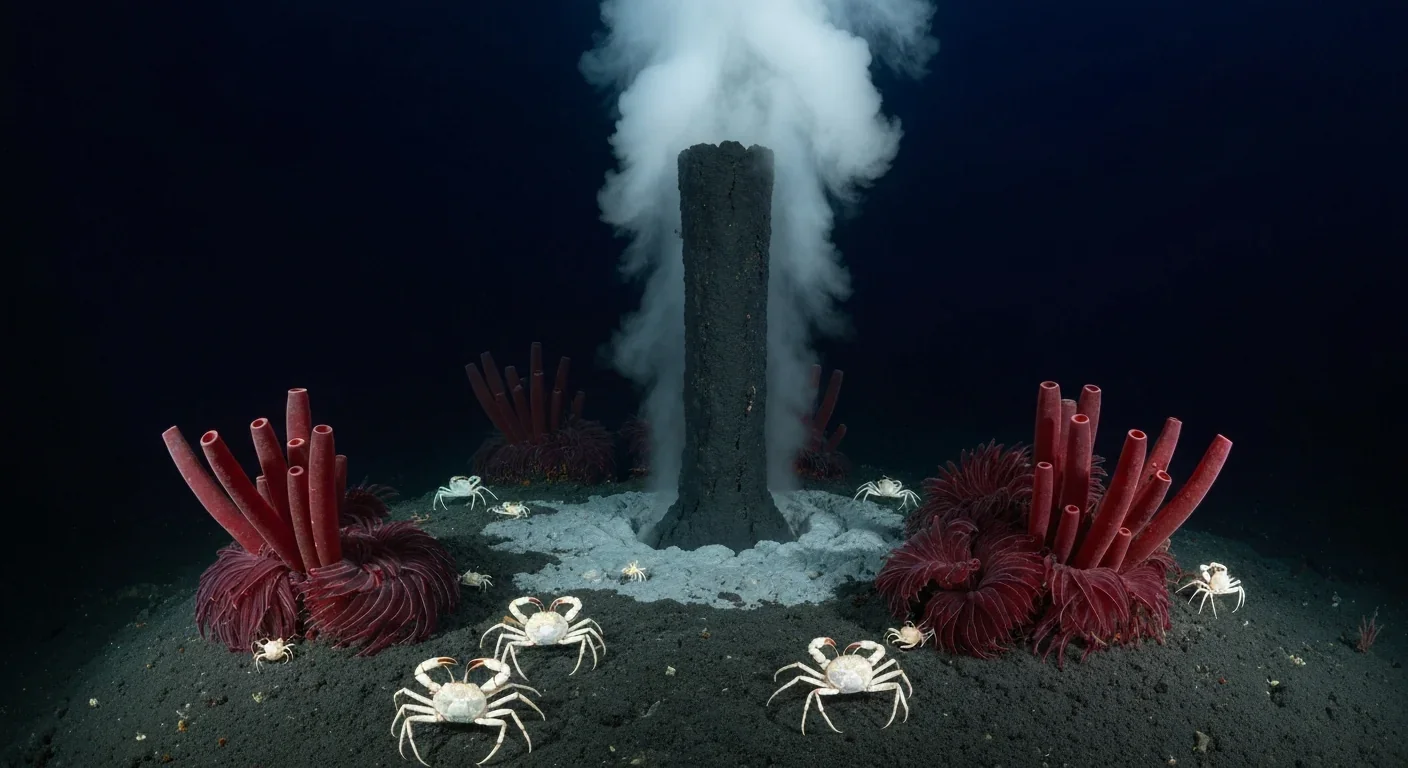

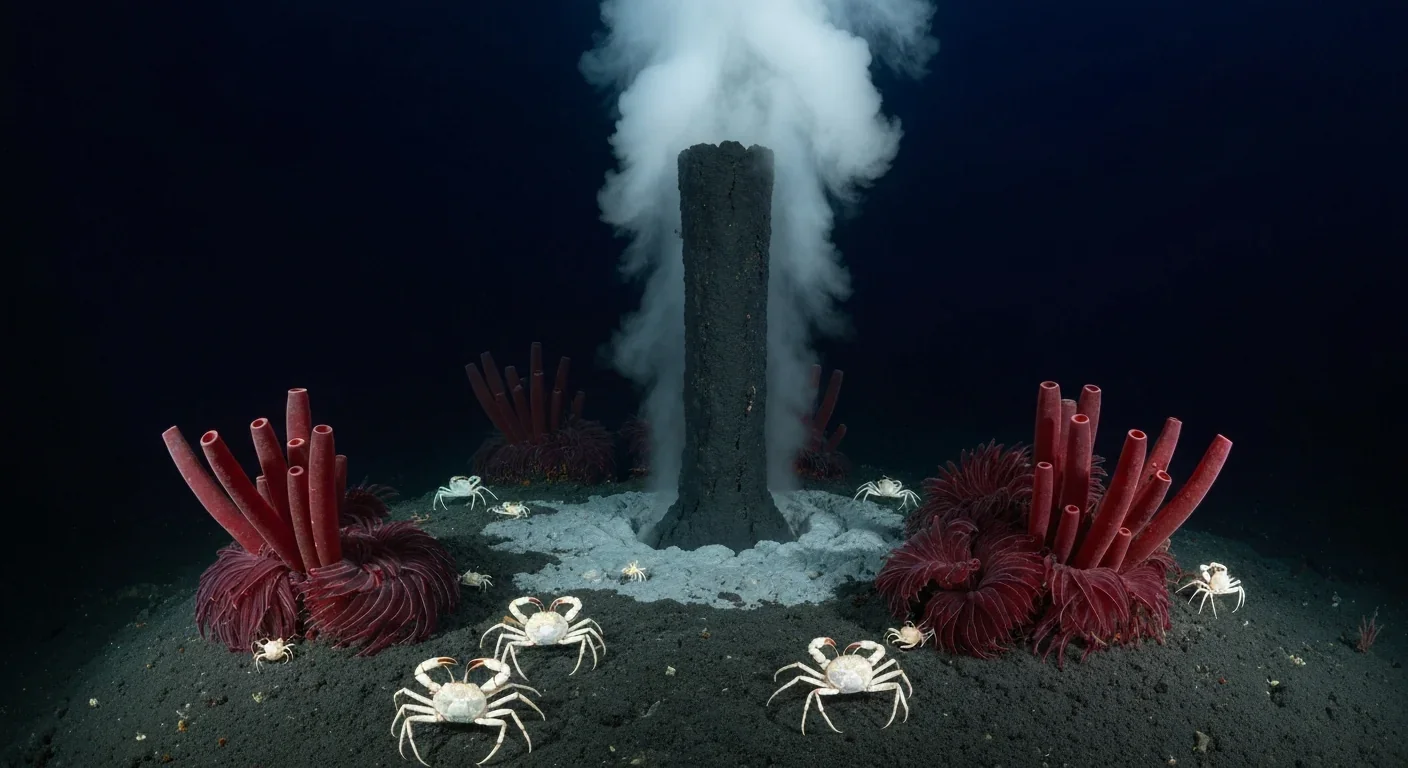

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

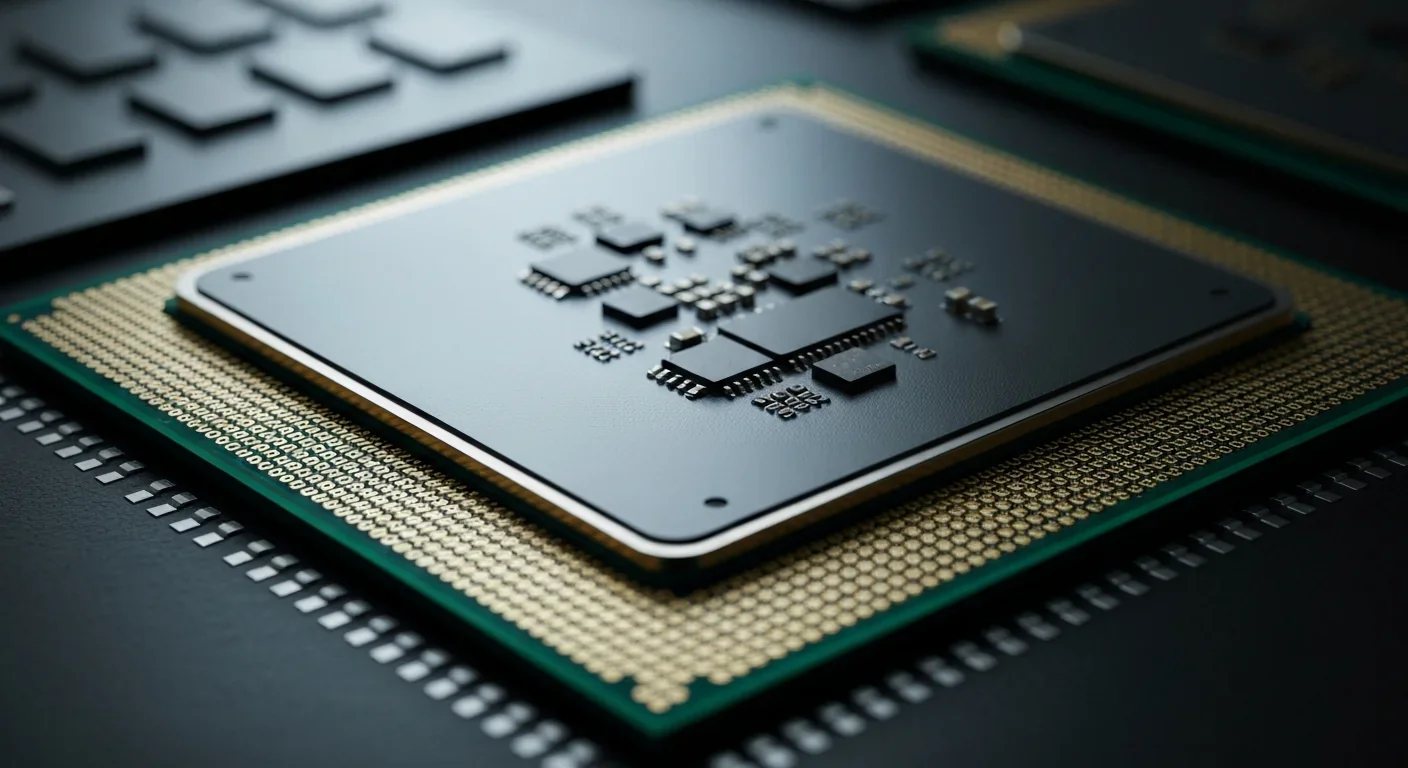

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.