Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Scientific evidence reveals that elephants, orcas, primates, crows, and even insects exhibit measurable grief behaviors when companions die. These mourning rituals evolved as the evolutionary price of social bonds, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of animal consciousness and the ethical obligations we owe to grieving species.

In North Bengal, India, researchers captured footage that challenged everything we thought we knew about animal emotion. An elephant herd gathered around a drainage ditch, carefully positioning the body of a dead calf before methodically covering it with mud. For nearly an hour, the adults trumpeted - a haunting, sustained vocalization that echoed across the landscape. The elephants had just conducted what can only be described as a burial ritual.

This wasn't isolated behavior. Across five documented cases, Asian elephants demonstrated intentional burial practices that mirror human mourning ceremonies. But elephants aren't alone in their grief. From orcas carrying deceased calves for weeks to crows gathering in "funerals" around their dead, the animal kingdom is revealing an emotional depth that forces us to reconsider what it means to mourn.

The implications stretch far beyond scientific curiosity. Understanding animal grief reshapes conservation priorities, challenges our ethical frameworks, and illuminates the evolutionary roots of empathy itself. What we're discovering suggests that mourning isn't uniquely human - it's a fundamental response to loss shared across species, each expressing sorrow in ways shaped by millions of years of evolution.

Recent research has moved beyond anecdotal observations to document measurable grief responses in animals. Akashdeep Roy's 2024 study from the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research provided unprecedented evidence: elephants don't just recognize death; they actively respond to it with behaviors that meet scientific criteria for mourning.

The burial sites Roy documented showed strategic placement. Elephants positioned calves into muddy trenches and deliberately covered them with earth, leaving only legs protruding. Footprints around the carcasses confirmed adult elephants had spent considerable time at these locations. The sustained vocalizations - nearly 60 minutes of trumpeting - suggested emotional distress rather than mere curiosity.

Professor Leanne Proops, who studies elephant cognition, notes that elephants also interact with the bones of deceased herd members. They touch and sniff skulls and tusks, behaviors that suggest recognition and possibly memory of the deceased individual. These aren't random encounters; the elephants display what researchers call "attentiveness" - focused, deliberate engagement with remains.

The scientific community now recognizes that grief behaviors manifest across multiple species in observable, measurable ways. Physiological markers include changes in vocalization patterns, altered social behaviors, reduced feeding, and physical proximity to deceased companions. What was once dismissed as anthropomorphism - projecting human emotions onto animals - is now documented as genuine emotional processing.

Marine mammals display some of the most dramatic grief responses documented. Tahlequah, a southern resident orca, carried her dead calf for 17 days in 2018, pushing the 400-pound body through more than 1,000 miles of ocean. The behavior, which researchers termed a "tour of grief," required enormous physical effort and prevented normal feeding patterns.

Years later, Tahlequah began carrying another deceased calf, demonstrating that this wasn't a singular anomaly. Multiple orca mothers have exhibited similar behaviors, sometimes carrying dead young for over 11 days. The pattern is consistent: mothers refuse to abandon their calves, supporting them at the surface to prevent sinking, and defending the bodies from scavengers.

Primates show equally compelling evidence of grief. Jane Goodall, whose groundbreaking observations of chimpanzees transformed our understanding of animal emotion, documented mothers carrying dead infants for days or weeks. The mothers groomed the bodies, attempted to nurse them, and showed visible distress when separated from remains.

A 2019 study published in ScienceDaily revealed that primate responses to death differ from human bereavement in significant ways. While humans typically remove bodies quickly, many primate species maintain physical contact with deceased group members for extended periods. Mothers show reluctance to abandon infants, but the behavior appears driven by confusion about the permanence of death rather than denial.

Recent research from University College London found that primate mothers display bereavement responses distinct from human patterns. They continue maternal behaviors like grooming and cradling, sometimes for weeks after death. This suggests that understanding death as a permanent state may develop differently across species.

Even domesticated animals demonstrate grief. A groundbreaking 2024 study found that cats grieve the death of companion pets, including dogs. Cats showed reduced appetite, increased sleep, and decreased play activity after losing a household companion. The findings challenge assumptions that cats are solitary and emotionally detached.

Cattle also display mourning behaviors that most people never witness. In viral footage, a mother cow attempted to protect her stillborn calf from farm workers, positioning her body between them and the deceased young. The determination and distress were unmistakable, prompting discussions about animal welfare in agricultural settings.

Crows have developed what biologists describe as funeral assemblies - gatherings of dozens of birds around a deceased member of their species. These aren't random congregations. Research shows that crows learn to recognize dangerous locations through these gatherings, essentially creating cultural memories of where deaths occurred.

The behavior serves multiple functions. Bay Nature reports that crows produce distinct alarm calls when encountering dead crows, summoning nearby flock members. The assembled birds observe the scene, sometimes for hours, and demonstrate measurable behavioral changes afterward - avoiding the location and showing heightened vigilance when they must pass through the area.

But is this mourning or threat assessment? Scientists debate whether crow funerals represent emotional responses or purely functional information gathering. The answer may be both. Evolution rarely creates single-purpose behaviors; crow assemblies likely combine threat assessment with social bonding and possibly emotional processing.

Discovery Wild Science examined whether crows hold funerals or just really weird meetings. The research suggests crows remember individual dead birds and the circumstances of death, teaching younger flock members to avoid dangerous situations. This cultural transmission of information resembles how human societies use funerals to reinforce social bonds and share warnings.

The gatherings demonstrate corvid intelligence extending beyond immediate survival. Crows invest time and energy in behaviors that provide no immediate benefit, suggesting either sophisticated risk calculation or genuine emotional response - possibly both operating simultaneously.

The most surprising revelations come from studying creatures we rarely associate with emotion. Ants, bees, and other social insects engage in necrophoresis - the removal and burial of dead colony members. While initially explained as purely hygienic behavior, recent research reveals more complex patterns.

Honeybees don't just remove dead bees; they perform specific inspection behaviors, spending time with deceased hive members before removal. The process resembles quality control, but the time invested suggests something beyond immediate contamination concerns.

Atlas Obscura documented the surprisingly long history of humans conducting funerals for insects, particularly bees. These human rituals reflected observations that insects themselves seemed to treat death as significant. While we can't know if insects experience grief as mammals do, their behavioral responses to death show complexity that challenges simplistic explanations.

The evolutionary emergence of death-related behaviors in insects raises profound questions. If creatures with nervous systems vastly different from mammals respond to death with ritualized behaviors, what does this suggest about the fundamental nature of mortality recognition across life forms?

Why would evolution favor mourning behaviors that seem counterproductive? Carrying a dead calf requires enormous energy. Remaining near a carcass invites disease and predators. Spending hours gathered around a dead flock member diverts attention from feeding and reproduction.

The answer lies in the social complexity that defines many species. Animals that live in tight-knit groups with long-term relationships benefit from strong attachment bonds. These bonds motivate cooperation, coalition formation, and mutual protection. But powerful attachments come with a cost: they don't switch off instantly when a companion dies.

Psychology Today explored how animals conceptualize death, finding striking similarities to human cognition. Many species recognize death as a changed state, even if they don't fully grasp its permanence. The cognitive machinery that enables recognizing death likely evolved because understanding this state provided survival advantages - knowing when companions can no longer contribute to group defense or food sharing.

Susana Monsó, in her book examined by The New Yorker, argues that animals possess varying levels of death awareness. Some species show no recognition of death as different from sleep or temporary absence. Others demonstrate understanding that death represents permanent cessation of function. The spectrum of death awareness corresponds roughly to social complexity and cognitive capacity.

Mourning behaviors may persist because the emotional bonds that motivate them provide benefits that outweigh occasional costs. An orca mother who carries her calf for weeks loses feeding opportunities, but the intense mother-infant bond that creates this response also drives the extraordinary care that gives living calves high survival rates.

The evolutionary perspective suggests grief isn't a flaw in emotional programming - it's the price of love. Species that form powerful attachments inevitably experience powerful grief when those bonds break.

The existence of animal mourning forces confrontation with uncomfortable questions about consciousness and subjective experience. If an elephant deliberately buries its dead and calls out for an hour, is it experiencing something we would recognize as sorrow?

Emory University surveyed experts on animal emotions and consciousness, finding growing consensus that many species possess emotional experiences with subjective qualities. The question shifts from "Do animals have emotions?" to "How do animal emotions compare to human experiences?"

A-Z Animals compiled extensive documentation of animals that hold grieving rituals, demonstrating that mourning appears across taxonomic groups. The parallel evolution of grief-like behaviors suggests either common ancestry or convergent evolution driven by similar social pressures.

Wikipedia's overview of emotion in animals catalogs centuries of observations and modern research. Darwin himself argued that emotional continuity existed between humans and other animals, an idea that fell out of favor during behaviorism's dominance but has regained scientific credibility.

The ritual behaviors animals display challenge the assumption that only humans create meaningful ceremonies. When crows gather around their dead, elephants bury calves, and orcas refuse to abandon deceased young, we observe behaviors that meet any reasonable definition of ritual - repeated, formalized responses to significant life events.

Recognizing animal grief transforms conservation priorities. If animals experience emotional suffering from loss, then population management, captivity practices, and habitat protection must account for social bonds and emotional welfare.

The southern resident orca population, which includes Tahlequah, faces extinction. With only 73 individuals remaining, every death represents catastrophic loss - not just genetically but emotionally. When an orca carries a dead calf, we witness individual suffering compounding population-level crisis.

Zoo and aquarium management increasingly considers emotional welfare. Separating bonded animals causes demonstrable distress. Animal-Ko examined how captive animals grieve companions, finding that elephants, primates, and cetaceans show depression-like symptoms after separations or deaths.

Agricultural practices face ethical scrutiny when we acknowledge that cattle, pigs, and chickens form attachments and experience grief. The mother cow defending her stillborn calf wasn't exhibiting mechanical behavior - she was experiencing loss.

Helping cats cope with grief when household companions die involves recognizing behavioral changes and providing support. Veterinarians now recommend gradual introductions when replacing deceased pets and maintaining routines to provide stability.

Studying animal grief illuminates the foundations of empathy. If diverse species independently evolved responses to others' deaths, empathy may represent a fundamental feature of social cognition rather than a uniquely human achievement.

Reddit communities share heartbreaking and beautiful observations of animal grief, creating collective awareness of emotional continuity across species. These narratives shift public consciousness, making abstract research findings tangible through specific stories.

BBC Future investigated why some animals appear to mourn, concluding that the behaviors serve both practical and emotional functions. The same way human funerals simultaneously dispose of bodies, reinforce social bonds, and process grief, animal mourning likely serves multiple adaptive purposes.

Exploring Animals documented that some species react to death in surprisingly strange ways that don't fit neat categories of mourning. Dolphins sometimes engage in what appears to be play with deceased companions. Lions occasionally consume dead pride members. These behaviors remind us that animal responses to death evolved to solve species-specific challenges, not to mirror human expectations.

The diversity of mourning behaviors reflects the diversity of social systems. Solitary species show minimal death responses. Highly social species with stable, long-term groups show the most elaborate mourning. This correlation supports the theory that grief evolved as a byproduct of the attachment systems that enable complex cooperation.

Despite remarkable progress, fundamental questions persist. How do animals conceptualize death? Do they understand it as permanent? Can they anticipate their own mortality?

Ritual behavior in animals encompasses more than mourning, including courtship displays, play, and territorial marking. Understanding which behaviors qualify as truly ritualistic requires careful definition. If ritual implies symbolic meaning, can we attribute symbolic thinking to non-linguistic species?

The study of animal grief sits at the intersection of ethology, neuroscience, philosophy, and conservation biology. Future research will likely employ brain imaging to identify neural correlates of grief across species, comparative studies to trace mourning behaviors' evolutionary origins, and longitudinal observations to understand how animals process grief over time.

Technology enables unprecedented documentation. Camera traps, drones, and tracking devices capture private moments of animal life previously invisible to researchers. As elephant cognition studies advance, we may discover that current understanding barely scratches the surface of their emotional complexity.

The gharial mother attempting to save her dead calf from hyenas demonstrated protective instincts that persisted beyond rational utility. These observations accumulate into an undeniable conclusion: the emotional lives of animals contain depths we're only beginning to fathom.

Recognizing animal grief doesn't diminish human experience; it contextualizes our emotions within a broader evolutionary narrative. We aren't separate from nature - we're one expression of consciousness among many.

The implications extend to environmental policy, ethical consumption, entertainment industries that use animals, and research practices involving animal subjects. If animals grieve, causing them to lose companions constitutes genuine harm requiring ethical justification.

Perhaps most significantly, understanding animal mourning expands our circle of moral concern. When we observe an orca carrying her dead calf for weeks or an elephant trumpeting over a buried infant, we recognize kinship. The line separating human from animal emotion grows increasingly blurred as evidence accumulates.

These discoveries arrive at a critical moment. Anthropogenic climate change, habitat destruction, and species extinction create unprecedented animal suffering. Populations fragment, disrupting social groups. Extreme weather events kill individuals, leaving survivors to grieve. Ocean acidification and warming threaten marine mammals whose complex societies depend on stable environments.

The science of animal grief reminds us that conservation isn't just about preserving genetic diversity or maintaining ecosystem functions. It's about protecting the capacity for joy, fear, attachment, and sorrow that consciousness enables. When we save a species, we preserve not just bodies but the subjective experiences those bodies contain.

The elephant herd in North Bengal demonstrates this truth. Their burial ritual wasn't mere instinct or mechanical response. It was a community processing loss, honoring a member, and somehow finding meaning in death. In their trumpeting calls and careful earth-scooping, we hear echoes of our own grief - and in that recognition lies the foundation for a more compassionate relationship with the living world we share.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

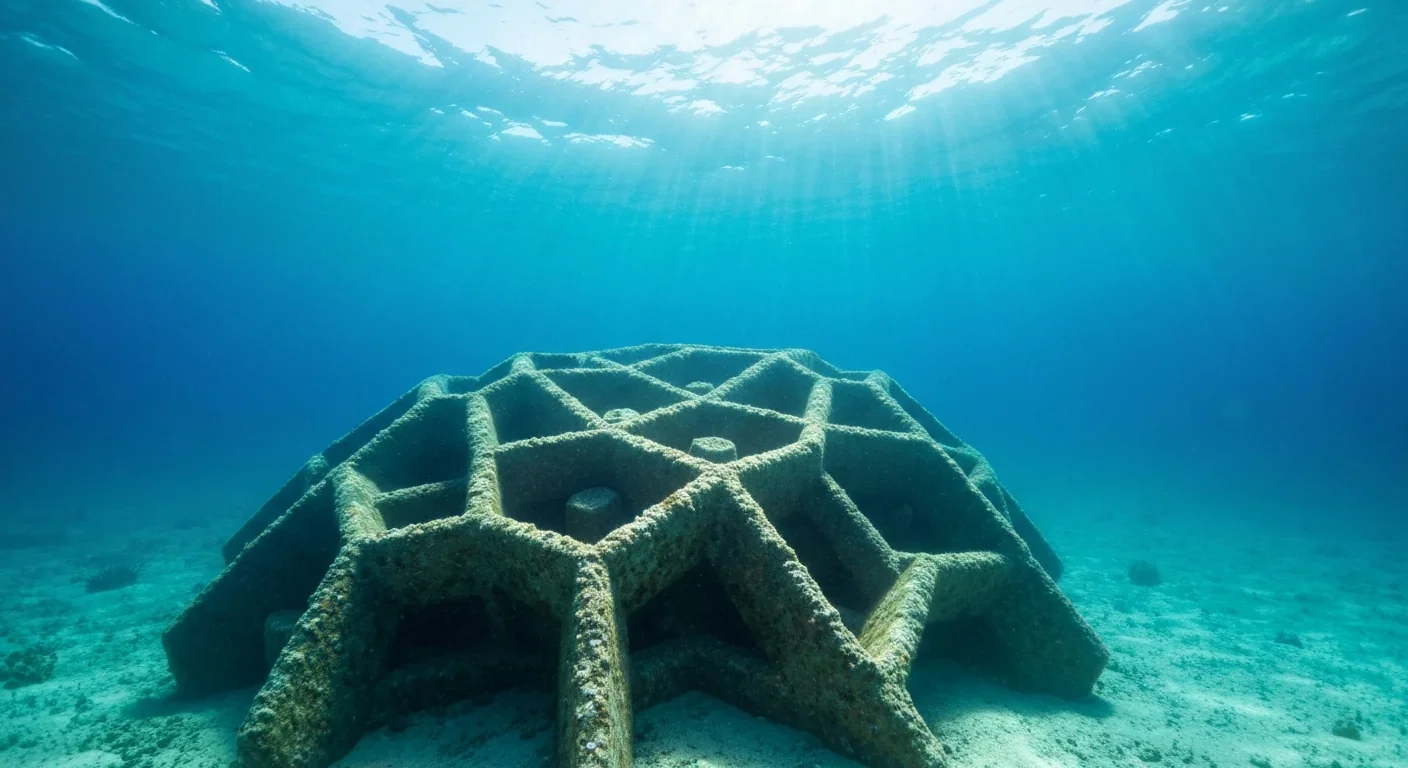

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

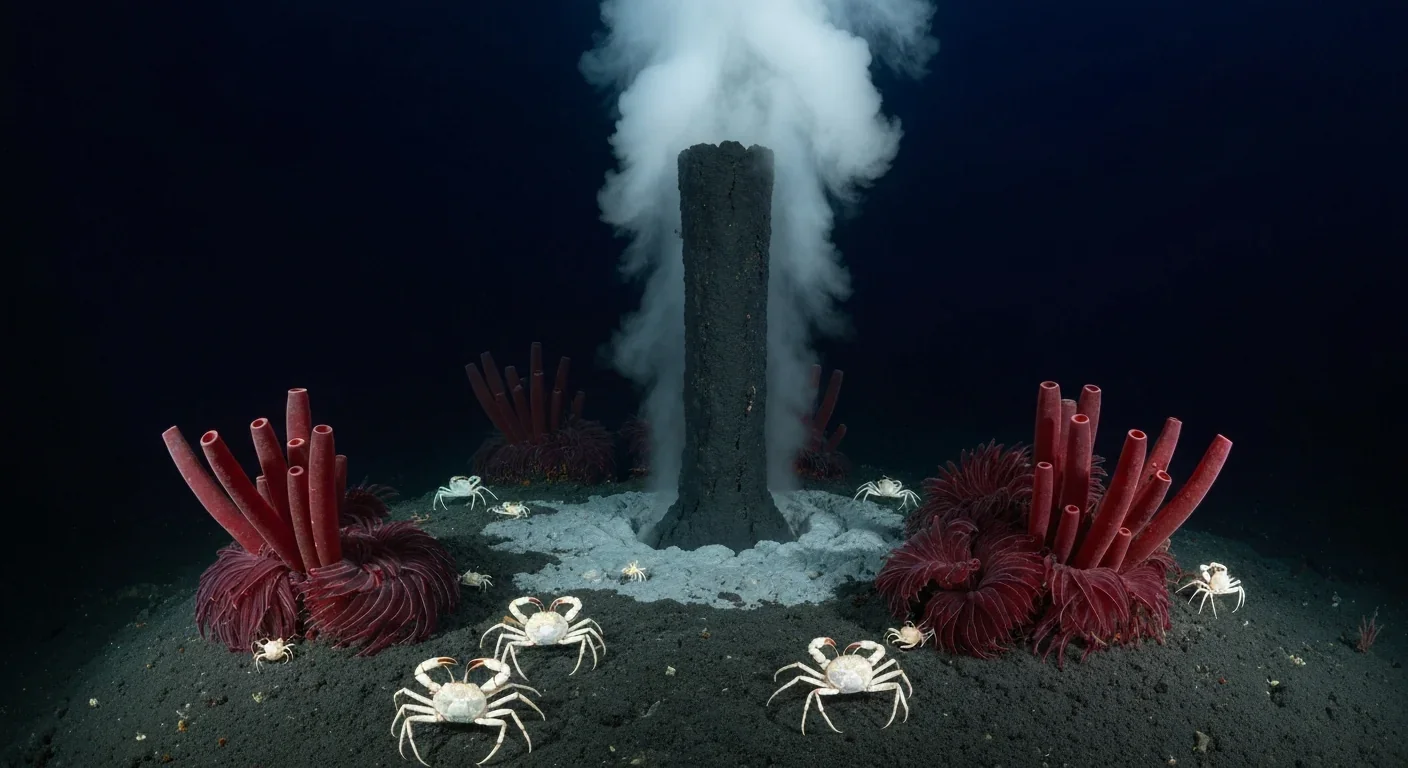

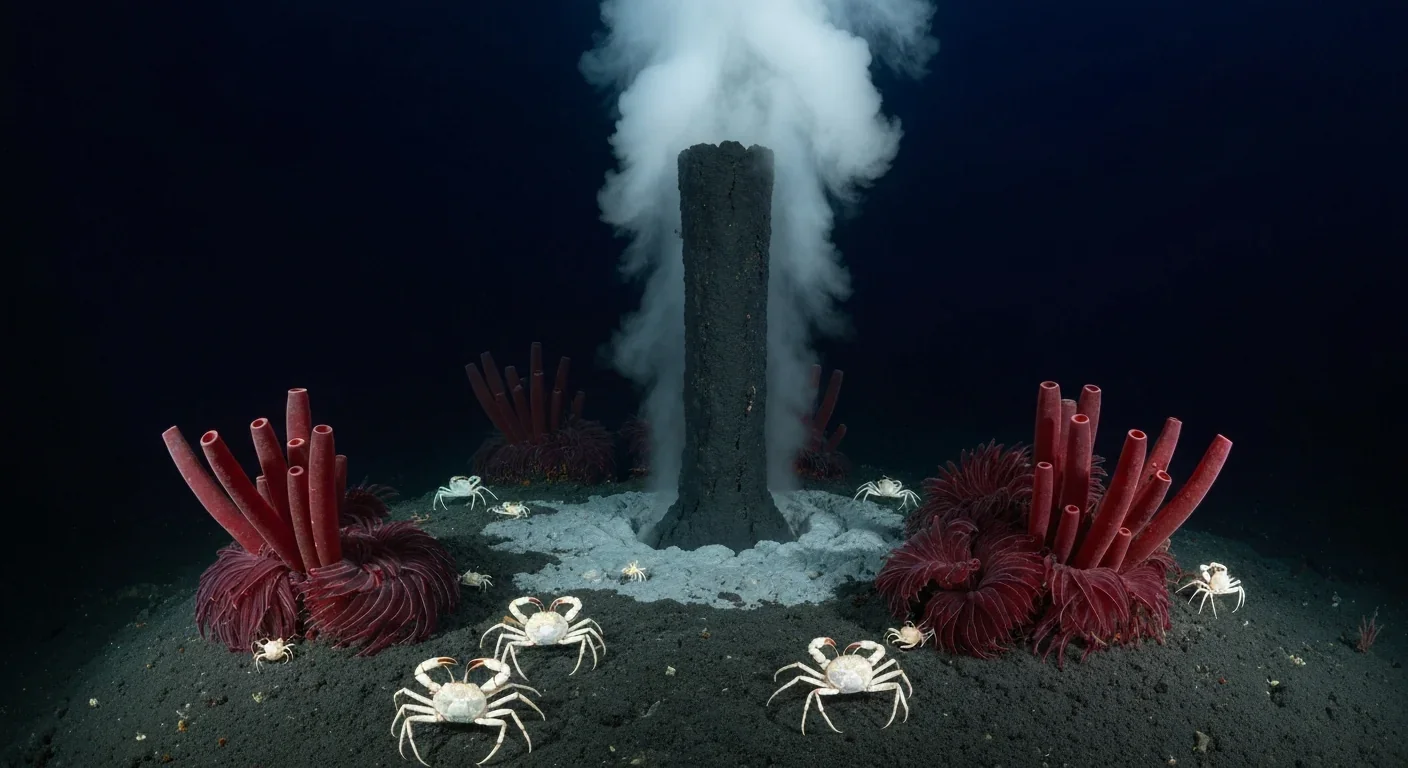

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

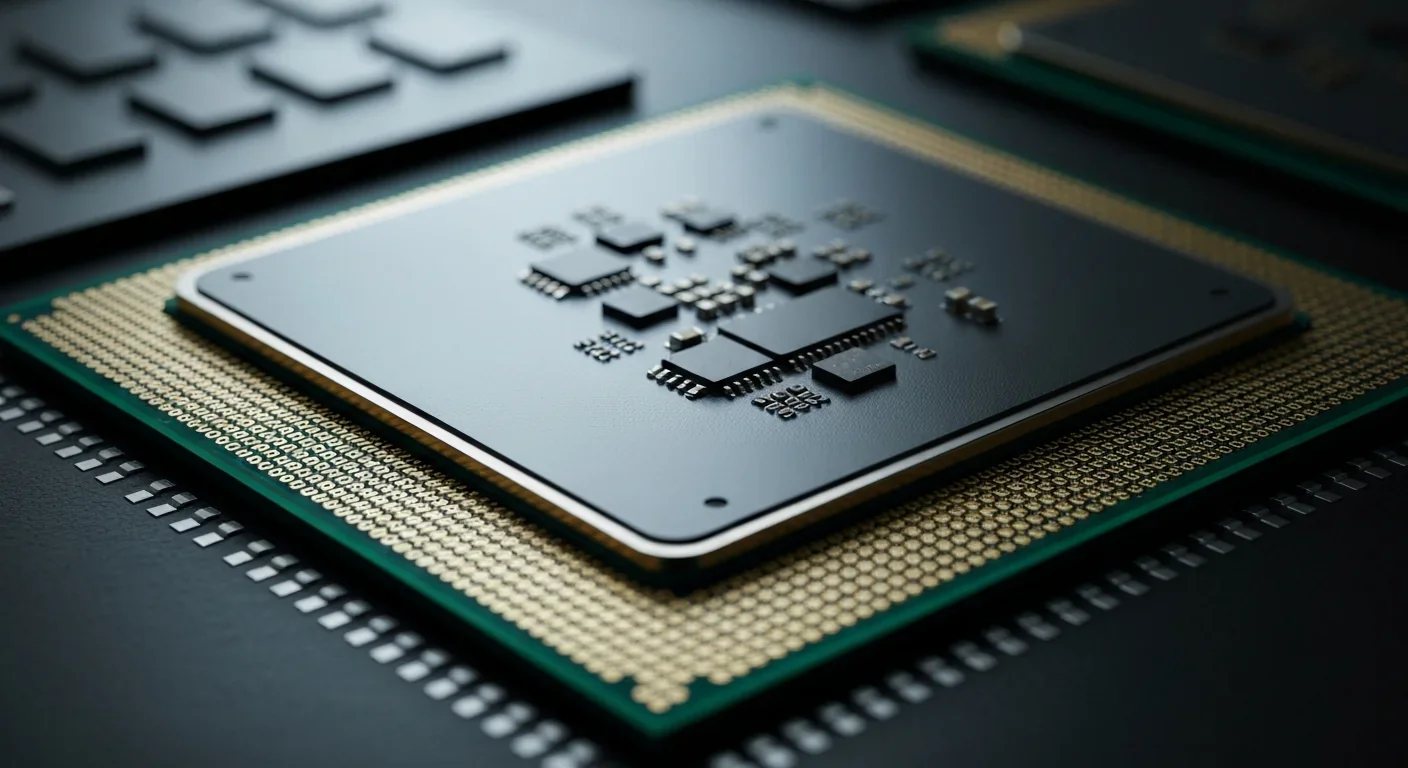

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.