Nature's First Farmers: 50 Million Years of Ant Agriculture

TL;DR: Ancient forests harbor unique bacterial and fungal communities that evolved over centuries. When old-growth forests disappear, we lose not just trees but irreplaceable microscopic ecosystems critical for carbon storage, forest health, and climate regulation - biodiversity that restoration efforts may never fully recover.

By 2050, if current deforestation rates continue, scientists warn we'll have lost not just the trees but entire microscopic civilizations that took centuries to evolve. These hidden bacterial empires - thriving in the bark crevices, roots, and soil of ancient forests - represent biodiversity we're only beginning to understand. And here's the troubling part: once they're gone, we might never get them back.

Walk through an old-growth forest and you're surrounded by giants - trees hundreds, sometimes thousands of years old. What you can't see are the trillions of bacteria coating every surface, orchestrating the forest's invisible economy. These microbial communities are as distinct from young forests as coral reefs are from empty ocean floor.

Old-growth forests harbor microbial communities so specialized that each tree species hosts its own unique bacterial fingerprint. Research from the University of Oregon revealed that 57 different tree species each possessed distinctive leaf bacteria, dominated by core groups including Actinobacteria and various Proteobacteria. It's like each ancient tree operates as its own nation-state, complete with microscopic citizens performing specific jobs.

These aren't random squatters. The bacteria correlate with tree functional traits - growth rate, leaf nitrogen content, nutrient cycling capacity. They're integrated partners, not passengers. Scientists studying Bornean tropical forests found that old-growth forests contained approximately 14,000 bacterial species unique to ancient stands, compared to only 9,479 in naturally regenerating forests and 8,321 in actively restored areas.

Nearly 5,000 bacterial species exist exclusively in old-growth forests. They didn't colonize younger stands. They require centuries of evolutionary time to establish.

The fungal communities tell an even starker story. Total fungal diversity was significantly higher in old-growth forests compared to both logged types, with 7,695 fungal species found only in ancient stands. These fungi form mycorrhizal networks - underground information highways connecting trees, transferring nutrients, water, and even chemical warning signals between individuals.

Age matters, and not just in tree rings. When Japanese researchers analyzed larch plantations ranging from 6 to 51 years old, they discovered that microbial community composition and metabolic activity dramatically shifted with tree age. Young forests featured highly diverse but unstable bacterial communities. As forests matured, diversity initially peaked then gradually stabilized, with communities becoming tighter-knit and more functionally specialized.

The researchers identified keystone bacterial taxa - particularly from the phyla Chloroflexi, Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota, and Nitrospirota - that serve as ecological hubs, maintaining network stability and regulating carbon transformation processes. These keystone species act like infrastructure managers, coordinating thousands of other microbial interactions.

Distance-decay analysis revealed another surprising pattern: bacterial community turnover was higher in old-growth forests than in logged areas. Translation: ancient forest soils are more heterogeneous across small spatial scales - even centimeters apart. This micro-scale diversity creates redundancy and resilience, buffering the ecosystem against disturbances.

Mature forest microbiomes shift their metabolic focus. Near-mature stands excel at processing labile carbon - the easily degradable stuff. But truly ancient forests specialize in breaking down recalcitrant carbon - the tough, chemically resistant compounds that store carbon for centuries if left intact. This specialization has massive implications for climate.

Here's where microscopic life intersects with planetary-scale climate regulation. Soil microbiomes don't just influence carbon storage - they fundamentally control it. Research on Japanese larch plantations showed that soil organic carbon increased from 34.2 g/kg in young stands to 46.7 g/kg in near-mature forests, driven largely by bacterial community shifts.

But the relationship isn't linear. Carbon storage actually declined to 41.3 g/kg in the oldest stands studied, suggesting that very mature forests reach an equilibrium where microbial respiration and decomposition balance new carbon inputs. The real climate value of old-growth microbiomes lies in their ability to process and stabilize recalcitrant carbon - locking it away for geological timescales.

"Methanotrophic bacteria living on boreal trees actively consume atmospheric methane, a greenhouse gas 28 times more potent than CO2 over a 100-year period."

- Woodwell Climate Research Center

Methanotrophic bacteria living on boreal trees offer another climate twist. These methane-eating microbes actively consume atmospheric methane, a greenhouse gas 28 times more potent than CO2 over a 100-year period. Scientists at Woodwell Climate Research Center are studying whether enhancing these bacterial populations could turn forests into even more powerful climate regulators.

Viruses add yet another layer. Recent work on subtropical forest succession revealed that soil viruses drive carbon turnover by infecting bacteria and altering their metabolic functions. As forests age, viral communities shift from DNA viruses to RNA viruses, with different infection strategies that affect how quickly carbon cycles through the system.

The microbial biomass carbon itself represents a significant pool. Studies found that microbial biomass carbon and enzyme activity peaked in near-mature forests, suggesting there's an optimal window where microbial communities are most metabolically active and efficient at carbon processing - neither too young nor too old.

Deforestation destroys trees, obviously. Less obvious: it obliterates microbial communities that may require centuries to re-establish, if they ever do. Research from Sabah, Malaysia compared old-growth forests in the protected Danum Valley with selectively logged forests undergoing restoration since 2000. Almost two decades after logging, bacterial and fungal communities in restored areas remained distinctly different from old-growth reference sites.

The data is sobering: certain microbial attributes remained altered after 19 years of recovery. Both passive regeneration and active enrichment planting failed to restore the original community composition. Active restoration, which involved planting dipterocarp and fruit trees at 3-meter intervals with liana removal, actually pushed mycorrhizal communities further from old-growth conditions than passive regeneration did.

Why? Planted tree species select for mycorrhizal fungi they prefer, overriding the legacy community. It's like renovating an apartment building and evicting long-term tenants who knew all the quirks and plumbing issues. The new residents function, but differently.

This matters because mycorrhizal symbioses are fundamental to forest health. These fungal-root partnerships transfer nutrients - particularly nitrogen and phosphorus - to trees while receiving carbon in return. Different mycorrhizal guilds have different capabilities. Ectomycorrhizal fungi, which dominate many old-growth temperate and boreal forests, access nutrients from organic matter that trees alone cannot reach. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi excel at mobilizing phosphorus from mineral soil.

When logging disrupts mycorrhizal partnerships, trees become nutrient-stressed, growth slows, and the forest's capacity to sequester carbon diminishes - effects that cascade through the entire ecosystem.

When logging disrupts these partnerships, the effects cascade. Trees become nutrient-stressed, growth slows, and the forest's capacity to sequester carbon diminishes. Research on temperate forests showed that bacterial and fungal communities exhibit distinct long-term responses to disturbance, with recovery trajectories measured in decades for bacteria and potentially longer for fungi.

Post-fire recovery offers another cautionary tale. Studies of microbial succession after wildfire found that while some bacterial groups recolonize quickly, the functional composition takes years to stabilize. Fire-adapted communities evolved with natural fire regimes, but high-severity modern wildfires - exacerbated by climate change and fire suppression - create conditions outside evolutionary experience.

Scientists recently mapped something even more hidden: microbiomes living inside tree trunks. Using DNA sequencing techniques, researchers discovered diverse bacterial and fungal communities inhabiting the heartwood, sapwood, and bark tissues. These weren't contaminants from external surfaces - they were endophytes, microbes living within plant tissues.

Some of these endophytic bacteria produce antimicrobial compounds that protect trees from pathogens. Others fix nitrogen, essentially fertilizing their host from within. Still others produce plant growth hormones that enhance tree vigor and stress tolerance. It's symbiosis at its most intimate - bacteria and fungi so integrated into tree biology that defining where "tree" ends and "microbe" begins becomes philosophically murky.

Old-growth trees accumulate these endophytic communities over centuries, creating internal ecosystems as complex as the external ones. When a 500-year-old tree falls, it takes its internal microbiome with it. And because endophyte transmission often occurs vertically - parent trees inoculating offspring - losing ancient trees can break chains of microbial inheritance that stretch back generations.

Research on sugar maple phyllosphere and rhizosphere revealed that leaf surfaces and root zones host overlapping but distinct microbial communities. The phyllosphere - leaf surface microbiome - changes seasonally, responding to temperature, humidity, and UV exposure. The rhizosphere - root zone - remains more stable but interacts dynamically with soil microbes and mycorrhizal networks.

Both zones play roles in tree immunity. Leaf bacteria compete with pathogenic fungi for space and resources. Root microbes solubilize minerals, produce antibiotics against soil-borne diseases, and can even prime tree defenses through induced systemic resistance. When we lose old-growth forests, we lose these finely tuned protection systems - evolved partnerships that new plantings take decades or centuries to rebuild.

This is the uncomfortable question forestry faces. Restoration ecology traditionally focused on aboveground metrics: canopy cover, tree species diversity, basal area. Below ground received less attention because soil microbiomes were invisible and difficult to quantify. Now that sequencing technology reveals what we're missing, the scale of the challenge becomes clear.

Brazilian biome research using metagenomic analysis across diverse ecosystems revealed that soil microbial diversity and functionality vary dramatically between biomes and disturbance histories. Attempting to restore one biome using microbial inoculum from another would be like performing an organ transplant without matching tissue types - rejection likely.

Some restoration efforts are trying targeted microbial interventions. Soil microbiome research suggests that inoculating planting sites with old-growth soil could accelerate community recovery. The challenge: old-growth soil is rare and removing it damages the reference ecosystem. Creating synthetic inoculum - cultivating key microbial consortia in labs - remains technically difficult because most soil microbes resist cultivation.

Active restoration impacts microbiomes in complex ways. The Bornean study found that enrichment planting altered mycorrhizal community composition, potentially selecting for different microbial assemblages than passive regeneration. This doesn't mean active restoration is bad - it successfully accelerates tree biomass recovery - but it follows a different ecological trajectory than natural succession.

Researchers studying Phoebe bournei forests in subtropical China found that forest succession improves both the complexity of soil microbial interactions and the ecological stochasticity of community assembly. Mature forests feature more intricate microbial networks with greater functional redundancy, making them more resilient to environmental fluctuations. Younger forests, even decades into recovery, remain more vulnerable to community disruption from droughts, temperature extremes, or pollution.

"Time appears to be the irreplaceable ingredient. Even with perfect soil conditions, optimal tree species, and favorable climate, microbial communities need decades to achieve the network complexity and functional specialization of true old-growth."

- Forest Restoration Research

Time appears to be the irreplaceable ingredient. Even with perfect soil conditions, optimal tree species, and favorable climate, microbial communities need decades to achieve the network complexity and functional specialization of true old-growth. A study of forest restoration metrics found early evidence that soil microbes correlate with multiple ecosystem recovery indicators, suggesting microbial composition could serve as a sensitive metric for assessing restoration success.

The technological revolution enabling this research deserves recognition. High-throughput DNA sequencing - particularly 16S rRNA sequencing for bacteria and ITS sequencing for fungi - allows researchers to identify thousands of microbial species from a single soil sample without culturing them. This matters because 99% of soil microbes cannot be grown in lab culture using standard techniques.

Metagenomic sequencing goes further, reconstructing entire microbial genomes from environmental samples. This reveals not just who's present but what they're capable of doing - which enzymes they produce, which metabolic pathways they possess, how they might respond to environmental changes. The Brazilian metagenomic study used this approach to bridge gaps in understanding soil microbial diversity and functionality across biomes.

Network analysis techniques borrowed from social science - originally designed to map human relationships - now map microbial interactions. Molecular ecological network (MEN) analysis identifies keystone taxa that maintain community stability, similar to how removing certain people from a social network causes the group to fragment. The Japanese larch study used MEN to reveal that Chloroflexi consistently served as network hubs across all forest ages.

Isotope tracing follows carbon and nitrogen through ecosystems, revealing who eats what and how energy flows through microbial food webs. Researchers can now track individual carbon atoms from atmospheric CO2 through photosynthesis into tree tissues, then into root exudates that feed bacteria, which are then consumed by protozoa, and so on through multiple trophic levels.

Viruses in soil - an entire realm barely studied until recently - are now being characterized through viral metagenomics. The subtropical forest succession study identified thousands of viral species and showed they actively structure bacterial communities by selective infection. This adds another dimension: microbial communities aren't just shaped by competition and mutualism but by top-down viral predation.

Advances in bioinformatics handle the data deluge. A single soil metagenome might contain billions of DNA sequences requiring assembly, annotation, and functional prediction. Machine learning algorithms now predict microbial functions, ecological interactions, and even responses to climate change based on genomic content. These computational tools transform raw sequence data into ecological insight.

Forest ecosystems would still exist. Trees would grow. But functionality would degrade in ways we're only beginning to quantify. Think of it as the difference between a building with experienced maintenance staff who know every system intimately versus a new crew following generic manuals. Things mostly work, but inefficiencies accumulate, minor problems escalate, and the whole operation becomes less resilient.

Specific losses would include reduced carbon sequestration capacity - both because fewer specialized bacteria break down recalcitrant carbon and because disrupted mycorrhizal networks deliver nutrients less efficiently, slowing tree growth. Forests would become more vulnerable to pathogens and pests as protective endophytic and rhizosphere bacteria disappeared. Nutrient cycling would slow, potentially leading to nutrient limitation even in otherwise fertile soils.

Water regulation might suffer. Mycorrhizal networks help trees access water during droughts, essentially extending root systems through fungal hyphae that can penetrate soil pores too small for roots. Drought mitigation research found that long-term drought changes the functional potential and life-strategies of forest soil microbiomes involved in organic matter decomposition, with cascading effects on ecosystem services.

Unlike cutting down the last tree of a species - a clear, visible extinction - microbial extinctions happen silently. We might lose hundreds of bacterial species without noticing until ecosystem functions they supported began failing years or decades later.

The loss would be cumulative and largely invisible. Unlike cutting down the last tree of a species - a clear, visible extinction - microbial extinctions happen silently. We might lose hundreds of bacterial species without noticing until ecosystem functions they supported began failing years or decades later. By then, reintroduction might be impossible if we never cultured the extinct species and don't have preserved genetic material.

Indigenous communities who have stewarded old-growth forests for millennia understood intuitively what science is now confirming: these ecosystems are integrated wholes where above and below ground are inseparable. Degrading forests lose soil quality as microbes disappear, creating a downward spiral where poor soil supports fewer trees, which further degrades the remaining microbial community.

Conservation priorities need to expand beyond charismatic megafauna and impressive trees to include the invisible majority. Protecting old-growth forests preserves not just timber and wildlife habitat but irreplaceable microbial diversity. Current protected area networks rarely consider belowground biodiversity in designation decisions. That needs to change.

Restoration strategies should incorporate microbial ecology from the start. Instead of simply planting trees and hoping for the best, future efforts might include soil microbiome assessments, targeted microbial inoculation, and monitoring of below-ground recovery alongside above-ground metrics. Research on mycorrhizal symbioses in ecological restoration provides frameworks for integrating fungal partners into restoration planning.

Forest management in working landscapes could adopt practices that maintain microbial diversity. Selective logging that preserves some old trees might retain inoculum sources for regenerating stands. Longer harvest rotations would allow more microbial community development between cuts. Retaining woody debris provides habitat for decomposer communities that build soil carbon.

Urban forestry offers unexpected opportunities. Research on bacteria on old-growth trees suggests that even urban trees can host beneficial microbiomes if we protect older trees and maintain soil quality. Cities could serve as refugia for some microbial diversity as rural forests face pressure.

Scientific priorities should include cataloging microbial diversity before it disappears. A microbial equivalent of seed banks - culture collections and cryopreserved soil samples from threatened old-growth forests - would preserve genetic material for future restoration. Given that most soil microbes resist cultivation, preserving actual soil might be more practical than trying to culture individual species.

International cooperation matters because old-growth forests are globally distributed and threats are universal. The role of soil bacteria in nutrition extends beyond forests to agriculture, meaning insights from forest microbiome research can inform sustainable farming practices, creating broader constituencies for protection.

The next time you walk through any forest - ancient or recovering - remember: you're surrounded by civilizations as complex as any coral reef, as specialized as any rainforest canopy, yet invisible to the naked eye. These bacterial and fungal communities represent billions of years of evolution, centuries of local adaptation, and ecological functions we're only beginning to understand.

We're in a strange moment: advanced enough to detect and characterize these hidden worlds, but still destroying them faster than we can study them. The question isn't whether old-growth microbiomes matter - the evidence increasingly shows they do, for carbon storage, forest health, ecosystem resilience, and services we likely haven't discovered yet. The question is whether we'll choose to protect them before they disappear.

Every ancient tree felled doesn't just remove timber. It dismantles centuries-old microbial networks, extinguishes specialized bacterial lineages, and simplifies ecosystems in ways that might be irreversible within human timescales. The microscopic worlds we're losing contain solutions to problems we haven't yet recognized - climate regulation strategies, disease resistance mechanisms, nutrient cycling innovations that could inform everything from forestry to agriculture to bioremediation.

What's happening beneath our feet in remaining old-growth forests may be as important to planetary health as what's happening in the canopy above. These hidden communities deserve the same protection, study, and respect we afford to visible biodiversity. Because once you lose a microbial community that took 500 years to evolve, you can't just plant it back.

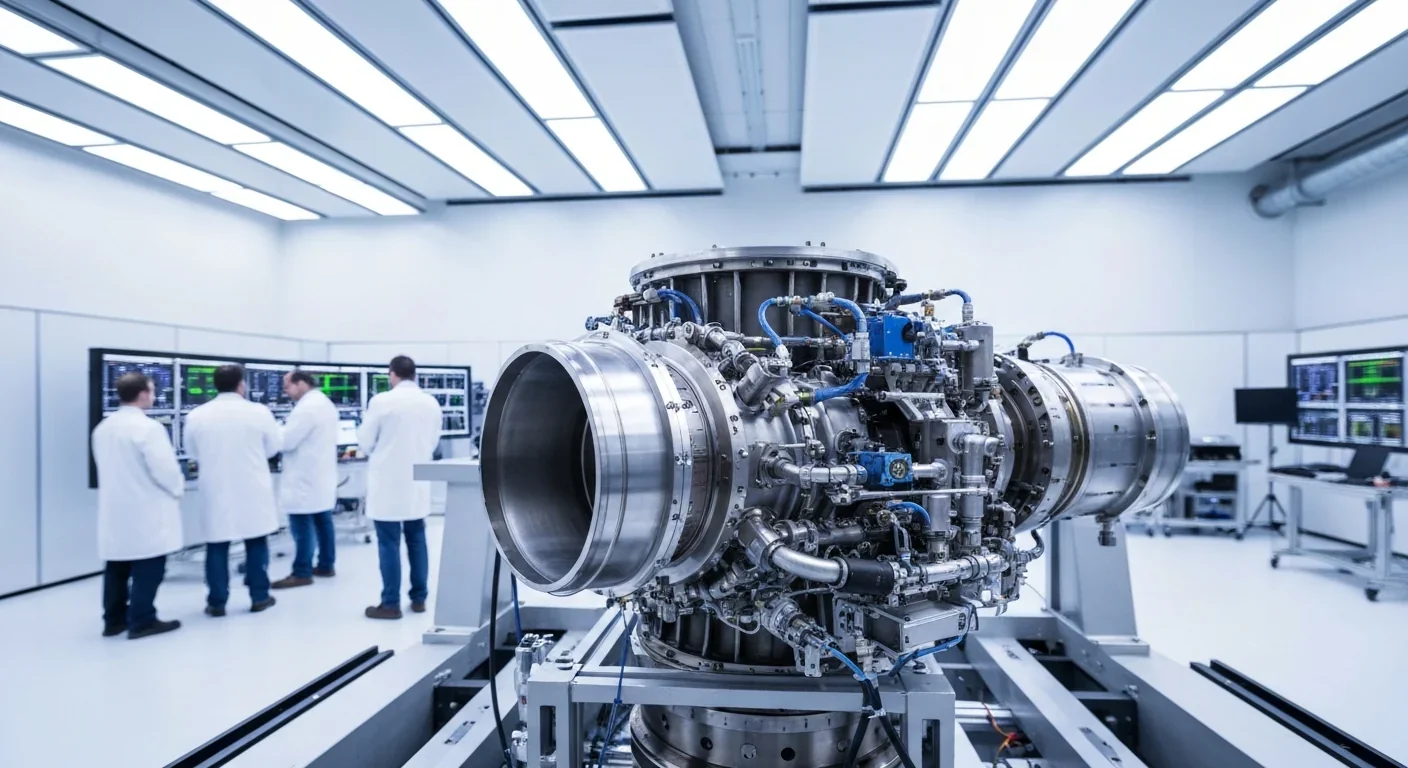

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

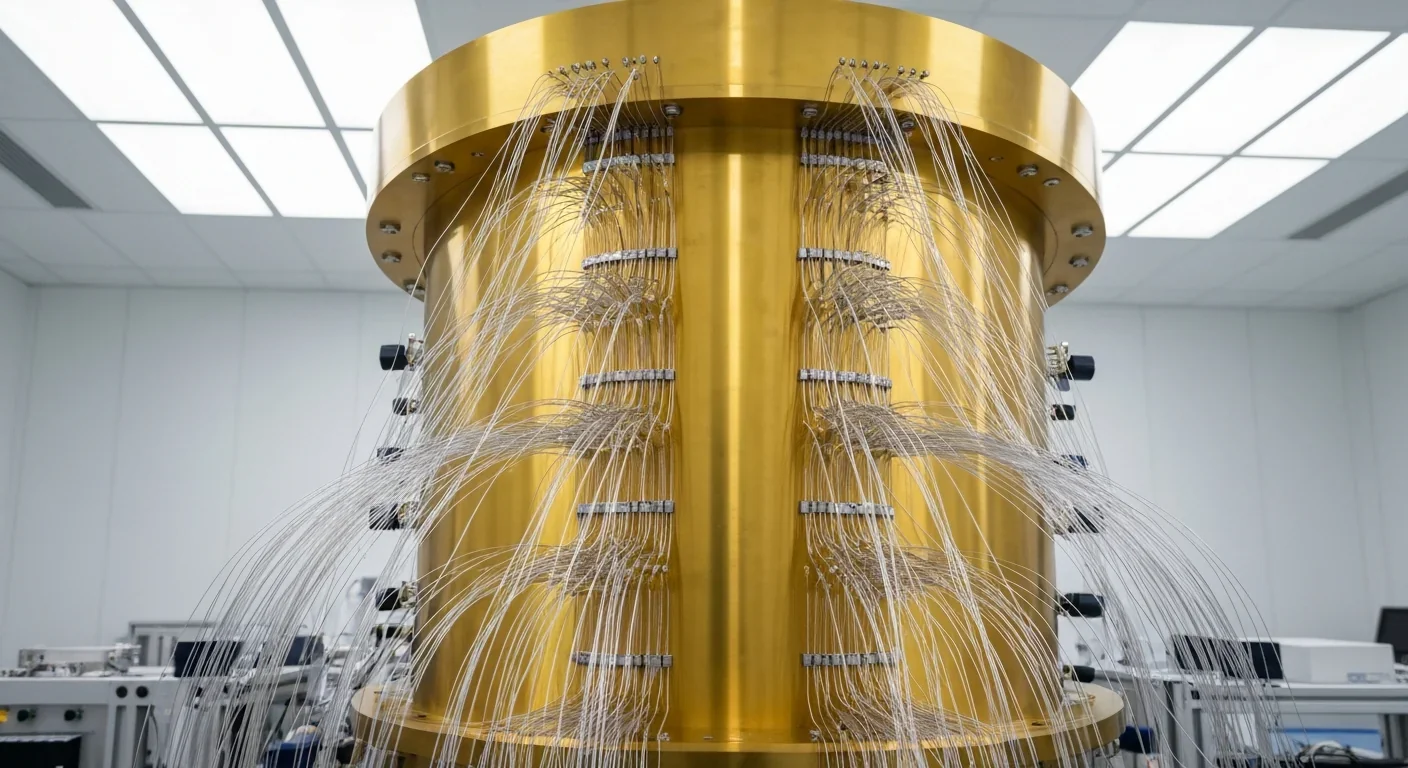

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.