Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Dead trees, or 'zombie wood,' are biodiversity hotspots supporting up to 40% of forest wildlife through five distinct decomposition stages spanning 100+ years. While forest management often removes deadwood, research shows these structures are crucial for carbon storage, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem resilience.

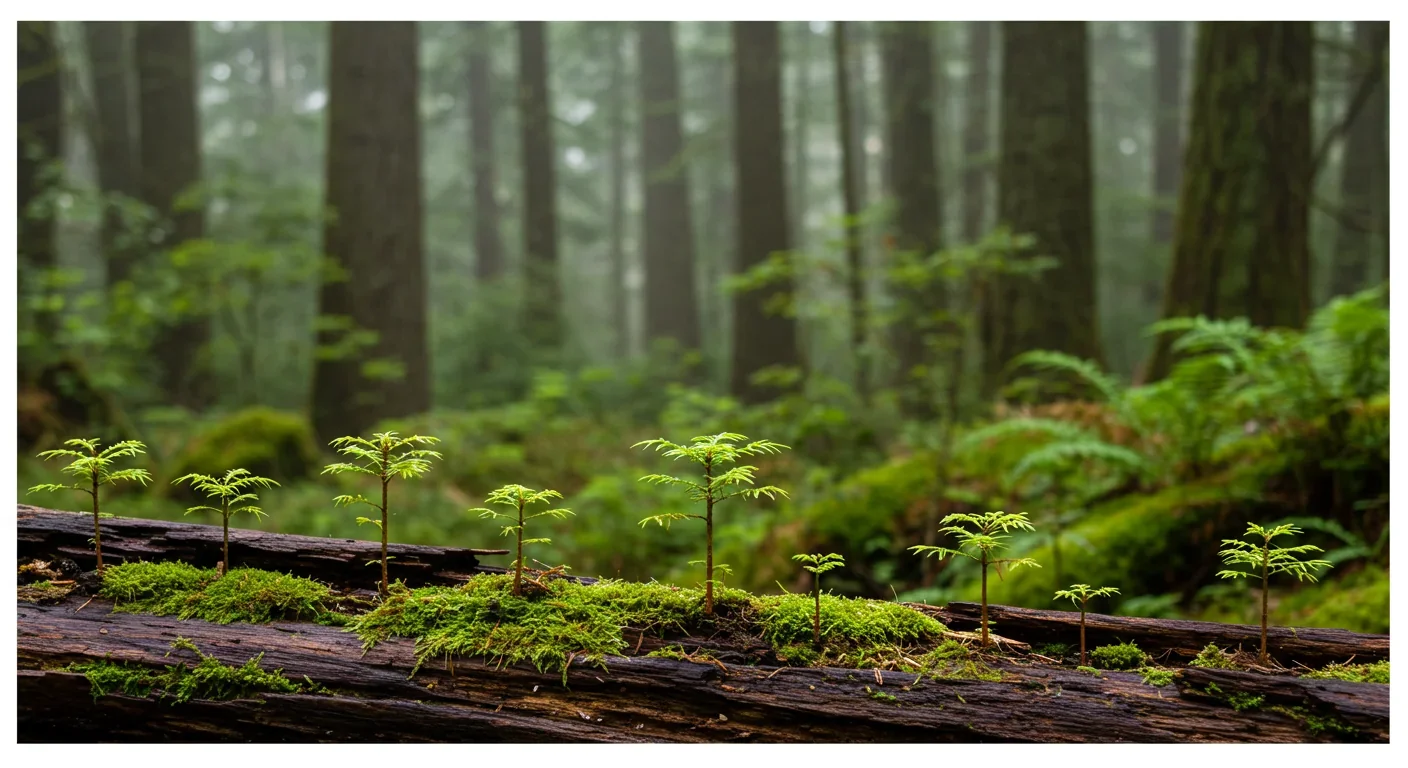

Walk through any forest and you'll see them everywhere: fallen logs slowly dissolving into the earth, standing snags with peeling bark, massive stumps blanketed in moss. Most people see decay. Ecologists see biodiversity hotspots more crowded than a Manhattan apartment building.

Dead wood, increasingly called "zombie wood" by researchers, might be lifeless in name only. These decomposing structures harbor more species per square meter than the living trees around them. In temperate forests, coarse woody debris can make up thirty percent of all woody biomass, creating an entire parallel ecosystem that most of us walk right past without a second glance.

Here's what surprises people: up to forty percent of all forest fauna depend on coarse woody debris at some stage of their lives. That rotting log you stepped over? It's housing fungi, beetles, salamanders, woodpeckers, and dozens of other species all at once - each using different decay stages, moisture levels, and microhabitats within the same piece of wood.

The problem is we've spent centuries removing deadwood from forests, treating it like waste rather than infrastructure. We're only now realizing what we've been taking away.

Dead wood doesn't just rot - it transforms through distinct stages, each creating different habitat conditions. Think of it like neighborhoods in a city: different species move in and out as the character of the place changes.

Stage 1: Fresh Dead Wood (Years 0-3)

When a tree first dies, its bark remains tight and its wood is hard. Early colonizers arrive quickly. Bark beetles tunnel elaborate galleries beneath the surface, creating pathways that will later serve other species. Woodpeckers hammer holes to reach the insects, excavating cavities that will become homes for dozens of bird and mammal species. In Florida alone, twenty-five bird species require dead branches or rotting cavities for nesting, including pileated woodpeckers and white-breasted nuthatches.

The wood at this stage still contains most of its structural strength. It's firm enough to support heavy animals but damaged enough to provide entry points. Owls, kestrels, and flying squirrels take over abandoned woodpecker holes. These secondary cavity nesters depend entirely on birds like woodpeckers to create housing - they can't excavate their own.

In temperate forests, up to 40% of all wildlife depends on dead wood at some stage of their life cycle - making it more biodiverse per square meter than living trees.

Stage 2: Fungi Invasion (Years 3-10)

As moisture penetrates deeper, fungi begin their real work. White-rot fungi attack lignin - the compound that makes wood rigid - using specialized enzymes called peroxidases and laccases. Brown-rot fungi take a different approach, targeting cellulose and leaving the wood dry and crumbly. This chemical warfare changes everything about the log's physical properties.

The bark starts loosening, creating humid pockets between wood and bark. These spaces become salamander apartments and insect nurseries. Central European forests support 1,340 beetle species that depend on deadwood - many specialized for specific decay stages, wood types, and even particular fungal species.

Some beetles have evolved such tight relationships with fungi that they farm them. They carry fungal spores in special pouches, inoculating new wood to cultivate food for their larvae. It's underground agriculture that's been running for millions of years.

Stage 3: Soft Rot and Structural Change (Years 10-25)

Now the log is noticeably softer. You can push your finger into it. Inside, moisture content can reach eighty percent or higher, making these logs crucial water reservoirs during dry seasons. This moisture buffer helps seedlings survive drought - a service that becomes more valuable as climate patterns shift.

The log's interior becomes a maze of galleries, chambers, and passages. Carpenter ants establish massive colonies, their excavations creating even more habitat complexity. Some rare beetles like the alpine longhorn beetle (Rosalia alpina) need exactly this stage - old, splintered trunks of specific tree species. Their larvae spend three years developing inside the wood, which means they need logs that will stay put for at least that long.

"By providing both food and microhabitats for many species, coarse woody debris helps to maintain the biodiversity of forest ecosystems."

- Wikipedia, Coarse Woody Debris

This is where forest management often goes wrong. Many threatened beetle species are disappearing not because their forests are vanishing, but because dead trees are being removed before larvae can complete development. The wood looks ready for firewood, but from an ecological perspective, it's an active maternity ward.

Stage 4: Advanced Decomposition (Years 25-50)

The log starts fragmenting. Pieces break off easily. Mosses and lichens blanket the surface, adding another layer of habitat. These bryophyte communities create micro-gardens where tree seedlings can germinate away from the competitive forest floor.

This is the "nurse log" phase that's famous in old-growth forests. Seedlings sprout in rows along fallen trunks, their roots reaching down into the decaying wood for nutrients. In Pacific Northwest rainforests, you see entire groves of towering trees aligned in perfectly straight rows - all germinated on the same fallen giant, now completely decomposed and invisible.

The nutrient transfer happening here is extraordinary. Decomposing wood releases nitrogen, phosphorus, and dozens of other compounds back into the ecosystem slowly, over decades. This prevents nutrient pulses that might favor aggressive species while starving slower-growing natives. It's a time-release fertilizer system engineered by evolution.

Stage 5: Integration (Years 50-100+)

Eventually, the log becomes difficult to distinguish from the surrounding soil. But it's still there, still functioning. The remaining wood fragments continue hosting specialized decomposers - springtails, mites, nematodes, and bacteria - that complete the final transformation to humus.

Here's something that surprised researchers: decomposition rates vary by a factor of 244 across species and climates. A pine log might break down in twenty years in a warm, moist forest but persist for a century in a cool, dry environment. This variability means different forest types have radically different deadwood ecologies, each supporting specialized communities.

For decades, foresters argued that removing dead wood was good for forests because decomposing logs release carbon dioxide. Take the carbon out as timber, the thinking went, and you help climate.

That calculation misses most of what's actually happening. Yes, decomposition releases CO₂, but it also transfers massive amounts of carbon into soil storage where it can remain for centuries. Fungi don't just break down wood - they move carbon compounds deep into soil layers where different decomposition chemistry takes over.

In old-growth Douglas-fir forests of the Pacific Northwest, CWD concentrations range from 72 to 174 metric tons per hectare. These aren't static storage pools - they're actively moving carbon through the ecosystem, feeding soil food webs, supporting plant growth, and maintaining forest resilience.

Studies comparing forests with different structural complexity show that forests with more deadwood store more carbon overall, not less. The living trees grow better because soil conditions are richer, moisture availability is more stable, and the entire system is more productive.

Forests with higher deadwood volumes actually store MORE total carbon than "tidier" managed forests - the decomposing wood feeds soil systems that boost living tree growth.

When you remove deadwood, you're not just taking away habitat - you're interrupting carbon cycles that have been optimizing for thousands of years.

The ecology of decomposition changes dramatically depending on where you are. In European beech forests, coarse woody debris averages 40-70 cubic meters per hectare. In other Central European forests, it reaches 100-180 cubic meters per hectare. These differences reflect climate, tree species, disturbance history, and management practices.

Tropical forests face a completely different situation. High temperatures and moisture mean wood decomposes rapidly - sometimes within a decade. The species communities are adapted to this pace, with fungi and termites breaking down massive trunks so quickly that the slow decomposers common in temperate forests can't compete.

Boreal forests at the other extreme. Cold temperatures slow everything down. A log that would rot in twenty years in Pennsylvania might persist for eighty years in northern Canada. This creates unique problems: when climate warms, decomposition rates accelerate, releasing carbon faster than the ecosystem has historically cycled it.

What worries ecologists is that species adapted to century-long decomposition timelines might not keep pace with accelerating change. Specialized beetles that need forty years to complete multiple generations in a single log could find their habitat disappearing faster than they can adapt.

Visit a managed forest and a wilderness area in the same region. The difference is stark. Managed forests look clean, organized, almost park-like. Wilderness areas look chaotic - logs piled everywhere, snags standing like sentinels, branches and debris coating the ground.

Which is healthier? The chaotic one, by almost every ecological measure.

The impulse to tidy forests is strong. Dead wood looks untidy. It creates obstacles. It supposedly increases fire risk. So forest managers remove it, selling what they can as firewood or chips and burning the rest.

But research comparing tidied and untidied forests tells a different story. After major storms like Vivian (1990) and Lothar (1999) in Switzerland, areas left uncleared showed higher insect diversity, especially for longhorn and jewel beetles. The total number of insects was similar in cleared and uncleared areas, but the species composition shifted dramatically.

What disappeared with the deadwood? Specialists. Species that evolved tight dependencies on specific decay stages, wood types, and associated fungi. They're replaced by generalists - species that do fine in disturbed habitats and don't need old forests.

"Whole-tree harvesting is likely to be the main trigger for a decline in deadwood volumes."

- waldwissen.net, Energy Wood and Saproxylic Species

You still have a forest. You still have insects. But you've lost ecological complexity, replacing a specialized workforce with flexible generalists. Over time, this erodes the ecosystem's ability to respond to change.

Here's where it gets complicated: deadwood does increase fire risk in some contexts. Logs and branches are fuel. In fire-prone landscapes, decades of fire suppression have created unnaturally high fuel loads. When fires finally come, they burn hotter and more destructively than historical fires would have.

Should managers remove deadwood to reduce fire risk? The answer depends on the forest type and fire regime. In ecosystems adapted to frequent, low-intensity fires (like ponderosa pine forests in the American West), reducing fuel loads makes sense. But even there, you can't remove everything without harming species that depend on deadwood.

The solution involves strategic retention: leave snags standing away from structures, maintain scattered deadwood in varied decay stages, and focus removal on areas with genuinely dangerous fuel accumulation. It's more complex than either "leave it all" or "remove it all," which means it requires actual forestry expertise rather than simple rules.

In ecosystems with historically infrequent, high-severity fires (like coastal rainforests), deadwood isn't a significant fire risk. Removing it provides no fire benefit while causing substantial ecological harm.

Unfortunately, management policies often treat all forests the same, applying fire-reduction strategies even where fire risk is minimal.

If you own forest land, you have direct power to support deadwood ecology. The recommendations are surprisingly simple:

Leave standing dead trees (snags) unless they pose immediate danger to people or structures. Studies from Bavaria show that increasing deadwood by just 1-3 percent doubles cavity-nesting bird populations. You don't need to transform your forest into a snag field - small increases make big differences.

Retain fallen logs in various decay stages. Aim for a mix: some fresh, some advanced, some nearly soil. This supports the full range of species. If you must remove some for access or safety, leave the rest where they fall.

Don't rush to "clean up" after storms. Windthrow events create valuable habitat pulses. Unless you have immediate timber salvage value or fire concerns, leaving storm-damaged trees where they fall benefits hundreds of species.

Consider creating artificial snags in younger forests that lack natural deadwood. You can girdle selected trees (removing a ring of bark to kill them while leaving them standing) or use woodpecker poles - sections of dead trees anchored vertically in the ground.

Diversify tree species if you're planting. Different species decompose at different rates and support different communities. Beech, oak, pine, and fir each have specialized associates that depend on their particular wood chemistry.

A simple 1-3% increase in deadwood can double bird populations in managed forests - you don't need wilderness conditions to make a significant biodiversity difference.

Think in decades, not seasons. Deadwood ecology operates on long timeframes. Management decisions you make now will shape habitat availability for decades. That's intimidating, but it also means your choices have lasting impact.

The long-term research station at Andrews Experimental Forest in Oregon has been studying the same fallen logs since 1985. These datasets are invaluable because decomposition is so slow you need decades of monitoring to understand patterns.

In 2023, seventy percent of the Andrews watershed burned, destroying three of six decomposition research sites. It was a catastrophic loss of irreplaceable data, but it also demonstrated exactly what researchers have been worried about: changing climate is disrupting ecological processes that operate on century timescales.

Warmer temperatures accelerate microbial activity, speeding decomposition. More variable precipitation means logs dry out faster between rain events, changing fungal communities. More severe storms create sudden pulses of deadwood that overwhelm decomposer communities.

These shifts create mismatches. Species adapted to slow, predictable decomposition find their habitat disappearing faster than they can disperse to new sites. Fungi that need specific moisture regimes face conditions outside their tolerance ranges. The intricate timing that evolved over millennia starts breaking down.

What can forests do? The systems with the best chance are those with high diversity - many species, many deadwood types, many decay stages all present simultaneously. Diverse systems have redundancy. When one species fails, others can fill its role. Simplified, tidied forests lack that resilience.

We're living through a shift in how we understand forests. For most of industrial forestry's history, forests were viewed as wood factories. Trees were the product. Everything else was waste or obstacles to production.

That view is changing, but slowly. We now recognize forests as ecosystems providing dozens of services: carbon storage, water filtration, biodiversity habitat, recreation, and yes, timber. Deadwood contributes to nearly all of those except timber, and even there it plays a role by improving long-term site productivity.

The challenge is that ecological benefits from deadwood are diffuse and long-term, while costs are immediate and obvious. A landowner who retains snags sees dead trees taking up space. The woodpeckers, salamanders, fungi, and beetles benefiting are mostly invisible. The improved soil moisture and nutrient cycling won't be obvious for decades.

This is where policy matters. European countries increasingly require deadwood retention in managed forests - specified volumes per hectare in various decay stages. It's not left to individual choice but mandated as part of sustainable forestry.

North American forestry is patchier. Some regions have strong protections. Others leave it entirely to landowner discretion. Given that forests with deadwood have twenty-three percent more biodiversity than those without, this isn't a minor detail.

"Deadwood is a component of healthy woodland ecosystems and provides a suite of unique ecological niches."

- Forest Research, UK

The science is clear: dead wood is fundamental forest infrastructure. What we call "zombie wood" is more alive than the name suggests - teeming with organisms, cycling nutrients, storing carbon, creating habitat, and maintaining ecological processes that living trees depend on.

We spent centuries trying to eliminate it. Now we need to bring it back - or in wilderness areas, just leave it alone. The "untidy" forest is the functional forest. The dead wood is the living heart of forest biodiversity.

Next time you step over a rotting log, look closer. Peel back some bark. Check for galleries and holes. Notice the moss. You're not looking at death - you're seeing one of the most biodiverse structures in the entire forest.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

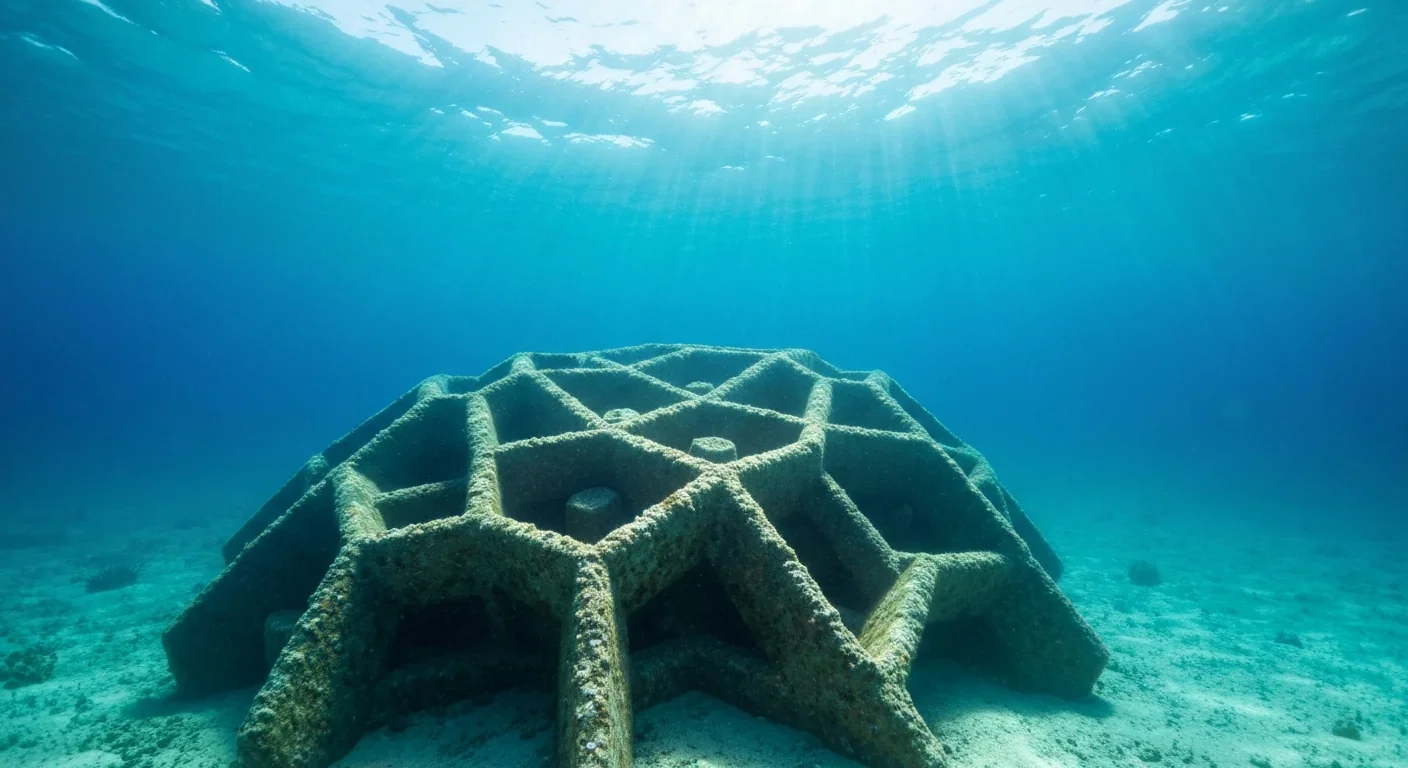

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

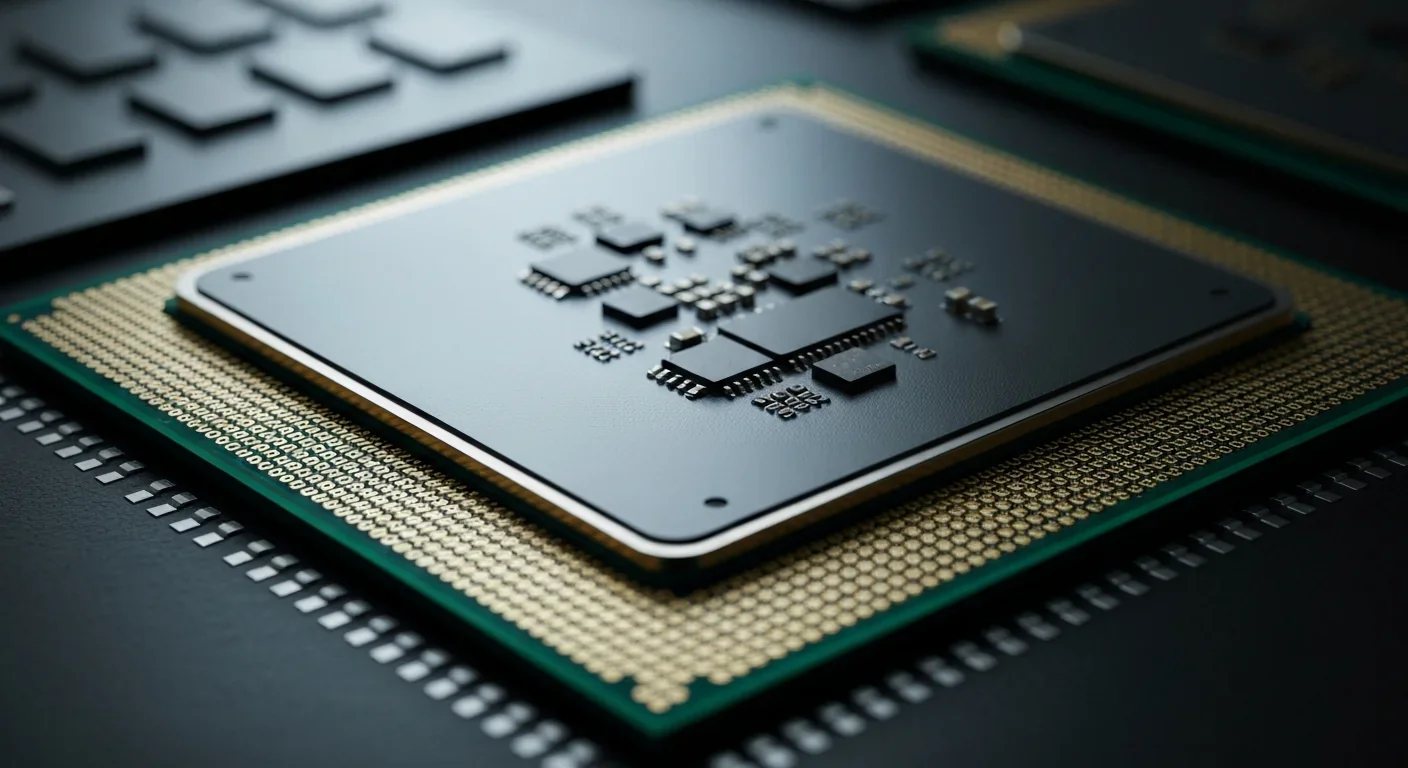

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.