Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: In nature's partnerships, cooperation isn't guaranteed. Emerging research reveals that symbionts from bacteria to cleaner fish routinely cheat their partners when conditions make exploitation more profitable than cooperation, reshaping our understanding of how cooperation really works.

In every partnership, someone is always running the numbers. Cost versus benefit. Investment versus return. And sometimes, especially when times get tough, cheating becomes the better deal. This isn't just true for humans - it's a fundamental dynamic playing out across the natural world, from the microscopic bacteria in soil to the colorful fish patrolling coral reefs.

We've long celebrated nature's cooperators. The nitrogen-fixing bacteria that help legumes grow, the mycorrhizal fungi that extend plant root systems, the cleaner fish that remove parasites from larger species. These mutually beneficial partnerships seem like textbook examples of how cooperation evolves. But emerging research reveals a darker, more strategic reality: many of these supposed cooperators are actually conditional partners, ready to defect to selfish behavior the moment it becomes profitable.

This phenomenon - called mutualistic cheating - is reshaping how scientists understand cooperation itself. Rather than stable, harmonious relationships, symbioses are often tense negotiations where each partner is constantly monitoring whether they're getting a fair deal. And when conditions change, partners who were once helpful can become exploitative in a heartbeat.

At its core, mutualistic cheating is about economics. Cooperation requires investment - energy, nutrients, time - and that investment only makes sense when the return exceeds the cost. But what happens when the economics shift?

Consider the relationship between legume plants and rhizobia bacteria. The bacteria live in specialized root nodules, converting atmospheric nitrogen into forms the plant can use. In exchange, the plant provides the bacteria with carbohydrates from photosynthesis. It's a classic win-win.

Except when it isn't. Some rhizobia strains have lost the genes required for nitrogen fixation but still form nodules and extract carbohydrates from the plant. They're freeloaders, getting the benefits of the partnership without providing the service. From the bacterium's perspective, why invest energy in complex nitrogen-fixing machinery when you can get fed for free?

When soil nitrogen is abundant, cooperating bacteria waste resources fixing nitrogen that's already available. Cheaters that skip this expensive process can reproduce faster, fundamentally changing the economics of partnership.

The prevalence of these cheater strains varies dramatically with environmental conditions. When soil nitrogen is abundant, cooperating rhizobia waste resources fixing nitrogen that's already available. Cheaters that skip this expensive process can reproduce faster, spreading through the population. The partnership becomes a liability rather than an asset.

This dynamic isn't unique to bacteria. Mycorrhizal fungi, which form networks connecting plant roots and help them acquire phosphorus and other nutrients, engage in similar calculations. Research shows these fungi vary how much phosphorus they deliver based on how much carbon they receive from the plant. Some fungal strains extract carbon without providing proportional nutrient benefits - essentially charging inflated prices for their services.

The transition from cooperation to exploitation isn't always subtle. Under certain conditions, fungi previously in mutualistic relationships can turn fully parasitic, attacking weakened or stressed plants rather than helping them. The same organism that once enhanced the plant's growth becomes an active threat to its survival.

What triggers this flip from helper to parasite? Often it's environmental stress that changes the cost-benefit equation. A plant struggling with drought or disease becomes a less reliable partner - it has less surplus carbon to trade, making the mutualism less profitable for the fungus. At some threshold, the fungus gains more by abandoning cooperation and simply extracting resources by force.

This pattern appears across wildly different systems. Cleaner fish, which remove parasites and dead tissue from larger client fish, occasionally bite off pieces of healthy tissue and mucus instead. The behavior is essentially a cheat - taking a more nutritious meal while providing less cleaning service. Studies show this cheating increases when clients are less able to punish or abandon cheating cleaners, such as when the client fish is stressed or has limited cleaning options.

"Under certain conditions species of fungi previously in a state of mutualism can turn parasitic on weak or dying plants."

- Research on Mycorrhizal Dynamics, Wikipedia

The false cleanerfish takes this strategy even further. These species have evolved to mimic the appearance and behavior of legitimate cleaner fish, approaching client fish as if to clean them, then taking bites of tissue before swimming away. It's a pure exploitation strategy that only works because cooperative cleaner fish have established a system of trust.

If cheating is so advantageous, why doesn't it completely replace cooperation? The answer lies in partner control mechanisms - the ways organisms detect and respond to cheaters.

Legume plants have evolved surprisingly sophisticated quality control systems. They can monitor individual nodules to assess how much nitrogen fixation is occurring and respond by cutting off oxygen supply to underperforming nodules. This "sanctioning" system creates consequences for cheating bacteria, reducing their reproduction and giving cooperative strains a competitive advantage.

But sanctions aren't perfect. They require the host to invest energy in monitoring and enforcement. If the cost of policing exceeds the benefit of maintaining cooperation, hosts may tolerate low levels of cheating rather than pay the enforcement cost. This creates a stable equilibrium where some cheaters persist in the population.

The fig-wasp mutualism demonstrates another control mechanism. Female fig wasps pollinate fig flowers while laying their eggs inside the developing fruit. Some wasp species are "non-pollinators" that lay eggs without carrying pollen - classic cheaters. But fig trees have evolved to detect unpollinated flowers and selectively abort them, killing the cheating wasp's offspring. This punishment enforces cooperation by making cheating directly costly to the wasp's reproductive success.

Partner control mechanisms create an evolutionary arms race: cheaters evolve ways to avoid detection, while cooperators develop better monitoring systems. The result is a dynamic equilibrium where cooperation and cheating coexist.

These control mechanisms create an evolutionary arms race. Cheaters evolve ways to avoid detection or minimize sanctions. Cooperators evolve better detection and punishment systems. The result is a dynamic equilibrium where cooperation and cheating coexist, with the balance shifting based on environmental conditions and the effectiveness of control mechanisms.

Understanding cheating requires looking at the molecular level, where the actual negotiations occur. In the mycorrhizal symbiosis, plants and fungi exchange signals through complex chemical communication systems. Plants release compounds called strigolactones that attract fungal hyphae. Fungi respond with their own signals that suppress the plant's immune system, allowing the fungus to colonize root tissue.

This signaling system creates opportunities for manipulation. Some fungal strains have evolved to trigger stronger suppression of plant immune responses, allowing them to extract more resources while investing less in nutrient delivery. From the plant's perspective, it's like a contractor who sweet-talks you into paying upfront then delivers shoddy work.

Research on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi reveals just how precisely both partners track the exchange. Plants can adjust the amount of carbon they allocate to fungal partners based on the phosphorus they receive. Fungi, in turn, adjust their investment in phosphorus-gathering structures based on carbon supply. It's a constant calibration of trade terms.

When this calibration breaks down, the partnership destabilizes. If a fungus detects that the plant is unreliable or stingy with carbon, it may reduce its investment in costly phosphorus acquisition structures. The plant then receives even less phosphorus, potentially triggering it to cut back carbon allocation further. This downward spiral can convert a productive mutualism into a parasitic interaction where the fungus extracts carbon without providing proportional benefits.

The nitrogen-fixing symbiosis operates through similar molecular negotiations. Rhizobia bacteria use Nod factors to signal their presence and trigger nodule formation. Inside nodules, the bacteria differentiate into bacteroids - specialized forms that fix nitrogen but typically can't reproduce. This creates an opportunity for the plant to ensure cooperation: by controlling whether bacteria can reproduce before or after providing nitrogen fixation services, the plant aligns the bacteria's evolutionary interests with its own.

But this system isn't foolproof. Some rhizobia strains have evolved ways to reproduce inside nodules without fully differentiating, allowing them to maintain reproductive potential while potentially shirking nitrogen fixation duties. Others maintain functional nitrogen-fixing genes but downregulate them when environmental nitrogen is available, essentially going on strike when their services aren't uniquely valuable.

The stability of mutualistic partnerships is exquisitely sensitive to environmental conditions. Temperature, moisture, nutrient availability, and resource quality all influence whether cooperation or cheating is the better strategy.

Research on legume-rhizobia symbiosis shows that temperature stress can disrupt the partnership in multiple ways. High temperatures can reduce nitrogen fixation rates, making the bacteria less valuable to the plant. They can also increase the plant's respiration costs, leaving less surplus carbon to trade with bacteria. Either shift changes the cost-benefit calculation that maintains cooperation.

This sensitivity to environmental conditions has profound implications in our changing climate. As temperatures rise and precipitation patterns shift, the environmental contexts that stabilized historical mutualisms are changing rapidly. Partnerships that were reliably cooperative under previous conditions may tip toward exploitation under new environmental regimes.

"Mutualisms are not static, and can be lost by evolution through four main pathways: shift to parasitism, partner abandonment, partner extinction, or partner switching."

- Sachs and Simms (2006), on mutualism breakdown

Consider mycorrhizal associations in warming soils. Higher temperatures increase both plant and fungal metabolism, potentially creating carbon stress for plants while simultaneously reducing the efficiency of nutrient uptake processes. If plants have less carbon to trade while fungi need more energy to provide the same nutrient benefits, the partnership becomes less favorable for both parties. This could trigger increased cheating or even complete breakdown of the symbiosis.

The impacts extend beyond individual partnerships. Many ecosystems depend on cooperative mutualisms to function. Nitrogen fixation by legume-rhizobia partnerships contributes essential nitrogen to terrestrial ecosystems. Mycorrhizal networks help plants access phosphorus and facilitate nutrient exchange between plants. If climate change pushes these systems toward increased cheating or breakdown, ecosystem productivity and stability could decline.

Researchers are particularly concerned about threshold effects - points where environmental stress becomes severe enough to trigger rapid shifts from cooperation to exploitation. Unlike gradual degradation, threshold-driven collapses can be difficult to predict and reverse.

Understanding mutualistic cheating isn't just academic - it has immediate practical applications in how we manage beneficial organisms.

In agriculture, the challenge is ensuring that beneficial soil microbes actually provide their advertised services. When farmers inoculate legume seeds with rhizobia or add mycorrhizal fungi to soil, they're essentially introducing partners and hoping cooperation emerges. But if environmental conditions favor cheating, or if cheater strains are present, the inoculation may provide little benefit while still extracting resources from plants.

This has led to increased interest in screening microbial inoculants for reliability under varying conditions. Rather than assuming all rhizobia or mycorrhizal fungi will cooperate, researchers test strains across different temperatures, nutrient levels, and stress conditions to identify those that maintain cooperation even when cheating would be profitable. It's quality control for symbiotic partners.

Managing beneficial organisms requires creating conditions that make cooperation more profitable than exploitation - whether in agricultural soils, human microbiomes, or conservation efforts.

The same principles apply to managing plant microbiomes more broadly. Plants host complex communities of microorganisms, some beneficial, some harmful, many somewhere in between. Understanding what environmental conditions push microbes toward helpful versus exploitative behaviors could help farmers and gardeners create conditions that favor cooperation.

In medicine, the human microbiome presents similar challenges. We host trillions of bacteria, many of which provide benefits like synthesizing vitamins, training our immune system, and competing with pathogens. But microbial partners can also turn exploitative, potentially contributing to inflammatory diseases or metabolic disorders.

Recent research suggests that factors like diet, stress, and antibiotic use can shift the balance between cooperative and exploitative microbial behaviors. A bacterium that's normally beneficial might become problematic when the host's condition changes - essentially the same dynamic as fungi turning parasitic on stressed plants. This perspective suggests that managing the microbiome requires not just adding beneficial bacteria, but creating conditions that maintain cooperative relationships.

The challenge extends to efforts at engineering synthetic mutualisms - deliberately creating new cooperative partnerships for applications like biomanufacturing or environmental remediation. Creating initial cooperation is relatively straightforward through genetic engineering. But maintaining cooperation over evolutionary time, especially under varying environmental conditions, requires addressing the same economic incentives that drive cheating in natural systems.

The discovery of widespread mutualistic cheating fundamentally changes how we think about cooperation in nature. The traditional view portrayed mutualisms as stable, harmonious partnerships that evolved because they benefit both parties. The reality is more strategic and context-dependent.

Cooperation emerges not from harmony but from aligned incentives. When the benefits of cooperating exceed the costs, and when partners have effective ways to detect and punish cheating, cooperation can be stable. But this stability is conditional - change the environmental context or the effectiveness of control mechanisms, and cheating can quickly become the better strategy.

This perspective connects to broader questions in evolutionary biology about the origins and maintenance of cooperation. Whether we're talking about bacteria, plants, fish, or humans, cooperation faces the same fundamental challenge: defectors can reap the benefits of others' cooperation without paying the costs. Any cooperative system that can't address this free-rider problem will be vulnerable to exploitation and eventual collapse.

The various solutions that have evolved - sanctions, partner choice, reputation effects, genetic relatedness - all serve to align individual incentives with collective benefit. They change the payoff structure so that cooperation becomes individually profitable, not just collectively beneficial.

But these solutions are never perfect, and they're always contingent on environmental conditions. A sanctioning system that effectively maintains cooperation under one set of conditions may fail under others. A reputation system that works when partners interact repeatedly may break down when interactions are fleeting. The strategic calculation is constantly running, always context-dependent.

Climate change, habitat fragmentation, pollution, and other human-caused environmental changes are altering the conditions that shaped historical mutualisms. We're essentially running a massive, uncontrolled experiment on whether these partnerships will remain stable or tip toward exploitation.

Some ecosystems may prove resilient, with partnerships adapting to new conditions while maintaining cooperation. Others may experience mutualism breakdown, with cascading effects on ecosystem function. Predicting which systems will thrive and which will collapse requires understanding the specific environmental thresholds and control mechanisms that maintain each partnership.

There's also the possibility of evolutionary rescue - populations adapting fast enough to maintain cooperation under new conditions. This could involve hosts evolving better monitoring and sanctioning abilities, or symbionts evolving to remain cooperative under a broader range of conditions. But evolutionary adaptation requires genetic variation and time, both of which may be in short supply for rapidly changing environments.

The research on mutualistic cheating also opens new questions about cooperation in human societies. We like to think our cooperation is fundamentally different from the conditional exchanges of bacteria and plants. But many of the same dynamics apply - the challenge of detecting cheaters, the cost of enforcement, the way environmental stress can push individuals toward selfish behavior.

"The same mathematical frameworks used to analyze human cooperation - prisoner's dilemmas, tragedy of the commons - apply remarkably well to interactions between organisms that don't think at all."

- Recent theoretical work on evolutionary game theory

Understanding cooperation as conditional exchange, always subject to strategic calculation based on costs and benefits, might help us build more robust cooperative systems. Rather than assuming cooperation will naturally persist because it's mutually beneficial, we can actively design institutions and incentives that make cooperation remain individually profitable even when conditions change.

Perhaps the most profound insight from this research is how strategic all of life is. Even organisms without nervous systems are constantly running evolutionary cost-benefit analyses. Bacteria are tracking nutrient flows and adjusting gene expression to maximize reproductive success. Plants are monitoring partner quality and allocating resources accordingly. Fungi are calibrating their investment in nutrient acquisition based on carbon availability.

This isn't conscious strategy, of course. It's the result of billions of years of natural selection favoring organisms that respond adaptively to their circumstances. But the result is sophisticated systems of negotiation, monitoring, and enforcement that rival anything humans have invented.

We see this reflected in recent theoretical work applying game theory to mutualistic interactions. The same mathematical frameworks used to analyze human cooperation - prisoner's dilemmas, tragedy of the commons, tit-for-tat strategies - apply remarkably well to interactions between organisms that don't think at all.

This universality suggests that cooperation and cheating aren't specific to particular types of organisms. They're fundamental features of any system where individuals can gain from interaction but also face temptations to cheat. The specific mechanisms vary - plants use oxygen deprivation to sanction cheating bacteria, humans use laws and social norms - but the underlying strategic structure is the same.

As we continue to modify global environments and attempt to manage beneficial organisms for human purposes, understanding these strategic dynamics becomes crucial. We can't simply assume that mutually beneficial partnerships will persist because they're good for both parties. We need to understand the specific conditions that maintain cooperation and actively work to preserve those conditions.

The partnership between humans and the natural world might be the most important mutualism of all. And like all mutualisms, it's vulnerable to exploitation when one party extracts benefits without providing proportional returns. Understanding what maintains cooperation in other symbioses might help us understand what's needed to maintain our own partnership with the living systems that sustain us.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

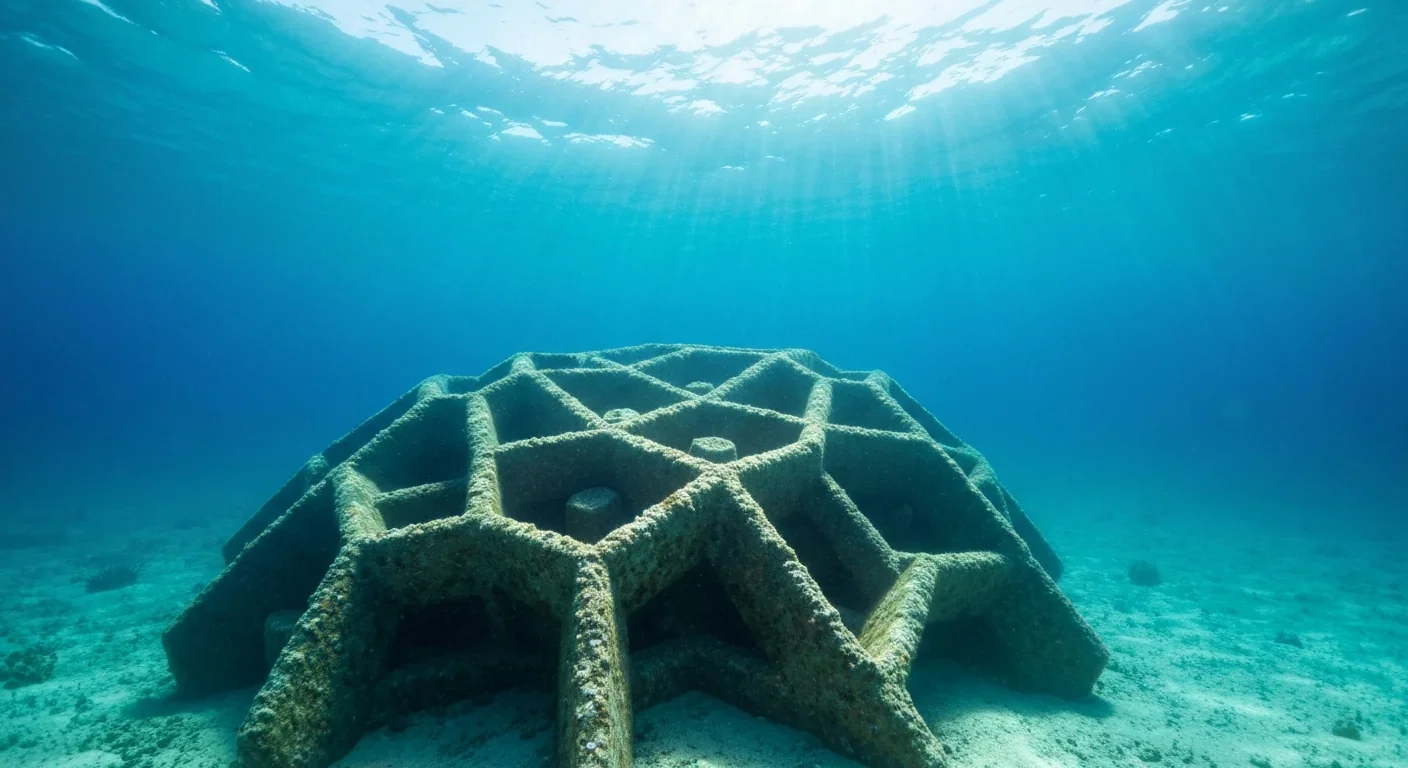

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

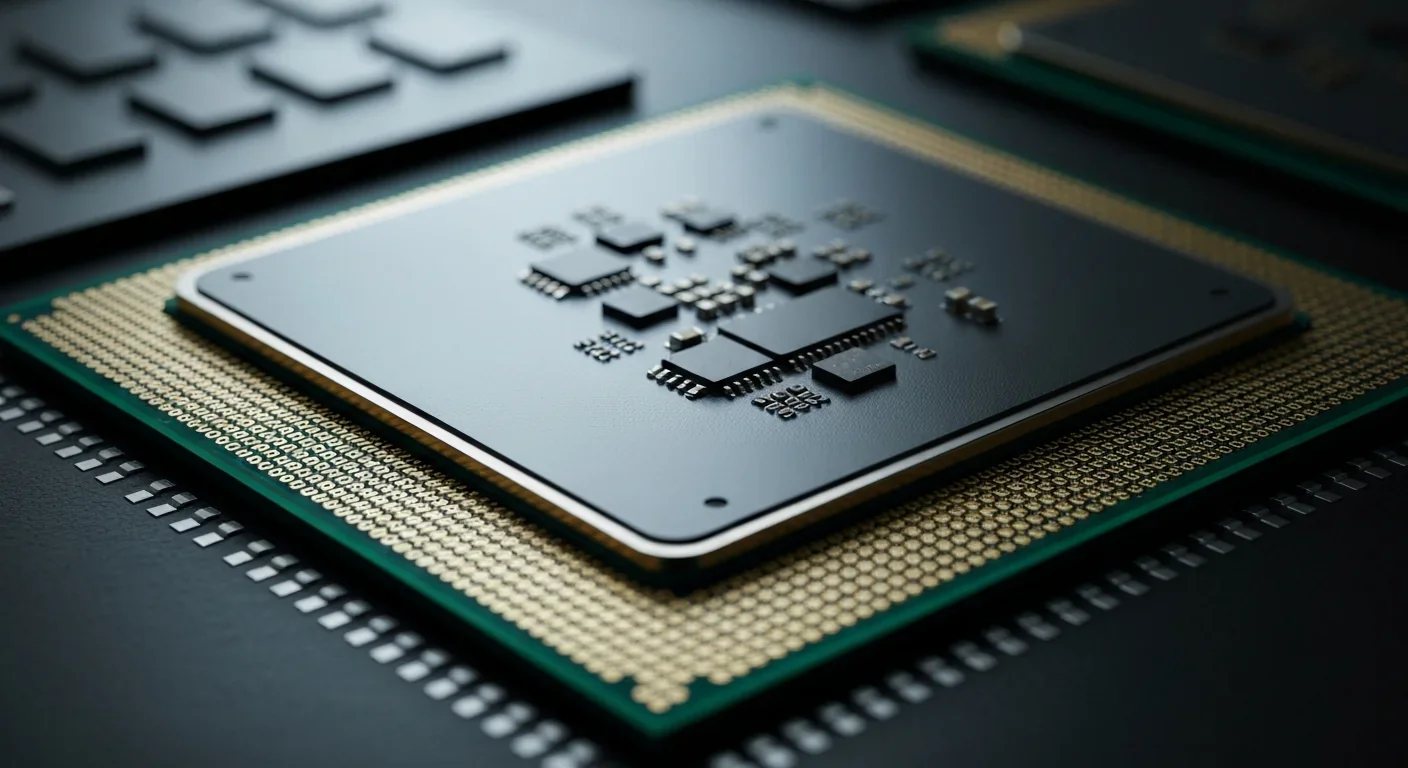

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.