Nature's First Farmers: 50 Million Years of Ant Agriculture

TL;DR: Rough-skinned newts in the Pacific Northwest produce lethal amounts of tetrodotoxin, while garter snakes have evolved molecular resistance through sodium channel mutations. This predator-prey arms race demonstrates natural selection in real time, with geographic variation showing different escalation levels and both species paying metabolic costs for their extreme adaptations.

In the forests of the Pacific Northwest, an invisible war has raged for thousands of years. The rough-skinned newt (Taricha granulosa) produces one of nature's deadliest toxins in concentrations that could kill dozens of humans. Meanwhile, certain garter snakes have evolved such extreme resistance that they can devour these poisonous amphibians without flinching. This isn't science fiction - it's one of the most dramatic examples of evolutionary escalation ever documented, where predator and prey continuously one-up each other in a biochemical battle that reshapes both species.

Rough-skinned newts pack tetrodotoxin (TTX), the same nerve poison found in pufferfish. But while pufferfish are famous for their lethality, some newt populations have taken toxicity to horrifying extremes. A single rough-skinned newt from northern Oregon can contain enough TTX to kill 25,000 mice - or more than 20 adult humans.

TTX works by blocking voltage-gated sodium channels in nerve and muscle cells. These channels are essential for transmitting electrical signals throughout the body. When TTX molecules bind to these channels, they prevent sodium ions from entering cells, effectively shutting down the nervous system. Within minutes, victims experience numbness, paralysis of voluntary muscles, and ultimately respiratory failure when the diaphragm stops functioning.

A single rough-skinned newt from northern Oregon contains enough tetrodotoxin to kill 25,000 mice or more than 20 adult humans. There is no antidote.

The toxin doesn't just kill - it does so with terrifying efficiency. There's no antidote. Medical treatment consists of life support until the toxin degrades naturally, which can take hours or days. For most animals that bite into a rough-skinned newt, there is no second chance.

Here's where evolution gets interesting. The common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis) regularly eats these toxic newts in certain regions - and survives.

This shouldn't be possible. The same sodium channels that TTX targets exist in virtually all animals, from fish to humans. They're so fundamental to nervous system function that evolution rarely modifies them significantly. Yet garter snakes in areas with toxic newts have evolved specific amino acid substitutions in their sodium channel proteins that prevent TTX from binding effectively.

Scientists discovered that resistance centers on the Nav1.4 sodium channel, particularly in the skeletal muscle. Specific mutations in the extracellular loops of these channels - particularly at positions where TTX normally binds - create resistance. Some snake populations carry multiple resistance mutations, creating different levels of protection against the toxin.

But this resistance comes at a cost. The mutations that prevent TTX binding also affect normal sodium channel function. Highly resistant snakes move more slowly than their non-resistant counterparts because their modified channels don't transmit nerve signals as efficiently. It's a metabolic trade-off: gain resistance to the toxin, lose some athletic performance.

The coevolution between newts and snakes isn't uniform across their range - it forms what biologists call a "geographic mosaic." In some locations, the evolutionary arms race has escalated to extreme levels. In others, it barely exists.

Northern Oregon represents a coevolutionary hotspot. Here, rough-skinned newts reach their highest toxicity levels, and local garter snakes show the most extreme resistance. A snake in this region might carry four or five resistance mutations and can consume newts that would instantly kill snakes from other populations.

Travel to Vancouver Island in British Columbia, and the picture changes dramatically. The rough-skinned newts there produce little or no TTX. Correspondingly, local garter snakes lack resistance mutations. It's a coevolutionary coldspot where the arms race never got started - or perhaps where it cooled down after reaching unsustainable levels.

"In coevolutionary hotspots, both toxicity and resistance escalate to extreme levels. In coldspots, the arms race barely exists. This geographic mosaic provides a natural laboratory for studying evolution in action."

- Edmund Brodie III, University of Virginia

California and Washington populations fall somewhere in between, with moderate toxicity in newts and intermediate resistance in snakes. This geographic variation provides scientists with a natural laboratory for studying how coevolution proceeds at different intensities.

Understanding this arms race requires diving into the molecular details. Tetrodotoxin is a small molecule with a unique structure that fits precisely into the outer pore of voltage-gated sodium channels. Think of it as a molecular cork that plugs a critical bottleneck.

In TTX-sensitive organisms, the toxin binds with extraordinary affinity - dissociation constants in the nanomolar range. This means incredibly tiny amounts can block channels effectively. The binding site involves specific amino acids that form a kind of molecular pocket where TTX nestles in.

Resistant snakes have altered this pocket through point mutations. The most important changes occur at positions 1561, 1564, and 1568 in the Nav1.4 channel (using standard numbering). By substituting different amino acids at these positions, snakes change the shape of the TTX binding site just enough that the toxin can't fit as tightly.

But evolution can't simply delete the sodium channel or radically redesign it. These channels are too essential. So natural selection works within tight constraints, making the smallest possible changes that confer resistance while maintaining basic channel function. It's biochemical improvisation under severe limitations.

This newt-snake system perfectly illustrates the Red Queen hypothesis, named after the character in "Through the Looking-Glass" who tells Alice, "It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place." In evolutionary terms, species must constantly adapt just to maintain their current fitness as their competitors also evolve.

Edmund Brodie Jr., Edmund Brodie III, and their colleagues have studied this system for decades, creating one of the most detailed portraits of predator-prey coevolution in the wild. Their research shows that neither species can rest on its evolutionary laurels. When newts evolve higher toxicity, natural selection favors snakes with greater resistance. When snakes evolve better resistance, selection favors newts that produce even more toxin.

The result is an evolutionary treadmill where both species keep running but neither gains permanent advantage. Over thousands of generations, toxicity and resistance have escalated to levels far beyond what would be needed to deter or consume ordinary predators and prey.

Evolution rarely gives something for nothing, and the newt-snake arms race demonstrates this principle clearly. Both species pay substantial costs for their extreme adaptations.

For newts, producing massive amounts of TTX is metabolically expensive. The toxin doesn't benefit the individual newt that gets eaten - it's a population-level defense. Highly toxic newts may allocate resources to poison production that could otherwise go to growth, reproduction, or immune function. Recent research shows that TTX levels vary within populations and even within individuals over time, suggesting trade-offs with other biological processes.

Resistant snakes face their own costs. The mutations that provide TTX resistance reduce the efficiency of sodium channels during normal function. This manifests as slower movement speeds and reduced sprint performance. In areas without toxic newts, resistant snakes would be at a competitive disadvantage compared to non-resistant individuals.

Resistant snakes pay a steep price for their adaptation: their modified sodium channels reduce movement speed and sprint performance compared to non-resistant snakes.

These costs help explain the geographic mosaic pattern. In areas where newts and snakes frequently interact and predation pressure is high, the benefits of toxicity and resistance outweigh the costs. In areas where they rarely encounter each other, maintaining extreme adaptations makes no evolutionary sense.

Documenting this coevolutionary process requires creative research methods. Scientists can't observe speciation in real time or run thousand-generation experiments with vertebrates. Instead, they've assembled evidence from multiple approaches.

Phenotypic studies measure toxicity and resistance levels across different populations. Researchers collect newts from various locations and use mass spectrometry to quantify TTX concentrations. For snakes, they inject measured doses of TTX and observe whether snakes can survive and function normally - a test that reveals the degree of resistance.

Genetic analyses identify the specific mutations associated with resistance. By sequencing sodium channel genes from snakes across the geographic range, researchers can track which populations carry resistance alleles and how many mutations they possess.

Phylogenetic studies reveal the evolutionary history of these adaptations. By comparing sodium channel sequences across snake species, scientists can determine when resistance mutations first appeared and how many times they've evolved independently. Remarkably, TTX resistance has evolved multiple times in different snake lineages that feed on toxic prey.

Ecological experiments test the fitness consequences of these traits. Researchers compare the speed and endurance of resistant versus non-resistant snakes, measure predation rates in different regions, and assess how often snakes actually consume newts in the wild.

While the rough-skinned newt and garter snake system is among the best-studied, it's not unique. TTX resistance has evolved independently in several other animals that encounter this toxin. Pufferfish themselves are resistant to their own poison, as are some species of crabs, octopuses, and other predators of toxic prey.

Even more broadly, the pattern of coevolutionary arms races appears throughout nature. Parasites and hosts continually evolve new attacks and defenses. Plants produce toxins; herbivores evolve detoxification mechanisms. Bats echolocate; moths evolve ears to hear them and take evasive action.

The newt-snake system provides exceptional insight into these processes because it involves measurable, genetically tractable traits in well-studied organisms that live in accessible habitats. It's a model system where theories about coevolution can be tested with real data.

Can this arms race escalate indefinitely? Probably not. Both species face constraints that limit how far evolution can push them.

For newts, there are upper limits to how much TTX they can produce and store safely. The toxin must be sequestered in ways that don't harm the newt itself, requiring specialized cellular machinery. At some point, producing more toxin yields diminishing returns.

For snakes, the constraints are even more obvious. Sodium channels can only be modified so much before they stop functioning altogether. There may be only a limited number of amino acid substitutions that reduce TTX binding without completely destroying channel function. Snakes might be approaching the ceiling of possible resistance.

Some populations may have already hit these limits. The most toxic newts and most resistant snakes might represent the maximum possible values for their traits. If so, the arms race in those hotspot regions may have reached an uneasy stalemate.

Alternatively, entirely new mutations could emerge that overcome current limitations. Evolution is creative, and there may be resistance mechanisms that haven't yet appeared. The future trajectory of this coevolutionary relationship remains uncertain.

The rough-skinned newt and garter snake arms race illuminates several key principles about how evolution works in nature.

First, it demonstrates that evolution is ongoing, not something that only happened in the distant past. Natural selection is actively shaping these populations right now. The geographic variation in toxicity and resistance represents evolution in action across different environments.

Second, it shows that adaptation has costs. Evolution doesn't produce perfect organisms - it produces organisms that are good enough to survive and reproduce in their specific environment. The trade-offs between resistance and performance in snakes illustrate this clearly.

Third, it reveals how interactions between species can drive evolutionary change. The traits of newts and snakes make sense only in relation to each other. Neither species would have evolved such extreme characteristics in isolation.

"This system shows us that evolution doesn't create perfection - it creates trade-offs. The same mutations that save a snake from poisoning also slow it down. That's natural selection working within real-world constraints."

- Dr. Chris Feldman, University of Nevada, Reno

Fourth, it highlights the importance of molecular and genetic mechanisms. Understanding this arms race requires knowing exactly which genes are involved, what mutations occurred, and how those mutations alter protein function. Evolution happens at the molecular level, and biochemical details matter.

This might seem like an obscure natural history story with little relevance to human concerns. But understanding coevolution has practical applications.

TTX and related toxins are being investigated as potential painkillers. Because they block sodium channels, they can prevent pain signals from traveling through nerves. Researchers are exploring modified versions with more selective effects that could treat chronic pain without the deadly side effects of the natural compound.

The sodium channels that TTX targets are also involved in various medical conditions. Mutations in human sodium channel genes cause cardiac arrhythmias, epilepsy, and periodic paralysis. Understanding how garter snake mutations alter channel function provides insights that could help design better treatments for these conditions.

More broadly, studying coevolutionary arms races informs our understanding of antibiotic resistance, pest management, and conservation biology. The same evolutionary dynamics that drive newts and snakes toward extreme adaptations also govern how bacteria evolve resistance to drugs and how crop pests adapt to pesticides.

The rough-skinned newt and garter snake continue their deadly dance in the forests and wetlands of the Pacific Northwest. Every generation, natural selection sorts through variations in toxicity and resistance, favoring individuals whose traits give them a slight edge.

Scientists continue to study this remarkable system, publishing new findings about the molecular mechanisms involved, the ecological contexts that promote escalation, and the evolutionary history that produced today's patterns. Each study adds detail to our understanding of how coevolution proceeds.

This arms race reminds us that nature is not static. Evolution is an ongoing process driven by interactions between organisms. The adaptations we see today are temporary solutions to current problems, and they'll be modified by future evolutionary pressures we can't predict.

In the end, neither newts nor snakes "win" this arms race. Both species are shaped by their relationship with each other, locked in an evolutionary embrace that has produced some of nature's most extreme toxins and resistance mechanisms. It's a story of escalation, constraint, and the endless creativity of natural selection - all playing out in small amphibians and snakes that most people never notice.

Yet these unassuming creatures have much to teach us about how life evolves, adapts, and responds to challenges. The next time you see a rough-skinned newt in a stream or a garter snake basking on a trail, remember: you're witnessing participants in one of evolution's most dangerous experiments, a biological arms race that has no finish line.

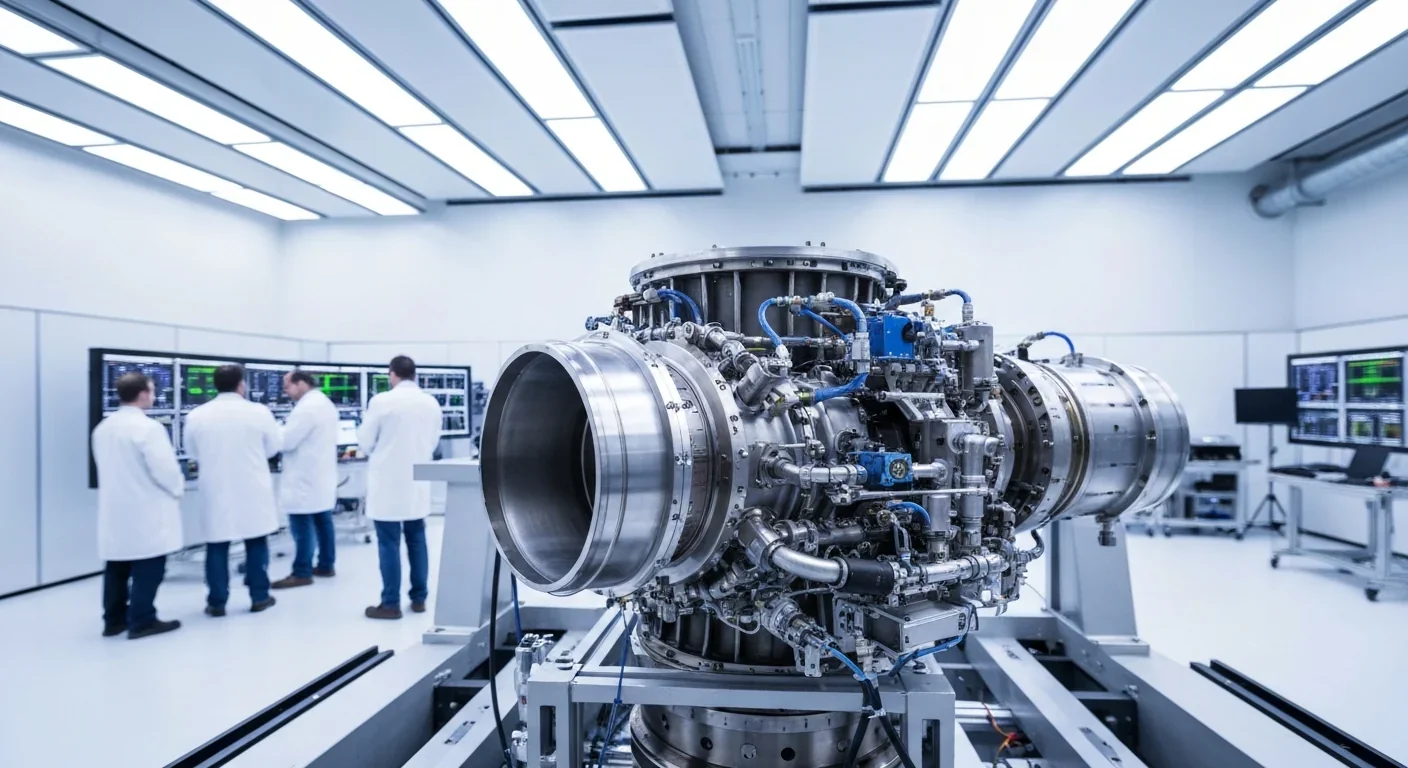

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

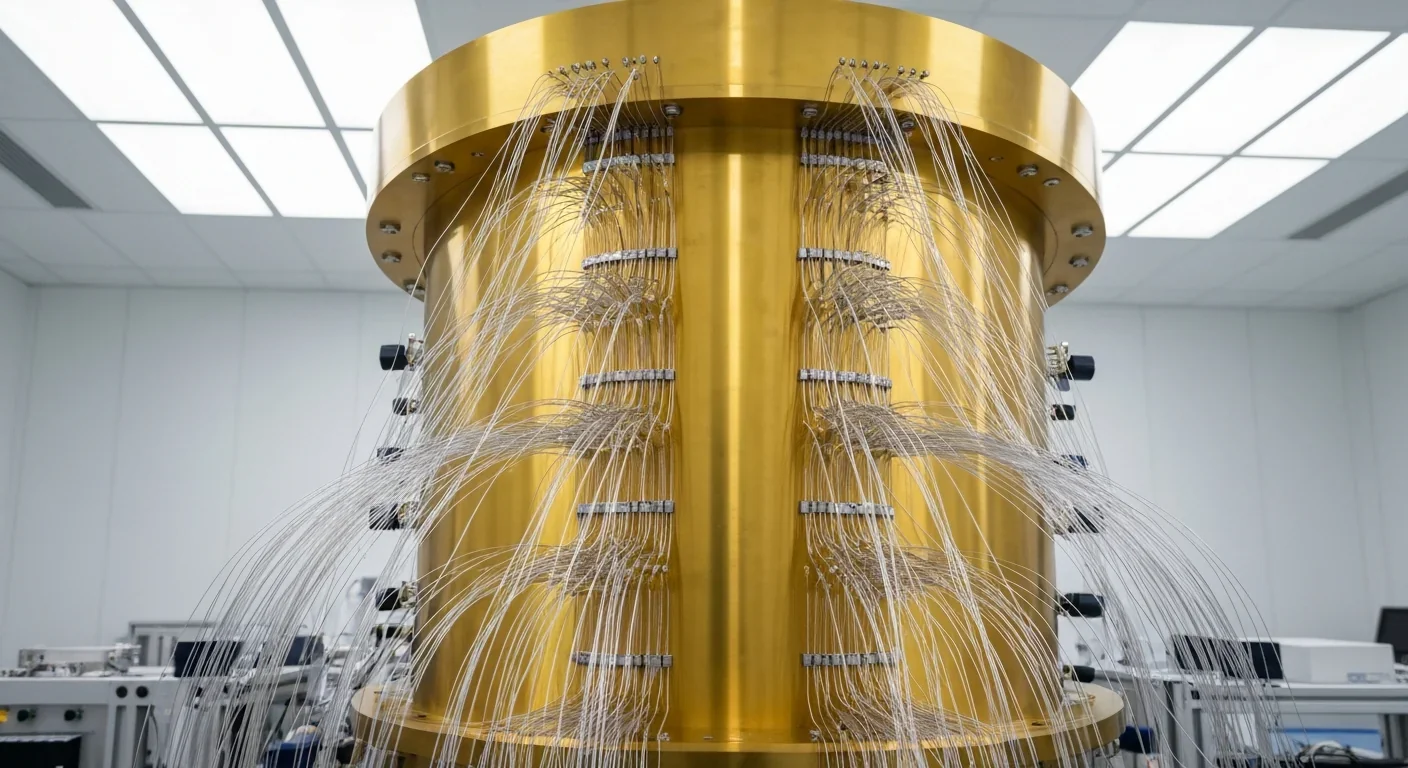

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.