Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Termites mastered sustainable agriculture 30 million years ago, cultivating specialized fungi in complex underground farms. Their techniques - precision pest control, circular resource use, and passive climate systems - offer crucial lessons for modern farming's sustainability challenges.

Long before humans planted their first seeds, tiny farmers were already perfecting sustainable agriculture. Not in some ancient human civilization, but deep underground in the intricate colonies of fungus-growing termites. These remarkable insects didn't just stumble upon farming - they evolved a sophisticated agricultural system roughly 30 million years ago that puts many modern practices to shame.

The story of termite agriculture challenges everything we thought we knew about farming. It forces us to reconsider what intelligence really means and whether humanity's greatest achievements are truly unique. More importantly, these miniature farmers might hold secrets that could help us build more sustainable food systems for our own future.

In the African savannas, Asian forests, and tropical regions across the Old World, members of the termite subfamily Macrotermitinae have been practicing agriculture since the Oligocene epoch. Their crop? A specialized fungus called Termitomyces - the only genus of fungi that exists exclusively through cultivation.

What makes this partnership extraordinary isn't just its age. It's the complete mutual dependence that has evolved between farmer and crop. The termites cannot digest the plant material they collect without the fungus breaking it down first. Meanwhile, Termitomyces has become so specialized that it can't survive without constant termite tending. Evolution has locked them together in an embrace neither can escape.

Termites discovered agriculture 30 million years ago through convergent evolution - proving that farming isn't a uniquely human innovation, but a natural strategy that emerges when conditions align.

This is convergent evolution at its most striking. Just as leaf-cutter ants independently evolved fungus farming in the Americas around the same time, termites discovered agriculture on their own. The fact that these distantly related insects arrived at nearly identical solutions suggests that farming isn't some miraculous human invention - it's a strategy that emerges naturally when certain conditions align.

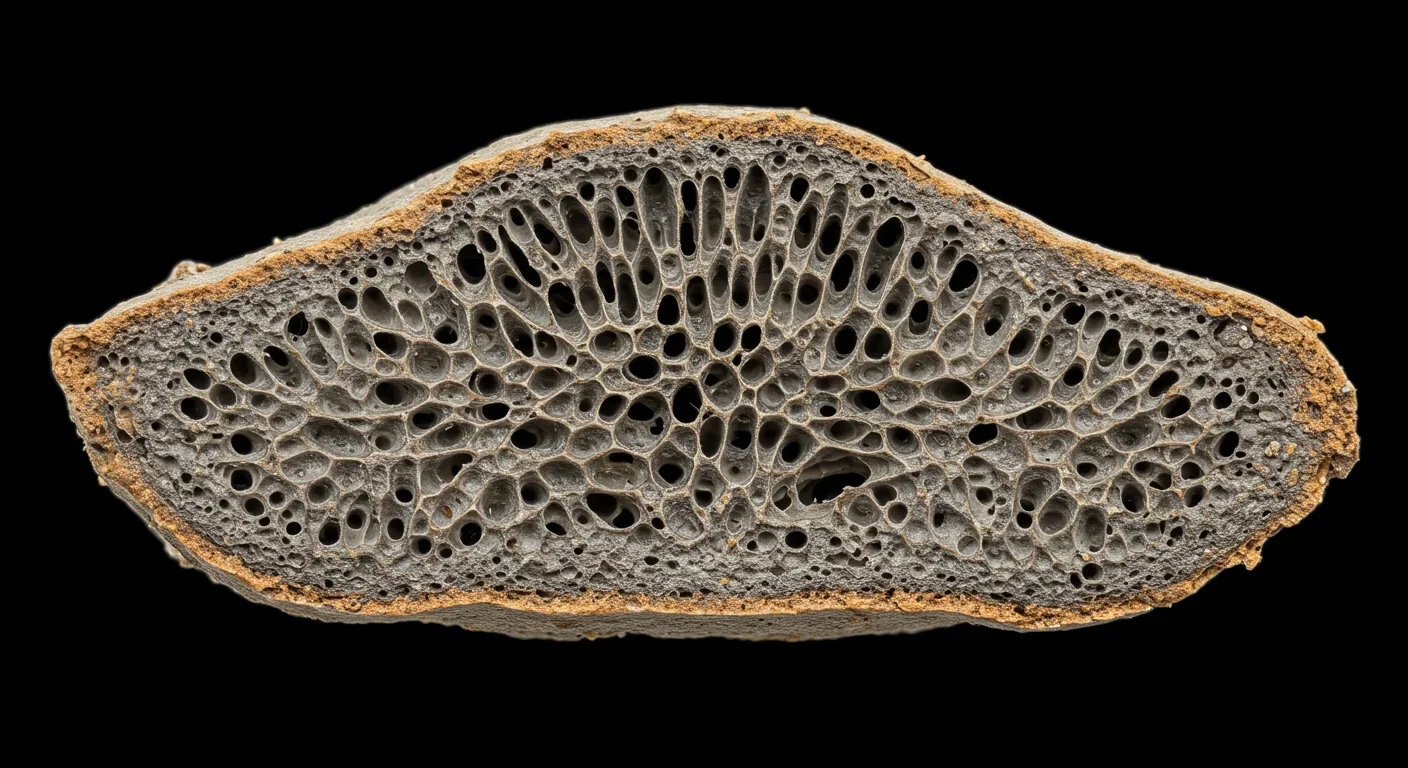

Walk into a termite mound and you'll find something that looks remarkably like a farm. The heart of the colony is the fungal garden - spongy, gray-brown structures called combs that fill chamber after chamber. These aren't random growths. They're carefully constructed agricultural installations.

The farming process starts with foraging. Worker termites venture out to collect dead plant material - wood, leaves, grass, anything cellulose-rich. But they don't bring it straight to the fungus. Instead, they eat it, mixing it with fungal spores in their guts for about 3.5 hours. What comes out the other end is perfectly prepared substrate, inoculated and ready for cultivation.

This isn't primitive behavior. The termites are essentially creating a living compost system, one that agricultural scientists are only now beginning to appreciate. Each worker deposits its processed material in layers, building the comb structure that will support fungal growth. Within about two weeks, small white nodules appear - concentrated packets of fungal tissue that represent the actual "crop."

The sophistication doesn't end there. Termites maintain their gardens with practices any human farmer would recognize: weeding, temperature control, humidity management, and harvest timing. They constantly monitor conditions, adjusting ventilation and making repairs to keep their fungus thriving in an environment that stays remarkably stable despite external weather variations.

Recent research has uncovered even more impressive agricultural techniques. A 2025 study found that termites actively manage competing fungi through chemical warfare, selectively removing contaminating species while promoting Termitomyces growth. They're not just passive cultivators - they're active ecosystem managers practicing precision agriculture on a microscopic scale.

Termitomyces is unlike any other fungal genus. While most mushrooms grow freely in soil and wood, every single one of the roughly 40 species in this genus exists only within termite colonies. Scientists have never found wild populations. The fungus has become completely domesticated, evolutionarily speaking.

This represents one of nature's most complete examples of agricultural domestication. Just as corn can no longer disperse its seeds without human intervention, Termitomyces requires termite cultivation to complete its life cycle. The fungus produces massive mushrooms - some species like Termitomyces schimperi can reach 40 centimeters in diameter - but these fruiting bodies serve primarily to spread spores to new colonies, not to establish independent growth.

"The termites are unable to digest most of the plant matter they consume and get little nourishment from it, so they depend for survival on the fungi, which, in turn, cannot grow except when tended by termites."

- Journal of Economic Entomology

The relationship runs deep at the molecular level. The fungus produces specialized enzymes called cellulases that break down the tough plant material termites collect. Without these enzymes, the termites would starve despite having mouths full of vegetation. In return, the termites provide the fungus with pre-processed substrate, perfect growing conditions, and protection from competitors and pathogens.

What's remarkable is how the partnership has shaped both organisms' biology. Termites have lost much of their own digestive capability, outsourcing the work to their fungal partners. The fungus, meanwhile, has optimized for rapid growth in the specific conditions termites provide - high humidity, stable temperature, and constant care. They've co-evolved into a single, distributed organism that spans both kingdoms of life.

Different termite species cultivate different Termitomyces varieties, and researchers have found that the genetic relationships between fungal strains mirror those between their termite hosts. This parallel evolution suggests millions of years of tight partnership, with termite lineages passing down their domesticated fungi through vertical transmission - much like human farmers saving seeds from one season to the next.

The similarities between termite agriculture and human farming are unsettling in their precision. Both systems involve collecting plant material, processing it, creating optimal growing conditions, managing competing species, and timing the harvest. Both have led to complete domestication of the crop species. Both sustain massive population densities that would be impossible without agriculture.

But the differences reveal just how much termites got right. Human agriculture emerged only about 12,000 years ago - termites have had 30 million years to perfect their techniques. And in many ways, their approach appears more sustainable than ours.

Consider monoculture, one of modern agriculture's biggest problems. We know that planting single crops across vast areas invites diseases and pests, requiring heavy pesticide use. Termites also practice monoculture - each colony cultivates just one Termitomyces strain. Yet they maintain these gardens for decades without the catastrophic disease outbreaks that plague human crops.

How? Through integrated pest management that makes our best practices look crude. Termites incorporate antimicrobial compounds into their combs - recent studies identified molecules like dicrotalic acid that suppress a broad spectrum of bacteria, including drug-resistant strains. They maintain multiple defense layers: physical barriers, chemical weapons, constant surveillance, and behavioral responses to contamination.

The fungal gardens themselves create a highly selective microenvironment. The specific combination of humidity, temperature, pH, and chemical composition favors Termitomyces while inhibiting competitors. It's precision agriculture at a scale and sophistication that human farmers are only beginning to approach with modern sensors and data analytics.

Termite colonies maintain sustainable monocultures for decades without disease outbreaks by incorporating antimicrobial compounds, maintaining multiple defense layers, and creating highly selective growing environments.

Then there's sustainability. Termite agriculture operates in perfect circular loops. Nothing is wasted. The termites eat the fungal nodules, producing workers and soldiers to maintain the colony. The fungus digests plant material that would otherwise decompose slowly, accelerating nutrient cycling in ecosystems. Even the massive mounds - some reaching 30 feet tall - serve multiple functions: climate control, defense, and vertical farming architecture that maximizes space.

Human agriculture, by contrast, often depletes soil, requires massive external inputs of water and nutrients, and generates significant waste. We're still learning the lessons termites mastered millions of years ago: work with natural systems, close nutrient loops, and build resilience through careful management rather than brute force.

One of the biggest questions about termite agriculture is how it started. Agriculture isn't an obvious survival strategy - it requires upfront investment, specialized knowledge, and coordinated social behavior. So how did mindless evolution stumble upon something that took humans thousands of years of cultural development to achieve?

The answer lies in incremental steps, each providing immediate benefits. The ancestors of modern fungus-growing termites probably began by simply living in decomposing wood where fungi naturally grew. Some termites may have gained slight advantages by encouraging fungal growth - perhaps by keeping the wood moist or removing competing microbes.

Over time, natural selection favored termites that were better at promoting beneficial fungi. Termites that could concentrate fungal growth, protect it from competitors, and harvest it efficiently produced more offspring. Meanwhile, fungi that grew better under termite management spread more successfully. The partnership intensified through positive feedback loops spanning millions of generations.

The transition to obligate agriculture - where neither partner can survive without the other - probably happened gradually. As termites became more specialized farmers, they lost the ability to digest plant material independently. As Termitomyces adapted to termite cultivation, it lost the ability to grow freely in nature. By the time the partnership became obligate, both organisms were locked in, committed to agriculture for evolutionary perpetuity.

"The relationship between termites and fungi is a matter of life and death."

- Ed Ricciuti, Entomology Today

This evolutionary trajectory offers profound insights into human agricultural origins. We didn't invent farming from scratch any more than termites did. Like them, we probably started with small-scale management of wild plants, gradually intensifying the relationship until both we and our crops became dependent on each other. Wheat can barely reproduce without human help now. Corn would go extinct in a generation if we stopped planting it. We've followed the same evolutionary path as the termites, just much more recently.

Recent breakthroughs have revealed that termite farmers use chemical strategies we're only now discovering. When scientists analyzed fungal comb extracts from Senegalese termite colonies, they found powerful antimicrobial compounds that inhibit a wide range of bacteria - including modern drug-resistant strains.

The most abundant compound, dicrotalic acid, comes from the plants termites collect. This means termites may selectively forage for vegetation rich in antimicrobial chemicals, essentially practicing pharmaceutical agriculture alongside food production. They're not just growing food - they're creating a medicated environment that keeps their crops healthy.

The implications are staggering. Human agriculture struggles with disease management, relying heavily on synthetic pesticides and antibiotics. Termites have achieved the same goal through careful selection of inputs and environmental management. They're showing us that sustainable disease control is possible in intensive monoculture - you just need to think in terms of ecosystem engineering rather than chemical warfare.

This has practical applications. Researchers are now exploring whether compounds from termite gardens could provide new antibiotics or agricultural biocontrol agents. At a time when antibiotic resistance threatens modern medicine and pesticide resistance challenges food security, ancient termite farmers might offer solutions.

There's an ironic twist to this story. The same termites whose agriculture fascinates scientists also cause billions of dollars in damage to human crops and structures. Fungus-growing termites in Asia and Africa destroy sugarcane, maize, groundnuts, and eucalyptus plantations.

What makes them particularly challenging pests is precisely what makes them fascinating farmers. Their sophisticated chemical defenses interfere with control methods. Termitomyces produces enzymes that detoxify chitin synthesis inhibitors, the most common chemical weapon humans use against termites. The larger and more established the fungal garden, the more resistant the colony becomes to our control attempts.

This creates a peculiar situation where we're essentially in an agricultural arms race with insects. They've had 30 million years to refine their techniques. We've had barely a century with modern pesticides. It's not clear who has the advantage.

But this conflict also reveals how much we still have to learn. Termites show us that sustainable, resilient agriculture is possible - we're just approaching the problem from the wrong angle. Instead of trying to eliminate them, perhaps we should study their methods more carefully and adapt them to human-scale farming.

As climate change threatens conventional agriculture and global population continues rising, termite farmers offer a masterclass in sustainable food production. Their success rests on principles we're only beginning to embrace: circular resource use, biological pest control, precision environmental management, and deep integration with natural cycles.

Consider their architecture. Termite mounds are marvels of passive climate control, maintaining stable internal temperatures using carefully designed ventilation systems that require no energy input beyond the termites' own maintenance work. Engineers are now studying these structures to design more efficient buildings that use similar principles.

Termite mounds demonstrate perfect passive climate control - engineers are now studying these structures to design energy-efficient buildings that mimic nature's 30-million-year-old design.

Or take their waste management. In termite agriculture, there is no waste. Every byproduct feeds back into the system. Old comb layers are consumed, recycling nutrients. Fungal spores spread to maintain the culture. Dead termites contribute organic matter. The system is perfectly circular, something human agriculture rarely achieves.

Perhaps most importantly, termites demonstrate that intensive farming and ecological health aren't necessarily opposed. Their colonies are among the most important ecosystem engineers in tropical and subtropical regions, accelerating decomposition and nutrient cycling across vast areas. Human agriculture could learn from this integration rather than treating farming as something separate from natural ecosystems.

The existence of termite agriculture forces uncomfortable questions about human uniqueness. We like to think farming proves our intelligence and cultural sophistication. But termites achieve similar results through evolution alone, without brains capable of thought as we understand it.

This doesn't diminish human achievement - our agriculture is vastly more diverse and flexible than termite farming. But it does suggest that behaviors we consider markers of intelligence can emerge through non-cognitive pathways. The same might be true of other supposedly unique human traits.

There's something humbling about realizing that tiny insects with neural systems orders of magnitude simpler than ours independently discovered one of our species' foundational innovations. It reminds us that evolution is a powerful problem-solver, capable of finding solutions we consider clever through blind trial and error given enough time.

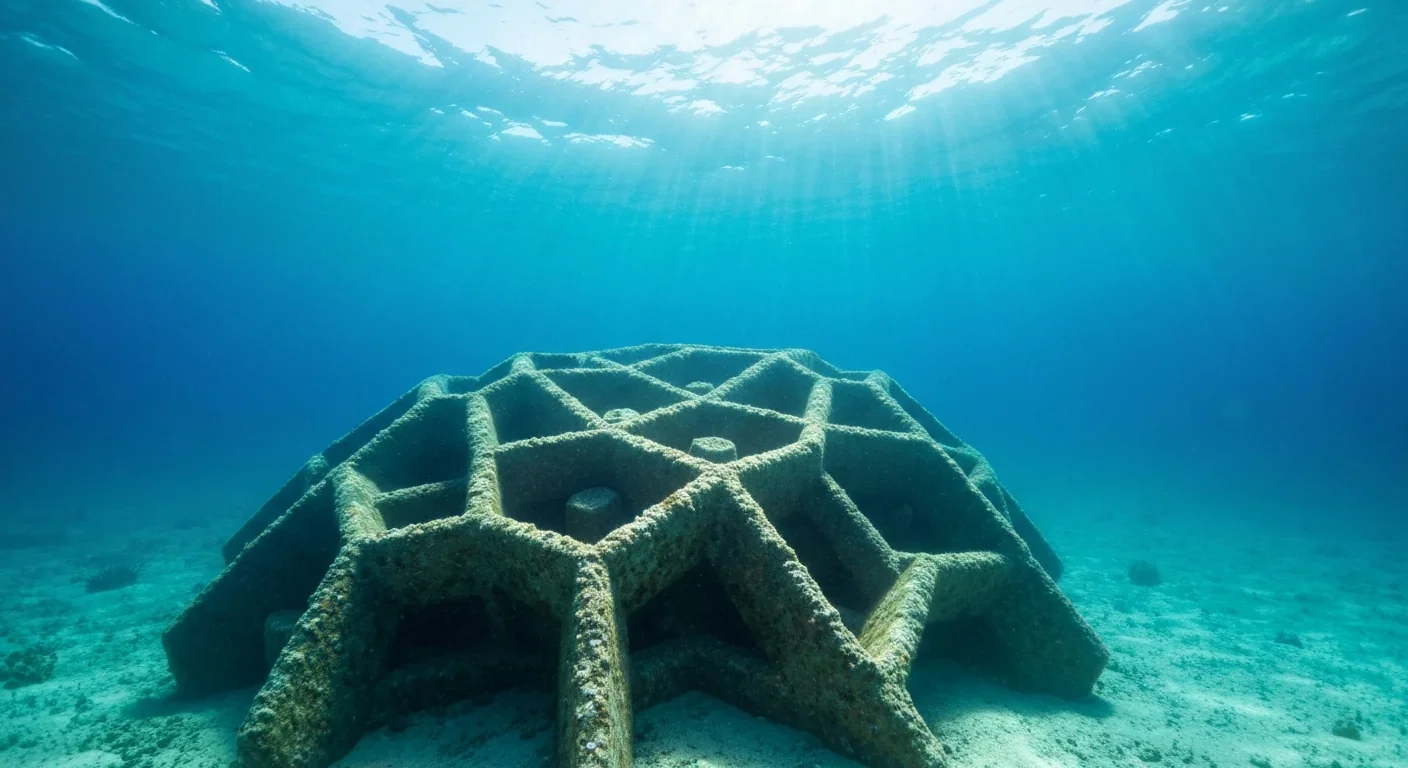

Looking forward, termite agriculture isn't just a curiosity - it's a potential blueprint. Researchers are exploring biomimetic approaches that adapt termite techniques to human-scale farming: using beneficial microbes to process crop waste, designing farm structures inspired by mound architecture, employing biological pest control methods that mirror termite chemical defenses.

Some innovators propose direct collaboration. In parts of Africa, farmers already harvest Termitomyces mushrooms from wild termite colonies, essentially letting the termites do the farming while humans collect the harvest. Could we scale this relationship, creating semi-wild fungiculture that combines termite efficiency with human harvesting?

The biotech applications are equally promising. Termitomyces enzymes could improve industrial processing of plant biomass. Antimicrobial compounds from termite gardens might yield new antibiotics. The genetic basis of termite-fungus communication could inform how we engineer beneficial relationships between crops and soil microbes.

The termite story ultimately teaches us humility. We're not the first farmers, not by a long shot. We're not even the only current farmers - several ant lineages, some beetles, and even certain fish practice forms of agriculture. What we thought was our unique achievement is actually a recurring pattern in nature, one that emerges wherever the conditions are right.

But this realization shouldn't diminish our accomplishments. Instead, it should expand our perspective. We're part of a broader phenomenon, one aspect of life's tendency to reorganize ecosystems in ways that increase resource availability. Agriculture isn't a human invention - it's an ecological strategy that we stumbled upon just like the termites did, only much more recently.

"Fungus-growing termites are highly opportunistic, capable of foraging on and digesting nearly any organic material they come across."

- Dr. Hu-Feng Li, Research Entomologist

What makes our version special isn't that we discovered farming, but how rapidly we've scaled and diversified it. In just 12,000 years, we've gone from managing a few wild plants to reshaping the entire planet's surface. Termites have been more stable, refining the same basic technique for millions of years without branching into new crops or methods.

The question now is whether we can learn from their stability. They've achieved sustainable intensification - high-density food production that lasts for millions of years. We've achieved rapid innovation but struggle with sustainability. Perhaps by studying these ancient farmers, we can find ways to combine the best of both approaches: human creativity and adaptability married to termite-proven sustainability.

The next time you see a termite mound, remember you're looking at a farm that has operated continuously for longer than most plant species have existed. These tiny farmers mastered agriculture before flowering plants dominated the Earth, before grasses spread across the continents, before the ancestors of humans even existed.

They're still farming today, in billions of colonies across the Old World, tending their Termitomyces crops with practiced precision. And if we're wise, we'll keep watching them, learning from their 30-million-year head start in the agricultural game we're still trying to master.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

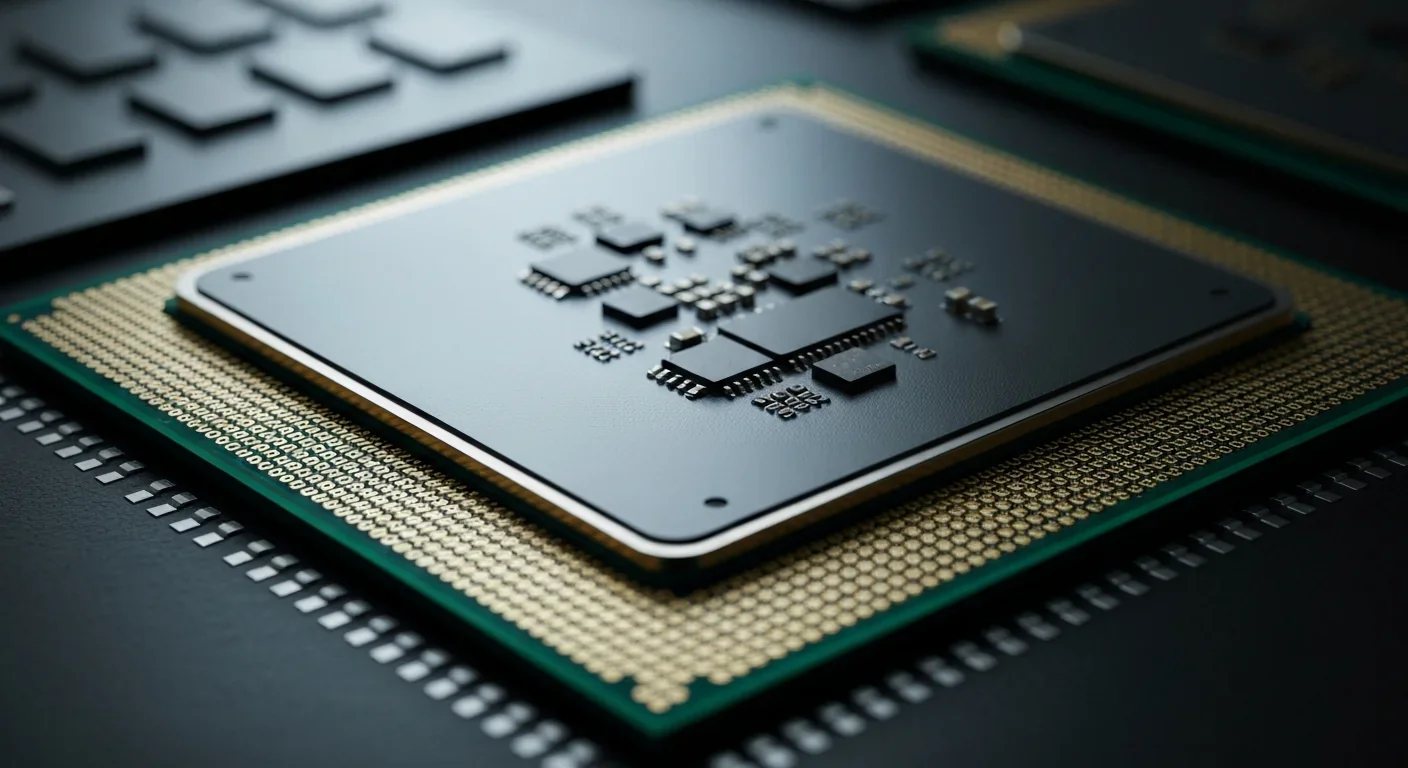

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.