Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Sperm whales communicate using distinct click dialects that mark clan membership across ocean basins. These culturally transmitted vocal traditions reveal sophisticated social learning and raise profound questions about animal intelligence, language, and conservation.

Deep beneath the waves, there's a conversation happening that humanity has barely begun to understand. Sperm whales - the largest toothed predators on Earth - don't just communicate. They speak in distinct dialects, rhythmic click patterns that mark which clan they belong to as surely as a Brooklyn accent or a Texan drawl identifies where someone's from. But unlike human regional variations, these whale dialects represent something more profound: a cultural boundary that shapes who associates with whom across entire ocean basins.

For decades, marine biologists suspected sperm whales were doing something extraordinary with their vocalizations. Now, thanks to groundbreaking research published in arXiv, scientists have quantitative proof that sperm whales maintain culturally transmitted vocal traditions - and that these traditions create social boundaries reminiscent of human ethnic or linguistic groups. The implications shake our understanding of animal intelligence, culture, and what it means to have a "language" at all.

Sperm whales create four types of clicks: standard echolocation for navigation, rapid-fire "creaks" when hunting prey, slow clicks used by males, and codas - the heart of their social communication system. Codas are short, rhythmic sequences typically containing 3 to 12 clicks arranged in stereotyped patterns, like Morse code with a beat.

What makes codas fascinating isn't their structure but their function. Individual sperm whales don't invent random click patterns. They learn specific coda repertoires from their social group, and those patterns identify which clan they belong to. Think of it like learning your native language's accent from your family - except the stakes are higher, because your dialect determines your entire social network for life.

Researchers have identified dozens of distinct coda types across global sperm whale populations. Some clans use a "5-Regular" coda (five evenly spaced clicks), while others favor "1+1+3" patterns (two single clicks followed by a triplet). These identity codas account for 35-60% of all codas a given clan produces, making them the acoustic equivalent of wearing a team jersey.

Identity codas account for 35-60% of all vocalizations a clan produces - these signature patterns are as distinctive as human fingerprints and just as permanent.

The consistency is remarkable. A sperm whale born into a clan in the eastern Pacific will produce the same identity codas as its mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother before it. DNA analysis has confirmed these clans aren't genetically distinct - they're culturally distinct, maintaining their vocal traditions through social learning across generations, much like human cultural practices pass from parent to child.

Shane Gero, a marine biologist who has spent nearly two decades studying sperm whales off Dominica, knows individual whales by name - or rather, by coda. His team has identified multiple vocal clans in the Caribbean, each with its own signature click patterns. But Dominica is just one spot in a vast ocean.

When researchers expanded their analysis to include acoustic recordings from across the Pacific and Atlantic, an extraordinary pattern emerged. The world's sperm whales aren't a homogeneous population. They're divided into vocal clans numbering hundreds or thousands of individuals, each defined by shared click dialects that remain stable over decades.

In the Pacific alone, scientists have documented at least seven distinct vocal clans, each occupying overlapping geographic ranges but maintaining acoustic separation. The Atlantic hosts its own set of clans with entirely different coda repertoires. These aren't isolated populations - whales from different clans sometimes share the same waters, hunting the same squid in the same deep trenches. Yet they maintain their distinct dialects, choosing to associate primarily with members of their own clan.

The geographic distribution challenges simple explanations. If dialects were just adaptations to local environments, you'd expect whales in similar habitats to sound alike. Instead, clans with identical coda patterns span thousands of kilometers, while clans with different dialects live side by side. It's culture, not geography or genetics, drawing the lines.

Recording sperm whale codas requires patience, technology, and a high tolerance for seasickness. Marine biologists deploy hydrophones - underwater microphones - either attached to research vessels or mounted on stationary buoys that record continuously. Some researchers use suction-cup tags that attach directly to whales, capturing the sounds individual animals make during their daily routines.

The real breakthrough came when scientists applied machine learning to analyze these recordings. Traditional analysis involved human researchers painstakingly categorizing thousands of clicks by hand, measuring intervals down to the millisecond. Modern computational methods can process vast acoustic datasets, identifying patterns too subtle for human perception.

Researchers developed a technique using variable-length Markov chain models to encode not just which coda types whales use, but the micro-variations in timing and rhythm - what they call "vocal style." It's like distinguishing not only British from American English, but London from Manchester, Brooklyn from Boston. The AI models captured these nuances with striking accuracy, correctly classifying codas to their clan of origin about 80% of the time.

"We provide quantitative evidence suggesting social learning in sperm whales across socio-cultural boundaries, using acoustic data from the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans."

- Researchers, arXiv Study on Sperm Whale Communication

One of the most ambitious efforts to decode whale communication is Project CETI (Cetacean Translation Initiative), which has deployed hundreds of high-resolution sensors off Dominica to record sperm whale conversations 24/7. The goal? Building a comprehensive database of codas in context - who said what, when, and what was happening at the time. With millions of clicks recorded, AI algorithms are beginning to identify potential grammatical rules, units of meaning, and conversational structures.

Pratyusha Sharma, a computer scientist at MIT, is using natural language processing techniques originally designed for human languages to analyze sperm whale codas. Her team has identified what might be a phonetic alphabet - discrete units that whales combine in rule-governed ways, potentially creating an open-ended communication system rather than a fixed set of signals.

The technical challenges are immense. Sperm whales often dive to depths exceeding 2,000 meters, hunting in total darkness for up to 90 minutes before resurfacing. They spend much of their lives beyond human observation, in an acoustic environment where sound travels differently than in air. Recording technology must withstand crushing pressure, saltwater corrosion, and the logistical nightmare of tracking fast-moving animals across hundreds of kilometers.

Here's where the story gets even more interesting. If vocal clans are culturally isolated groups, you'd expect their dialects to diverge completely, especially when clans share the same waters. Contact should either blur the boundaries or reinforce them. What researchers found instead was more nuanced.

A 2023 study analyzing over 10,000 codas from both sympatric (overlapping) and allopatric (separated) clan populations revealed a surprising pattern. For identity codas - the signature patterns that mark clan membership - sympatry actually increases divergence. When two clans share habitat, their identity codas become more different, not less. It's as if whales are actively maintaining acoustic boundaries to preserve group distinctiveness.

But for non-identity codas - the other 40-65% of their repertoire - the opposite happens. Clans that overlap geographically produce more similar non-identity codas than clans separated by distance. This suggests whales are learning from each other across cultural boundaries, borrowing vocal styles while fiercely protecting the markers of their own identity.

When clans share the same waters, their identity codas become MORE different, not less - they're actively maintaining cultural boundaries even as they borrow other vocal elements from neighbors.

Think of it like immigrant communities in a city. You might adopt local slang and idioms while still speaking your native language at home, maintaining the core markers of your original culture even as you absorb influences from neighbors. Sperm whales appear to do something similar, participating in a kind of acoustic multiculturalism while preserving their clan identity.

This has profound implications for understanding how whale calves learn their dialects. Young sperm whales remain with their mothers for years, far longer than most marine mammals. During this time, they're exposed to their clan's full acoustic repertoire - both the identity codas that define group membership and the flexible elements that might incorporate influences from neighboring clans.

Research suggests the learning process involves both vertical transmission (from mother to calf) and horizontal transmission (from peers and other adults). Calves practice codas obsessively, like human toddlers babbling before forming words. Gradually, their click patterns sharpen into the precise rhythms of their clan's dialect.

Mistakes have consequences. Whales that produce "foreign" identity codas risk being excluded from their social group. The acoustic penalty for mispronunciation is social isolation - a potentially fatal outcome for animals that rely on group cooperation for childcare, protection, and knowledge about foraging grounds.

The term "whale language" makes some scientists uncomfortable. Language, in the strict linguistic sense, requires specific features: discrete units (like phonemes or words), syntax (rules for combining units), semantics (meanings attached to signals), and the ability to reference things not immediately present.

Do sperm whale codas qualify? The evidence is mixed, but increasingly intriguing.

Discrete units: Check. Researchers have identified what might be a phonetic alphabet in sperm whale clicks, with codas built from combinable elements rather than holistic signals.

Syntax: Possibly. Recent AI analysis suggests codas follow sequential rules, with certain patterns more likely to follow others. Whether this constitutes grammar or just probabilistic sequencing remains debated.

Semantics: Unknown. This is the hardest part. Scientists can identify that whales use different codas in different contexts - socializing versus foraging, calm seas versus rough weather. But whether specific codas have specific meanings, or whether meaning emerges from combinations and contexts, remains unclear.

Displacement (referring to absent things): No evidence yet, though it's also the hardest feature to test in wild animals.

Hal Whitehead, a pioneer in sperm whale research, has argued for decades that sperm whales possess culture - defined as information or behavior shared within a social group through learning. By that standard, the case is clear. Sperm whale clans pass down distinct behavioral traditions, from vocal dialects to feeding techniques to migration routes, across generations through social learning rather than genetic inheritance.

Whether that culture includes language in the human sense matters less than what it reveals about whale cognition. These are animals with brains six times the size of human brains, living in complex matrilineal societies, coordinating across vast distances using acoustic signals. Recent research using AI to predict vocal exchanges found that sperm whales don't just broadcast randomly - they take turns, respond to specific codas with specific patterns, and adjust their clicking based on who's listening.

That looks a lot like conversation.

Given that sperm whale clans are defined by their dialects, what happens when whales from different clans encounter each other in the open ocean?

The answer: mostly, they avoid each other. Acoustic monitoring has revealed that when whales from different clans are in proximity, they maintain spatial separation, often by several kilometers. It's not aggressive avoidance - no reports exist of inter-clan conflict - but rather quiet segregation, like different social circles at a party.

On rare occasions, individuals from different clans do interact, particularly in areas with exceptional foraging opportunities. These encounters are brief and formal - a few codas exchanged, perhaps some close-range echolocation, then separation. There's no evidence of sustained association or friendship between individuals from different clans.

The rigidity of clan boundaries has surprised researchers. In other social mammals, like elephants or dolphins, individuals sometimes switch groups or form cross-group alliances. Sperm whales appear far more conservative, maintaining their clan identity for life. Even males, which leave their natal groups upon reaching maturity, continue using their birth clan's identity codas decades later when they return to breeding grounds.

This social structure has evolutionary advantages. By maintaining large, acoustically cohesive groups, sperm whales can share vital information across vast distances. A whale discovering a productive squid ground can signal others dozens of kilometers away. Calves separated from their mothers can broadcast distress codas that their clan will recognize and respond to. Coordinated group defense against orcas - one of the few threats adult sperm whales face - becomes possible when acoustic signals instantly unite scattered individuals.

"The more two clans overlap in geographic space, the more different their identity coda usage is."

- Researchers, arXiv Study

But the system also has fragility. If a clan's population drops below a critical threshold, the cultural knowledge it embodies - foraging techniques, migration routes, social traditions - could vanish entirely. Unlike genetic diversity, which can recover through breeding, cultural diversity once lost is gone forever.

Traditional conservation focuses on preserving genetic diversity and population numbers. The discovery of culturally distinct sperm whale clans suggests we need a new framework - one that recognizes the loss of a vocal clan as an extinction event, even if the species as a whole remains numerous.

Consider the whaling era. Industrial hunting killed perhaps 1.1 million sperm whales between 1800 and 1999. We've documented the genetic impact: reduced diversity, altered sex ratios, disrupted social structures. But what about the cultural impact?

If entire clans were wiped out - and they likely were - we've lost not just individual whales but unique dialects, behavioral traditions, and accumulated knowledge that took generations to develop. Some researchers argue this cultural genocide should factor into how we assess whale conservation status.

The implications extend to modern threats. Ship strikes, ocean noise pollution, climate change impacts on prey availability - these don't affect all clans equally. A clan whose traditional foraging grounds overlap with a major shipping lane faces different pressures than one in remote waters. Conservation strategies that treat all sperm whales as an undifferentiated population risk failing the clans most in need.

Marine protected areas could be designed around cultural units rather than just geographic features. Noise regulations might prioritize protecting areas where multiple clans overlap, preserving the acoustic contact zones where cross-cultural learning occurs.

There's even a legal dimension. If sperm whales possess culture and complex communication, do they deserve expanded legal protections? Some advocates argue for legal personhood for cetaceans, granting them rights similar to what some jurisdictions have extended to rivers or forests. The more we understand about their cognitive sophistication, the harder it becomes to justify treating them merely as resources.

Step back from the acoustic details, and the sperm whale dialect story reveals something profound about intelligence and culture in the animal kingdom. For too long, humans have treated cultural transmission as our unique achievement, the bright line separating us from "mere" animals.

Sperm whales didn't get the memo.

They've evolved complex societies built on learned traditions, where identity is culturally rather than genetically determined, where social learning creates boundaries and builds communities, where communication systems show tantalizing hints of linguistic structure. And they've maintained these cultural systems not for thousands of years, but potentially for millions - far longer than human civilization has existed.

Sperm whales have maintained cultural systems for potentially millions of years - far longer than human civilization has existed.

Other cetaceans show similar cultural complexity. Humpback whales share songs that evolve over seasons. Orcas have matrilineal cultures with distinct hunting techniques - some eat fish, some hunt seals, some specialize in sharks - passed down through generations. Dolphins have been observed teaching their young to use tools, wear sponges to protect their rostrums while foraging, and even call each other by signature whistles that function like names.

The evidence suggests cultural transmission is far more common in the animal kingdom than we assumed. It's just that most animals lack the vocal apparatus or longevity to create cultural systems we recognize as analogous to our own.

Sperm whales, living up to 70 years in stable matrilineal groups, with brains capable of processing complex acoustic information across kilometers of ocean, hit a sweet spot. They've had the time, social structure, and cognitive capacity to build something extraordinary - an ocean-spanning tapestry of vocal traditions that rivals human linguistic diversity.

The work is far from complete. Project CETI and similar initiatives continue deploying ever-more sophisticated sensors, building datasets that dwarf what was available even a few years ago. AI models grow more sophisticated, trained not just to classify codas but to understand their contextual use, predict responses, and potentially even generate synthetic codas that whales might recognize.

Some researchers envision a future where we don't just eavesdrop on whale conversations but participate in them - two-way communication between species, mediated by AI translators that bridge the acoustic gap. The ethical implications are staggering. Would we use such capability to guide whales away from danger? To ask questions about their experiences? To understand their perspective on the ocean they've inhabited far longer than we have?

Others caution against anthropomorphic projections. We risk imposing human frameworks on fundamentally alien minds, seeing language and culture where evolution produced something functionally similar but mechanistically different. The challenge is appreciating sperm whale cognition on its own terms, not as a pale reflection of human abilities but as an independent solution to the problem of social coordination in a vast, dark, three-dimensional environment.

What's certain is that every new discovery raises the ethical stakes. The more we learn about sperm whale intelligence, social complexity, and cultural sophistication, the harder it becomes to justify activities that harm them. Reducing ocean noise pollution, preventing ship strikes, addressing climate change, limiting plastic waste - these aren't just environmental issues anymore. They're questions of interspecies ethics, of how we share the planet with other intelligent, cultured beings whose societies we're only beginning to understand.

Perhaps the most important lesson from sperm whale dialects is humility. For all our technological prowess, we're only now developing the tools to perceive what these animals have been doing for eons. Beneath the waves, complex societies rise and fall, cultures flourish and fade, conversations happen in languages we can barely detect, let alone understand.

The ocean has always been full of voices. We're only just learning to listen.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

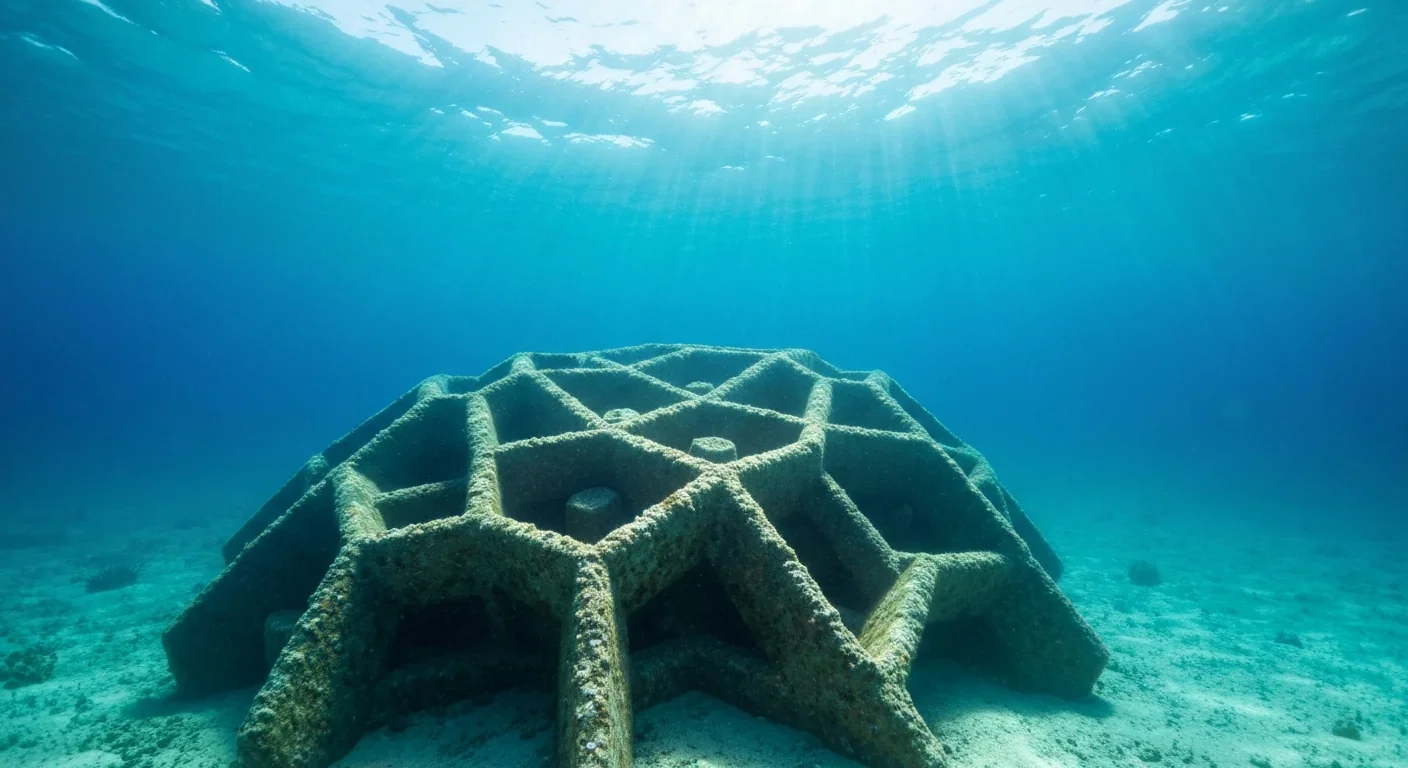

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

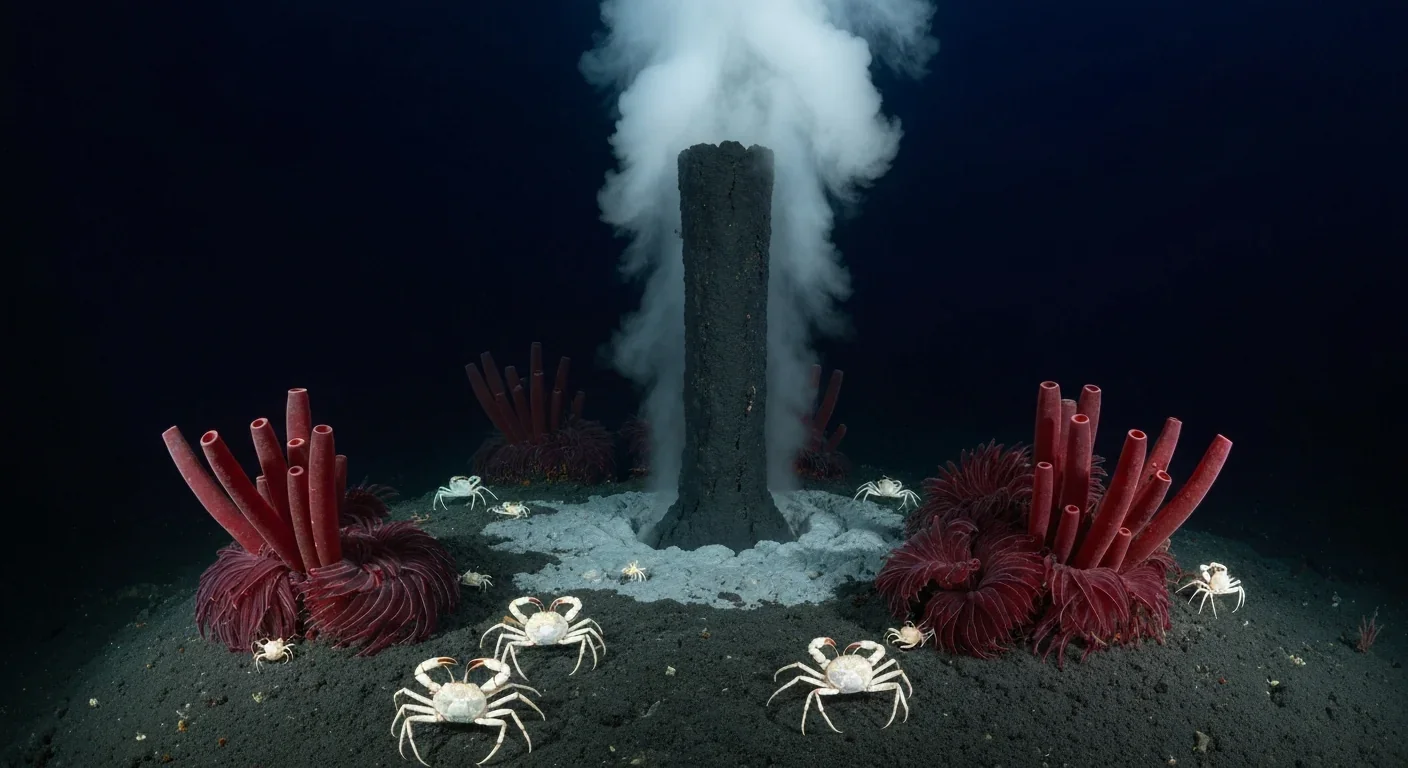

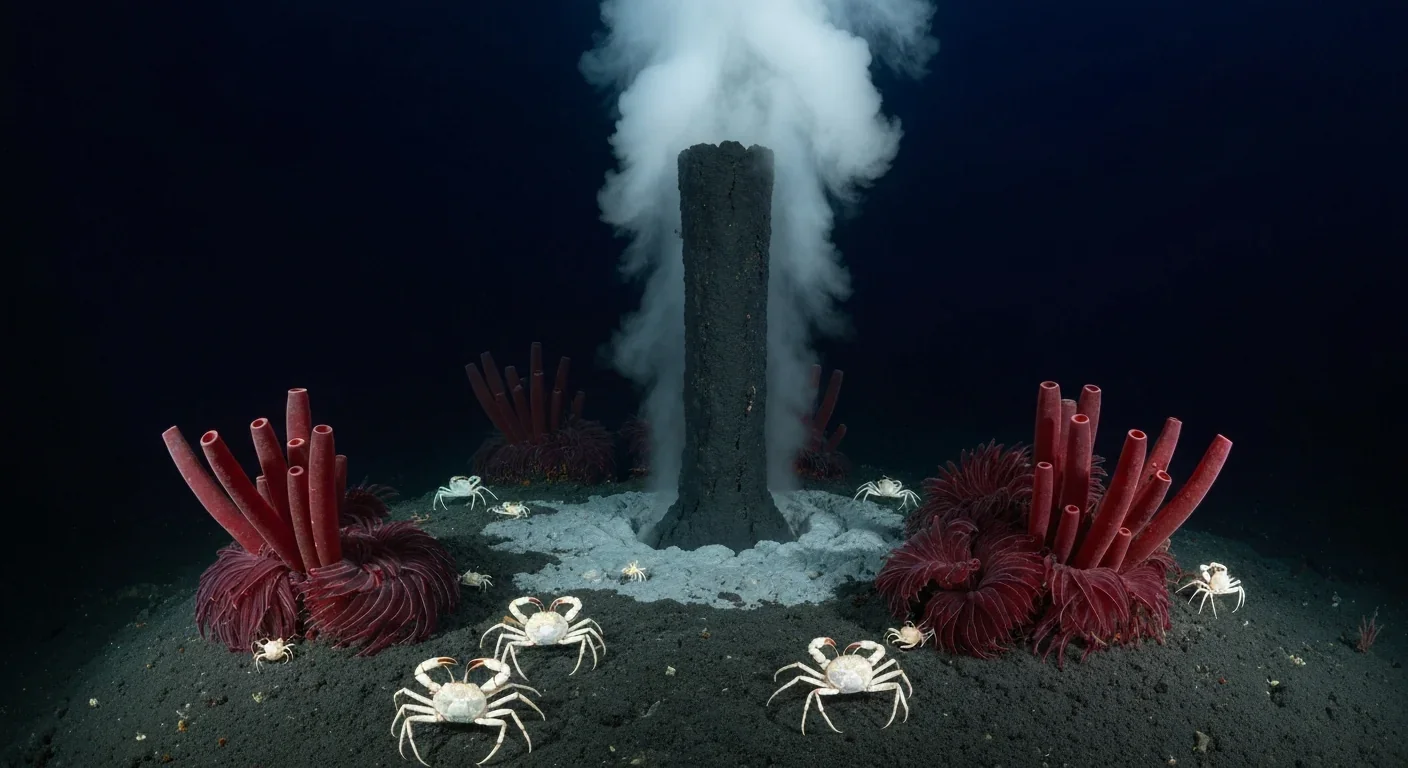

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

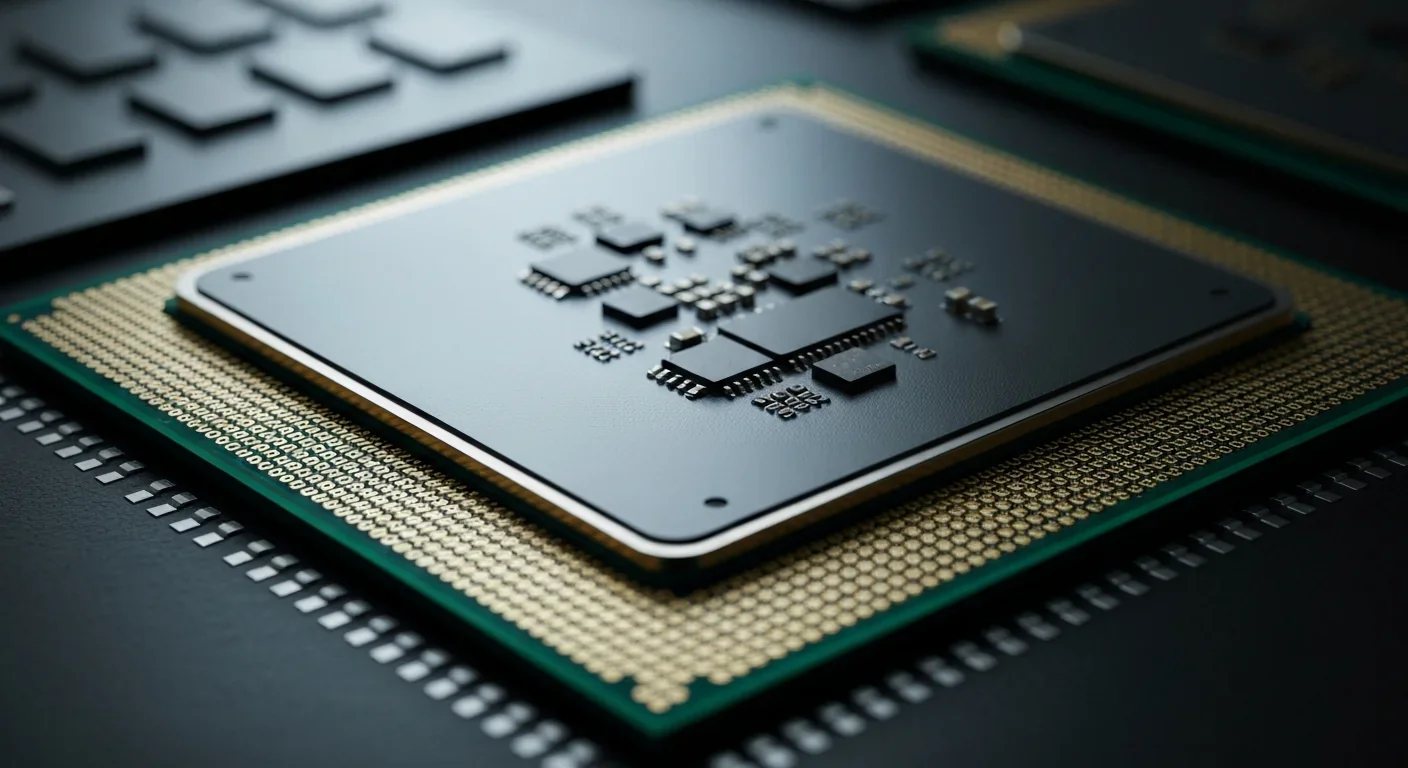

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.