Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Serpentine soil specialist plants have evolved extraordinary adaptations to thrive in toxic heavy metal environments, accumulating nickel, chromium, and cobalt at concentrations that would kill normal vegetation. These hyperaccumulators now offer revolutionary applications in phytomining and environmental cleanup.

Deep in California's coastal ranges, on hillsides that look barren to most, a silent revolution in survival is playing out. While ordinary plants wither and die in soils laced with nickel, chromium, and cobalt - metals toxic enough to kill most vegetation - a specialized group of botanical extremophiles doesn't just endure these conditions. They flourish in them, accumulating metal concentrations thousands of times higher than normal plants could tolerate. These hyperaccumulators represent one of evolution's most counterintuitive solutions: turning environmental toxins into evolutionary advantages.

What makes this even more remarkable is what scientists are now discovering about these plants. They're not merely surviving against the odds - they're potentially solving some of humanity's most pressing environmental challenges, from cleaning up contaminated industrial sites to sustainably mining metals for our technology-dependent civilization.

Serpentine soils are Earth's botanical badlands. Formed from the weathering of ultramafic rocks like peridotite and serpentinite, these soils contain concentrations of heavy metals that would be lethal to most plant life. Chromium, cobalt, and especially nickel reach levels up to a thousand times higher than typical soils.

But the toxicity doesn't stop there. Serpentine soils also suffer from critically low levels of essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. The calcium-to-magnesium ratio is severely skewed, creating a double bind: plants face both nutrient starvation and metal poisoning simultaneously.

These challenging conditions exist across surprisingly diverse landscapes worldwide. From the Balkan Peninsula to New Caledonia, from Cuba to California, serpentine outcrops create ecological islands where ordinary rules of plant survival don't apply. California alone hosts the majority of North America's serpentine soils, with smaller patches scattered along the Appalachian Mountains' eastern slope.

The result? Landscapes that appear sparse and stunted, with vegetation that looks perpetually stressed. Yet for the plants that have cracked the code, these toxic wastelands represent an opportunity.

How does a plant survive - let alone thrive - in conditions that would kill its ancestors? The evolutionary mechanisms behind hyperaccumulation represent some of nature's most sophisticated biochemical engineering.

These botanical extremophiles have developed multiple adaptive strategies working in concert. Some species employ metal exclusion, restricting uptake at the root level through selective membrane transport. Others have perfected compartmentalization, sequestering toxic metals in specific tissues - often in leaf cells called trichomes - where they can't interfere with vital metabolic processes.

A hyperaccumulator plant can accumulate more than 1,000 parts per million of nickel in its dried leaf tissue - sometimes reaching 3% of dry weight. That's roughly a thousand times the concentration found in normal plants.

The most dramatic adaptation is true hyperaccumulation. These plants don't just tolerate metals; they actively concentrate them. A hyperaccumulator plant can accumulate more than 1,000 parts per million of nickel in its dried leaf tissue - sometimes reaching 3% of dry weight or higher. That's roughly a thousand times the concentration found in normal plants.

The molecular machinery enabling this feat is elegant in its complexity. Hyperaccumulators overexpress constitutive metal transporters - proteins that actively pump metals from roots to shoots. They possess enhanced translocation capacity, moving metals rapidly through xylem tissue without triggering the stress responses that would shut down normal plants.

Once metals reach the leaves, specialized binding proteins come into play. Histidine, an amino acid, acts as a crucial nickel-binding ligand. Meanwhile, phytochelatin synthases and metallothioneins produce metal-chelating compounds that neutralize toxicity. Transport proteins then shuttle these metal complexes into vacuoles or the apoplast - cellular compartments that keep them safely away from sensitive metabolic machinery.

Perhaps most surprisingly, some hyperaccumulators have turned their toxic accumulation into a defensive weapon. Studies show that nickel accumulation in species like Thlaspi montanum provides protection against fungal and bacterial pathogens, and may even deter herbivorous insects. The plants have essentially weaponized their environment.

Over 800 hyperaccumulating plant species have been identified globally, representing an evolutionary convergence across multiple plant families. The majority come from Brassicaceae (the mustard family), Asteraceae (sunflowers), and Amaranthaceae (amaranths), though hyperaccumulation has evolved independently in at least 45 different plant families.

Nickel hyperaccumulators dominate the roster, with species like Alyssum bertolonii and Streptanthus polygaloides serving as model organisms for research. Alyssum species from Mediterranean serpentine outcrops can accumulate nickel to extraordinary levels - some specimens containing more than 3% nickel by dry weight.

In tropical regions, particularly New Caledonia's ultramafic landscapes, species like Psychotria douarrei and various Phyllanthus species have evolved remarkable nickel accumulation abilities. New Caledonia's biodiversity is particularly striking: the island's serpentine-rich geology has produced numerous endemic hyperaccumulators found nowhere else on Earth.

"Hyperaccumulators are required to demonstrate a bioconcentration factor and translocation factor greater than 1, meaning they concentrate metals in shoots at higher levels than in the soil and roots."

- Scientific definition from hyperaccumulator research

Beyond nickel, specialized hyperaccumulators tackle other metals. Noccaea caerulescens (alpine pennycress) excels at zinc and cadmium accumulation. Arabidopsis halleri has become a model organism for understanding cadmium/zinc pumping mechanisms at the molecular level. Some Sedum species, particularly Sedum alfredii, possess sophisticated cadmium efflux systems in their roots that enable high accumulation rates.

The genetic basis of hyperaccumulation is gradually being unraveled. Recent research on serpentine endemics reveals extremely fine-scale soil heterogeneity that shapes patterns of genetic diversity within populations, suggesting that hyperaccumulation traits are maintained through intense local selection pressures.

Step into a serpentine ecosystem and you're entering an ecological world unto itself. The harsh conditions create what ecologists call "islands" of specialized biodiversity - areas where evolution has produced species found nowhere else.

The serpentine grasslands of California exemplify this phenomenon. These sparse, rust-colored hillsides host plant communities radically different from surrounding landscapes. Species diversity is often lower than adjacent non-serpentine areas, but endemism is extraordinarily high. In California, roughly 45% of taxa associated with serpentine soils are rare or endangered, many existing in tiny, isolated populations.

This high endemism creates conservation challenges. Serpentine specialists often have extremely narrow geographic ranges - sometimes confined to a single hillside or valley. Their survival depends on the preservation of very specific soil conditions that took millions of years to develop.

Take the Staten Island Serpentinite outcrop in New York City - a small geological formation supporting plant species found almost nowhere else in the state. Or Maryland's Serpentine Barrens Conservation Park, protecting rare serpentine grassland communities that represent biodiversity hotspots in an otherwise temperate forest landscape.

The ecological dynamics of these systems are equally distinctive. Competition is reduced because so few species can survive, but those that do often display remarkable stress tolerance beyond just metal resistance. They've adapted to drought, poor nutrition, and intense sun exposure - conditions that accompany serpentine soils' skeletal structure and light color.

This combination of factors creates what ecologists call "barren vegetation" - plant communities that appear sparse and stunted but harbor unique evolutionary stories. From a distance, these landscapes might look degraded, but they're actually among Earth's most specialized and irreplaceable ecosystems.

What began as botanical curiosity is rapidly becoming technological revolution. Scientists and entrepreneurs are harnessing hyperaccumulators' metal-concentrating abilities for two transformative applications: cleaning polluted sites and sustainably mining metals from the ground.

Phytoremediation - using plants to remove contaminants from soil and water - represents the cleanup side of this equation. Hyperaccumulators planted on contaminated sites act as biological vacuum cleaners, pulling heavy metals from soil through their roots and concentrating them in harvestable biomass. After growing seasons, the plants are harvested and the metals can be recovered or safely disposed of at much lower volumes than traditional soil excavation would require.

The advantages of phytoremediation are compelling: it costs a fraction of traditional remediation, maintains soil structure, and even provides aesthetic benefits - a growing green cover versus scarred earth.

The advantages over conventional cleanup methods are compelling. Phytoremediation is far less disruptive than excavation, maintains soil structure, and costs a fraction of traditional remediation. It even provides aesthetic benefits - a growing green cover versus scarred earth. Projects are underway using hyperaccumulators to tackle legacy contamination from mining operations, industrial facilities, and military sites.

But the most revolutionary application is phytomining - literally farming metals from the earth. The concept: plant hyperaccumulators on naturally metal-rich soils (like serpentine), harvest the biomass, burn or compost it, and extract pure metals from the concentrated ash. The approach offers a sustainable alternative to conventional mining's environmental destruction.

Early commercial ventures are already emerging. Metalplant, a startup profiled in Chemical & Engineering News, is developing systems to farm nickel using hyperaccumulator species. The company envisions farms that produce battery-grade nickel with minimal environmental impact - no open pit mines, no toxic tailings.

Genomines, backed by venture capital, is taking a genetic engineering approach, working to enhance hyperaccumulation traits in fast-growing plant species. The goal: create optimized cultivars that maximize metal uptake and biomass production for phytomining operations.

The economics are increasingly favorable, particularly for high-value metals. A University of Florida analysis suggests phytomining could help address nickel supply challenges for electric vehicle batteries - a potentially enormous market as transportation electrifies. When you can harvest 200-300 kg of nickel per hectare annually using hyperaccumulators, the numbers start making sense.

Agromining - a related concept - combines both applications. In ultramafic regions like New Caledonia, where natural serpentine soils are abundant, agromining systems could optimize ecosystem services while producing valuable metals. The approach restores degraded serpentine landscapes while creating economic value from what's currently considered marginal land.

Despite the promise, significant hurdles remain before phytomining and phytoremediation become mainstream technologies. The challenges span biology, economics, and ecology.

Biological limitations top the list. Even the best hyperaccumulators grow slowly compared to conventional crops. They've evolved for survival in harsh conditions, not for rapid biomass production. While a corn plant rockets to maturity in months, many hyperaccumulators take a full growing season or longer to accumulate significant metal concentrations. Breeding or engineering faster-growing varieties without sacrificing accumulation capacity remains an active research frontier.

"Economic viability is uncertain. Metal prices fluctuate, and phytomining only makes financial sense when recovery costs stay below market value."

- Economic analysis from phytomining research

Economic viability is equally uncertain. Metal prices fluctuate, and phytomining only makes financial sense when recovery costs stay below market value. For abundant metals like nickel, margins are thin. For rarer metals like platinum group elements (which a few hyperaccumulators can concentrate), economics improve, but suitable species and optimal growing conditions are still being worked out.

There's also the extraction challenge. After harvest, you still need to extract pure metals from plant biomass - essentially creating a new type of ore processing. While burning biomass and refining the ash works at small scale, industrial-scale operations need optimized, economically efficient extraction methods. Current research explores everything from pyrometallurgy to bioleaching bacteria that can mobilize metals from plant material.

Environmental concerns cut both ways. While phytomining avoids traditional mining's devastation, it could impact serpentine ecosystems. Planting dense monocultures of hyperaccumulators - even native ones - on serpentine soils could displace rare endemic species adapted to those exact conditions. Large-scale operations might alter soil chemistry, hydrology, and ecological dynamics in ways we don't fully understand.

Conservation biologists worry about genetic contamination. If engineered hyperaccumulators with enhanced traits escape into wild populations, they could outcompete rare serpentine endemics. The very plants we're trying to harness could threaten the biodiversity hotspots where they evolved.

Then there are the unknowns. Long-term effects of repeatedly harvesting metal-laden biomass from soils are unclear. Does it eventually deplete even naturally metal-rich soils? How do soil microbial communities respond to decades of hyperaccumulator cultivation? What happens to arthropods and other fauna in these engineered phytomining systems?

Social dimensions matter too. In regions like New Caledonia, where nickel mining is economically vital but environmentally devastating, phytomining could offer sustainable alternatives. But transitioning entire regional economies from conventional mining to agricultural metal production involves workforce retraining, infrastructure development, and economic restructuring - changes that take decades to implement.

The future of hyperaccumulator research and application will require walking a careful line between technological innovation and ecological preservation. The plants that have evolved to survive Earth's most challenging soils offer solutions to human problems - but those solutions must not come at the cost of the ecosystems that produced these remarkable organisms.

Conservation efforts for serpentine ecosystems need to intensify. Protected areas like California's serpentine preserves and Maryland's conservation parks provide crucial refugia for rare endemics. But protection can't be passive. Active management - controlling invasive species, preventing habitat fragmentation, maintaining natural fire regimes - is essential for preserving these specialized communities.

Research priorities are evolving. Beyond simply cataloging hyperaccumulators, scientists are working to understand the molecular mechanisms at ever-finer resolution. Studies of metal transporters and chelating proteins at the genetic level could enable targeted enhancement of accumulation traits. Understanding how phytochelatins contribute to cadmium mitigation opens pathways for genetic manipulation.

There's growing recognition that serpentine systems offer natural laboratories for studying rapid evolution and local adaptation. The fine-scale genetic diversity observed in some serpentine endemics, shaped by microscale soil heterogeneity, provides insights into how evolution operates at the smallest spatial scales.

Practical applications are moving from concept to implementation. Pilot phytoremediation projects are demonstrating feasibility for specific contaminants and site conditions. Commercial ventures are refining cultivation techniques, optimizing harvest timing, and improving extraction efficiency. Within the next decade, we'll likely see phytomining operations transition from experimental plots to economically viable farms.

The cultural shift matters as much as the technology. As society grasps that plants can mine metals, clean contamination, and do so sustainably, these botanical extremophiles move from scientific curiosities to recognized problem-solvers. Botanical gardens like the UC Botanical Garden at Berkeley are showcasing serpentine specialists, educating the public about these overlooked ecosystems.

Looking further ahead, the principles learned from hyperaccumulators might extend beyond heavy metals. Could similar mechanisms be engineered for capturing rare earth elements, critical for modern electronics? Might hyperaccumulation strategies inform how we design crops for nutrient-poor or contaminated soils in a changing climate?

In serpentine soils, evolution has written a lesson about resilience and adaptation. Plants that thrive where others perish demonstrate that toxicity is context-dependent - one organism's poison is another's opportunity. The mechanisms they've evolved - transporting, chelating, compartmentalizing, even weaponizing heavy metals - represent millions of years of natural R&D.

As humanity confronts mounting environmental challenges - contaminated sites demanding cleanup, resource extraction straining ecosystems, technology requiring ever more exotic materials - these botanical extremophiles offer nature-inspired solutions. They show us that sustainability doesn't require abandoning technology or metals; it requires working with biological systems rather than against them.

The hyperaccumulators growing on California's rust-colored hillsides, New Caledonia's ultramafic ridges, and Maryland's serpentine barrens aren't just scientific curiosities. They're proof that evolution finds answers to seemingly impossible challenges, and that the natural world still holds countless solutions we're only beginning to recognize.

Understanding and harnessing these plants means seeing them not as weeds on barren land, but as sophisticated chemical engineers that have already solved problems we're only now learning to ask. The question isn't whether hyperaccumulators can help address human challenges - they demonstrably can. The question is whether we can implement these solutions thoughtfully enough to preserve the remarkable ecosystems that produced them.

In the end, the extreme survivors of serpentine soils remind us that nature operates at scales of time and sophistication we're still learning to comprehend. They're not just surviving on poison - they're thriving on it, and in doing so, showing us alternative paths forward. The real challenge is learning to walk those paths without destroying the trailblazers.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

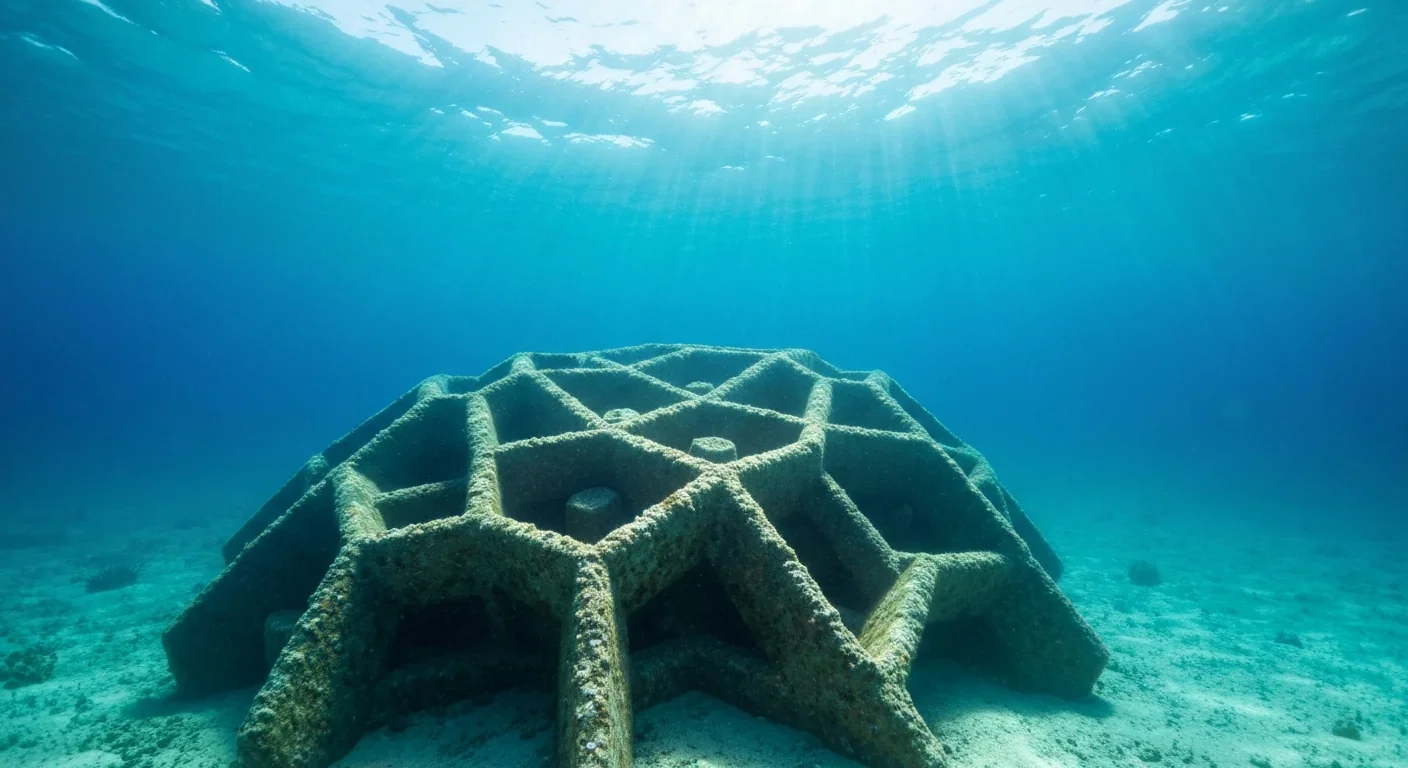

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.