Nature's First Farmers: 50 Million Years of Ant Agriculture

TL;DR: Parthenogenesis - virgin birth without males - occurs in at least 50 vertebrate species including sharks, lizards, snakes, and birds. Some species are all-female, while others switch between sexual and asexual reproduction as needed.

A female shark gives birth without ever meeting a male. A lizard lays fertile eggs in total isolation. A California condor produces offspring containing only her DNA. These aren't science fiction scenarios - they're documented cases of parthenogenesis, a reproductive phenomenon that's forcing biologists to rethink what they thought they knew about vertebrate reproduction.

For decades, the assumption was simple: complex animals need two parents. Sexual reproduction, with its genetic shuffling and mate-finding rituals, seemed non-negotiable for vertebrates. But nature, as usual, has other ideas. At least 50 vertebrate species reproduce without males, and scientists keep discovering more. What was once dismissed as impossible is now recognized as a remarkable evolutionary strategy that's been hiding in plain sight.

Parthenogenesis - from the Greek words for "virgin" and "creation" - is asexual reproduction where embryos develop from unfertilized eggs. While common in insects and some plants, it's extraordinarily rare in vertebrates. Yet it happens in sharks, rays, snakes, lizards, and even birds.

The genetic mechanisms are surprisingly diverse. In the most common type, called automixis, the egg undergoes a modified version of normal cell division. Instead of combining with sperm, the egg's genetic material duplicates or fuses with a polar body - a byproduct of egg formation - to create a diploid embryo with a complete set of chromosomes.

In parthenogenesis, an egg can duplicate its DNA or fuse with a polar body to create offspring with a complete genome - no sperm required.

There are two main flavors. Full-cloning involves premeiotic genome doubling, where the mother's DNA duplicates before division, preserving genetic diversity at most locations. This method is used by obligate parthenogenetic species like whiptail lizards, creating offspring that are near-identical copies of their mothers. Half-cloning, or terminal fusion, produces offspring that are homozygous at nearly all genetic loci - essentially, less diverse versions of mom.

The sex of parthenogenetic offspring depends on the species' chromosomal system. In XY species like most mammals, parthenogenetic offspring are always female because they inherit two X chromosomes. But in ZW species - many reptiles and birds - the outcomes vary. Offspring can be female (ZW), male (ZZ through duplication), or in rare cases like some boas, viable females with WW chromosomes.

About 50 species of lizards and one snake species reproduce exclusively through parthenogenesis. These are obligate parthenogens - populations composed entirely of females with no males anywhere in sight. The poster child for this strategy is the genus Aspidoscelis, which includes the famous New Mexico whiptail.

The New Mexico whiptail arose from hybridization between two sexual species, the little striped whiptail and the western whiptail. When these species crossed, something unexpected happened: the hybrid genome prevented healthy males from forming. What could have been an evolutionary dead end instead became a thriving all-female lineage spanning the southwestern United States and northern Mexico.

These lizards have developed a fascinating workaround for a surprising problem. While they don't need males for fertilization, they still need behavioral triggers for ovulation. Female whiptails engage in courtship and mounting behaviors with each other, with one female acting out male-typical behaviors while her partner ovulates. This "pseudosexual" behavior isn't just performative - females that don't engage in these interactions don't lay eggs. Evolution preserved the hormonal trigger mechanism even after eliminating the need for actual males.

"Those that do not 'mate' do not lay eggs."

- Research on New Mexico whiptail reproductive behavior

Similar all-female lineages exist in other reptiles. Several species of rock lizards in the Caucasus mountains, geckos in Australia, and various whiptail relatives across the Americas have all said goodbye to males entirely. Each represents an independent evolutionary experiment in female-only reproduction.

More intriguing than obligate parthenogens are facultative parthenogens - species that normally reproduce sexually but can switch to virgin birth when circumstances demand it. This reproductive flexibility has been documented in sharks, rays, Komodo dragons, turkeys, and California condors.

In October 2021, scientists at the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance made a stunning discovery. While analyzing genetic data from over 900 California condors - part of an intensive conservation program for this critically endangered species - researchers found two males that didn't match their supposed fathers. Instead, these birds carried identical copies of their mothers' DNA at all 21 genetic locations examined.

Both females had been housed with fertile males and had previously produced offspring through normal sexual reproduction. So why did they suddenly reproduce asexually? Nobody knows. The mystery deepens because facultative parthenogenesis can occur even when males are present and available, suggesting the trigger isn't simply male absence.

The condor case demonstrates why parthenogenesis in wild vertebrates might be more common than we think. "Parthenogenesis is virtually unknown in wild birds, but that could be because it's so hard to detect out in the field," explains Irby Lovette, director of the Center for Biodiversity Studies at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Without genetic testing, these virgin births look identical to normal reproduction.

Sharks have provided some of the most dramatic examples. At least three species - bonnethead sharks, blacktip sharks, and zebra sharks - have produced confirmed parthenogenetic offspring. In the most famous case, a female Atlantic blacktip shark in Virginia gave birth to a pup that DNA testing proved contained no male genetic material whatsoever.

An iguana at a Shropshire wildlife park produced eight clutches of offspring without any contact with males. "When we confirmed the eggs were fertile without any contact with a male, our jaws hit the floor," said zoo owner Scott Adams. Komodo dragons at the London Zoo and Chester Zoo both produced parthenogenetic offspring in 2006, stunning herpetologists who hadn't expected this capability in such large reptiles.

Facultative parthenogenesis acts as reproductive insurance: when males are scarce or absent, females can still produce offspring - even if those offspring are less robust than sexually produced young.

Even Burmese pythons and king cobras - snakes that normally reproduce sexually - have been documented reproducing parthenogenetically in captivity. In each case, offspring were genetic clones of their mothers, produced through variations of the meiotic process.

From an evolutionary standpoint, parthenogenesis offers one massive advantage: you don't need a mate. For species living in sparse, fragmented populations, this is huge. A single female can colonize new territory and establish a population without waiting for a male to show up. It's reproductive insurance against isolation.

The New Mexico whiptail can produce up to four eggs in midsummer, hatching about eight weeks later. Every single offspring is female and capable of reproduction, allowing populations to grow twice as fast as sexual species where half the offspring are males that don't produce eggs.

But the costs are substantial. Parthenogenetic offspring inherit either a complete or near-complete copy of their mother's genome, drastically reducing genetic diversity. This makes populations vulnerable to diseases, parasites, and environmental changes. If mom is susceptible to a particular pathogen, all her parthenogenetic daughters will be too.

The fitness consequences show up in measurable ways. Parthenogenetic geckos (Heteronotia binoei) have about 30% lower fecundity than their sexually reproducing relatives. The two parthenogenetic California condors lived only 2 and 8 years - a fraction of the typical 40-year lifespan - and neither ever reproduced.

Most shark parthenotes die before reaching maturity. When they do survive, they often show reduced vigor and abnormal development. In turkeys, where parthenogenesis can be increased through selective breeding, parthenogenetic males have smaller testes and reduced fertility.

"Both young condors lived relatively short lives of about 2 and 8 years, compared to a typical condor lifespan of more than 40 years. Neither bird produced any offspring."

- Hugh Powell, All About Birds

This is why facultative parthenogenesis makes evolutionary sense as a last-ditch strategy. When males are available, sexual reproduction provides the genetic diversity that helps populations adapt and survive. But when isolation strikes, the ability to reproduce alone - even if the offspring aren't as robust - beats not reproducing at all.

One of the most fascinating paths to obligate parthenogenesis involves hybridization between sexual species. When two different whiptail lizard species mate, their hybrid offspring sometimes cannot produce functional males due to genetic incompatibilities between the parental genomes.

Normally, this would be an evolutionary dead end. But occasionally, these all-female hybrids discover parthenogenesis, allowing them to reproduce without males. What emerges is a brand-new species composed entirely of females - a reproductively isolated lineage that can never breed with either parent species because they produce no males.

At least 15 species in the genus Aspidoscelis arose this way. Each represents an independent hybridization event that led to functional parthenogenesis. Some of these species are actually triploid - possessing three sets of chromosomes from multiple hybridization events - yet they reproduce successfully generation after generation.

Hybridization between two sexual species can accidentally create all-female lineages when the hybrid genome prevents male development but preserves female fertility.

This hybrid origin has important implications. The increased heterozygosity from combining two species' genomes may partially compensate for the genetic diversity lost through clonal reproduction. It's a one-time injection of diversity that's then maintained through full-cloning mechanisms.

Rock lizards in the genus Darevskia from the Caucasus mountains show similar patterns. Multiple all-female species arose through hybridization, each one a snapshot of an ancient cross between two sexual species. These parthenogenetic lineages have persisted for thousands of generations, defying the expectation that asexual vertebrates should quickly go extinct.

If parthenogenesis works in fish, reptiles, and birds, why not mammals? The answer lies in a genetic phenomenon called genomic imprinting. In mammals, certain genes function differently depending on whether they came from mom or dad. Some genes are only active on the paternal copy; others only on the maternal copy.

This means a mammalian embryo needs genetic contributions from both parents for normal development. An egg containing only maternal DNA lacks the necessary paternal gene expression patterns and cannot develop properly. It's an evolutionary safeguard that effectively prevents natural parthenogenesis in mammals.

However, scientists have successfully induced parthenogenesis in mice in laboratory settings. In 2022, researchers produced viable offspring from unfertilized mouse eggs by manipulating DNA methylation at seven imprinting control regions - essentially reprogramming maternal DNA to mimic the paternal pattern. The resulting mice were healthy and fertile, proving that parthenogenesis in mammals is theoretically possible if you can bypass the imprinting barrier.

This breakthrough raises intriguing questions about why mammals evolved such strong barriers to parthenogenesis when other vertebrates maintained flexibility. One hypothesis suggests that placental development requires especially precise parent-specific gene expression, making imprinting more critical in mammals than in egg-laying vertebrates.

For endangered species, parthenogenesis is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it offers a reproductive lifeline. A single female in an isolated habitat can theoretically establish a new population, buying time for conservation efforts. Several captive reptile births have demonstrated this potential.

In 2023, a captive American crocodile in Costa Rica produced a fetus that was 99.9% genetically identical to the mother - the first documented self-pregnancy in crocodiles. While the embryo didn't hatch, it proved that even large reptiles retain the capacity for parthenogenesis.

On the other hand, parthenogenesis can accelerate genetic decline in small populations. If females start reproducing asexually instead of waiting for rare mating opportunities, genetic diversity plummets. The population may grow numerically while becoming more vulnerable to disease and environmental change.

"When you have these anomalous biological phenomena, sometimes they can be used to study parts of the birds' biology that you wouldn't be able to see otherwise."

- Irby Lovette, Cornell Lab of Ornithology

The California condor case illustrates this tension. The species' breeding program maintains meticulous genetic records specifically to maximize diversity in this tiny population. Unexpected parthenogenesis, if it became common, could undermine those efforts by producing genetically identical offspring instead of diverse sexual offspring.

Wildlife managers now face new questions. Should parthenogenetic offspring be included in breeding programs? Do they represent valuable genetic material or dead ends that should be culled to preserve limited resources? For species on the brink of extinction, these aren't hypothetical debates.

Perhaps the deepest significance of vertebrate parthenogenesis is conceptual. For most of human history, sexual reproduction seemed fundamental to complex life. Two parents, genetic recombination, mate selection - these appeared to be non-negotiable requirements for vertebrate evolution.

Parthenogenesis challenges that certainty. It reveals that reproductive systems we thought were fixed can be remarkably flexible. Species can transition between sexual and asexual reproduction. All-female lineages can persist for thousands of generations. Individuals can produce offspring that are simultaneously their daughters and their clones.

"When you have these anomalous biological phenomena, sometimes they can be used to study parts of the birds' biology that you wouldn't be able to see otherwise," notes Irby Lovette. These rare cases serve as natural experiments, revealing possibilities that normal reproduction obscures.

The existence of obligate parthenogenetic vertebrates - thriving in competitive environments alongside their sexual relatives - demonstrates that asexual reproduction isn't just a desperate survival strategy. In the right ecological context, it can be a viable long-term solution.

This matters for how we think about evolution itself. If natural selection can produce vertebrate lineages that abandon sexual reproduction entirely, what other "fundamental" aspects of biology might be more flexible than we assume? How many supposedly universal rules are actually just very common options?

Modern genetics is revolutionizing our ability to detect parthenogenesis in wild populations. Before DNA testing, scientists could only confirm virgin birth in captive animals where male exposure could be definitively ruled out. Now, genetic markers can identify parthenogenetic offspring even in wild populations where mating behavior wasn't observed.

This technological advance suggests we've been dramatically underestimating parthenogenesis frequency. As more species get genetically screened - especially in conservation programs that routinely collect DNA - more cryptic cases will likely emerge. The California condor discovery only happened because researchers were examining genetic data collected for different purposes.

Future research will likely focus on identifying the triggers for facultative parthenogenesis. Why do some females switch to asexual reproduction while others in the same population don't? Is it influenced by age, health status, stress levels, or environmental conditions? Can it be induced experimentally?

Understanding these triggers has practical applications. For captive breeding programs, knowing how to prevent unwanted parthenogenesis could help maintain genetic diversity. Conversely, for species where males are critically rare, understanding how to promote facultative parthenogenesis might provide a temporary reproductive boost.

Scientists are also investigating the molecular mechanisms that determine whether parthenogenetic offspring will be viable. Shark parthenotes usually die young, but occasionally one survives and thrives. What's different about these successful individuals? Can those factors be identified and manipulated?

The story of parthenogenetic vertebrates isn't just about strange exceptions to biological rules. It's about the extraordinary diversity of life's solutions to fundamental problems. Sex and reproduction - processes that seem immutable - turn out to be far more flexible than our mammalian perspective suggests.

Those all-female whiptail lizards aren't struggling against nature. They're exploiting a viable evolutionary strategy that works for their ecological niche. The sharks and condors producing unexpected virgin births aren't making mistakes - they're expressing an ancient capacity that's been part of vertebrate biology for millions of years.

As we push more species toward extinction and fragment their habitats, parthenogenesis may become more common, emerging as a response to isolation and population crashes. Whether this represents a path to survival or a symptom of decline will vary by species and situation.

What's certain is that virgin birth in vertebrates is neither miracle nor aberration. It's evolution demonstrating once again that when reproduction is at stake, life finds a way - sometimes even without males.

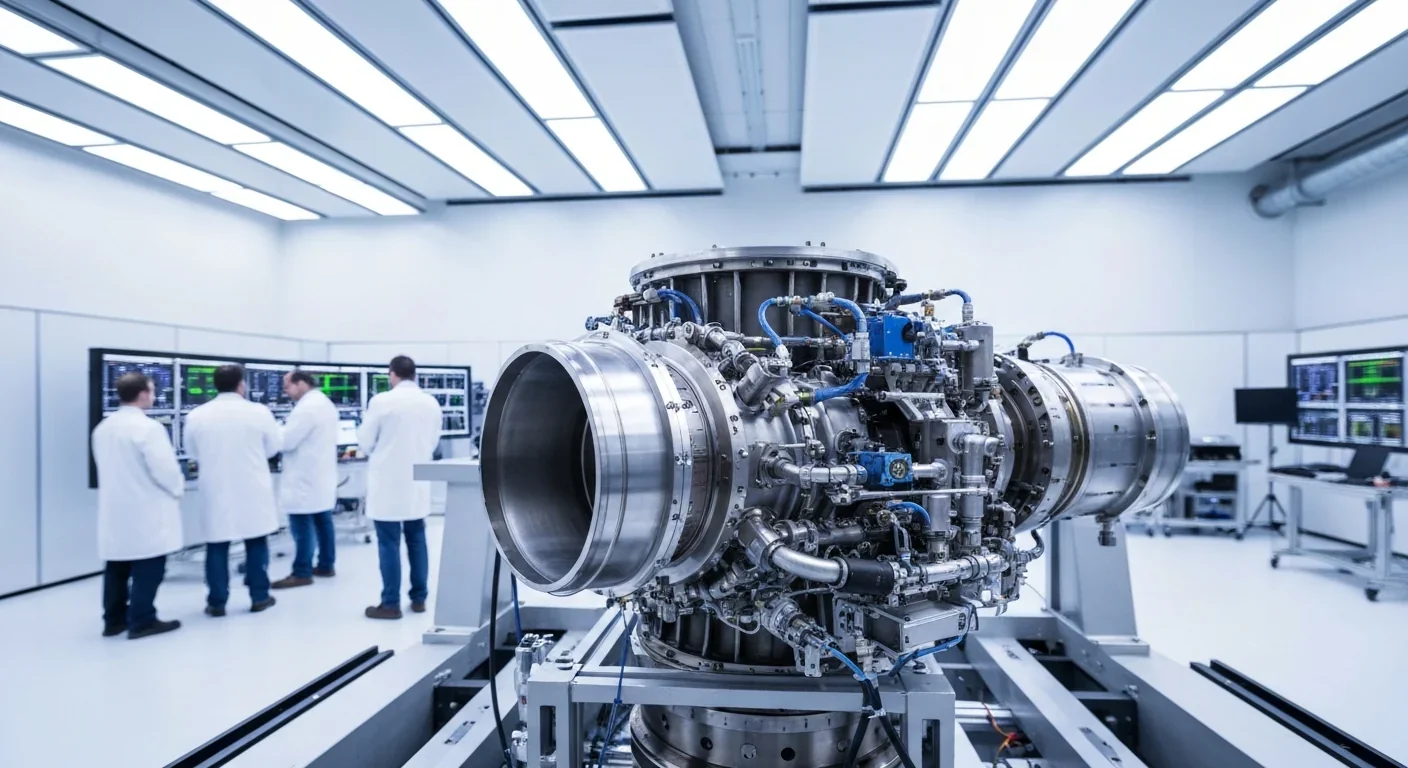

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

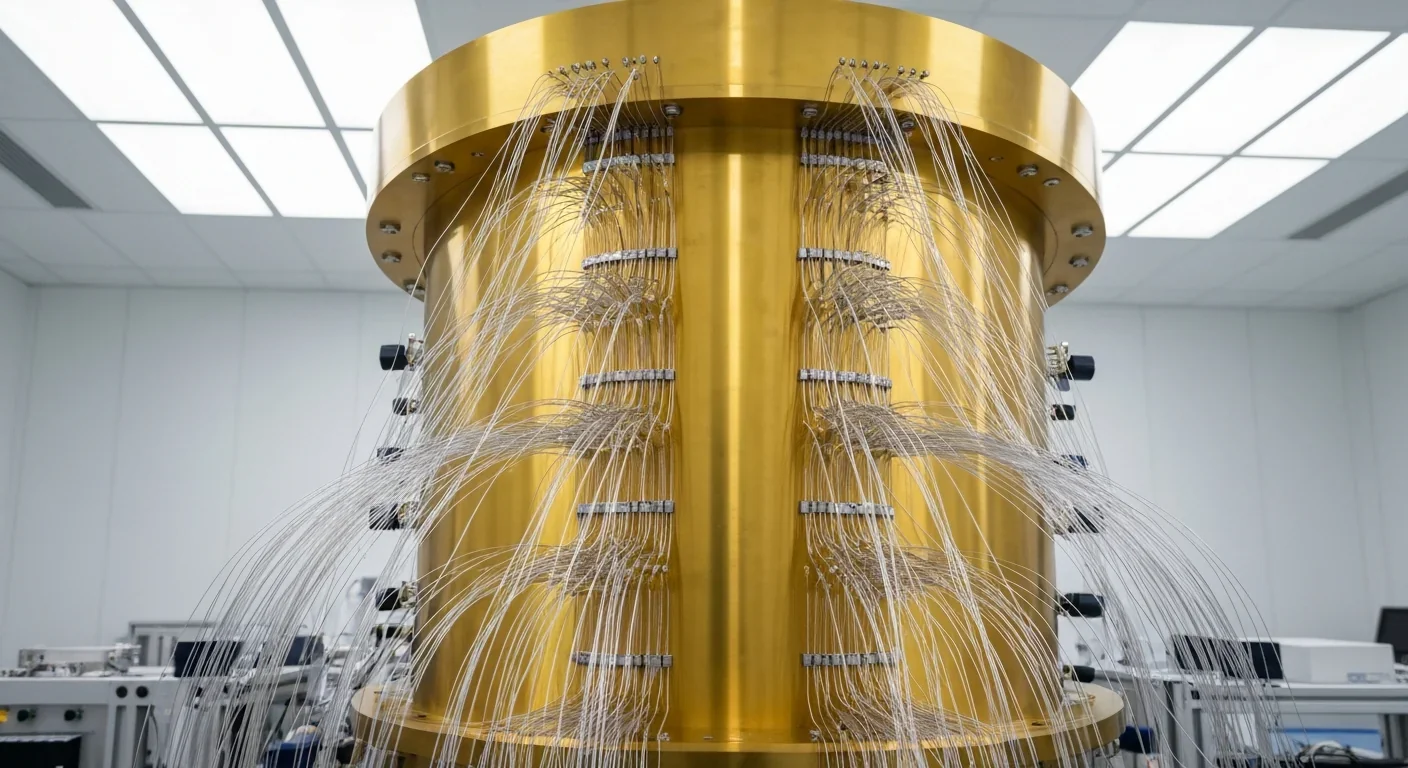

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.