Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Oilbirds are the only nocturnal, fruit-eating birds that fly, using audible echolocation clicks to navigate pitch-black South American caves. These remarkable birds evolved acoustic navigation independently from bats, demonstrating convergent evolution while maintaining the highest retinal rod density of any vertebrate for exceptional night vision.

Deep in the limestone caves of South America, a bird produces sharp clicks that bounce off rocky walls like sonar pings. The oilbird (Steatornis caripensis) has cracked a code that stumped most of the avian world: how to fly in absolute darkness without crashing into walls. While bats perfected echolocation millions of years ago using ultrasonic frequencies beyond human hearing, oilbirds independently evolved their own acoustic navigation system with one striking difference - we can actually hear their clicks.

Think of it as nature's acoustic parallel evolution. When environments present the same challenge, species from different lineages sometimes arrive at remarkably similar solutions. Oilbirds and bats both needed to navigate pitch-black environments, and both evolved the ability to "see" with sound. But the oilbird's approach is uniquely its own, operating at frequencies around 2,000 Hz - well within the range of human hearing. These clicks create an acoustic map of their environment precise enough to detect obstacles as thin as 20 centimeters while flying at speed through narrow cave passages.

This article explores how one of the world's most unusual birds developed this sophisticated sensory adaptation, what it reveals about convergent evolution, and why these cave-dwelling fruit-eaters matter to our understanding of animal cognition and sensory biology.

If you designed a bird from scratch based on conventional avian blueprints, you wouldn't create the oilbird. It violates too many rules. Birds that eat fruit are typically diurnal, relying on color vision to find ripe offerings. Nocturnal birds like owls are predators with acute hearing tuned to detect prey, not fruit. Cave-dwelling birds exist, but they're usually swiftlets making brief visits, not birds that spend significant portions of their lives in complete darkness.

The oilbird combines all these contradictions into a single species. It's the only nocturnal, flying, fruit-eating bird on Earth. Measuring up to 95 centimeters in wingspan and weighing between 350 and 475 grams, these reddish-brown birds resemble oversized nightjars but with a hooked beak more reminiscent of a hawk. That fierce-looking beak, however, is used exclusively for plucking fruit - primarily from oil palms and laurel family trees - not for tearing flesh.

The oilbird is the only nocturnal, flying, fruit-eating bird on Earth - a combination of characteristics that defies conventional avian categories.

Their appearance reflects their dual lifestyle. During daylight hours, they roost inside caves, often in colonies numbering hundreds of individuals. As dusk approaches, they emerge to forage in the rainforest canopy, using a combination of exceptional night vision and an acute sense of smell to locate fruiting trees. Then, before dawn, they return to their cave roosts, navigating pitch-black passages with echolocation clicks that create an audible symphony of acoustic orientation.

Alexander von Humboldt, the German naturalist who studied them in the early 1800s, gave them their common name after learning that Indigenous peoples in Venezuela harvested the extraordinarily fat chicks for their oil-rich tissues. The chicks were rendered for cooking fat and torch fuel, a practice that influenced both the bird's name and its cultural significance in local communities. Locally, they're known as "guácharo," a name that echoes through cave systems wherever these birds make their homes.

To understand what makes oilbird echolocation remarkable, we need to grasp the basic physics. Echolocation is essentially active sensing through sound. An animal produces a sound, that sound travels through air until it hits an object, then the echo returns. By measuring the time delay and characteristics of returning echoes, the brain constructs a spatial map of the environment.

Bats, the most famous echolocators, typically use ultrasonic frequencies between 20,000 and 200,000 Hz - far above the roughly 20 to 20,000 Hz range humans can hear. Higher frequencies provide better resolution for detecting small objects like flying insects but don't travel as far through air. Bats hunting tiny prey in open air benefit from this trade-off.

Oilbirds operate in a fundamentally different acoustic landscape. Their clicks are centered around 2,000 Hz, firmly in the audible range for humans. These lower-frequency clicks sacrifice some resolution but travel farther and reflect more effectively off the large, solid surfaces that matter most in a cave environment: walls, stalactites, rock formations, and passage openings.

Research by Donald Griffin in the 1950s first scientifically documented oilbird echolocation, establishing these birds as one of only two groups of birds known to navigate by sound (the other being cave swiftlets). Subsequent studies revealed the sophistication of their system. Oilbirds can detect and avoid obstacles as thin as 20 centimeters in diameter while flying in complete darkness - a level of precision that requires not just producing clicks but processing returning echoes with remarkable speed and accuracy.

"Oilbirds produce a high-pitched clicking sound of around 2 kHz that is audible to humans."

- Wikipedia: Oilbird

Unlike bats, which produce echolocation calls using specialized laryngeal structures, oilbirds vocalize short pulses that are audible to human observers as sharp, repetitive clicks. When hundreds of oilbirds share a cave roost, the combined effect creates a cacophony of overlapping clicks and harsh screams that early cave explorers described as otherworldly.

Processing echolocation information requires significant neural hardware. The oilbird's brain has evolved specialized adaptations to make sense of acoustic echoes in real time. While we don't yet have complete brain imaging studies comparable to those conducted on bats, behavioral evidence points to sophisticated auditory processing centers.

Consider what must happen in the fraction of a second between producing a click and adjusting flight based on the echo. The brain must filter the outgoing click from incoming echoes, calculate time delays corresponding to different distances, distinguish echoes from different surfaces (rock, wood, other birds), and translate that information into motor commands that adjust wing position and flight trajectory. All of this happens continuously while the bird flies at speeds sufficient to cover distances between cave roosts and distant fruiting trees - potentially several kilometers.

Oilbirds also possess extraordinary visual adaptations that complement their echolocation. Their retinas contain approximately one million rods per square millimeter - the highest rod density known in any vertebrate. Rods are the photoreceptor cells responsible for vision in low-light conditions, and this exceptional density gives oilbirds night vision comparable to that of owls. This dual sensory strategy - acoustic navigation inside caves, visual foraging outside - represents an elegant solution to the challenges of their ecological niche.

Oilbird retinas contain one million rods per square millimeter - the highest density known in any vertebrate, giving them night vision that rivals owls.

Research into oilbird cognition suggests they may create mental acoustic maps of familiar cave systems, similar to how humans develop spatial memories of frequently traveled routes. Young oilbirds likely learn the acoustic signatures of their home caves through repeated exposure, gradually building the neural representations that allow rapid, confident navigation even in complete darkness.

The independent evolution of echolocation in bats and oilbirds exemplifies convergent evolution - the process by which unrelated organisms develop similar adaptations in response to similar environmental pressures. Bats and birds diverged evolutionarily over 300 million years ago, yet both lineages arrived at acoustic navigation when faced with the challenge of operating in darkness.

Only two groups of birds echolocate: oilbirds and cave swiftlets. Both nest in caves, both navigate in darkness, and both evolved click-based echolocation systems. Yet even between these two bird groups, the systems differ. Cave swiftlets use even simpler, lower-resolution clicks primarily for avoiding collisions in cave entrances and passages, while oilbirds employ a more sophisticated system for extended cave dwelling.

What makes convergent evolution fascinating isn't just that different animals solve the same problem, but that they solve it differently. Bat echolocation uses ultrasonic frequencies, specialized laryngeal mechanisms, and highly directional calls. Oilbird echolocation uses audible-frequency vocalizations, broader sound patterns, and integration with exceptional night vision. Both work, but each reflects the unique evolutionary history and ecological constraints of its lineage.

The fact that echolocation evolved independently at least three times among vertebrates - in bats, oilbirds, and toothed whales - suggests it's a relatively "accessible" evolutionary innovation when the environmental pressure is strong enough. Unlike growing wings or developing a completely novel sense organ, echolocation builds on existing capabilities: vocalization and hearing. The evolutionary modifications required are substantial but not insurmountable, which explains why multiple lineages stumbled onto this solution.

If you imagine oilbirds spending their entire lives huddled in cave darkness, research suggests a more nuanced picture. A 2009 study challenged the assumption that these birds exclusively roost in caves. Researchers found that oilbirds actually spend only about one-third of their time in cave environments. The remainder of their daily cycle is spent roosting quietly in rainforest trees where they regurgitate the seeds from consumed fruits.

This discovery reframes our understanding of oilbird ecology. Rather than obligate cave-dwellers that make brief foraging flights, they're rainforest birds that use caves as colonial nesting sites and safe daytime refuges. Their echolocation isn't constantly active throughout their lives but deployed strategically when navigating cave systems - particularly the narrow, winding passages leading to deep interior nesting chambers where hundreds of birds nest colonially.

Inside caves, oilbirds establish hierarchical roosting and nesting areas. Prime nesting ledges in the deepest, most protected cave chambers are typically occupied by established breeding pairs. These locations offer maximum protection from predators but present the greatest navigation challenges, requiring birds to fly hundreds of meters through twisting passages in complete darkness. Less desirable roosting spots near cave entrances are easier to access but offer less security.

"Individuals were observed sitting quietly in trees in the rainforest where they regurgitate seeds."

- 2009 Study on Oilbird Behavior

The colonial nesting strategy creates acoustic challenges. With hundreds of birds simultaneously echolocating in an enclosed stone chamber, how does an individual bird distinguish its own echoes from the cacophony of clicks produced by neighbors? Research on bat colonies facing similar challenges suggests animals develop individual acoustic signatures - subtle variations in click frequency or timing that help each bird track its own echoes. Whether oilbirds employ similar strategies remains an active area of investigation.

Breeding biology adds another layer of complexity. Oilbirds lay relatively small clutches - typically two to four eggs - and have an extended parental care period. Chicks remain in the nest for up to four months, during which time adults make nightly foraging flights to gather fruit. This extended development period allows young birds to grow exceptionally fat, the characteristic that made them valuable to Indigenous peoples and gave the species its common name.

Oilbirds occupy a unique trophic position as specialized frugivores. Their diet consists almost entirely of the oil-rich fruits of palms and laurel family trees, supplemented occasionally by fruits from other tropical species. This dietary specialization links their survival directly to the health of tropical forest ecosystems.

Locating fruit in the dark rainforest canopy requires a different sensory toolkit than navigating caves. Visual cues become more important outside cave systems, where exceptional night vision allows oilbirds to spot fruiting trees against the night sky. Some research suggests they may also use olfactory cues to detect ripe fruit from considerable distances, though this capability remains less well documented than their visual and acoustic abilities.

The relationship between oilbirds and fruiting trees operates as an ecological partnership. Trees provide nutrition; birds provide seed dispersal services. When oilbirds consume fruit, they typically swallow it whole, digesting the oily flesh but leaving the large seed intact. These seeds are later regurgitated - either during forest roosting sessions or back in cave systems. This dispersal pattern means seeds often end up far from parent trees, potentially colonizing new areas.

Oilbirds serve as critical seed dispersers for oil palms and laurel trees, swallowing fruits whole and regurgitating seeds far from parent trees.

However, this mutualistic relationship creates conservation vulnerabilities. If fruiting trees decline due to deforestation, oilbird populations lose critical food sources. Conversely, if oilbird populations crash, some tree species lose their primary seed dispersers. These cascading dependencies mean protecting oilbirds requires protecting intact rainforest ecosystems, not just cave habitats.

The nutritional demands of flight, reproduction, and maintaining body temperature in cool cave environments mean adult oilbirds must consume substantial quantities of fruit nightly. Estimates suggest individual birds may forage across territories spanning several kilometers, visiting multiple fruiting trees each night. This ranging behavior means even protected cave sites may not ensure population viability if surrounding forests are degraded.

Oilbirds inhabit a discontinuous range across northern South America, from Venezuela to Bolivia, including Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil, Guyana, and Trinidad. Their distribution closely follows the occurrence of suitable cave systems within or near tropical rainforest habitats that contain their required fruit species.

Not every cave will suffice. Oilbirds show strong preferences for caves with specific characteristics: deep chambers accessed through narrow passages, stable microclimates with high humidity, and locations within flight range of productive fruiting trees. The largest known colony, at Cueva del Guácharo National Park in Venezuela, hosted approximately 15,000 birds as of 2015, making it one of the most important oilbird sites globally.

Their altitudinal range extends from sea level to 3,400 meters, demonstrating considerable ecological plasticity. Populations at different elevations likely specialize in different fruit species, tracking the composition of local forest communities. This altitude flexibility suggests oilbirds could potentially shift their ranges in response to climate change, assuming suitable cave systems and food resources exist at new elevations.

Human activities create complex challenges for oilbird habitat. Caves are vulnerable to disturbance from tourism, mining, and agricultural expansion. Even seemingly benign activities like cave exploration can disrupt breeding colonies if conducted during sensitive periods. Light pollution from nearby development may affect the timing of emergence and return flights. Road construction can fragment foraging ranges, forcing birds to cross dangerous gaps between forest patches.

The IUCN Red List currently classifies oilbirds as Least Concern as of 2016, but this designation masks concerning trends. The assessment notes population declines across portions of the species' range, driven primarily by habitat loss and cave disturbance.

Historical exploitation for their fat has largely ceased, but new threats have emerged. Deforestation throughout South America reduces the availability of fruiting trees, particularly the oil palms and laurel species that comprise their primary diet. Climate change may alter the phenology of fruiting events, potentially creating temporal mismatches between breeding seasons and food availability. Cave microclimate changes due to regional warming could affect nesting success.

Several South American countries have established protected areas that include important oilbird caves, but enforcement remains inconsistent. Cueva del Guácharo National Park in Venezuela represents a conservation success story, providing legal protection to the largest known colony while also accommodating regulated ecotourism that generates revenue for local communities.

The species' relatively slow reproductive rate makes populations vulnerable to rapid decline if adult mortality increases. With only two to four chicks per breeding attempt and extended parental care requirements, oilbird populations cannot quickly rebound from population crashes. This demographic constraint means proactive conservation measures are essential - waiting until populations crash dramatically may doom recovery efforts.

Conservation biologists studying oilbirds emphasize the importance of landscape-scale protection. Preserving cave sites alone isn't sufficient; conservation strategies must encompass surrounding forest ecosystems that provide food resources and roosting sites. This integrated approach requires coordination between protected area managers, forestry departments, and local communities whose livelihoods depend on forest resources.

Despite growing scientific interest, fundamental questions about oilbird biology remain unanswered. How precisely do they process acoustic information in noisy colonial cave environments? Do individuals develop personalized acoustic signatures that help them track their own echoes among hundreds of simultaneous clicks?

The role of olfaction in fruit detection remains poorly quantified. While anecdotal evidence and some preliminary research suggests oilbirds may use smell to locate fruiting trees from several kilometers away, controlled experiments testing olfactory capabilities are lacking. If confirmed, this would add another sensory dimension to their already impressive perceptual toolkit.

Genetic studies could illuminate the evolutionary history of echolocation in birds. Comparing the genomes of oilbirds, cave swiftlets, and non-echolocating relatives might identify the specific genetic changes that enabled acoustic navigation. Such research would complement similar work in bats and toothed whales, potentially revealing universal principles about how complex sensory systems evolve.

Climate change impacts require urgent investigation. As temperature and precipitation patterns shift across South America, how will fruiting tree phenology respond? Will oilbirds track these changes by adjusting their breeding timing, or will mismatches emerge? Can populations shift to higher elevations or latitudes if current ranges become unsuitable, or are they constrained by cave availability?

The social dimensions of colony life deserve deeper study. How do hierarchies form within breeding colonies? Do birds exhibit site fidelity, returning to the same caves year after year? How do young birds disperse and locate new colonies? These behavioral questions have direct conservation implications, particularly for understanding how populations might respond to disturbance or habitat loss.

The oilbird's story offers profound insights into how evolution solves complex environmental challenges. When faced with the problem of navigating in darkness, life doesn't follow a single blueprint. Instead, multiple lineages arrived at variations on the same theme, each shaped by ancestral constraints and ecological contexts.

Echolocation in oilbirds emerged from the raw materials available: vocalization, acute hearing, and a brain capable of processing temporal information. These components existed before echolocation appeared; evolution repurposed and refined them into an integrated navigation system. This pattern - building new capabilities from existing structures - characterizes much of evolutionary innovation.

The fact that oilbirds combine echolocation with exceptional night vision challenges simplistic narratives about sensory trade-offs. We often assume that specialization in one sensory modality comes at the expense of others, yet oilbirds maintain world-class capabilities in both acoustic and visual domains. This sensory diversity likely reflects their dual lifestyle, requiring different perceptual tools for cave navigation and forest foraging.

Perhaps most remarkably, oilbirds demonstrate that evolutionary innovations don't need millions of years to reach sophisticated functionality. The oilbird lineage split from other bird groups relatively recently in evolutionary terms, yet their echolocation system performs well enough to enable their unique lifestyle. This suggests that when selective pressure is strong and the necessary raw materials exist, evolution can work surprisingly fast.

The next decades will determine whether oilbirds continue to click through South American caves for millennia to come or join the growing list of species whose populations have collapsed to critical levels. The trajectory depends largely on human choices about forest conservation, climate action, and protected area management.

Success stories exist. Well-managed cave colonies in national parks prove that oilbirds can coexist with human activities when protections are enforced and local communities benefit from conservation. Ecotourism centered on oilbird caves generates revenue while raising public awareness about these remarkable birds, creating economic incentives for protection.

But these bright spots remain scattered across a landscape of intensifying pressure. As South American human populations grow and development expands into remaining wildlands, the forests that sustain oilbirds continue to shrink. Without strengthened conservation efforts, we risk losing not just a charismatic species but an irreplaceable example of evolutionary innovation - a bird that hears its way through darkness, carrying seeds between forest and cave, connecting ecosystems through sound and flight.

The oilbird's acoustic clicks represent more than a biological curiosity. They're echoes of deep evolutionary history, demonstrations of convergent evolution in action, and reminders that nature's solutions to environmental challenges often exceed human imagination. In protecting these birds, we preserve not just a species but a window into how life adapts, innovates, and perseveres against odds that would seem insurmountable. That's worth listening to.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

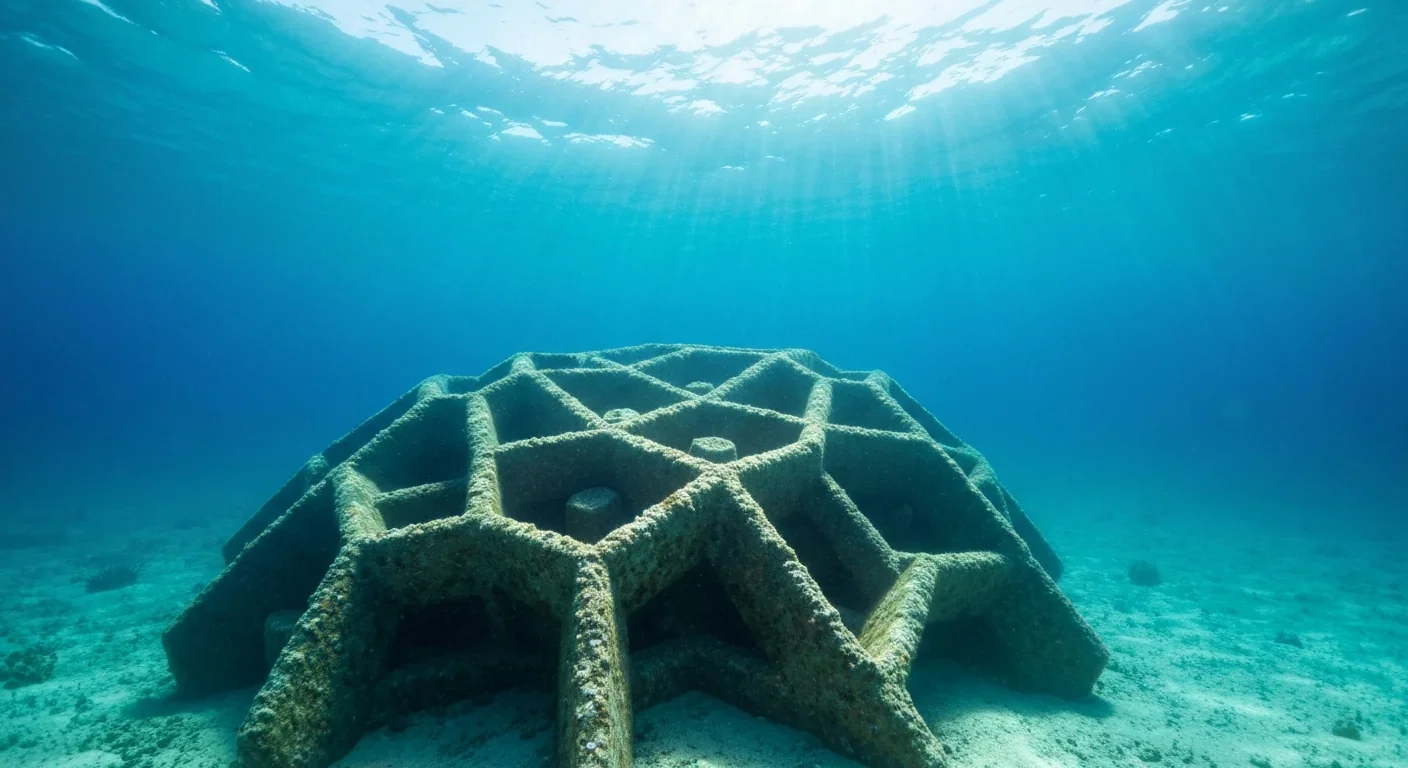

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

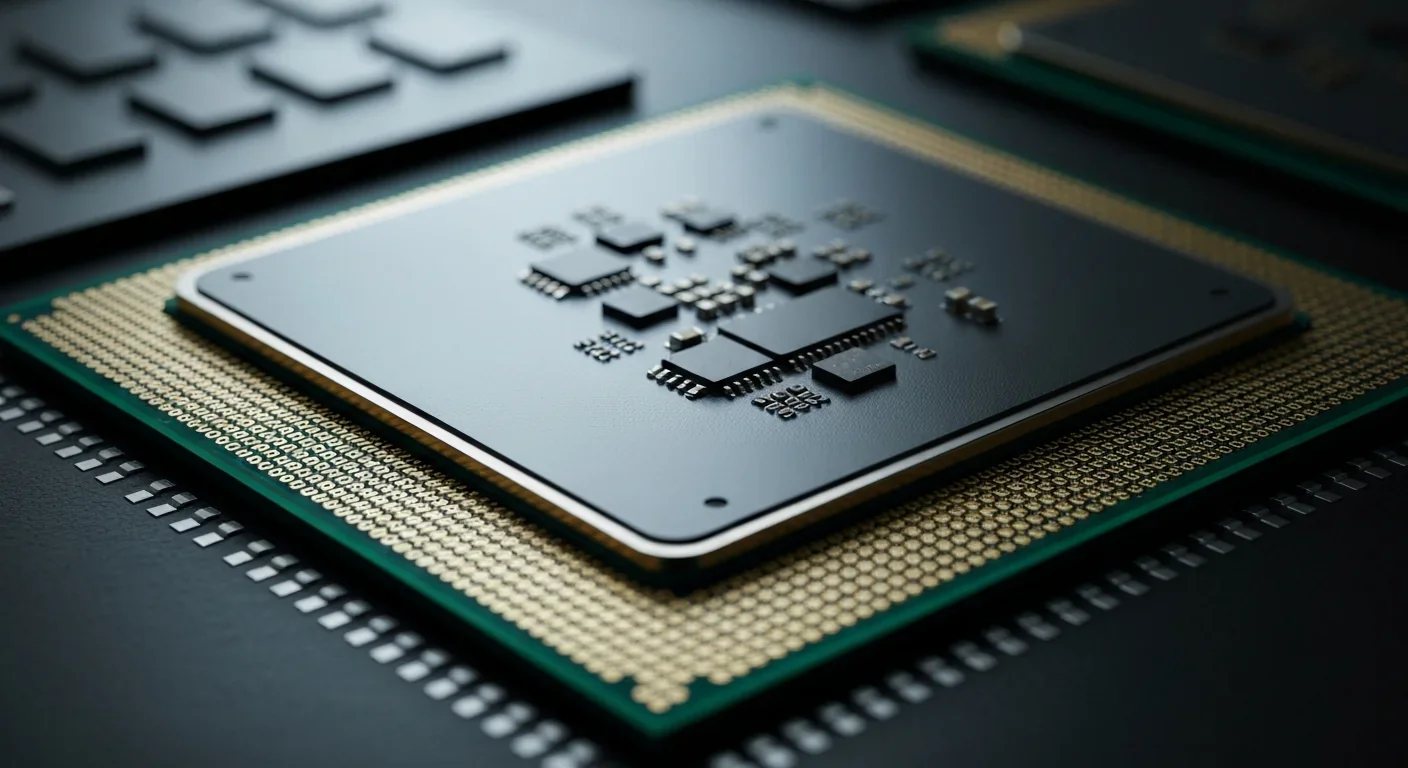

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.