Nature's First Farmers: 50 Million Years of Ant Agriculture

TL;DR: Lungless salamanders have evolved to breathe entirely through their skin, thriving in cold mountain streams without lungs. This remarkable adaptation makes them vulnerable to climate change and pollution.

Picture a salamander living in the rushing waters of an Appalachian mountain stream, never once surfacing for air. This isn't because it can hold its breath for extraordinary lengths of time. Instead, this remarkable creature belongs to the Plethodontidae family, the largest group of salamanders on Earth with over 500 species that have completely abandoned the use of lungs. These amphibians have mastered one of nature's most audacious evolutionary experiments: breathing entirely through their skin.

In cold mountain streams from British Columbia to Brazil, lungless salamanders thrive in environments where most vertebrates would suffocate within minutes. They've traded their lungs for an intricate network of blood vessels just beneath paper-thin skin, transforming their entire body surface into a living, breathing organ. This extraordinary adaptation represents over 70% of all salamander species worldwide, making lung-breathing salamanders the minority in their own taxonomic order.

The physiological feat that allows lungless salamanders to survive without lungs centers on cutaneous respiration, a process where gas exchange occurs directly through the skin. Unlike humans who rely on specialized respiratory organs, these salamanders have evolved skin so remarkably thin and vascularized that oxygen molecules can pass directly from the surrounding water or air into their bloodstream.

Research shows that approximately 83% to 93% of a lungless salamander's oxygen uptake occurs through the skin, with the remaining percentage absorbed through the moist tissues lining their mouth. This efficiency rivals that of many lung-breathing vertebrates, but it comes with strict requirements. The skin must remain perpetually moist because the gas exchange process depends on oxygen dissolving in the thin film of water or mucus covering the salamander's body.

The secret to this remarkable efficiency lies in the salamander's unique skin structure. Scientists have discovered that their epidermis is extraordinarily thin, sometimes only a few cell layers thick, allowing gases to diffuse rapidly. Just beneath this delicate outer layer, a dense network of capillaries brings blood remarkably close to the surface. Some species have capillaries that come within micrometers of the skin's surface, creating one of the shortest diffusion distances found in any vertebrate respiratory system.

To maintain the moisture essential for gas exchange, plethodontid salamanders possess specialized features including costal grooves that run along their bodies. These grooves act like tiny channels, helping to distribute and retain water across the skin surface through capillary action. If their skin dries out, these salamanders face immediate suffocation, making them entirely dependent on humid environments for survival.

A lungless salamander's skin must remain perpetually moist - if it dries out for even a few minutes, the animal will suffocate, unable to absorb the oxygen it needs to survive.

The complete loss of lungs in an entire family of vertebrates raises profound questions about evolutionary pressures and advantages. Recent fossil discoveries and molecular studies suggest that the evolutionary journey toward lunglessness began millions of years ago when salamander ancestors inhabited fast-flowing mountain streams.

In these turbulent waters, lungs became more liability than asset. Evolutionary biologists theorize that buoyancy from air-filled lungs made it difficult for salamanders to maintain position in strong currents. Those individuals with smaller lungs could better anchor themselves to stream bottoms and navigate rocky substrates without being swept away. Over countless generations, natural selection favored salamanders with progressively reduced lung tissue until the organs disappeared entirely.

Remarkably, research from Harvard University reveals that lungless salamanders still develop lung buds as embryos, which are then reabsorbed during development. This vestigial trait provides compelling evidence that these species descended from lung-breathing ancestors. The genes for lung development remain in their DNA, but regulatory changes prevent these structures from forming in adults.

The shift from aquatic larvae to direct development played a crucial role in enabling complete lung loss. Many plethodontid species bypass the aquatic larval stage entirely, with embryos developing directly into miniature adults inside terrestrial eggs. This freed them from the constraints of aquatic gill breathing during youth and aerial lung breathing as adults, allowing cutaneous respiration to become their sole gas exchange method throughout their entire life cycle.

The cold, oxygen-rich waters of mountain streams provide ideal conditions for cutaneous respiration. Studies show that cold water holds significantly more dissolved oxygen than warm water, with oxygen concentrations in mountain streams often reaching 11-14 milligrams per liter compared to just 7-9 milligrams in warmer lowland waters.

Appalachian brook salamanders represent some of the most successful mountain stream specialists. These species inhabit elevations up to 1,500 meters, where water temperatures rarely exceed 15°C (59°F). The combination of high oxygen content and low temperatures reduces their metabolic demands while maximizing oxygen availability, creating perfect conditions for skin breathing.

"Cold water can hold nearly twice as much dissolved oxygen as warm water, which is why mountain streams are the perfect habitat for lungless salamanders."

- Dr. Emily Harrison, Appalachian State University

Temperature plays a critical role in salamander survival. As water temperature increases, dissolved oxygen decreases while metabolic rates rise, creating a dangerous scissors effect. A lungless salamander in 10°C water might thrive with minimal effort, but the same individual in 20°C water could struggle to extract enough oxygen to meet its metabolic needs.

The physical structure of mountain streams further benefits these specialized amphibians. Cascading water over rocks creates turbulence that constantly replenishes oxygen levels at the water's surface. Salamanders position themselves in splash zones and along stream edges where this oxygen-rich water flows over their skin. Some species have evolved flattened bodies and enlarged limbs that increase surface area for gas exchange while helping them cling to wet rocks in strong currents.

Living without lungs imposes severe limitations on body size, activity levels, and habitat choice. The largest lungless salamander, Bell's false brook salamander, reaches only 36 centimeters (14 inches) in length, while lung-breathing salamanders like the Chinese giant salamander can grow to nearly 6 feet. This size constraint exists because skin surface area increases more slowly than body volume as animals grow larger, creating an insurmountable oxygen deficit beyond a certain size.

Metabolic studies reveal that lungless salamanders have evolved remarkably low metabolic rates compared to other amphibians. During periods of environmental stress or low oxygen availability, they can reduce their metabolism by up to 80% of normal levels. Rather than switching to anaerobic respiration like many animals do during oxygen shortage, plethodontids simply slow down all biological processes until conditions improve.

Activity levels in lungless salamanders remain consistently low compared to their lung-breathing relatives. Research indicates that most species spend over 90% of their time completely motionless, moving only to feed or escape predators. Sustained activity quickly depletes oxygen reserves that their skin-breathing system cannot rapidly replenish. A lungless salamander fleeing from a predator for just 30 seconds might need several minutes of rest to recover.

Geographic distribution is perhaps the most significant constraint. Lungless salamanders cannot survive in arid environments where their skin would dry out, nor in warm stagnant waters with low oxygen content. They're restricted to consistently humid environments with adequate oxygen availability, explaining why the vast majority of species inhabit temperate forests, mountain streams, and cave systems where humidity remains high year-round.

Despite their physiological constraints, lungless salamanders have achieved remarkable diversity. The Plethodontidae family includes between 516 and 520 species divided among 29 genera, representing the most successful radiation of any salamander group. This diversity often goes unnoticed because many species look superficially similar and occupy cryptic ecological niches.

North America hosts the greatest diversity of lungless salamanders, with particular concentrations in the Appalachian Mountains. This region serves as a biodiversity hotspot where geographic isolation in mountain valleys has driven speciation. Some mountain peaks host endemic species found nowhere else on Earth, with populations separated by just a few valleys evolving into distinct species over millions of years.

The Appalachian Mountains contain more salamander species than anywhere else on Earth, with some mountain peaks hosting species found nowhere else in the world.

The genus Plethodon alone contains 56 species in eastern North America, each adapted to specific elevation ranges, forest types, and moisture regimes. Red-backed salamanders inhabit forest floors from sea level to moderate elevations. Peaks of Otter salamanders live only above 1,200 meters on a few Virginia mountaintops. Shenandoah salamanders occupy talus slopes where they navigate deep rock crevices that maintain stable humidity even during droughts.

Beyond North America, two genera have colonized the Eastern Hemisphere. The European cave salamanders (Speleomantes) inhabit limestone caves and rocky outcrops from France to Sardinia. The Korean crevice salamander (Karsenia koreana), discovered only in 2005, represents an ancient lineage that somehow crossed from North America to Asia, though the details of this remarkable biogeographic journey remain mysterious.

Recent molecular research has uncovered sophisticated biochemical adaptations that make skin breathing possible. Scientists discovered that lungless salamanders express a unique paralogue of the SFTPC gene, typically associated with lung surfactant production in other vertebrates. In plethodontids, this gene produces surfactant-like secretions in the mouth lining and skin that may reduce surface tension and facilitate gas exchange.

The buccopharyngeal cavity, the moist interior of the mouth and throat, serves as a secondary respiratory surface. Lungless salamanders actively pump their throat in a process called buccal pumping, moving air or water across these vascularized tissues. While this provides only 7-17% of total oxygen uptake, it becomes critically important during periods of high activity or environmental stress when skin respiration alone cannot meet metabolic demands.

Hemoglobin adaptations further enhance oxygen uptake efficiency. Lungless salamanders possess hemoglobin variants with exceptionally high oxygen affinity, allowing them to extract oxygen from environments where other vertebrates would suffocate. Their blood also contains higher concentrations of red blood cells than most amphibians, maximizing oxygen-carrying capacity despite the limitations of cutaneous respiration.

Perhaps most remarkably, some species can absorb oxygen directly through their stomach lining when swallowing air bubbles or oxygenated water. This auxiliary respiratory surface provides emergency oxygen during extreme situations, though it contributes minimally to regular respiration. The evolution of multiple redundant gas exchange surfaces demonstrates the extreme selective pressure to maximize oxygen uptake in the absence of lungs.

The very adaptations that allowed lungless salamanders to thrive for millions of years now make them acutely vulnerable to anthropogenic environmental changes. Climate research indicates that rising temperatures pose an existential threat to these cold-adapted specialists. Every 1°C increase in stream temperature reduces dissolved oxygen by approximately 2% while increasing salamander metabolic rates by 10%, creating an escalating mismatch between oxygen supply and demand.

Recent studies in the Appalachian Mountains found that lungless salamander populations have already shifted their ranges upward by an average of 30 meters in elevation per decade, tracking cooling temperatures up mountainsides. Species already inhabiting mountain peaks have nowhere left to go, facing potential extinction as their habitat warms beyond survivable limits.

"We're seeing salamander populations disappearing from lower elevations where they were common just 20 years ago. They're literally running out of mountain."

- Dr. Michael Jenkins, Conservation Biology Institute

Water pollution presents another critical threat. The permeable skin that allows gas exchange also readily absorbs toxins, pesticides, and heavy metals from the environment. Agricultural runoff containing nitrates and phosphates triggers algal blooms that deplete oxygen levels in streams. Acid rain, particularly problematic in eastern North America, alters skin pH and disrupts the delicate chemistry required for cutaneous respiration.

Emerging infectious diseases, particularly the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, attack the very skin salamanders depend on for breathing. This pathogen thickens the skin and disrupts electrolyte balance, essentially suffocating infected individuals. While some populations show resistance, others have experienced complete local extinctions within months of pathogen arrival.

Habitat fragmentation compounds these threats by isolating populations and preventing genetic exchange. Many lungless salamander species have limited dispersal abilities, rarely traveling more than a few hundred meters from their birth sites. Road construction, deforestation, and stream modification can permanently separate populations, reducing genetic diversity and resilience to environmental stressors.

Lungless salamanders challenge our fundamental assumptions about animal physiology. Their success demonstrates that even seemingly essential organs like lungs can become obsolete given the right environmental conditions and evolutionary pressures. These remarkable amphibians prove that life finds ways to thrive through radically different solutions to universal challenges.

From a biomimicry perspective, understanding cutaneous respiration could inspire novel technologies for gas exchange in medical devices or underwater breathing apparatus. The surfactant secretions that facilitate skin breathing might inform development of new materials for enhanced gas permeability. The salamanders' ability to dramatically reduce metabolism during oxygen limitation could provide insights for preserving human tissues during surgery or treating conditions involving oxygen deprivation.

The evolutionary history of lungless salamanders also illuminates how major evolutionary transitions occur. The loss of lungs didn't happen overnight but through gradual reduction over millions of years, with each intermediate stage remaining viable. This exemplifies how evolution doesn't always add complexity, sometimes the path forward involves strategic simplification and loss of seemingly vital structures.

For conservation biology, lungless salamanders serve as sentinels of ecosystem health. Their extreme sensitivity to temperature, moisture, and water quality makes them early warning systems for environmental degradation. Healthy populations of lungless salamanders indicate pristine stream conditions and intact forest ecosystems. Their decline signals problems that will eventually affect more resilient species.

Looking ahead, the fate of lungless salamanders hangs in precarious balance. Climate models predict that suitable habitat for many species could shrink by 70% or more by 2080. Some researchers advocate for assisted migration, moving populations to higher elevations or latitudes before their current habitat becomes uninhabitable. Others focus on protecting climate refugia, areas predicted to remain suitable despite broader warming trends.

Captive breeding programs have begun for several critically endangered species, though maintaining proper humidity and temperature conditions for skin breathing presents unique challenges. Some facilities use sophisticated misting systems and climate control to replicate mountain stream conditions, but success remains limited compared to programs for other amphibians.

Emerging research offers some hope. Scientists recently discovered that certain populations show genetic adaptations for tolerating warmer temperatures and lower oxygen levels. By identifying and protecting these resilient populations, we might preserve genetic variation crucial for species survival. Gene banking efforts now store tissue samples from diverse populations, creating an biological insurance policy against extinction.

Habitat restoration projects focusing on stream buffers and canopy cover show promise for maintaining cool, moist microclimates. Removing dams and restoring natural stream flow patterns can enhance oxygen levels and create the turbulent water conditions lungless salamanders prefer. Even small interventions like installing woody debris in streams can create the complex habitat structures these amphibians require.

The story of lungless salamanders ultimately reflects the broader narrative of evolution's creativity and fragility. These remarkable creatures achieved something that seems impossible, thriving for millions of years without the lungs that most of us consider essential for terrestrial life. Their success across hundreds of species and diverse habitats demonstrates that nature's solutions often defy our expectations.

Yet their exquisite adaptations, honed over evolutionary time scales, now represent vulnerabilities in our rapidly changing world. The same permeable skin that allows them to breathe makes them vulnerable to pollution. The cold mountain streams they depend on are warming. The humid forests that shelter them face increasing drought and fragmentation.

Every lungless salamander is a living testament to evolution's ingenuity - an animal that solved the challenge of breathing without lungs through millions of years of refinement.

Understanding and protecting lungless salamanders isn't just about preserving obscure amphibians that most people will never see. These species maintain ecosystem balance by controlling invertebrate populations and serving as prey for larger animals. They cycle nutrients between aquatic and terrestrial environments. Their presence indicates healthy watersheds that provide clean drinking water for human communities downstream.

As we face an uncertain environmental future, lungless salamanders remind us that life's solutions are often more ingenious and precarious than we imagine. Their continued survival depends on our willingness to protect the specific conditions they need: cold, clean water, intact forests, and connected habitats. In preserving these remarkable skin breathers, we preserve not just a biological oddity but a testament to evolution's boundless creativity and a critical component of some of Earth's most biodiverse ecosystems.

The next time you encounter a small salamander in a mountain stream or forest, take a moment to appreciate the physiological marvel before you. That tiny amphibian, breathing through its skin in defiance of vertebrate conventions, represents one of nature's most audacious experiments in the art of staying alive. Whether these extraordinary creatures continue to grace our planet's streams and forests will depend largely on the choices we make in the coming decades about climate, conservation, and our relationship with the natural world.

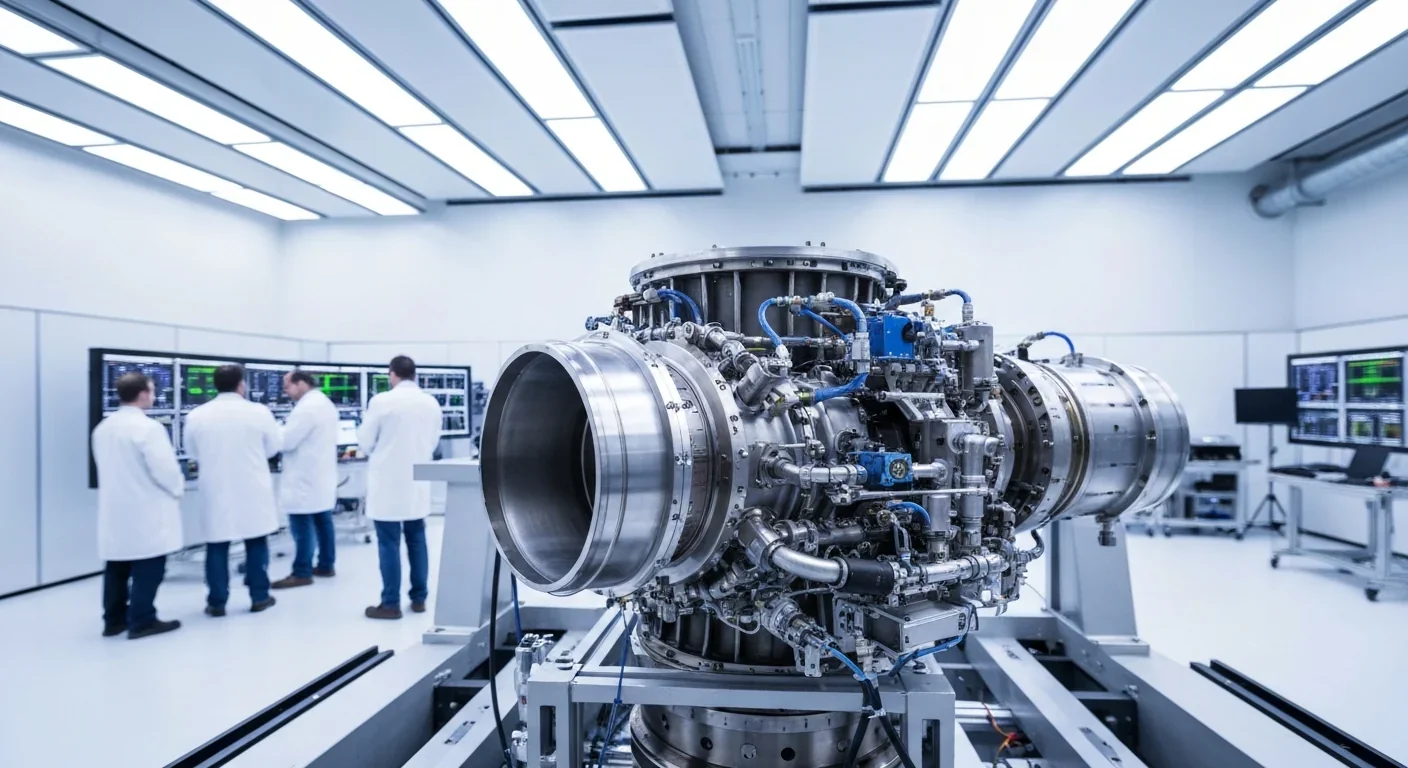

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

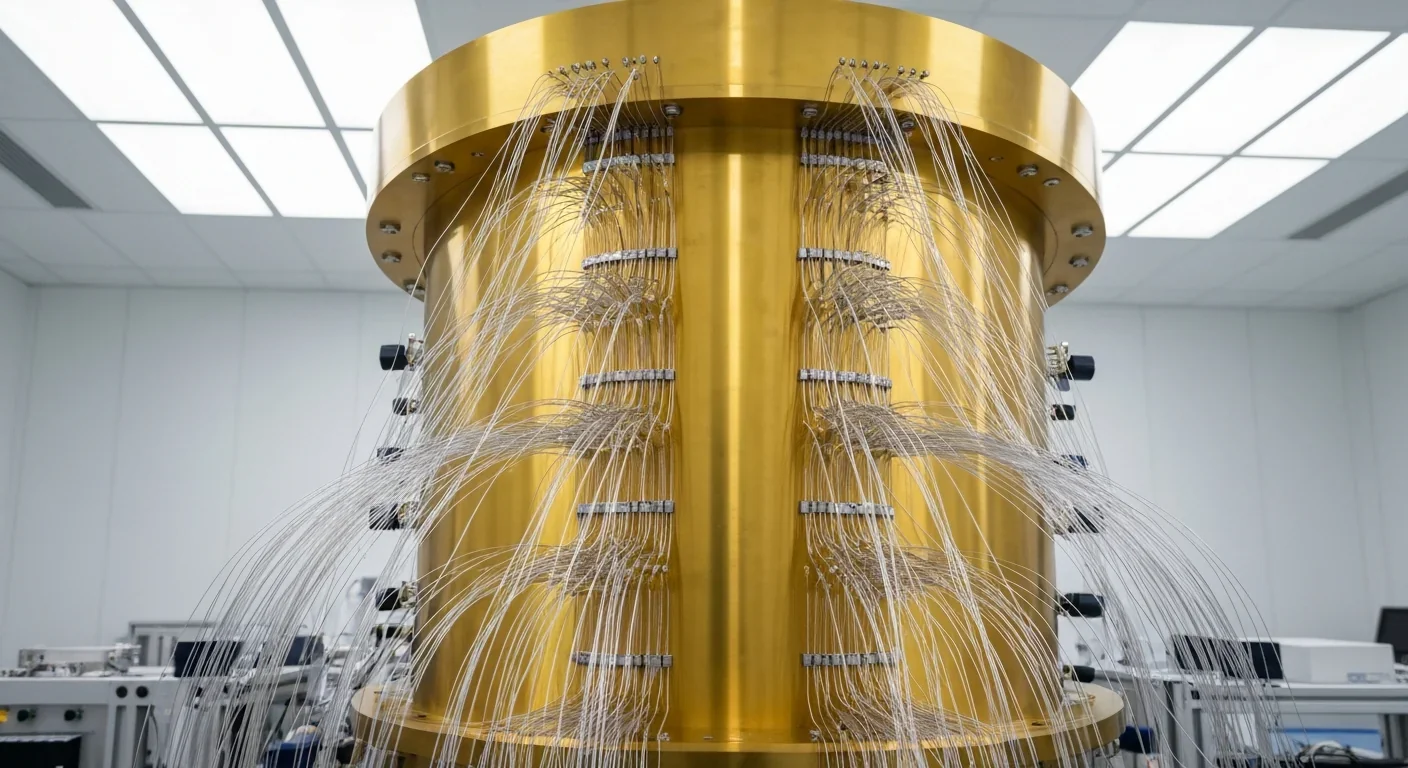

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.