Nature's First Farmers: 50 Million Years of Ant Agriculture

TL;DR: In India's Meghalaya region, indigenous Khasi and Jaintia communities grow living bridges from rubber fig tree roots that last centuries and strengthen over time. These bioengineered structures offer climate-resilient infrastructure lessons for modern architecture.

What if bridges could heal themselves, grow stronger with age, and fight climate change - all while carrying dozens of people? In Northeast India's Meghalaya state, that's exactly what's happening. For centuries, the Khasi and Jaintia communities have been cultivating living root bridges from rubber fig trees, creating infrastructure that defies everything modern engineering tells us about how structures should work.

These aren't bridges in the conventional sense. They're living organisms, carefully guided by human hands over decades, that become more resilient with every passing year. While steel corrodes and concrete crumbles under Meghalaya's relentless monsoons - the region receives some of the heaviest rainfall on Earth - these bridges just keep growing, adapting, strengthening.

The process begins simply enough: plant a rubber fig tree (Ficus elastica) near a riverbank. But what happens next represents a sophisticated understanding of plant biology that predates modern sustainability movements by centuries.

The Khasi people guide the tree's aerial roots - those dangling, snake-like appendages that hang from the branches - across rivers and ravines using bamboo or betel nut trunk scaffolds. These hollow guides become living conduits, directing root growth exactly where it needs to go. The roots follow the scaffolding across gaps that would be impossible to bridge with conventional materials, anchoring themselves to rocks and soil on the opposite bank.

Here's where it gets fascinating: the roots don't just sit next to each other. They fuse together through a natural process called inosculation, where living plant tissues graft into a single, unified structure. According to research published in Nature by a team from the Technical University of Munich, this grafting provides two critical engineering functions: structural redundancy and distributed load bearing.

The fused roots create multiple load paths, so if one section weakens, others compensate. It's a biological backup system that no static bridge can match.

"From a structural perspective, the inosculations provide two functions," explains Wilfrid Middleton, an architect at TUM who helped map 74 living bridges across the region. The fused roots create multiple load paths, so if one section weakens, others compensate. It's a biological backup system that no static bridge can match.

The construction timeline requires patience that modern society has largely forgotten. A bridge takes 15 to 30 years before it can safely support foot traffic. But here's the payoff: once functional, these bridges can last for centuries. Some are estimated to be over 500 years old and can hold up to 50 people simultaneously.

Meghalaya presents one of the harshest environments for infrastructure on the planet. The state's name translates to "abode of clouds," and it's not hyperbole. Cherrapunji and Mawsynram, both in Meghalaya, regularly compete for the title of wettest place on Earth, receiving over 11,000 millimeters of annual rainfall.

In 2011, a particularly fierce monsoon hit the village where artisan Hally War had spent 50 years cultivating his bridge. The storm destroyed an adjacent bamboo crossing, washing it downstream in hours. War's living root bridge stood firm, surviving without significant damage. That single event encapsulates why these structures matter.

"The bridge stood, surviving the calamity without significant damage."

- Witness account, 2011 monsoon

Traditional materials degrade rapidly in Meghalaya's climate. Wood rots. Steel corrodes. Concrete weakens as water seeps into micro-cracks and freezes during winter months. Even modern composite materials require constant maintenance and eventual replacement.

Living root bridges take the opposite approach. Rather than resisting the environment, they work with it. The trees that produce them thrive in moisture. The aerial roots actually benefit from humidity, growing faster and stronger. Where conventional bridges weaken over time, root bridges gain tensile strength as more roots interweave and fuse.

The environmental advantages extend beyond durability. These bridges actively stabilize soil and prevent erosion along riverbanks. Their root systems filter runoff, improving water quality. They provide habitat for insects, birds, and small mammals, creating wildlife corridors across otherwise fragmented landscapes. And unlike their conventional counterparts, they sequester carbon rather than producing it during construction.

Root training isn't something you can learn from a manual. It's intergenerational knowledge, passed down through oral tradition and hands-on practice. The techniques are deceptively simple but require deep understanding of plant behavior, local ecology, and community coordination.

Daily maintenance is crucial. Locals don't just build these bridges and walk away. They tie new roots into existing structures, prune back wayward growth, and continuously shape the living architecture. It's a relationship, not a construction project.

The construction process itself is often a communal effort, involving entire villages. This isn't just practical - it's culturally significant. The bridges become symbols of collective achievement, linking generations through shared purpose. When a grandfather guides young roots across a river, he knows he may never walk on the completed bridge. But his children will. And their children.

Hally War spent half a century establishing the first deck of his bridge. For the last 17 years, he's been working on a second level above it. The famous Umshiang Double-Decker Bridge in Nongriat village, one of the region's most photographed structures, took over a century to reach its current form. It's a testament to patience, vision, and the willingness to create something that transcends a single human lifespan.

"It took me 50 years of work to establish the first stage, and for the last 17 years I have also been working on a second deck."

- Hally War, bridge artisan

Cultural taboos and rituals also play important roles. In some communities, only elders can plant the initial tree. The belief is that a young person planting a tree destined to outlive them by centuries would somehow transfer their vital energy to the plant. Whether or not you believe in such practices, they serve a practical purpose: ensuring that planting is done thoughtfully, by people with deep knowledge of the land.

For years, living root bridges were largely unknown outside Meghalaya. That changed when researchers from the Technical University of Munich published comprehensive documentation in Nature, examining and mapping 74 different bridges across the region.

The research revealed something remarkable: these structures demonstrate engineering principles that biomimicry experts are only now beginning to understand. The bridges exhibit tensile strength comparable to modern suspension bridges, but achieved through organic growth rather than industrial manufacturing. They distribute loads dynamically, adjusting to stress in real-time as living tissue responds to pressure.

The study also highlighted how different each bridge is. Unlike standardized infrastructure, every root bridge is unique - adapted to its specific location, shaped by the people who tend it, and continuously evolving. Some span just a few meters. Others stretch over 30 meters across deep gorges.

This research has sparked interest among architects and engineers worldwide. Can we apply these principles to modern infrastructure? The question isn't about growing bridges everywhere - that's impractical in most climates - but about understanding the underlying concepts: structures that self-repair, grow stronger with age, adapt to environmental stress, and integrate with rather than dominate ecosystems.

Several biomimicry projects are now exploring living architecture. In Utrecht, Netherlands, researchers are experimenting with guiding willow growth to create structures. German designers are developing frameworks that help trees grow into specific shapes. None have achieved the longevity and functionality of Meghalaya's root bridges, but they're learning.

Here's the problem: the knowledge required to build these bridges is fading. Younger generations are leaving villages for cities. The time investment - decades before a bridge becomes functional - discourages new projects. UNESCO received a nomination in 2022 for 72 bridges to receive World Heritage status, but recognition alone won't preserve the practice.

A steel bridge will need replacement in 30-40 years. A root bridge, if maintained, can function for centuries while actually improving over time.

Patrick Rogers, a researcher who has studied the bridges extensively, warns that "the art of weaving and preserving the living root bridges is slowly fading away." The challenge is partly practical - it takes an extremely long time for bridges to become functional and safe to use. But it's also cultural. Modern materials offer quick solutions. Why wait 20 years when you can build a steel bridge in months?

The answer lies in long-term thinking. That steel bridge will need replacement in 30-40 years. The root bridge, if maintained, can function for centuries while actually improving over time. But convincing communities to invest in multi-generational infrastructure requires a shift in perspective that runs counter to contemporary development pressures.

Some encouraging signs exist. Tourism has increased awareness and generated income for communities that maintain bridges. Mawlynnong village, known as one of Asia's cleanest villages, has leveraged its root bridge to attract visitors who contribute to the local economy. The famous Double-Decker Bridge in Nongriat draws photographers and adventurers from around the world.

But tourism brings its own challenges. Increased foot traffic accelerates wear. Commercial pressures can conflict with traditional maintenance practices. The bridges weren't designed for Instagram - they're working infrastructure for rural communities.

What can living root bridges teach us about building for the future? Several lessons stand out:

Infrastructure doesn't have to fight nature. The conventional approach treats the environment as an adversary to overcome. Root bridges demonstrate that working with ecological processes can produce more resilient results. In an era of increasing climate volatility, infrastructure that adapts rather than resists may prove more durable.

Time horizons matter. Modern development operates on timescales measured in electoral cycles and fiscal quarters. Root bridges remind us that some problems require multi-generational thinking. Climate-resilient infrastructure won't materialize overnight, but investments made today can yield benefits for centuries.

Local knowledge has value beyond preservation. These techniques aren't museum pieces - they're functional engineering solutions developed through centuries of observation and experimentation. Dismissing them as "primitive" misses their sophistication. Indigenous knowledge systems often contain insights that Western science is only beginning to understand.

Maintenance culture matters as much as construction. Root bridges don't survive because they're built well - they survive because communities care for them continuously. Modern infrastructure often fails not from design flaws but from deferred maintenance. The daily attention Khasi communities give their bridges could inform how we think about long-term infrastructure stewardship.

Resilience comes from redundancy. The inosculated roots create multiple load paths. If one fails, others compensate. This biological redundancy offers a template for designing systems that degrade gracefully rather than failing catastrophically - relevant for everything from bridges to power grids to supply chains.

The principles underlying living root bridges are increasingly influencing contemporary design. Biomimicry - learning from and mimicking natural processes - has moved from fringe concept to mainstream consideration in architecture and engineering.

Self-healing concrete, inspired by how bones repair micro-fractures, is now commercially available. It incorporates bacteria that produce limestone when exposed to water, automatically sealing cracks. The concept mirrors how root bridges continuously grow new tissue to repair damage.

Adaptive façade systems mimic how plants open and close stomata to regulate temperature and moisture. These building skins respond to environmental conditions in real-time, reducing energy consumption while improving comfort. It's the same principle that allows root bridges to adjust their structure based on load and weather conditions.

Mycelium-based building materials - grown rather than manufactured - are emerging as sustainable alternatives to foam insulation and packaging materials. Like root bridges, they represent infrastructure grown from living organisms rather than extracted, refined, and assembled from industrial processes.

None of these innovations directly replicate living root bridges, but they share a philosophical approach: what if infrastructure could be alive? What if our built environment could grow, adapt, heal, and integrate with natural systems rather than replacing them?

The future of living root bridges sits at the intersection of preservation, innovation, and cultural survival. Several pathways forward are emerging:

Documentation and knowledge transfer are critical. Researchers are working with communities to record techniques in detail, creating resources that future generations can reference. Video documentation captures nuances that written descriptions miss.

Economic models that value patience could help. If communities receive sustained funding tied to bridge maintenance rather than one-time construction payments, the economics might favor traditional methods. Carbon credit programs could compensate communities for the sequestration these living structures provide.

Hybrid approaches might bridge tradition and modernity. Some engineers are experimenting with initial steel frameworks that living roots eventually replace, reducing the time before structures become functional while retaining long-term benefits.

Educational initiatives could spread knowledge beyond Meghalaya. Teaching biomimicry principles in architecture and engineering schools, using root bridges as case studies, ensures that even if the practice itself contracts, the underlying insights inform future design.

The fundamental challenge is time. Living root bridges demand timescales that modern society finds uncomfortable. We want solutions now, not in 20 years. But some problems - climate change chief among them - require exactly that kind of long-term thinking.

On a humid morning in Nongriat village, sunlight filters through the canopy onto the Double-Decker Root Bridge. Tourists pause to take photos. Local residents cross on their way to tend fields. Children play on the sturdy deck, their laughter echoing off the surrounding forest.

The bridge their great-great-grandparents began is still growing. Roots that were thin as rope a century ago are now thick as tree trunks, fused into a lattice that could support a small truck. New tendrils are already being guided to strengthen weak points and extend the span.

This is infrastructure as living practice - never finished, never perfect, always evolving. It's a radical departure from the build-it-and-forget-it mentality that dominates modern construction. And in a world facing unprecedented environmental challenges, it might be exactly the model we need.

The question isn't whether we can replicate these bridges everywhere. We can't. Most climates don't support the species involved, and few communities possess the knowledge required. But we can learn the deeper lesson: what if we designed infrastructure to last not years or decades but centuries? What if we built things that improved with age rather than deteriorated? What if our structures gave back to the environment rather than extracted from it?

The Khasi and Jaintia people have been answering these questions for centuries. Their living root bridges aren't just engineering marvels or cultural treasures. They're proof that another way is possible - infrastructure that works with nature, strengthens communities, and leaves the world better than it found it.

As climate change forces us to rethink how we build and live, these bridges offer more than metaphor. They're a living demonstration that patience, knowledge, and respect for natural processes can create solutions that outlast any structure we could force into existence. The real question is whether we're willing to think on the timescale required to build them.

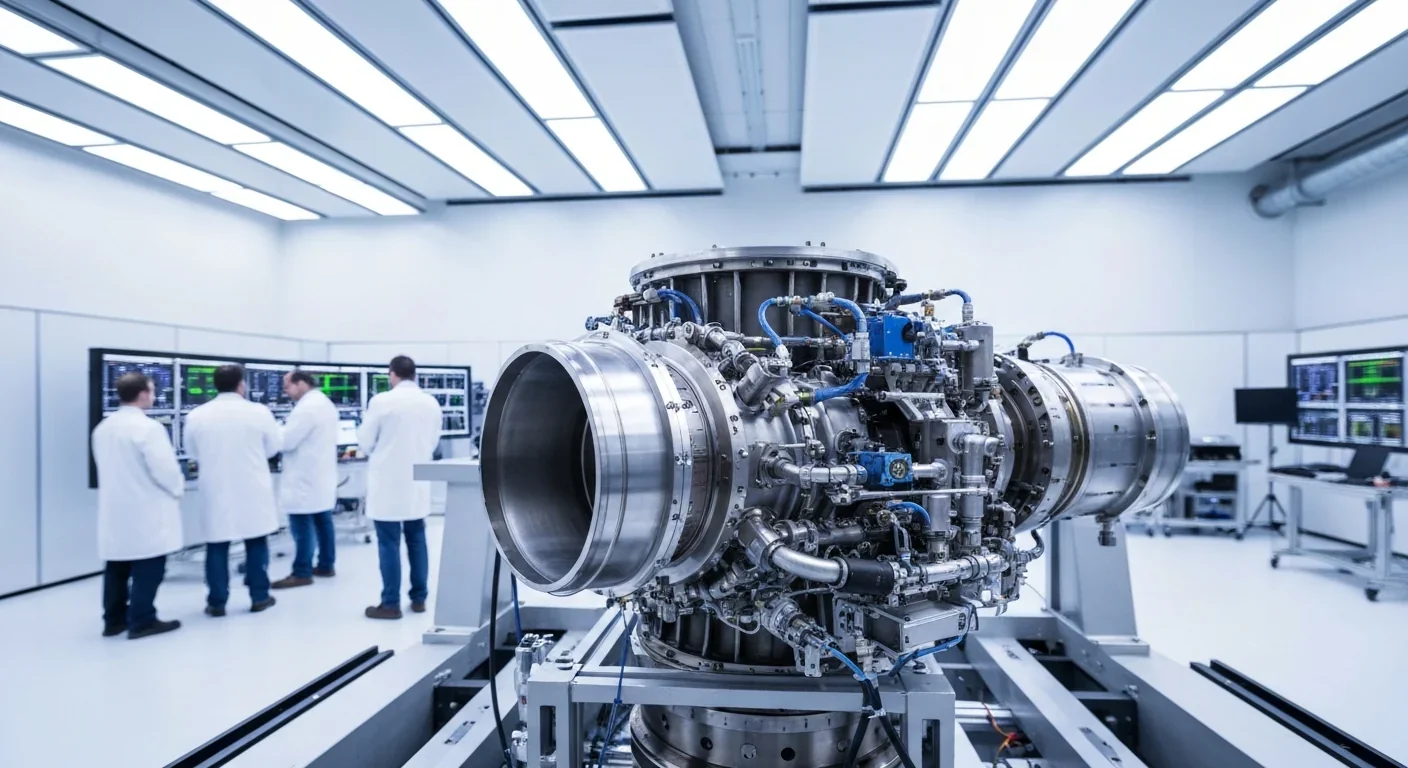

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

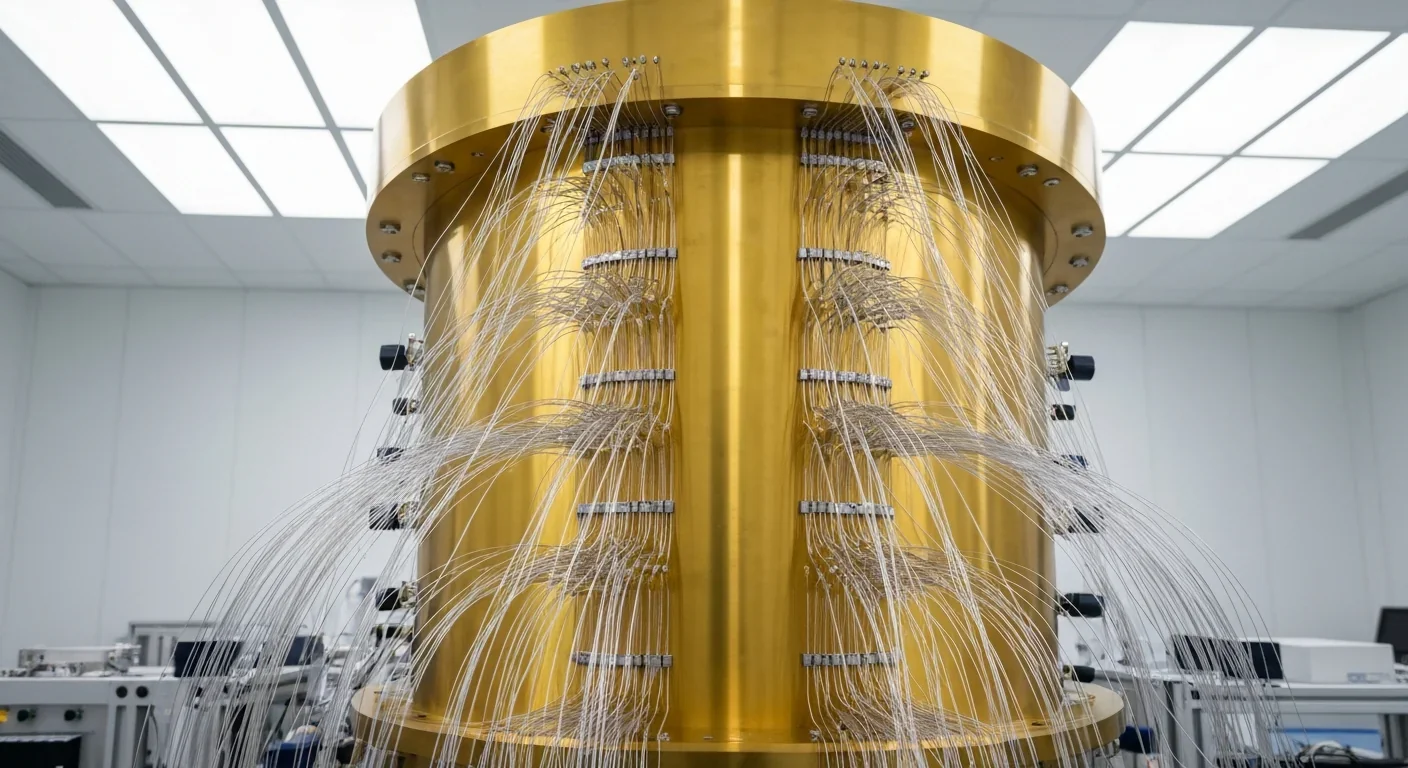

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.