Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Kleptoparasitism - systematically stealing food from other animals - is a sophisticated survival strategy used by species from frigatebirds to hyenas. These master thieves have evolved specialized physical and behavioral adaptations for piracy, creating evolutionary arms races with their victims and reshaping entire ecosystems through resource redistribution and disease transmission.

Imagine spending hours hunting for food, only to have it snatched away at the last second by a brazen pirate. In the animal kingdom, this isn't just bad luck - it's an entire survival strategy. Kleptoparasitism, the systematic theft of food or resources from other animals, represents one of nature's most cunning adaptations. From frigatebirds that harass their victims mid-flight to hyenas that intimidate lions away from fresh kills, these specialized thieves have evolved remarkable tactics that challenge our simple understanding of predators and prey.

The strategy is surprisingly widespread. Skuas shake gulls violently until they vomit up their catch. Frigatebirds chase boobies across tropical skies, forcing them to regurgitate fish. Even spiders sneak into other spiders' webs to steal their meals. What makes these animals successful isn't just opportunism - it's a suite of specialized adaptations honed by millions of years of evolution.

Why steal when you could hunt? The answer lies in a brutal calculus of energy and risk. Hunting requires significant effort: stalking prey, executing attacks, and risking injury or failure. Stealing bypasses all of that. A hyena that steals a cheetah's kill gets the same nutritional reward without the dangerous sprint or exhausting chase.

The math is compelling. A study of great frigatebirds found they could obtain up to 40% of their food needs through theft alone, though the average was closer to 5%. That's still a significant supplement when you consider the energy saved. For some species, the trade-off is even better.

Some frigatebirds obtain up to 40% of their dietary needs through theft, demonstrating that piracy can be as important as hunting for survival in resource-limited environments.

Arctic skuas invest heavily in flight performance specifically for stealing. With wingspans reaching 125 cm and flight speeds hitting 50 kph, these birds are built for aerial piracy. They chase down terns, gulls, and puffins with relentless aggression, forcing their victims to drop freshly caught fish. The energy spent chasing is far less than the energy required for diving and fishing themselves.

But theft isn't free. Victims don't surrender their hard-won meals without resistance. This creates an evolutionary arms race where thieves develop better stealing tactics and victims evolve better defenses. The result is a constantly shifting balance that shapes entire ecosystems.

Not all thieves are equal. Some animals depend almost entirely on stealing - these are obligate kleptoparasites. Others steal opportunistically when chances arise - the facultative kleptoparasites.

Skuas represent the obligate extreme. These powerful seabirds have made kleptoparasitism their primary feeding strategy. The South Polar Skua patrols Antarctic waters specifically to pirate food from other seabirds. Its technique is brutally effective: grab a shearwater or gull with its powerful bill and shake violently until the victim regurgitates its catch. These birds are so dependent on theft that they spend significant portions of their day searching for potential victims rather than hunting for themselves.

Frigatebirds sit in an interesting middle ground. These magnificent fliers possess the largest wing-area-to-body-weight ratio of any bird, allowing them to soar for weeks without landing. While they do catch their own fish and squid by snatching them from the ocean surface, they're equally famous for their piracy tactics. They chase down red-footed boobies, tropicbirds, and terns, harassing them relentlessly until the victims regurgitate their meals.

What's fascinating is that frigatebirds' dependence on theft varies by location and season. In areas where fish are driven to the surface by tuna or where flying fish are abundant, frigatebirds hunt more directly. When those conditions disappear, theft becomes more attractive. This flexibility demonstrates how kleptoparasitism exists on a spectrum rather than as a binary choice.

"Kleptoparasitism makes perfect sense from an energy conserving point of view. The nutritional gain provided by a carcass can be obtained without any risk of being injured during a hunt or the energy expenditure involved in a chase."

- Researchers studying hyena behavior

At the facultative end, we find opportunists like hyenas. Contrary to popular belief, hyenas are excellent hunters. Most of their diet comes from their own kills - they can run at 40-50 km/h over distances up to 24 km, and a single adult can take down a full-grown wildebeest. Yet when a fresh lion kill presents itself, hyenas won't hesitate to mob the larger predators and steal the carcass. It's not their primary strategy, but it's always in their playbook.

Evolution has equipped kleptoparasites with specific tools for their trade. These adaptations reveal how stealing exerts its own selective pressures, distinct from those that shape hunters.

Speed and agility rank among the most crucial traits. The Arctic skua's 50 kph flight speed isn't particularly impressive compared to falcons, but it's perfectly calibrated for overtaking the seabirds it targets. Skuas combine this speed with extraordinary maneuverability, allowing them to match every evasive turn their victims attempt. Their wing structure provides both the acceleration needed for closing distance and the control required for maintaining pursuit through complex aerial chases.

Size and intimidation matter tremendously. The South Polar Skua measures 21 inches with a bulky build, thick neck, and wide wings - a morphology designed for both hunting and aggressive theft. This combination of size and power allows it to physically dominate smaller seabirds. When a skua grabs a gull by the neck and shakes it, there's no contest. The victim's only option is to surrender its meal.

Endurance separates the successful thieves from the failures. Frigatebirds can soar for weeks without landing, their enormous wingspan providing lift without constant flapping. This endurance isn't about catching prey - it's about maintaining pursuit long enough to exhaust victims psychologically. A booby being chased by a frigatebird faces a calculation: keep the fish and endure harassment that might last 20 minutes, or drop it and end the ordeal. Often, the harassment wins.

Some thieves have evolved behavioral rather than physical adaptations. Great skuas employ sophisticated tactics including coordinated attacks where multiple birds work together to overwhelm victims. One skua might attack from above while another approaches from below, dividing the victim's attention and increasing the chance of forced regurgitation.

Evolution doesn't favor only thieves. Victims under constant pressure to defend their food have developed counter-strategies that make theft more difficult and risky.

Speed and evasion represent the first line of defense. Terns, frequent victims of skua piracy, have become remarkably agile fliers. When pursued, they execute rapid turns and altitude changes that force skuas to work harder for each theft attempt. The longer a chase continues, the less energetically favorable it becomes for the thief.

Group defense provides another effective counter. Gulls and other colonial seabirds often mob kleptoparasites, with multiple individuals diving at the attacker. A single skua might successfully steal from a lone gull, but facing five or ten gulls simultaneously changes the equation. The physical risk increases while the probability of success drops.

Some species have evolved to simply avoid thieves. Red-footed boobies that nest in frigatebird colonies often alter their foraging schedules, feeding at times or in locations where frigatebirds are less active. Others have learned to approach nesting areas from unexpected angles, reducing the chance of interception.

The evolutionary arms race between thieves and victims creates a Red Queen dynamic - both sides must constantly evolve just to maintain their current success rates.

Physical defense works for larger victims. When hyenas attempt to steal from lions, they face genuine danger. Lions will kill hyenas that push too hard, creating a risky calculation. Hyenas must judge whether the meal is worth potentially fatal retaliation. Usually, they succeed through numerical superiority - a clan of 10-15 hyenas can intimidate even a pride of lions - but the risk never disappears entirely.

Perhaps the most interesting counter-adaptation is deception. Some seabirds, when pursued, perform fake regurgitation displays without actually giving up their catch. If the thief falls for the ruse and breaks off pursuit to search for the supposedly dropped meal, the victim escapes. This represents a sophisticated cognitive strategy that shows how the arms race between thieves and victims extends beyond physical traits into behavioral complexity.

Kleptoparasitism doesn't exist in isolation. Its effects cascade through ecosystems in ways that reshape entire food webs and even influence disease transmission.

Resource redistribution is one direct consequence. When frigatebirds steal from boobies, they're effectively transferring energy from one trophic pathway to another. Boobies that lose meals must hunt more frequently to compensate, increasing their predation pressure on fish populations. Meanwhile, frigatebirds that supplement their diet through theft can reduce their own direct hunting, potentially benefiting the fish species they would otherwise target.

The impacts become more complex when theft involves multiple species. Skuas don't just steal from one victim type - they target anything carrying food, from small terns to large gulls. This generalist approach means skuas affect the feeding success of numerous seabird species simultaneously, creating competitive disadvantages that might influence breeding success and population dynamics.

Disease transmission adds a darker dimension. Recent research has revealed that kleptoparasitic interactions can facilitate pathogen spread across vast distances. During the 2022 avian influenza outbreak, roughly half the world's great skuas died from HPAI H5N1. The virus spread so effectively because skuas' kleptoparasitic behavior brings them into close contact with numerous other seabird species, creating transmission opportunities that wouldn't exist otherwise.

"Pirate birds force other seabirds to regurgitate fish meals. Their thieving ways could spread lethal avian flu across isolated breeding colonies that span tens of thousands of kilometers."

- The Conversation, on disease transmission via kleptoparasitism

Frigatebirds present an even more concerning vector. These birds travel tens of thousands of kilometers annually, visiting seabird colonies across multiple oceans. When they steal food through forced regurgitation - a behavior that creates aerosols of potentially contaminated fluid - they can transmit diseases between isolated populations that might otherwise never interact. This transforms localized outbreaks into global pandemics affecting dozens of species.

The evolutionary implications extend further. In ecosystems with heavy kleptoparasitism, victims face selection pressure not just to be better hunters but to be better defenders. This dual pressure can drive morphological and behavioral evolution in directions that wouldn't occur in theft-free environments. Seabirds in skua-rich areas tend to be faster and more maneuverable than relatives in skua-free zones, suggesting that the presence of thieves actively shapes victim evolution.

While seabirds dominate the kleptoparasitism literature, the strategy appears throughout the animal kingdom, often in unexpected places.

Among mammals, theft operates at scales from tiny to enormous. Hyenas steal from lions and cheetahs, as mentioned, but they're far from alone. African wild dogs occasionally rob cheetahs. Coyotes steal from badgers. Even bears have been observed driving wolves from kills. Each interaction follows similar economic logic: assess the risk, estimate the reward, and act when the balance favors theft.

In the ocean, theft takes fascinating forms. Some fish species follow larger predators and grab pieces of their prey during feeding frenzies. Remoras attach to sharks and mantas, feeding on scraps. More actively, some wrasses steal food directly from the mouths of other fish, timing their approach to snatch morsels during the split second when a victim's mouth opens.

Insects practice kleptoparasitism with remarkable sophistication. Certain spider species specialize in invading other spiders' webs to steal already-caught prey. They move carefully to avoid detection, plucking the web strands in patterns that mimic trapped insects. When the web's owner investigates, thinking it's dinner time, the thief steals the actual prey. Some of these spiders live permanently in other spiders' webs, essentially running protection rackets.

Bees provide another compelling example. Cuckoo bees lay their eggs in other bees' nests, and their larvae consume the food stores the host bee collected for its own offspring. This brood parasitism represents a form of kleptoparasitism where the theft occurs across generations - the cuckoo bee steals not just food but reproductive investment.

Even within species, theft occurs. Gulls steal from other gulls. Pelicans rob pelicans. Ravens steal from ravens. These intraspecific interactions suggest that kleptoparasitism isn't always about specialized adaptations for stealing from particular victims. Sometimes it's simply about recognizing an opportunity and taking it.

How did kleptoparasitism evolve? The transition from hunter to thief isn't instantaneous - it requires intermediate steps where each provides some advantage.

Most researchers believe kleptoparasitism begins with scavenging. An animal that learns to recognize and approach carcasses gains an energy advantage over pure hunters. From there, the step to stealing fresh kills is relatively small. If approaching a carcass is safe, approaching a competitor with prey becomes the next logical move.

Harassment likely started as simple intimidation. A larger scavenger approaches a smaller one and displays aggression. If the smaller animal flees, abandoning its food, the larger one benefits. Over time, selection favors scavengers better at intimidation and those better at resisting intimidation. The arms race begins.

The progression from passive scavenging to active theft marks a critical threshold. It requires the cognitive capacity to recognize that other animals possess food, to assess the likelihood of successful theft, and to execute coordinated harassment strategies. This level of sophistication appears in relatively few taxa, primarily birds and mammals with large brains and complex social behaviors.

Obligate kleptoparasitism represents the evolutionary extreme. For species to depend entirely on theft, they must achieve success rates high enough to sustain themselves. This requires both exceptional stealing ability and sufficient victim density. Skuas meet these criteria in seabird colonies where thousands of birds fish constantly, providing endless theft opportunities. In environments with lower victim density, obligate kleptoparasitism likely couldn't evolve because theft opportunities would be too scarce.

The evolutionary pressures work in both directions. As thieves improve, victims must adapt or face reduced fitness. But as victims improve their defenses, thieves must evolve better tactics. This Red Queen dynamic - constantly running just to stay in place - drives continuous evolutionary change in both parties. The result is a system in perpetual arms race, with neither side ever fully winning.

Observing kleptoparasitism offers more than academic interest. It provides insights into competition, cooperation, and the nature of ecological relationships that extend beyond simple predator-prey models.

The economic principles underlying theft in nature mirror human behavior in surprising ways. Animals assess risks versus rewards, exactly as humans do when making decisions. They recognize and exploit power imbalances. They form coalitions to increase their effective strength. These aren't uniquely human traits - they're fundamental strategic behaviors that emerge whenever competition for resources creates opportunities for theft.

Understanding kleptoparasitism also matters for conservation. Seabird colonies under pressure from climate change may experience shifts in kleptoparasitic dynamics as fish populations move or crash. If prey becomes scarcer, theft might intensify as hunting success declines, creating additional stress on already struggling populations. Conversely, if kleptoparasites decline due to disease or other factors, victim species might experience reduced harassment, potentially improving their breeding success.

The disease transmission aspect carries clear conservation implications. As global travel and climate change bring previously isolated populations into contact, kleptoparasites that act as disease vectors could facilitate pathogen spread in new ways. Managing these risks requires understanding the behavioral ecology of theft - where and when it occurs, which species interact, and how those interactions create transmission opportunities.

Kleptoparasitism research continues revealing new dimensions of this complex behavior. Advances in tracking technology now allow researchers to follow frigatebirds and skuas across entire ocean basins, mapping their theft attempts and success rates in unprecedented detail. These data are revealing that kleptoparasitism varies far more than previously recognized, with individual birds adopting different strategies based on their age, experience, and local conditions.

Genetic studies are beginning to identify the heritable components of kleptoparasitic behavior. Are some individuals naturally better thieves? Do populations in theft-heavy environments evolve genetic adaptations that improve their stealing or defending abilities? Early evidence suggests yes, but the mechanisms remain unclear.

Climate change adds urgency to this research. As ocean temperatures rise and fish populations shift, the energetic calculus underlying theft decisions will change. Species that currently hunt successfully might find stealing more attractive if prey becomes scarcer or harder to catch. Others might abandon theft if victims become too rare or too difficult to find. These shifts could reshape entire food webs in ways we're only beginning to anticipate.

The cognitive dimensions of kleptoparasitism deserve more attention. How do thieves assess victim vulnerability? Can they remember which individuals are easy marks? Do victims learn to recognize particularly skilled thieves and take extra precautions? Evidence suggests complex cognitive processes underlie these interactions, but researchers have barely scratched the surface.

Perhaps most intriguingly, kleptoparasitism forces us to reconsider how we categorize ecological relationships. We typically think in terms of predators, prey, competitors, and cooperators. Kleptoparasites don't fit neatly into any category. They're not true predators because they don't kill their victims. They're not classic competitors because they don't compete for the same resources - they compete for what others have already obtained. They occupy a unique ecological niche that challenges our tidy taxonomies and reminds us that nature's complexity exceeds our frameworks.

Nature's master thieves teach us that survival isn't just about strength, speed, or hunting prowess. Sometimes it's about recognizing an opportunity and seizing it, quite literally. In doing so, these remarkable animals reveal that the line between predator and parasite, hunter and thief, is far blurrier than we imagined. The next time you see a gull harassing another bird, remember: you're watching millions of years of evolutionary refinement in action, a strategy as sophisticated as any predator's stalk, and considerably more brazen.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

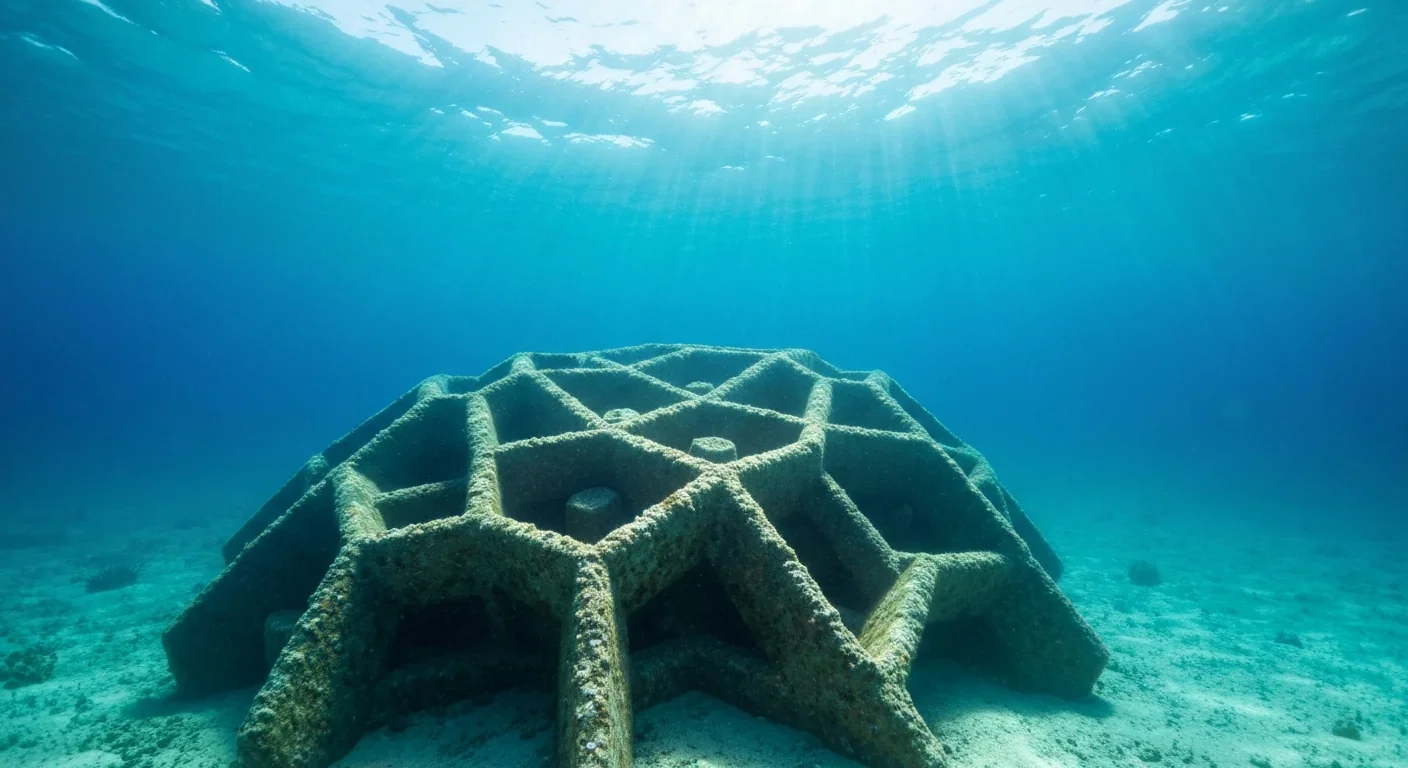

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

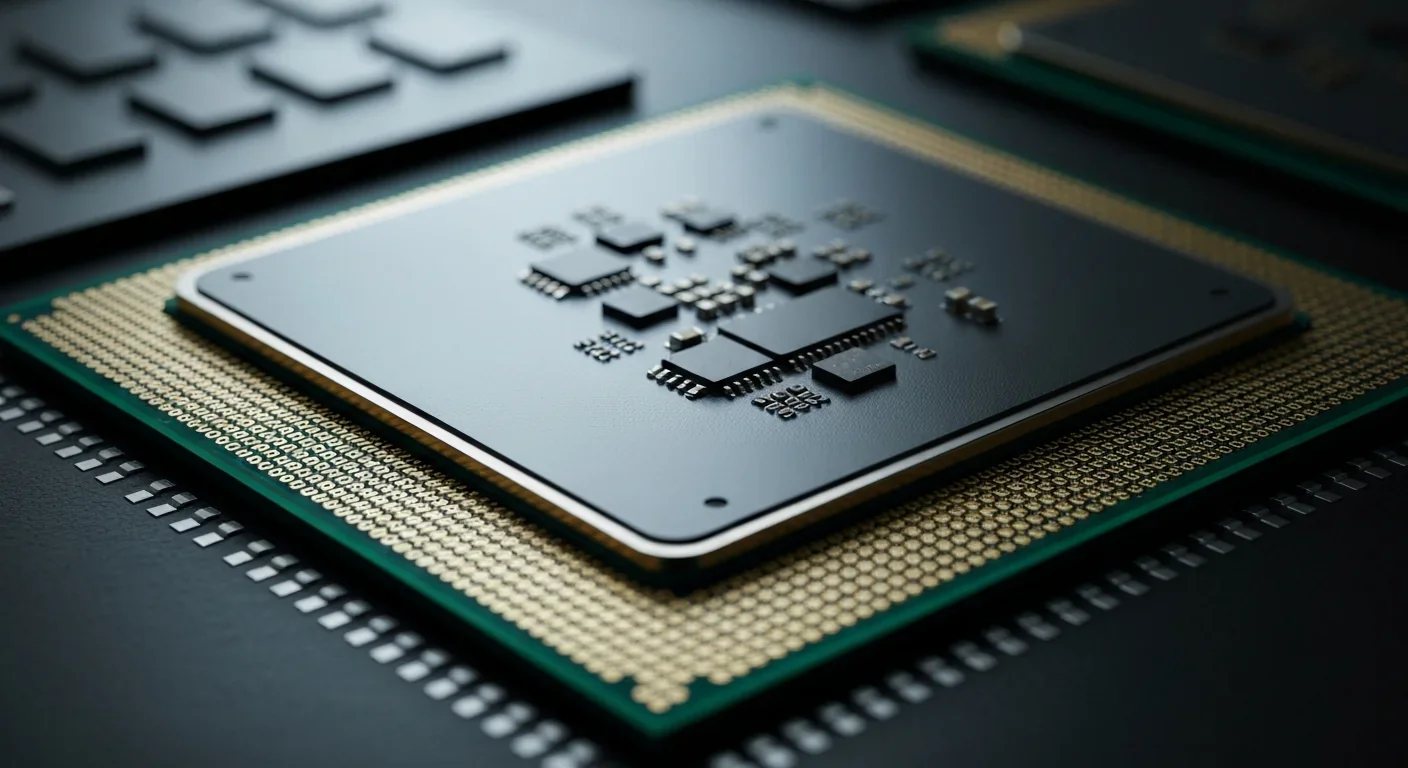

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.