Nature's First Farmers: 50 Million Years of Ant Agriculture

TL;DR: Invasive plants use allelopathy to release toxic chemicals that suppress native species, with garlic mustard reducing mycorrhizal fungi by 60% and Tree-of-Heaven affecting soil 50 feet away. Scientists are developing counterstrategies using biological controls and smart restoration techniques.

Picture a forest floor where native wildflowers once bloomed in abundance, now replaced by a single species spreading like a green carpet. This transformation isn't happening through brute force or faster growth alone. Instead, it's the result of an invisible chemical war being waged beneath our feet, where invasive plants deploy toxic compounds as biological weapons to eliminate their competition.

The weapon of choice? Allelopathy - the release of biochemical compounds that suppress or kill neighboring plants. While this chemical warfare strategy exists throughout the plant kingdom, invasive species have weaponized it with devastating effectiveness, using these toxins to dominate ecosystems they've never encountered before. This silent invasion is transforming landscapes across North America and reshaping our understanding of how plants compete for survival.

At the molecular level, allelopathic plants produce an array of chemical compounds that function as natural herbicides. These chemicals include phenolic acids, alkaloids, terpenoids, and glucosinolates - each targeting different biological processes in competing plants. When released into the soil through root exudates, leaf litter decomposition, or volatile emissions, these compounds interfere with seed germination, root development, nutrient uptake, and photosynthesis in neighboring plants.

The mechanisms of allelopathic suppression are surprisingly sophisticated. Garlic mustard, one of North America's most notorious invaders, releases glucosinolates that break down into toxic isothiocyanates in the soil. These compounds don't just poison other plants directly; they disrupt the mycorrhizal fungi that native plants depend on for nutrient absorption. Studies reveal that garlic mustard can reduce mycorrhizal colonization by up to 60%, essentially starving native species like sugar maple seedlings of essential phosphorus.

"Garlic mustard's roots and decaying leaves provide another advantage by secreting an allelopathic phytotoxin which harms seed germination and many types of mycorrhizal fungi, thereby reducing competition around itself."

- Heritage Conservancy Research

What makes these chemical weapons particularly insidious is their persistence in the environment. Unlike physical competition that ends when a plant is removed, allelopathic chemicals can remain active in soil for years. Seeds from garlic mustard can remain viable for up to twelve years, continuously releasing toxins as they slowly decompose. This creates what ecologists call a "legacy effect" - a chemical shadow that haunts the soil long after the invader itself has been removed.

The concentration and potency of these chemicals vary with environmental conditions. Research shows that allelopathic effects intensify under stress conditions like drought or poor soil quality, giving invaders an even greater advantage when native plants are already struggling. Temperature, soil pH, and microbial activity all influence how these chemicals break down and interact with their targets, creating a complex battlefield where chemical weapons effectiveness shifts with changing conditions.

Among the rogues' gallery of allelopathic invaders, several species stand out for their devastating impacts on native ecosystems. These plants have perfected the art of chemical warfare, each employing unique strategies to dominate their invaded ranges.

Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) has earned its reputation as one of North America's most destructive invasive plants through its dual assault on native flora. Originally introduced from Europe as a culinary herb in the 1860s, it now infests forests from Canada to Georgia. Beyond its direct allelopathic effects, garlic mustard's chemicals specifically target the mycorrhizal networks that connect forest plants, disrupting nutrient sharing and communication systems that have evolved over millennia. A single plant can produce thousands of seeds, each one a potential chemical bomb waiting to germinate.

Female Tree-of-Heaven trees can produce over 300,000 wind-dispersed seeds annually, with root systems extending up to 50 feet from the trunk, continuously releasing toxins that persist in soil for years.

Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) demonstrates the power of allelopathy at a larger scale. This fast-growing tree produces chemicals that inhibit the germination of most native plants, creating barren zones around mature specimens. Female trees can produce over 300,000 wind-dispersed seeds annually, each carrying the genetic instructions for chemical warfare. The tree's root system extends up to 50 feet from the trunk, continuously releasing toxins that can persist in soil for years. Even more concerning, when cut down, Tree-of-Heaven responds by sending up numerous root sprouts, each one continuing the chemical assault on surrounding vegetation.

Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea stoebe) employs a particularly devious strategy. This European invader releases catechin, a compound that triggers oxidative stress in the roots of native North American plants while having minimal effect on European species that evolved alongside it. This selective toxicity exemplifies the "novel weapons hypothesis" - the idea that invasive plants succeed because native species have no evolutionary experience with their particular chemical weapons. In Montana alone, spotted knapweed has invaded millions of acres of rangeland, reducing forage for wildlife and livestock by up to 90%.

Japanese Knotweed (Fallopia japonica), while less studied for its allelopathic properties, demonstrates similar patterns of dominance through chemical suppression. Its extensive rhizome system not only physically dominates underground space but also releases compounds that inhibit the growth of neighboring plants. The plant's ability to regrow from fragments as small as 0.7 grams makes it nearly impossible to eradicate once established.

The success of allelopathic invaders isn't just about the chemicals they produce - it's about the evolutionary naivety of their victims. The novel weapons hypothesis provides a compelling framework for understanding why these chemical weapons are so devastatingly effective in invaded ranges.

In their native habitats, allelopathic plants face competitors that have evolved defenses against their toxins over thousands of years of coevolution. These defenses might include enzymes that break down the chemicals, modified metabolic pathways that avoid disruption, or behavioral adaptations like altered root growth patterns. However, when these plants invade new territories, they encounter species with no such evolutionary preparation.

Native North American plants, for instance, never experienced the specific glucosinolates produced by garlic mustard during their evolutionary history. Without selection pressure to develop resistance, they remain vulnerable to these novel compounds. It's analogous to introducing a new disease to a population with no immunity - the results can be catastrophic.

"Some plants evolve chemical defenses to compete in their original range. In their introduced range, the native species are highly vulnerable to these chemicals because they have no prior experience with them."

- Novel Weapons Hypothesis, Enemy Release Theory

Research comparing invaded and native ranges supports this hypothesis. A meta-analysis of 15 exotic plant studies found that invasive plants faced fewer herbivores and pathogens in their introduced ranges, allowing them to invest more energy in producing allelopathic compounds. In their native range, spotted knapweed must balance chemical defense with protection against specialized herbivores; in North America, freed from these constraints, it can maximize its chemical warfare capabilities.

The novel weapons hypothesis also explains why restoration efforts often fail even after invasive plants are removed. Native seed banks may be depleted, mycorrhizal networks disrupted, and soil chemistry altered in ways that favor reinvasion. The allelopathic legacy left in the soil creates an inhospitable environment for native species while potentially favoring the return of the same or similar invasive species.

This evolutionary mismatch has profound implications for predicting future invasions. Plants with strong allelopathic properties in their native range should be considered high-risk for becoming invasive elsewhere, particularly in regions with no closely related native species that might share resistance mechanisms.

Recent scientific advances are revolutionizing our understanding of plant chemical warfare, revealing previously unknown mechanisms and challenging established theories about allelopathic invasion.

Breakthrough research published in 2024 has identified new classes of allelopathic compounds in invasive species that operate through unexpected pathways. Scientists studying Senecio angulatus discovered that its allelopathic effects vary dramatically based on the target species and environmental conditions, suggesting that these plants can somehow "tune" their chemical output to maximize impact. This finding challenges the traditional view of allelopathy as a passive, constant process.

New research reveals that invasive plants can alter soil microbial communities to amplify their chemical weapons' effectiveness, with garlic mustard promoting bacteria that convert its toxins into even more potent forms.

Perhaps the most intriguing discovery involves the role of soil microbiomes in mediating allelopathic effects. New research reveals that invasive plants can alter soil microbial communities to amplify their chemical weapons' effectiveness. Garlic mustard, for example, not only releases toxins but also promotes the growth of soil bacteria that convert these compounds into even more potent forms. This microbial manipulation represents a previously unrecognized dimension of plant invasion biology.

Advances in metabolomics - the study of chemical fingerprints left by cellular processes - have enabled scientists to track allelopathic compounds through entire ecosystems. Using mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance imaging, researchers can now map the three-dimensional distribution of toxins in soil, revealing hot spots of chemical concentration and pathways of dispersal. These techniques have shown that allelopathic zones extend much farther than previously thought, with Tree-of-Heaven affecting soil chemistry up to 50 feet from the parent tree.

Climate change adds another layer of complexity to allelopathic invasion. Elevated CO2 levels and rising temperatures affect both the production of allelopathic compounds and their breakdown in soil. Some studies suggest that warming temperatures may enhance the allelopathic effects of certain invaders while reducing them in others, potentially reshuffling the hierarchy of invasive threats.

Scientists are also discovering that allelopathic effects can cascade through food webs in unexpected ways. When native plants are suppressed, the insects that depend on them decline, affecting birds and other wildlife. This chemical cascade can fundamentally alter ecosystem structure from the bottom up, creating simplified biological communities dominated by generalist species.

Land managers and conservationists are developing innovative strategies that use allelopathy knowledge to combat invasive species, turning the invaders' weapons against them.

One promising approach involves timing mechanical removal to minimize allelopathic legacy effects. By pulling garlic mustard before it sets seed in April or early May, managers can prevent the next generation of chemical weapons from entering the soil. This timing is critical - too early and the plant may resprout; too late and seeds will have formed. Complete root removal is essential since even small fragments can regenerate and continue releasing toxins.

"When harvesting garlic mustard leaves, take your time and be sure to pull up the roots of the plants that are harvested. This way, you get the maximum impact on garlic mustard's invasion for your work."

- Katie Toner, Conservation Easement Steward, Heritage Conservancy

Restoration ecologists are experimenting with "nurse plants" - native species that show natural resistance to allelopathic chemicals. These pioneers can establish in contaminated soils and gradually improve conditions for more sensitive species. Some native grasses, for instance, produce their own allelopathic compounds that can neutralize invader toxins, creating safe zones for restoration.

Innovative biological control methods target the chemical weapons directly rather than the plants themselves. Scientists have identified soil bacteria and fungi capable of breaking down specific allelopathic compounds. By inoculating restoration sites with these microorganisms, managers can accelerate the detoxification of contaminated soils. This approach has shown particular promise for sites affected by persistent chemicals like those from Tree-of-Heaven.

The development of allelopathy-based bioherbicides represents another frontier. Researchers are investigating isolated allelochemicals as templates for new, environmentally friendly herbicides that could selectively target invasive species. Unlike broad-spectrum synthetic herbicides, these bio-based alternatives could provide precise control without collateral damage to native plants.

Some conservation groups have found creative ways to engage the public in allelopathy management. The transformation of garlic mustard into pesto creates an economic incentive for removal while raising awareness about chemical ecology. "Eat the invaders" campaigns turn ecological restoration into a culinary adventure, with foraging workshops teaching proper removal techniques to prevent spread while harvesting.

However, challenges remain significant. The persistence of allelopathic chemicals in soil means that restoration often requires long-term commitment and repeated interventions. Sites may need multiple years of active management before native plants can successfully reestablish. The cost of comprehensive restoration, including soil remediation and mycorrhizal reintroduction, can exceed $10,000 per acre for severely infested sites.

The impacts of allelopathic invasion extend far beyond simple plant replacement, triggering cascading effects that fundamentally alter ecosystem functioning.

When allelopathic invaders suppress native plant diversity, they disrupt entire food webs. Specialist insects that depend on specific native plants face local extinction when their host plants disappear. The West Virginia white butterfly, for example, has declined precipitously as garlic mustard replaces native toothworts, its primary host plants. The butterfly's larvae cannot survive on garlic mustard despite the chemical similarities that attract egg-laying females - a deadly evolutionary trap.

Soil chemistry changes induced by allelopathic invasion can persist for decades. The disruption of mycorrhizal networks doesn't just affect individual plants; it breaks down the underground communication and nutrient-sharing systems that forests depend on. These "wood wide web" networks allow trees to share resources and warning signals about pest attacks. When garlic mustard destroys these fungal networks, it isolates plants from their community support system.

Spotted knapweed invasion in Montana alone costs ranchers millions annually in lost forage production, with some areas seeing wildlife and livestock forage reduced by up to 90%.

Nutrient cycling - the fundamental process that sustains ecosystem productivity - becomes altered under allelopathic invasion. Many invasive plants produce leaf litter that decomposes at different rates than native species, changing soil nutrient availability. Tree-of-Heaven leaves decompose rapidly, releasing a pulse of nutrients that favors fast-growing weedy species over slow-growing native plants adapted to nutrient-poor conditions.

Hydrological cycles can shift when allelopathic invaders replace deep-rooted native plants with shallow-rooted monocultures. This change affects water infiltration, increasing surface runoff and erosion while reducing groundwater recharge. Stream ecosystems downstream suffer from increased sedimentation and altered flow patterns.

Wildlife populations respond to these botanical changes in complex ways. Generalist species may initially benefit from the abundant biomass of invasive plants, but nutritional quality is often lower than native alternatives. Deer browsing on garlic mustard, for instance, receive less protein and minerals than from native forest herbs. Over time, this nutritional deficit can affect reproduction and survival rates.

The economic impacts cascade through human systems as well. Spotted knapweed invasion in Montana alone costs ranchers millions annually in lost forage production. Recreation areas become less attractive as diverse wildflower meadows transform into monoculture wastelands. Property values can decline in areas heavily infested with allelopathic invaders.

Perhaps most concerning is the potential for "invasion meltdown" - where multiple invasive species facilitate each other's spread through complementary impacts. Allelopathic plants that suppress native competitors create opportunities for other invaders to establish, leading to accelerating ecosystem degradation that becomes increasingly difficult and expensive to reverse.

As we look toward the future of managing allelopathic invasion, new challenges and opportunities are emerging that will shape conservation strategies for decades to come.

Climate change is redistributing the battle lines of invasion. As temperature and precipitation patterns shift, the geographic ranges of allelopathic invaders are expanding. Garlic mustard, once limited by cold winters in its northern range, now threatens previously safe boreal forests. Meanwhile, drought stress in western regions may intensify the allelopathic effects of existing invaders, giving them even greater competitive advantages.

Emerging technologies offer new weapons in the fight against chemical invasion. Environmental DNA (eDNA) techniques can detect invasive species presence before visible populations establish, allowing for rapid response to new invasions. Drone-based hyperspectral imaging can identify allelopathic invaders across large landscapes by detecting subtle changes in vegetation chemistry, enabling targeted management at previously impossible scales.

The development of "smart" restoration techniques that work with natural processes shows particular promise. Researchers are exploring the use of allelopathic crop rotations to prepare invaded sites for native plant restoration. Rye cover crops, which can reduce weed emergence by up to 80%, could precondition soils before native species reintroduction. This approach transforms allelopathy from problem to solution.

Genetic research is opening new frontiers in understanding and potentially controlling allelopathic invasion. Scientists have identified the genes responsible for producing allelopathic compounds in several invasive species. This knowledge could lead to targeted biological controls that silence these genes or development of native plant varieties with enhanced resistance to invasive plant toxins.

International cooperation is becoming crucial as global trade continues to accelerate the movement of potentially invasive species. New risk assessment protocols incorporating allelopathic potential are being developed to prevent future invasions before they occur. Countries are sharing databases of chemical profiles from known invaders, creating an early warning system for allelopathic threats.

Citizen science initiatives are multiplying the boots on the ground for invasion detection and management. Smartphone apps that can identify invasive plants and report their locations are creating real-time invasion maps. Community "bioblitzes" focused on invasive species removal combine education with action, building public understanding of allelopathy while accomplishing restoration work.

The discovery of allelopathy's role in plant invasion has fundamentally changed how we understand and manage invasive species. No longer can we view invasion as simply a matter of faster growth or better seed dispersal. Instead, we must recognize it as chemical warfare - an invisible battle being fought in the soil beneath our feet.

The implications extend beyond ecology into questions about the future of our landscapes. As novel chemical weapons continue to give invasive plants unprecedented advantages, entire ecosystems hang in the balance. The forests, prairies, and wetlands that define our natural heritage face transformation into simplified, chemically defended monocultures unless we develop effective counterstrategies.

Yet there is reason for cautious optimism. Our growing understanding of allelopathic mechanisms is leading to more sophisticated and effective management approaches. By working with natural processes rather than against them, using the invaders' own weapons against them, and engaging communities in the fight, we're developing a new paradigm for invasion biology.

The chemical war between invasive and native plants will likely intensify as climate change and global trade create new opportunities for invasion. But armed with knowledge of allelopathy and innovative management tools, conservationists are better equipped than ever to protect native ecosystems. The battle may be invisible, but its outcomes will shape the visible world for generations to come.

Understanding plant chemical warfare isn't just an academic exercise - it's essential for anyone who cares about preserving biodiversity and ecosystem function. Whether you're a land manager dealing with garlic mustard, a gardener battling Tree-of-Heaven, or simply someone who values native wildflowers, recognizing the role of allelopathy in invasion provides crucial insights for action.

The next time you walk through a forest dominated by a single invasive species, remember that you're witnessing the aftermath of chemical warfare. Those missing wildflowers weren't simply outcompeted - they were poisoned, their fungal partners destroyed, their seeds prevented from germinating by an arsenal of toxins evolved half a world away. But also remember that we're learning to fight back, turning the invaders' chemical weapons into tools for restoration and protection of the native ecosystems we cherish.

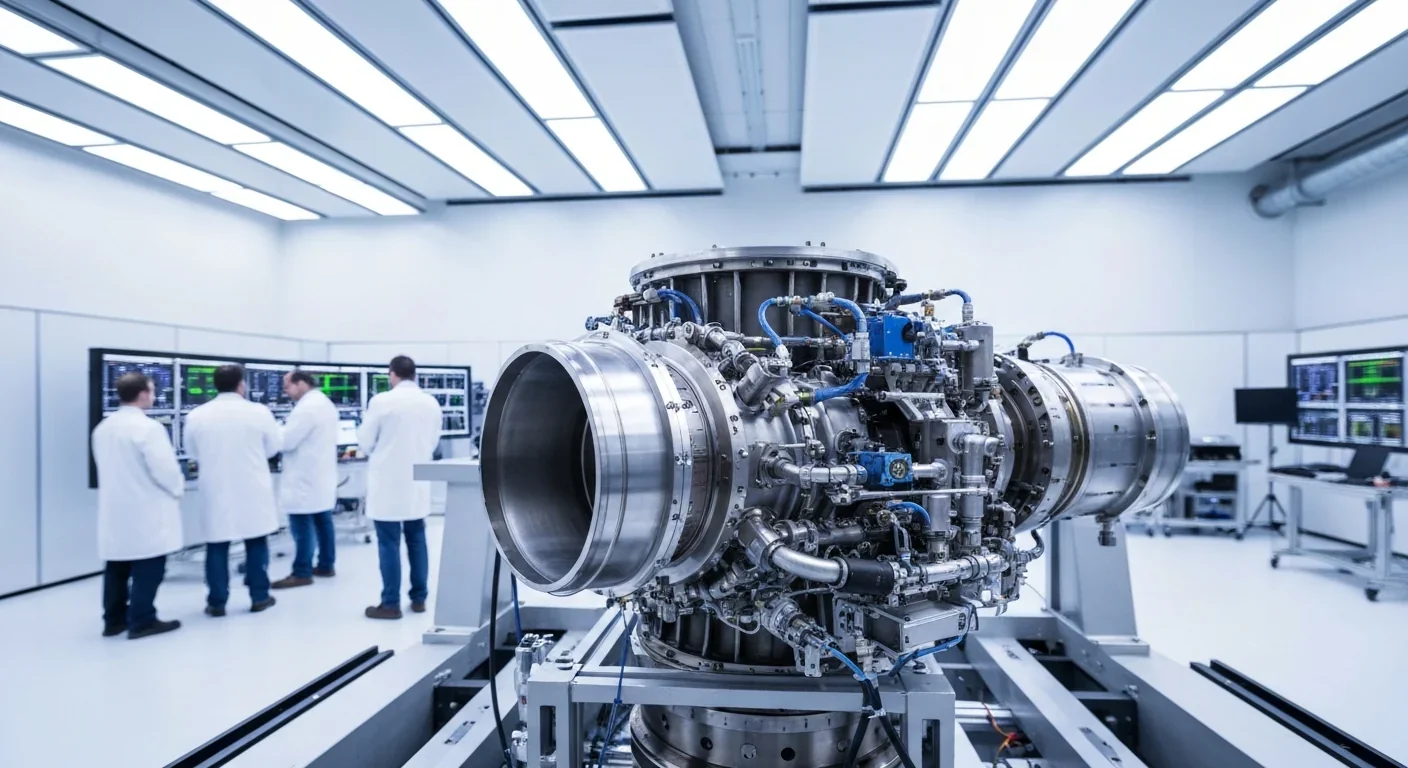

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

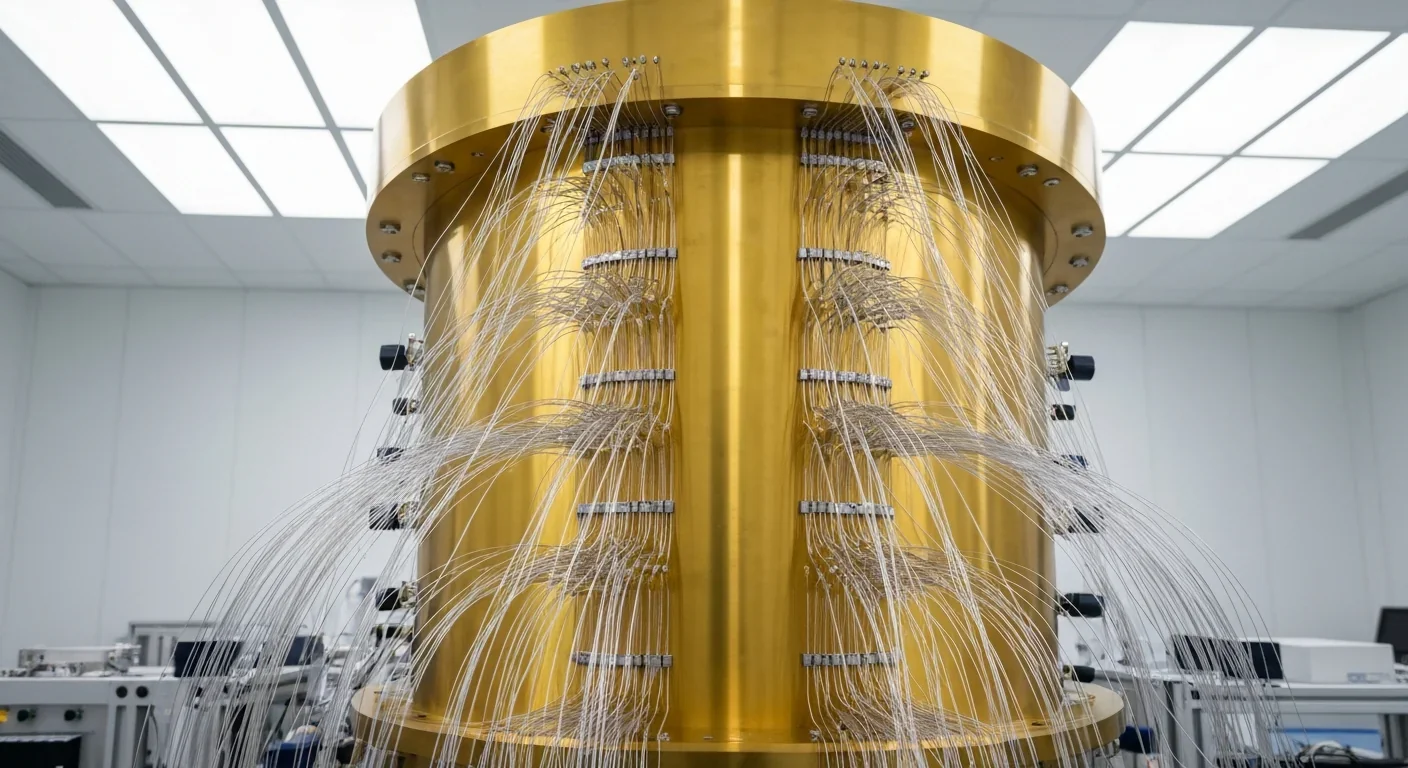

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.