Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Social insects use volatile chemical compounds called alarm pheromones to instantly transform entire colonies into coordinated defense forces. From honeybees' banana-scented isopentyl acetate to fire ants' pyrazine signals, these molecular panic buttons trigger behavioral cascades within seconds, revealing sophisticated collective intelligence emerging from simple chemical communication.

Walk too close to a beehive and you might catch a whiff of something oddly familiar: bananas. That fruity scent isn't coming from a forgotten lunch, it's the smell of chemical panic. A single crushed bee releases isopentyl acetate, a volatile compound that transforms a calm colony into a coordinated defense force within seconds. This isn't random aggression but a sophisticated communication system millions of years in the making, one that reveals how simple chemistry can orchestrate astonishingly complex collective behavior.

The alarm pheromones of social insects represent one of nature's most elegant solutions to the problem of group defense. While individual insects possess limited cognitive abilities, their chemical signaling systems enable colony-wide responses that rival the coordination of much larger-brained animals. Understanding these systems isn't just academic curiosity: it's reshaping how we approach pest management, revealing fundamental principles of collective intelligence, and demonstrating how evolutionary pressures sculpt communication across species boundaries.

At the molecular level, alarm pheromones are surprisingly diverse. Honeybees rely on a complex blend of more than 40 compounds released from the Koschevnikov gland near the sting shaft, with isopentyl acetate as the primary active ingredient. But they're not alone in their chemical arsenal: the mandibular glands produce 2-heptanone, a compound that doesn't just alarm other workers but actually anesthetizes intruders, allowing bees to physically remove threats from the hive.

Ants took a different chemical route. Many species produce pyrazine compounds, nitrogen-containing ring structures that create their characteristic sharp, pungent odor. Fire ants (Solenopsis invicta) synthesize 2-ethyl-3,6-dimethylpyrazine, while trap-jaw ants (Odontomachus) manufacture 2,5-dimethyl-3-isoamylpyrazine. These aren't arbitrary choices: each compound's volatility, persistence, and receptor-binding properties have been fine-tuned by natural selection for optimal alarm signaling in specific ecological contexts.

Fire ant alarm systems can mobilize 60% of nearby workers within five seconds and achieve full colony defense in just two minutes, demonstrating the extraordinary efficiency of chemical panic signals.

Hornets and wasps add yet another dimension to this chemical diversity. The Asian giant hornet employs a three-component system: 2-pentanol, isoamyl alcohol, and 1-methylbutyl 3-methylbutanoate. What's remarkable is the synergy: 2-pentanol alone produces only mild alarm, but the combination of all three compounds triggers intense, coordinated aggression. The European hornet uses a completely different primary compound, 2-methyl-3-butene-2-ol, demonstrating that even closely related species can evolve distinct chemical solutions to the same defensive challenge.

This chemical diversity reflects the independent evolution of alarm systems across multiple insect lineages. Research shows that alarm pheromones range from terpenoids in aphids and termites to acetates and ketones in bees to formic acid in ants, each tailored to the sensory ecology and defensive needs of its species.

The speed of alarm pheromone responses is staggering. When a fire ant worker detects 2-ethyl-3,6-dimethylpyrazine, specialized receptors on its antennae bind the molecule within milliseconds. Within five seconds, 60% of workers within a 5-centimeter radius become agitated and begin recruiting additional defenders. By two minutes, the entire colony has mobilized for defense.

This isn't simple reflexive behavior. Transgenic ant research using calcium-sensitive proteins revealed that alarm pheromones activate just six specific glomeruli out of more than 500 in the ant brain. Think of it as a neural panic button: these dedicated circuits bypass normal sensory processing to trigger immediate defensive responses. Worker ants exposed to alarm signals scramble to gather eggs and larvae, evacuating vulnerable brood while other workers rush toward the threat.

"We were expecting that a large portion of the antennal lobe would show some kind of response to these alarm pheromones, but instead we saw that the responses were extremely localized."

- Taylor Hart, neuroscientist studying transgenic ants

Honeybees show an equally dramatic cascade. When a bee stings, the act tears the barbed stinger from her body, rupturing the venom sac and associated glands. This fatal injury releases a plume of alarm pheromones that nearby workers detect almost instantly through specialized receptors on their antennae. The introduction of these chemicals triggers an immediate shift: previously docile foragers become alert and aggressive, their stinging threshold drops dramatically, and they begin to recruit additional defenders through repeated alarm pheromone release. It's a positive feedback loop where each defensive sting amplifies the signal, rapidly escalating colony mobilization.

The behavioral responses aren't uniform, though. Research demonstrates that the same alarm pheromone can trigger different behaviors depending on context. Near the nest, workers aggregate and attack; far from the nest, they may disperse to avoid drawing predators to vulnerable brood. This context-dependent flexibility shows that alarm pheromones aren't simple on/off switches but information-rich signals interpreted through the lens of location, colony state, and individual experience.

Recent advances in insect neuroscience have revealed how alarm pheromones hijack sensory systems to produce such reliable responses. Studies of ant brains discovered that social insects possess a specialized communication processing center not found in solitary species, a sensory hub where all panic-inducing alarm pheromones converge. This centralized architecture differs markedly from honeybees, which rely on multiple distributed brain regions to process a single pheromone. The evolutionary implication is clear: ants evolved a dedicated neural substrate for alarm integration, a kind of chemical command center that prioritizes threat responses above all other sensory input.

The molecular machinery underlying alarm detection is equally sophisticated. Research on fire ants identified NPC2 proteins as key players in alarm pheromone recognition. These proteins don't just transport pheromone molecules to receptors; they act as receptors themselves, binding 2-ethyl-3,6-dimethylpyrazine with dissociation constants around 1 micromolar. When researchers knocked down NPC2 expression using RNA interference, treated ants lost their ability to detect alarm pheromones entirely. They no longer clustered defensively, their electroantennogram responses dropped by 70%, and they failed to mount colony-wide defensive cascades. This dual role of carrier and receptor represents a fascinating convergence with vertebrate sensory systems, where similar proteins mediate both lipid transport and signaling.

Perhaps most surprising is the finding that alarm pheromone systems show cross-species recognition. Yellow jacket wasps of three different species, western, common, and German, all produce chemically similar alarm pheromones and respond to each other's signals. This shared chemical language suggests either common ancestry or convergent evolution driven by shared predators. Either way, it reveals a strategic advantage: colonies can respond preemptively to threats attacking nearby nests, even of different species. It's chemical eavesdropping in service of mutual defense.

The diversity of alarm pheromones across social insects tells a story of evolutionary innovation under intense predation pressure. Why did bees evolve acetate-based systems while ants converged on pyrazines? The answer lies in the physics and chemistry of signal transmission.

Acetates like isopentyl acetate are highly volatile, spreading rapidly through air to recruit defenders quickly. But this volatility comes with a tradeoff: the signal dissipates within minutes, limiting false alarms from old threats. Honeybees, which face aerial predators and mammalian raiders that attack quickly, benefit from this rapid-but-brief warning system. The concentration of isopentyl acetate even varies among bee subspecies: Africanized honeybees produce higher levels than European bees, corresponding to their more aggressive defensive behavior.

The alarm pheromone of honeybees smells like bananas because isopentyl acetate is the same compound that gives bananas their characteristic fruity aroma, a coincidence of chemistry rather than evolutionary design.

Pyrazines in ants offer different advantages. These nitrogen-containing compounds are less volatile but more persistent, hanging in the air and on surfaces for extended periods. For ground-dwelling ants defending subterranean nests, this persistence is valuable: it marks threatened areas and maintains alert status during prolonged attacks. The repeated evolution of pyrazine-based alarm systems across unrelated ant lineages, from fire ants to trap-jaw ants, demonstrates convergent selection favoring this chemical class for terrestrial defense.

Hornets reveal yet another evolutionary strategy: chemical synergy. The three-component system of the Asian giant hornet isn't redundancy but optimization. Field tests showed that single compounds produced weak responses, but the full blend triggered dramatically more aggressive behavior. This suggests that hornet colonies evolved sensitivity to specific concentration ratios, a form of chemical encoding that allows more nuanced threat assessment. A partial blend might signal a minor disturbance, while the full cocktail indicates a serious attack requiring maximum mobilization.

The anatomical sources of these pheromones also show evolutionary innovation. Honeybees release alarm compounds from glands near the sting, ensuring that defensive stinging automatically triggers recruitment of additional defenders. Ants produce alarm pheromones from mandibular glands, linking chemical signaling to their primary defensive weapon: biting. Termite soldiers secrete alarm compounds from the nasus, a specialized frontal gland. Each anatomical specialization couples pheromone release to the species' primary defensive behavior, creating a seamless link between individual action and colony response.

Not all colony members produce or respond to alarm pheromones equally. Honeybee workers are born with essentially no isopentyl acetate in their Koschevnikov glands. Production begins gradually, peaking at 2-3 weeks of age, precisely when workers transition to guard duties at the hive entrance. Queens produce no alarm pheromone at all, their role being reproduction rather than defense. This developmental regulation ensures that the insects most likely to encounter threats are also the ones most capable of sounding the alarm.

The response to alarm pheromones also varies by age and caste. Young nurse bees deep in the hive show muted responses to alarm signals compared to older guard bees. This makes ecological sense: nurses caring for vulnerable brood shouldn't abandon their charges at the first hint of distant danger. Only when alarm pheromone concentrations reach levels indicating an imminent threat do nurse bees shift to defensive mode, prioritizing colony survival over individual brood care.

Africanized bees illustrate how alarm systems can be genetically tuned for different defensive strategies. These bees don't just produce more isopentyl acetate; they also respond to lower concentrations and maintain alert states longer. The result is a hair-trigger defensive system that made Africanized bees successful in environments with high predation pressure but also more dangerous to humans and livestock. Natural selection doesn't optimize for friendliness; it optimizes for colony survival, and sometimes that means hyper-vigilance.

Understanding alarm pheromones has immediate practical value. Beekeepers have long used smoke during hive inspections, and we now know why it works: smoke masks alarm pheromones, preventing the cascade that turns inspection into mass stinging. The smoke doesn't calm the bees directly; it interferes with their chemical communication, breaking the alarm feedback loop before it escalates.

"There seems to be a sensory hub in the ant brain that all the panic-inducing alarm pheromones feed into."

- Daniel Kronauer, ant neuroscientist

This principle is being extended to pest management. Synthetic alarm pheromones can be used to disrupt pest insect colonies, triggering false alarms that waste energy and reduce foraging efficiency. Alternatively, alarm pheromone analogs can repel pest species from crops or structures without toxic chemicals. Fire ants exposed to synthetic 2-ethyl-3,6-dimethylpyrazine abandon nests, allowing targeted control without broad-spectrum insecticides that harm beneficial insects.

The flip side is equally valuable: masking or blocking alarm pheromones can prevent defensive responses during necessary human-insect interactions. Agricultural settings where bees provide pollination services but pose stinging hazards could use pheromone-blocking compounds to reduce aggression during harvest or equipment maintenance. The goal isn't to eliminate defensive behavior entirely but to modulate it context-appropriately.

Research into cross-species pheromone recognition among wasps suggests potential for area-wide control strategies. If multiple pest wasp species respond to each other's alarm pheromones, a single synthetic compound might repel entire communities. This kind of broad-spectrum chemical communication disruption could be more efficient and sustainable than species-specific approaches, though careful ecological assessment is needed to avoid unintended effects on beneficial wasps.

What alarm pheromones ultimately reveal is how simple chemical signals can generate sophisticated collective intelligence. Individual ants or bees follow straightforward behavioral rules: detect chemical, assess concentration, execute appropriate response. Yet these simple algorithms, executed in parallel by thousands of individuals, produce colony-level behaviors that appear almost intentional. Alarm cascades don't require central coordination or individual intelligence; they emerge from the interaction of many agents following local chemical cues.

This distributed decision-making has surprising parallels to human systems. Financial markets can experience panic cascades where individual fear responses amplify into crashes. Social media algorithms create attention cascades where individual shares trigger exponential information spread. The mathematics underlying these phenomena, positive feedback loops modulated by decay rates and threshold effects, are essentially identical whether we're discussing isopentyl acetate diffusing through a beehive or panic diffusing through a trading floor.

But insect colonies have had hundreds of millions of years to refine their systems. The precisely calibrated volatility of alarm pheromones, the anatomical coupling of chemical release to defensive actions, the developmental tuning of production and sensitivity, all represent evolutionary solutions to coordination problems that human organizations still struggle with. How do you alert a group to danger without triggering stampedes? How do you maintain appropriate vigilance without wasting resources on false alarms? How do you scale collective responses to threat severity?

Social insects solved these problems through chemistry. Their alarm pheromone systems incorporate signal amplification (each defensive sting releases more pheromone), automatic decay (volatile compounds dissipate quickly), threshold effects (responses scaled to concentration), and context-dependence (location relative to nest modulates behavior). These design principles could inform how we build better alert systems, from emergency notifications to cybersecurity threat responses.

The most profound insight from alarm pheromone research may be how it reframes our understanding of communication itself. We tend to think of communication as transmission of information between separate entities, a sender encoding meaning that a receiver decodes. But alarm pheromones blur these boundaries. The compound released by a dying bee doesn't "inform" other bees of danger in the way a shout warns humans. It directly alters the neurochemistry of nearby workers, shifting their behavioral states through molecular interaction rather than semantic content.

This is communication as chemical engineering: molecules binding to receptors, triggering neural cascades, reconfiguring behavioral priorities. There's no interpretation, no cognitive processing in any traditional sense. The message is the effect. And yet the result is coordinated group behavior that responds appropriately to external threats, demonstrating that what we call intelligence or decision-making might not require internal representations or conscious deliberation at all.

NPC2 proteins in fire ants bind alarm pheromones with micromolar precision, and knocking down their expression eliminates defensive responses entirely, revealing how a single molecular system can control colony-wide behavior.

Recent work on the dedicated brain regions processing alarm pheromones suggests these systems may have driven the evolution of specialized neural architecture in social insects. The centralized panic processing in ant brains represents a cognitive commitment: brain space dedicated specifically to group coordination that solitary insects don't possess. Sociality didn't just change insect behavior; it changed insect neurobiology, creating new sensory organs and processing centers that exist only in the context of colony life.

As we develop artificial intelligence and design algorithms for multi-agent systems, insect alarm pheromones offer unexpected lessons. How do you coordinate thousands of autonomous agents with minimal communication overhead? Insects use simple, local signals (chemical concentration gradients) that each agent can detect and respond to independently. No central controller, no complex messaging protocol, just chemicals diffusing through space and agents following concentration-dependent rules.

How do you ensure robust responses that don't trigger false positives? Insects use threshold effects and signal decay: small disturbances produce small, localized responses that die out quickly, while major threats generate cascading amplification. The system self-tunes based on signal intensity and persistence.

How do you scale defensive responses to threat severity? Insects couple pheromone release directly to defensive actions (stinging, biting), creating automatic feedback where the intensity of the colony's response matches the intensity of its engagement with threats. More defenders engaging means more pheromone released means more defenders recruited, until the threat is eliminated or driven off.

These principles are being explored in swarm robotics, where researchers design robot collectives inspired by insect coordination. Robots that communicate through light or sound gradients rather than explicit messages can achieve insect-like coordination without the computational overhead of traditional multi-agent systems. The future of distributed artificial intelligence may look less like networked computers and more like an ant colony responding to alarm pheromones.

While we've focused on alarm pheromones, the principles extend to other aspects of insect chemical communication. Trail pheromones coordinate foraging, queen pheromones regulate reproduction, brood pheromones organize care behavior, all using the same basic mechanism: chemical signals triggering behavioral responses through evolved sensory systems. The alarm pheromone case is special only because the behaviors involved, mass aggression and coordinated defense, are so dramatically visible and so clearly adaptive.

But the underlying pattern applies more broadly: complex collective behaviors emerging from simple chemical signals and evolved response rules. This suggests that much of what appears to be social coordination, whether in insects or potentially other animals, might be reducible to chemical communication networks we're just beginning to map. The dedicated neural processing centers found in social insect brains hint that other specialized cognitive architecture awaits discovery, brain regions evolved specifically for processing the chemical languages of colony life.

What started as a question about why squashing a bee triggers a swarm leads to fundamental insights about communication, collective behavior, neuroscience, and evolution. A single molecule, isopentyl acetate, binds to a receptor, activates a neural circuit, triggers a behavior, releases more molecules, and suddenly a peaceful colony transforms into a coordinated defense force. It's chemistry becoming behavior becoming group phenomenon, illustrating that the line between chemical reaction and social action isn't as clear as we might think.

The banana smell you catch near an agitated hive isn't just an interesting scent, it's a glimpse into one of nature's most elegant communication systems, refined over millions of years of evolutionary pressure into a nearly perfect solution to the coordination problem faced by all social species: how to turn individual awareness of danger into collective action. And the answer, at least for insects, is written in the language of molecules.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

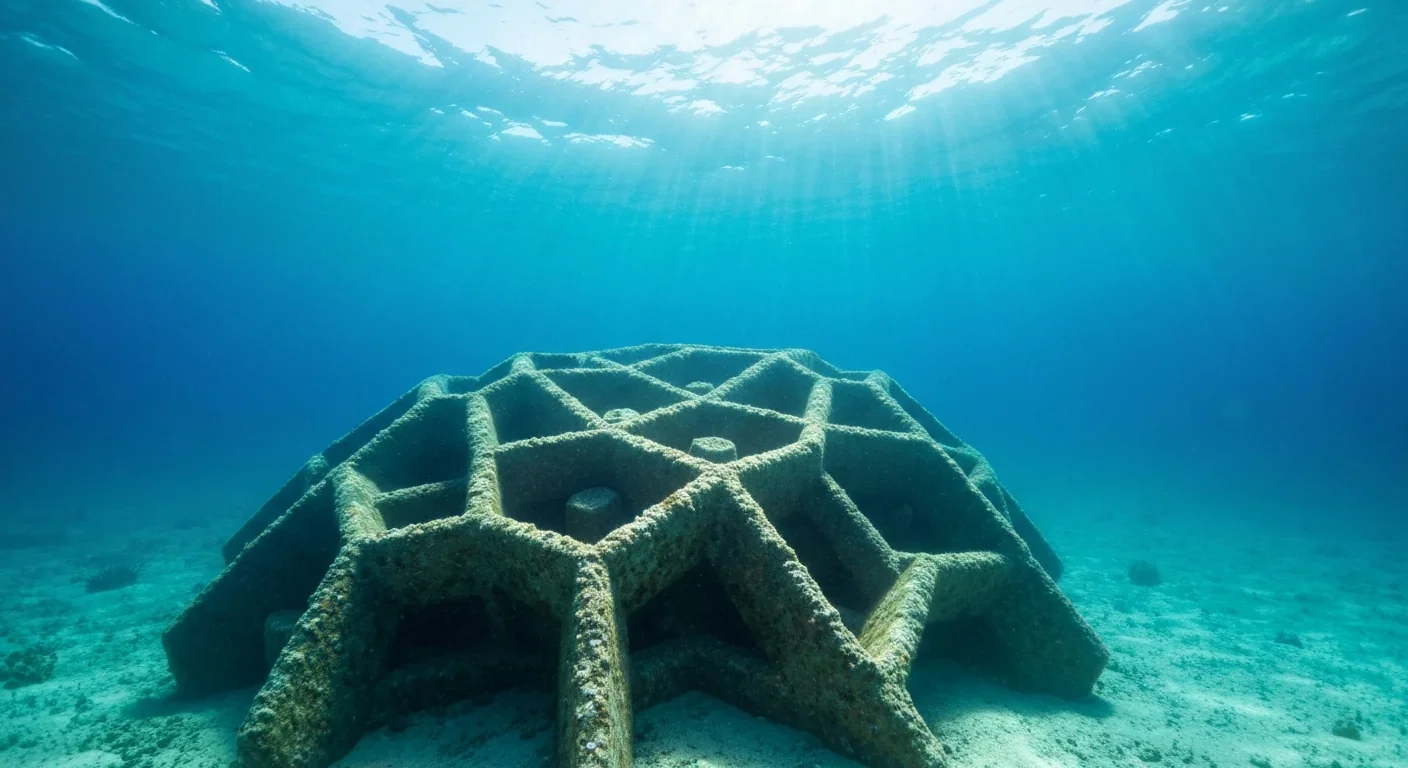

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

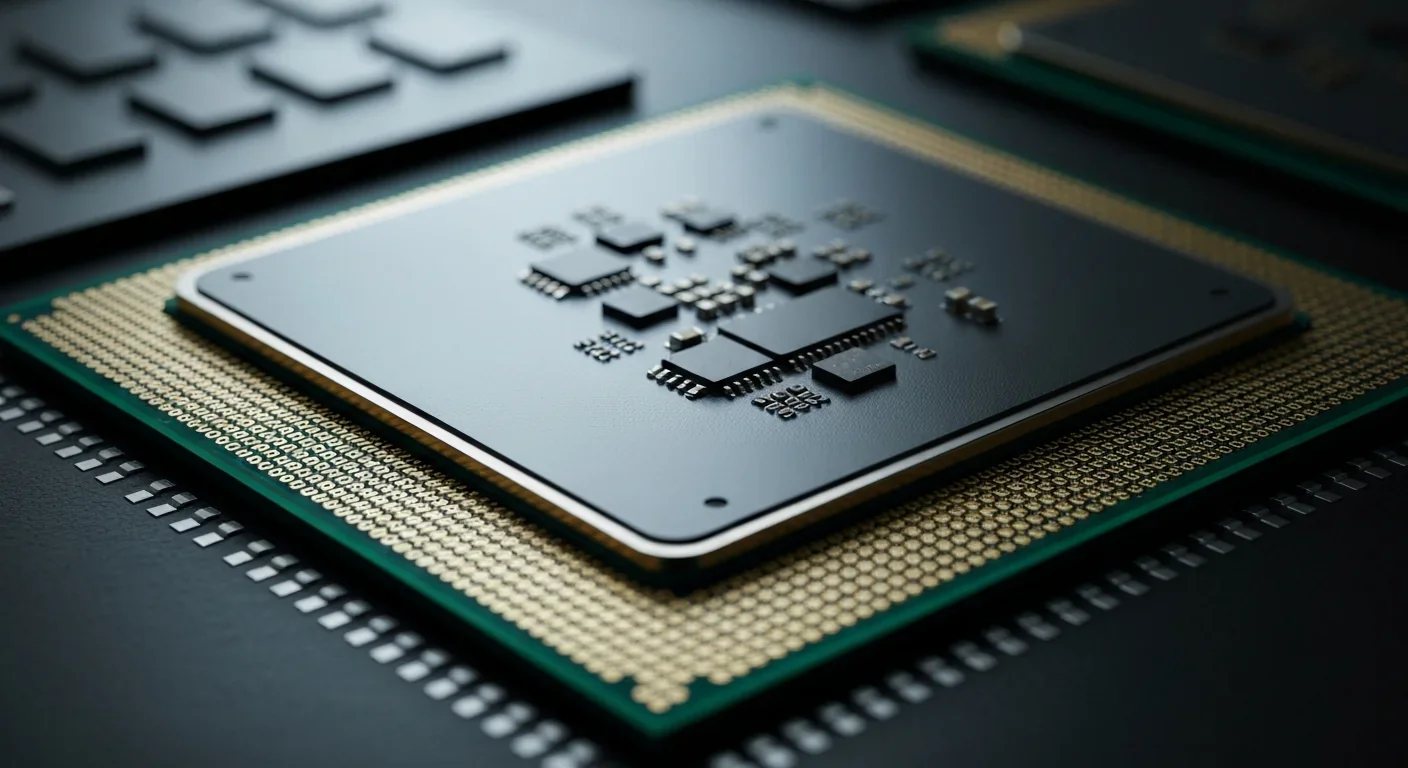

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.