Nature's First Farmers: 50 Million Years of Ant Agriculture

TL;DR: Fungi navigate their world without eyes or brains using sophisticated molecular photoreceptors that detect light and guide growth. These ancient sensory systems, discovered in proteins like the white-collar complex, allow mushrooms to bend toward light for optimal spore dispersal - demonstrating that complex perception doesn't require nervous systems.

Mushrooms don't have eyes, nerves, or brains. Yet if you place a sprouting fungal stalk in a dark room with a single beam of light, it will bend toward that light source with surprising precision. This isn't magic or coincidence - fungi have been quietly mastering the art of phototropism for hundreds of millions of years, long before animals evolved their first primitive eyes.

Recent breakthroughs in mycology reveal that fungi possess sophisticated molecular machinery capable of detecting light, interpreting its direction and intensity, and orchestrating growth responses without a single neuron. This discovery challenges our understanding of sensory perception and forces us to reconsider what it means to "see" the world.

For decades, scientists knew fungi responded to light but couldn't explain how. The breakthrough came in 1992 when researchers identified the white-collar complex in Neurospora crassa, a bread mold that serves as a model organism for fungal research. This protein complex, composed of WC-1 and WC-2, acts as the fungus's primary blue-light photoreceptor.

Unlike animal eyes with specialized photoreceptor cells, fungi integrate light detection directly into their cellular machinery. The white-collar proteins contain LOV (Light, Oxygen, Voltage) domains that physically change shape when struck by blue light photons at 470 nanometers. This conformational shift triggers a cascade of molecular events that ultimately redirects fungal growth.

Within 30 minutes of blue light exposure, WC-1 protein levels increase threefold - allowing fungi to adjust growth direction with remarkable speed.

What makes this mechanism remarkable is its elegance. Studies show that within 30 minutes of blue light exposure, WC-1 protein levels increase threefold. This rapid response allows fungi to adjust their growth direction quickly, maximizing their chances of dispersing spores into open air where wind currents can carry them.

The process begins at the molecular level. When light strikes fungal cells on one side of a fruiting body, photoreceptor proteins on that side become activated. In Phycomyces blakesleeanus - a fungus famous for its dramatic phototropic bending - at least ten genes work together to produce this response. The madA and madB genes encode proteins related to the white-collar family, forming a photoreceptor complex that initiates the entire signaling cascade.

Once activated, these photoreceptors don't just detect light - they function as light-regulated transcription factors. They bind directly to DNA and switch on genes that control cell growth and development. On the illuminated side of the stalk, growth slows down. On the shaded side, growth accelerates. This differential growth rate causes the entire structure to bend toward the light source.

Think of it like adjusting the volume on opposite sides of a room. The fungus doesn't move toward light; it grows toward it by creating an imbalance in cellular expansion. Research on Aspergillus flavus demonstrated that deletion of blue-light receptors LreA and LreB completely disrupts this process, resulting in fungi that grow larger but produce fewer spores and show abnormal structures.

While blue light dominates fungal photobiology, it's not the only color fungi can detect. Recent surveys reveal a surprising diversity of photoreceptors across the fungal kingdom. Fungi can sense and respond to a wide range of colors, each serving different biological functions.

Red light perception occurs through phytochromes, photoreceptor proteins characterized in detail in Aspergillus nidulans. These sensors help fungi distinguish between sunrise and sunset, integrating light information with their internal circadian clocks. The zoosporic fungus Blastocladiella emersonii possesses an entirely novel photoreceptor: rhodopsin-guanylyl cyclase (RGS), which combines light detection with cyclic GMP signaling - a mechanism more commonly associated with animal vision.

"The ancestor of all fungi could already see a wide range of colors - hundreds of millions of years before animals evolved their first primitive eyes."

- Fungal Photobiology Research

Cryptochromes, another class of blue-light photoreceptors, fine-tune fungal responses to light intensity and may help regulate the rate at which fungi reset their internal clocks. In Neurospora, the CRY-1 protein modulates circadian amplitude, demonstrating how light sensing integrates with time-keeping mechanisms at the molecular level.

The widespread distribution of these diverse photoreceptors suggests something profound: the ancestor of all fungi could already see a wide range of colors. This ability predates the evolution of animal eyes by hundreds of millions of years, positioning fungi as pioneers in biological light detection.

For an organism that can't photosynthesize, you might wonder why fungi care about light at all. The answer lies in reproduction and survival. Fungi spend most of their lives as underground networks of thread-like hyphae, quietly decomposing organic matter in the soil. When conditions favor reproduction, they send up fruiting bodies - the mushrooms we see - packed with millions of spores.

Those spores need to reach open air and wind currents to disperse effectively. A mushroom cap that opens inside a rotting log accomplishes nothing. By growing toward light, fungi increase the probability that their spores will launch from elevated positions with unobstructed flight paths. The common mushroom Agaricus bisporus adjusts the orientation of its fruiting bodies in response to light, behavior that directly enhances spore release effectiveness.

Research shows that Phycomyces blakesleeanus uses light cues to determine when to enter sexual or asexual reproductive cycles. Environmental perception allows these organisms to time reproduction for optimal conditions - when nutrients become limited and dispersal opportunities improve.

Beyond reproduction, light helps protect fungi from DNA damage. Ultraviolet radiation can destroy genetic material, so fungi use light detection to activate protective mechanisms. They synthesize UV-blocking compounds, halt sensitive developmental processes during peak sun exposure, and orient growth to minimize damage while maximizing dispersal opportunities.

If you want to witness fungal phototropism at its most dramatic, look no further than Phycomyces. This genus, particularly P. blakesleeanus, has earned its reputation as the superstar of light-seeking fungi. Images of Phycomyces fruiting bodies bending toward light sources look almost comical - the stalks lean at such extreme angles they seem to defy gravity.

What makes Phycomyces exceptional isn't just the intensity of its phototropic response, but its sensitivity. These fungi can detect light intensities as low as a few photons and distinguish between light sources separated by minute angular differences. The sporangiophores - specialized spore-bearing stalks - respond not only to light but also to gravity, wind, chemicals, and adjacent objects. They're integrating multiple environmental signals simultaneously without anything resembling a nervous system.

Phycomyces can detect light intensities as low as a few photons and integrate signals from light, gravity, wind, chemicals, and touch - all without a single neuron.

The helical growth pattern of Phycomyces sporangia adds another layer of complexity. As the stalk elongates and bends toward light, it spirals like a corkscrew, potentially enhancing the fungus's ability to maintain structural integrity while executing these dramatic directional changes. Researchers have identified at least ten genes required for this phototropic behavior, designated madA through madJ.

Scientists have been studying Phycomyces since the 19th century, and it continues to reveal surprises. Max Delbrück, a Nobel laureate in molecular biology, spent years investigating this organism, attracted by the precision of its sensory responses. His work helped establish Phycomyces as a model system that bridges classical physiology with modern molecular genetics.

Plants and fungi both bend toward light, but they've evolved remarkably different solutions to the same problem. Plants use phototropins - blue-light receptors called phot1 and phot2 - that trigger redistribution of the hormone auxin. This hormone accumulates on the shaded side of a stem, causing those cells to elongate faster and producing the characteristic bending toward light.

Fungi lack auxin entirely. Their phototropism relies instead on direct transcriptional control by photoreceptor proteins. The white-collar proteins in fungi function simultaneously as light sensors and gene regulators, eliminating the need for hormone intermediaries. It's a more direct molecular pathway, suited to organisms that need rapid developmental responses.

There's also a fundamental difference in purpose. Plants perform photosynthesis, so light represents an energy source - they need to maximize leaf exposure to sunlight for survival. Fungi, being heterotrophs that feed on organic matter, use light purely as an informational signal. Light tells them which way is "up" and "out," guiding reproductive structures toward optimal spore dispersal positions.

Despite these differences, both kingdoms demonstrate that phototropism is an ancient, highly conserved trait. The phenomenon occurs across diverse lineages, from the simplest algae to complex flowering plants and from primitive fungi to advanced mushrooms. This convergent evolution toward light-seeking behavior underscores its fundamental importance for terrestrial life.

The past two decades have revolutionized our understanding of how fungi perceive their environment. Advanced genetic tools, including CRISPR gene editing, now allow researchers to delete specific photoreceptor genes and observe the consequences with unprecedented precision.

One breakthrough came from studies of Aspergillus flavus, a pathogenic fungus that contaminates crops and produces dangerous aflatoxins. Researchers discovered that blue-light receptors LreA and LreB control not just growth direction but also stress tolerance, spore production, and toxin synthesis. Mutants lacking these receptors grew larger colonies but produced 90% less aflatoxin under light conditions.

"Fungi use light as a signal for the regulation of development, to guide the growth of reproductive structures, and to protect the fungal cell from DNA damage."

- Journal of Fungal Photobiology

This finding revealed an unexpected connection between light sensing and pathogenicity. Fungi apparently use photoreceptors to coordinate developmental programs with virulence traits, optimizing both reproduction and host exploitation. The practical implications are significant - understanding light-dependent regulation of toxin production could lead to agricultural interventions that suppress aflatoxin contamination.

Another major advance involved mapping the complete suite of photoreceptors across fungal genomes. Comparative analyses revealed that photoreceptor diversity isn't random - certain combinations of receptor types correlate with ecological lifestyles. Soil-dwelling fungi that fruit above ground tend to have more elaborate light-sensing systems than strictly subterranean species.

Researchers also uncovered the dynamic regulation of photoreceptor proteins themselves. After light exposure, WC-1 undergoes rapid degradation via ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal pathways. This built-in desensitization mechanism prevents overstimulation and allows fungi to respond to changing light conditions rather than just light presence. It's analogous to how your eyes adapt when you move from bright sunlight to a dimly lit room.

The sophistication of fungal photoreception raises intriguing evolutionary questions. When did fungi first acquire the ability to sense light? Phylogenetic analyses suggest that light-sensing mechanisms are ancient, potentially dating back to the earliest fungal lineages that colonized land roughly 500 million years ago.

Those pioneering terrestrial fungi faced a novel challenge: orienting themselves in a three-dimensional world very different from aquatic environments. Water scatters and filters light, making directional photoreception less useful for aquatic organisms. But on land, light becomes a reliable indicator of "up" - the direction toward open air, away from soil, where spore dispersal becomes possible.

Natural selection likely favored fungi that could detect even faint light signals and use that information to guide reproductive structures upward. Over time, this basic ability was elaborated and refined. Some lineages developed multiple photoreceptor types sensitive to different wavelengths. Others integrated light signals with circadian clocks, creating sophisticated time-and-place sensing systems.

Interestingly, the photoreceptor proteins themselves appear to have diverse evolutionary origins. White-collar proteins share structural features with other LOV-domain proteins found in bacteria and plants. Phytochromes have homologs in cyanobacteria. Cryptochromes evolved from DNA-repair enzymes called photolyases. Fungi essentially "borrowed" these light-sensing modules from various sources and repurposed them for developmental control.

This evolutionary bricolage - assembling new functions from existing parts - characterizes much of biological innovation. Fungi didn't need to invent light detection from scratch. They recruited proteins that already interacted with light for other purposes and wired them into growth-control circuits. The result is a sensory system that achieves the functional goals of vision without any of the anatomical structures we associate with seeing.

The discovery of fungal phototropism has implications that extend beyond mycology. It demonstrates that complex sensory behaviors don't require centralized nervous systems or specialized sense organs. Even single-celled organisms can achieve sophisticated environmental perception through molecular networks distributed throughout their bodies.

Fungi prove that sophisticated sensory behaviors don't require brains or specialized organs - cells themselves can function as distributed sensory processors.

This challenges the traditional hierarchy of sensory sophistication, where brains and eyes represent the pinnacle of perception. Fungi show us that cells themselves can function as sensory processors. Each hyphal tip integrates multiple environmental signals - light, gravity, chemicals, touch - and translates that information into directed growth. It's a form of distributed intelligence, with computation happening locally rather than in a central processing unit.

For scientists studying the origins of sensory systems, fungi provide crucial insights. The integration of light sensing with circadian rhythms seen in Neurospora mirrors similar connections in animals and plants. This suggests that linking photoreception to internal timekeeping represents a fundamental strategy for synchronizing biology with Earth's day-night cycles.

Fungal photobiology also offers practical applications. Agricultural scientists are exploring whether manipulating light exposure could reduce fungal diseases or mycotoxin contamination. Biotechnology companies are investigating fungal photoreceptors as potential optogenetic tools - proteins that could allow researchers to control cellular processes with light in both fungal and non-fungal systems.

Despite decades of progress, major questions remain. Scientists still don't fully understand how photoreceptor activation translates into the differential growth rates that produce bending. What genes do the white-collar proteins activate? How do those genes affect cell wall extensibility and turgor pressure on opposite sides of a growing stalk? The gap between light perception and mechanical bending needs filling.

Researchers are also exploring whether fungi use light for navigation beyond simple phototropism. Can fungi remember the direction of previous light sources? Do they compare light intensity over time to predict daily patterns? Some evidence suggests that fungi with circadian clocks can anticipate dawn, preparing their developmental machinery before light actually arrives. This implies a level of temporal integration that goes beyond simple stimulus-response reactions.

The diversity of fungal lifestyles suggests that phototropism may manifest in unexpected ways across different species. Most research focuses on a handful of model organisms like Neurospora and Phycomyces. What about the thousands of other fungal species, many of which remain unstudied? Do aquatic fungi sense light differently from terrestrial species? How do parasitic fungi that live inside host tissues use photoreception?

Another frontier involves the interaction between multiple sensory modalities. Phycomyces responds simultaneously to light, gravity, wind, and chemical signals. How does the organism integrate these sometimes-conflicting cues into a coherent behavioral output? Understanding multisensory integration in fungi could reveal general principles applicable to all sensory systems, including our own.

The story of fungal phototropism ultimately asks us to expand our definition of sensing and perceiving. We tend to think of vision as something that happens in eyes and is processed by brains. Fungi remind us that perception can be simpler and more distributed, yet still remarkably effective.

When a mushroom bends toward light, is it "seeing"? Not in any conventional sense. There's no image formation, no spatial map of the visual world, no conscious awareness of light. Yet the fungus detects photons, determines their direction, and responds adaptively. It accomplishes the functional goal of vision - using light to navigate the environment - through an entirely different mechanism.

This has philosophical implications for how we understand minds and experience. If fungi can achieve sophisticated sensory behaviors without nervous systems, what does that tell us about the minimal requirements for perception? The fungus doesn't have experiences, at least not as we understand them. But it processes information about its environment and changes behavior accordingly. That's the essence of sensing, stripped down to its basic components.

"Perhaps the most profound lesson is humility. For centuries, humans viewed fungi as primitive organisms. Now we recognize them as sophisticated entities with ancient sensory systems."

- Contemporary Mycology

Perhaps the most profound lesson is humility. For centuries, humans viewed fungi as primitive organisms, barely more than decomposing mush. Now we recognize them as sophisticated entities with ancient sensory systems, complex chemical communication networks, and problem-solving abilities that don't require neurons. They've been mastering life's challenges for hundreds of millions of years, developing solutions radically different from our own.

The next time you see a mushroom pushing up through leaf litter, consider what it accomplished to reach that position. It detected faint light filtering through soil and debris. It integrated that signal with information about gravity, moisture, and nutrients. It coordinated the growth of millions of cells to thrust a fruiting body upward, positioning its spores for optimal dispersal. All without eyes, without nerves, without thought - just elegant molecular machinery executing an ancient program written in proteins and genes.

Fungi see their world not with eyes but with their entire being, every cell a potential photoreceptor, every molecule a possible sensor. In this alien mode of perception, we glimpse the beautiful diversity of solutions that evolution generates for life's universal challenges. We're all trying to navigate the same world, but fungi found their way long before animals opened their first eyes.

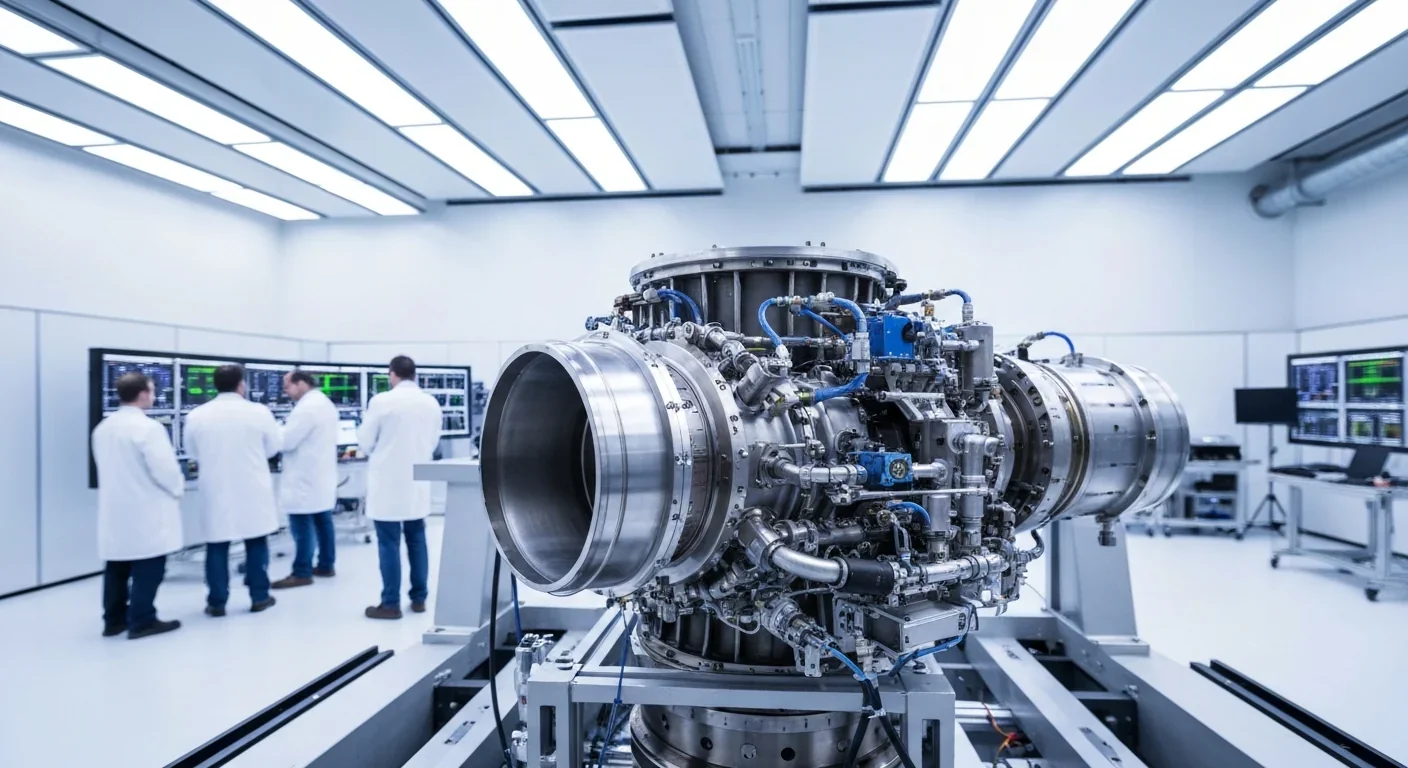

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

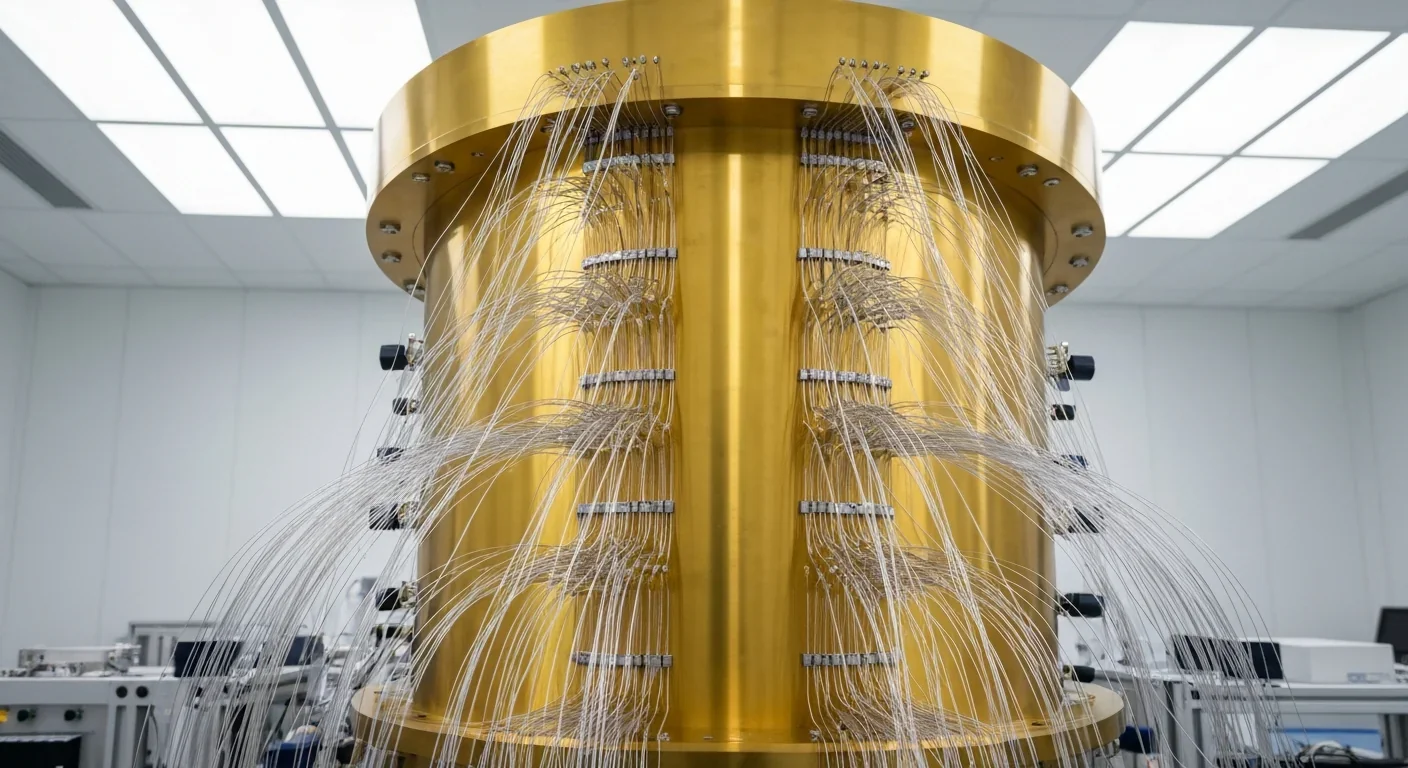

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.