Nature's First Farmers: 50 Million Years of Ant Agriculture

TL;DR: Scientists can culture only 1% of bacterial species, but breakthrough technologies like metagenomics, single-cell genomics, and innovative devices are finally revealing the hidden 99% of microbial life.

For over a century, microbiologists have faced an uncomfortable truth: they can only study about 1% of bacterial species in any given environment. The rest remain stubbornly resistant to standard laboratory techniques, creating a massive blind spot in our understanding of life on Earth. This phenomenon, known as the "great plate count anomaly," means that when scientists sample soil, ocean water, or even human gut bacteria and try to grow them in petri dishes, roughly 99% refuse to cooperate.

Think about that for a moment. We've sequenced the human genome, sent robots to Mars, and developed artificial intelligence, yet we can't even grow most of the microbes that surround us and live inside us. It's like being an ornithologist who can only observe 1% of bird species while the other 99% remain invisible. This hidden majority has earned a fitting name: microbial dark matter.

But something remarkable is happening. A convergence of cutting-edge technologies is finally cracking open this hidden world, revealing organisms so fundamentally different that they're rewriting what we thought we knew about the tree of life itself.

The traditional approach to studying bacteria hasn't changed much since Louis Pasteur's time. You take a sample, spread it on a nutrient-rich agar plate, incubate it, and watch colonies grow. It works brilliantly for the small fraction of bacteria that happen to thrive under these artificial conditions. For everyone else, it's like trying to grow a deep-sea fish in a goldfish bowl.

The problem isn't that these bacteria are dead or inactive. They're alive and thriving in their natural environments. They just won't grow when removed from those environments and placed in standard laboratory media.

Several factors conspire against cultivation. Many bacteria have incredibly slow growth rates, doubling perhaps once a week or even once a month, while lab techniques are optimized for fast-growing organisms that divide every few hours. Others require extremely specific environmental conditions that are nearly impossible to replicate: precise oxygen levels, particular pH ranges, specific mineral concentrations, or exact temperatures.

But the most fascinating obstacle is dependency. A huge proportion of unculturable bacteria are obligate symbionts that literally cannot survive without their partners. They've evolved in such tight relationships with other organisms that they've lost the genetic machinery needed for independent life. Trying to grow them alone is like trying to operate a car engine without fuel, oil, or a transmission. It might technically be an engine, but it's not going anywhere.

In a single gram of soil, there might be 10 billion bacteria representing thousands of species, but standard culturing methods will only capture a tiny fraction.

Some bacteria exist in what scientists call a "viable but non-cultivable" state. They're metabolically active but won't divide under standard conditions. It's a survival strategy, allowing them to persist through unfavorable periods, but it makes them effectively invisible to culture-based techniques.

The numbers are staggering. In a single gram of soil, there might be 10 billion bacteria representing thousands of species, but standard culturing methods will only capture a tiny fraction. The rest remain present but undetectable, their genetic material mixed into the sample like needles in a haystack.

This isn't just an inconvenience for microbiologists. It represents a fundamental gap in our understanding of how ecosystems function, how nutrients cycle through environments, and how microbial communities shape everything from soil fertility to human health.

Consider the human gut microbiome. We now know it contains trillions of bacteria playing crucial roles in digestion, immunity, and even mental health. But even with modern techniques, we can only culture a fraction of them. The majority remain mysterious, their functions inferred rather than directly observed.

Recent metagenomic analyses suggest that 42% of bacterial diversity still lacks any genomic data whatsoever. These aren't rare organisms hiding in extreme environments. They're everywhere, in massive numbers, performing functions we can barely guess at.

"The accepted gross estimate is that as little as one percent of microbial species in a given ecological niche are culturable."

- Microbial Dark Matter Research

The implications extend beyond pure science. Many antibiotics and other valuable compounds have been discovered by culturing soil bacteria and screening their chemical products. If we can only culture 1% of bacteria, what pharmaceutical treasures might the other 99% contain? What novel enzymes, metabolic pathways, or biological mechanisms are we missing?

The breakthrough came from a simple insight: if you can't grow bacteria, study their DNA directly. This approach, called metagenomics, revolutionized microbiology by treating entire environmental samples as a collective genome soup.

Instead of isolating individual species, researchers extract all the DNA from a sample, sequence everything at once, and then use computational tools to reconstruct individual genomes from the mixed data. It's like taking a jigsaw puzzle where all the pieces from dozens of different puzzles have been mixed together, then sorting them back into complete pictures based on how the edges match.

The technique works because different bacteria have characteristic DNA signatures. By looking at patterns in the sequence data, algorithms can cluster pieces that likely came from the same organism. When enough pieces cluster together, you can assemble a complete or near-complete genome without ever having seen the actual bacterium under a microscope.

This culture-independent genomics has revealed entire branches of the tree of life that were completely unknown. In 2016, researchers at UC Berkeley announced the discovery of thousands of new bacteria through metagenomic analysis, expanding the known diversity of life by more than 15%. Many of these organisms were so different from known bacteria that they required entirely new taxonomic classifications.

Single-cell genomics takes a different approach. Instead of sequencing everything in a sample at once, researchers use microfluidic techniques to isolate individual cells, then amplify and sequence the DNA from each cell separately. This avoids the computational challenge of untangling mixed genomes but requires sophisticated equipment to handle tiny volumes and single molecules of DNA.

While genomic approaches revealed the existence of unculturable organisms, they couldn't replace the insights gained from actually growing bacteria and studying their behavior. That required a different innovation: the isolation chip, or iChip.

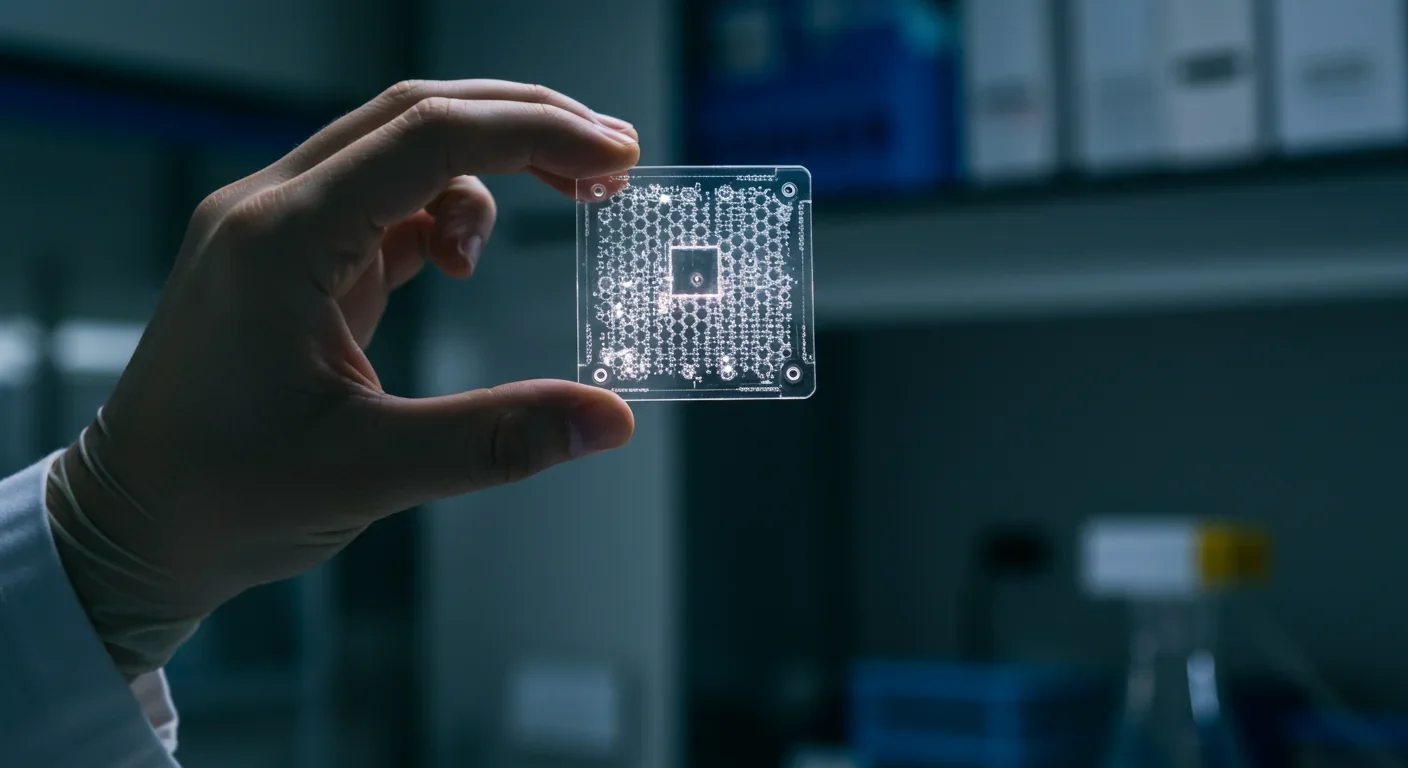

The iChip is elegantly simple. It's essentially a device with hundreds of tiny chambers, each large enough to hold a few bacteria. After loading a diluted environmental sample so that most chambers contain just one or a few cells, the device is sealed with membranes that allow nutrients and chemical signals to pass through while keeping the bacteria contained.

Here's the clever part: the entire device is then returned to the original environment where the sample came from. A soil sample goes back into soil, a marine sample returns to the ocean. The bacteria in the chambers receive all the complex chemical cues and nutrients from their natural environment, but remain separated from each other, allowing researchers to observe and eventually isolate individual strains.

The antibiotic teixobactin, discovered using an iChip in 2015, represents the first new class of antibiotics discovered in decades from an organism that had never been successfully cultured before.

This technique has led to remarkable discoveries, including new antibiotics from previously unculturable soil bacteria. The antibiotic teixobactin, discovered using an iChip in 2015, showed effectiveness against drug-resistant bacteria and represents the first new class of antibiotics discovered in decades, found in an organism that had never been successfully cultured before.

Microfluidic cell culture platforms are extending this concept further, creating miniature ecosystems on chips where bacteria can be grown in conditions that more closely mimic their natural habitats. These "soil-on-a-chip" and similar devices allow researchers to maintain complex microbial communities while still observing individual organisms.

Perhaps the most striking discovery enabled by these new techniques is the Candidate Phyla Radiation, or CPR. This isn't just a handful of new species, it's a massive group encompassing thousands of bacterial lineages that had gone completely undetected until metagenomic techniques revealed their existence.

CPR bacteria are weird. They have unusually small genomes, sometimes less than half the size of typical bacteria, because they've lost genes for many basic cellular functions. They can't synthesize most amino acids, can't generate much of their own energy, and lack the machinery for many fundamental metabolic processes.

How do they survive? They're obligate symbionts, living in intimate association with other bacteria that provide what they're missing. Think of them as bacteria that have outsourced most of their cellular operations to partners, retaining only what makes them unique.

Recent research has found CPR bacteria in hyperalkaline ecosystems, deep oceans, human mouths, and countless other environments. They're not rare extremophiles, they're everywhere, representing a significant fraction of bacterial diversity. We just couldn't see them until now.

"Metagenomic studies have uncovered entire branches of the tree of life that were completely unknown, expanding known diversity of life by more than 15%."

- UC Berkeley Research Team

The discovery of CPR bacteria and similar groups has forced a rethinking of bacterial evolution. These organisms represent ancient lineages that branched off early in bacterial history, and their existence suggests that minimal, symbiont-dependent lifestyles might be far more common than previously thought. They also raise intriguing questions about the origins of cellular complexity and whether the earliest bacteria might have been obligate partners rather than free-living organisms.

While genomic methods reveal what's out there, growing bacteria in the lab remains essential for understanding their biology. That's driving innovation in cultivation techniques designed specifically for difficult organisms.

Co-culturing, where potential symbionts are grown together, has succeeded in cultivating bacteria that refuse to grow alone. By providing the chemical signals or metabolic products they need, researchers can sometimes trick obligate symbionts into growing outside their natural hosts.

Researchers are also developing growth media that more accurately mimic natural environments, including trace elements and complex organic compounds that standard media lack. Sometimes the missing ingredient is something as simple as a vitamin or metal ion present in the natural environment but absent from laboratory formulations.

Microfluidic platforms allow researchers to create gradients of nutrients, oxygen, or other factors, letting bacteria find their preferred conditions within the device. This is particularly useful for organisms with narrow environmental tolerances that are difficult to determine in advance.

Extended incubation periods, sometimes lasting months rather than days, have revealed slow-growing organisms that would be overgrown by faster competitors in standard cultures. By starting with extremely diluted samples and being patient, researchers can sometimes coax these organisms into forming visible colonies.

The exploration of microbial dark matter isn't just satisfying scientific curiosity, it's opening new frontiers in medicine and biotechnology. The discovery of teixobactin demonstrated that previously unculturable bacteria can be sources of novel antibiotics at a time when antibiotic resistance is becoming a critical global health threat.

Beyond antibiotics, researchers are finding new enzymes with potential industrial applications, organisms capable of breaking down environmental pollutants, and bacteria with novel metabolic pathways that could be harnessed for biofuel production or chemical synthesis.

Understanding the unculturable bacteria in the human microbiome could revolutionize personalized medicine. Many of these organisms likely play important roles in health and disease, but their contributions remain obscure because we can't easily study them. Advances in cultivation techniques are beginning to change this, potentially enabling targeted manipulation of the microbiome for therapeutic purposes.

42% of bacterial diversity still lacks any genomic data whatsoever - these organisms are everywhere, in massive numbers, performing functions we can barely guess at.

The viable but non-cultivable state has particular medical relevance, especially in understanding chronic infections and oral health. Some pathogens may persist in this state, evading detection and treatment, only to resurge later. Better understanding of what triggers bacteria to enter and exit this state could lead to more effective treatment strategies.

Recent efforts to catalog Earth's microbial diversity have revealed just how much remains unknown. A 2025 analysis found that current databases contain genomic information for only about 58% of known bacterial groups at the phylum level, with vast gaps at finer taxonomic scales.

This matters because microbial biodiversity underpins ecosystem function in ways we're only beginning to appreciate. Bacteria drive global nutrient cycles, process pollutants, support plant growth, and maintain the health of every environment on Earth. Not knowing what bacteria are present or what they do is like trying to understand a complex machine while only being able to see a few of its parts.

The ecological roles of microbial dark matter organisms are particularly intriguing. Some appear to be keystone species whose presence or absence dramatically affects entire communities, despite their low abundance. Others may serve as metabolic intermediaries, processing compounds that no single organism could handle alone.

Marine environments are proving especially rich in microbial dark matter. Ocean samples reveal thousands of bacterial groups with no cultured representatives, many of which are abundant and presumably important but whose functions remain mysterious. As ocean temperatures rise and chemistry changes, understanding these organisms becomes increasingly urgent.

Despite remarkable progress, significant challenges remain. Assembling complete genomes from metagenomic data works best for organisms that are relatively abundant in a sample. Rare organisms, even if present, may not provide enough sequence data for genome reconstruction.

The computational demands of metagenomic analysis are substantial and growing. As sequencing becomes cheaper and datasets larger, the bottleneck shifts to data processing and analysis. New algorithms and computational approaches are constantly needed to handle the flood of information.

For many applications, having a genome sequence isn't enough. You need to culture the organism to study its physiology, test its susceptibility to antibiotics, or harness it for biotechnology. While cultivation-independent methods can reveal what organisms are present and what genes they carry, they can't fully replace the insights gained from working with living bacteria.

The integration of multiple approaches, combining metagenomics with single-cell techniques, advanced cultivation methods, and traditional microbiology, is proving most effective. Each technique has strengths and limitations, and using them together provides a more complete picture than any single approach.

Looking forward, artificial intelligence and machine learning are beginning to play larger roles. Algorithms can predict which growth conditions might work for unculturable organisms based on their genomic features, suggest which organisms might be symbiotic partners, and identify promising candidates for biotechnological applications.

The exploration of microbial dark matter is fundamentally reshaping our understanding of biological diversity and evolution. The tree of life now includes vast branches that were entirely unknown a decade ago, populated by organisms so different from familiar bacteria that they challenge our definitions of what a cell can be.

These discoveries also humble our perspective. For all our technological sophistication, we've been studying a biased sample of microbial life, focusing on the small fraction that happens to grow well under artificial conditions. It's like a zoologist who has only studied zoo animals making claims about wildlife behavior, the conclusions might be accurate for the organisms studied, but they miss the full picture.

As techniques improve and more of the microbial dark matter becomes accessible, we can expect surprises. Novel metabolic pathways will be discovered, unexpected ecological relationships revealed, and new biotechnological opportunities identified. The hidden 99% is slowly becoming visible, and it's proving to be every bit as diverse and surprising as scientists hoped.

The great plate count anomaly, that century-old observation that most bacteria won't grow on petri dishes, is finally being addressed not by better petri dishes but by fundamentally new approaches to studying microbial life. We're learning to study bacteria on their own terms, in their own environments, using techniques that don't require forcing them into artificial conditions they've never adapted to.

This shift represents more than just methodological innovation. It's a philosophical change in how we approach the study of life itself, recognizing that our traditional tools shaped what we could see and that expanding our toolkit reveals aspects of biology that were always there but remained invisible. The hidden majority of microbial life is hidden no more, and what it's revealing is transforming our understanding of the living world.

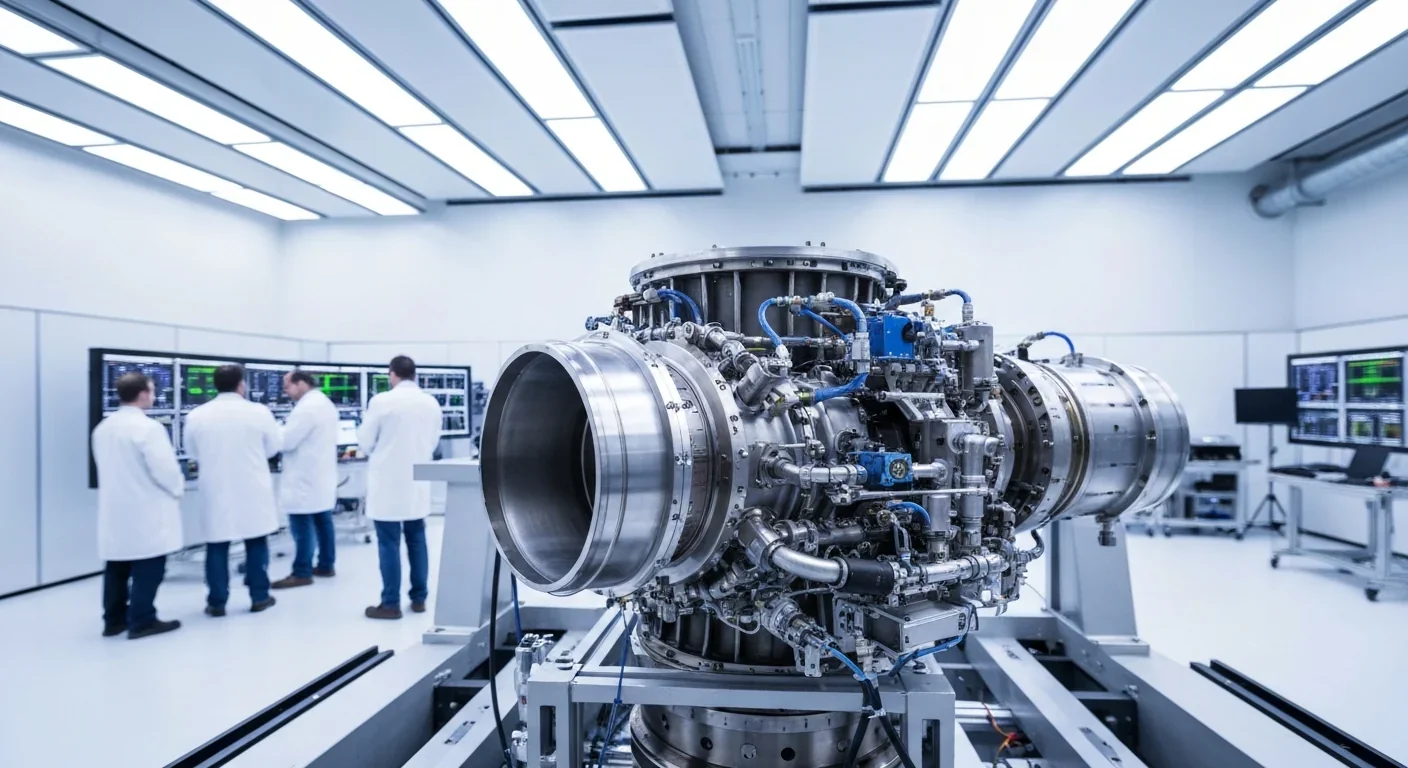

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

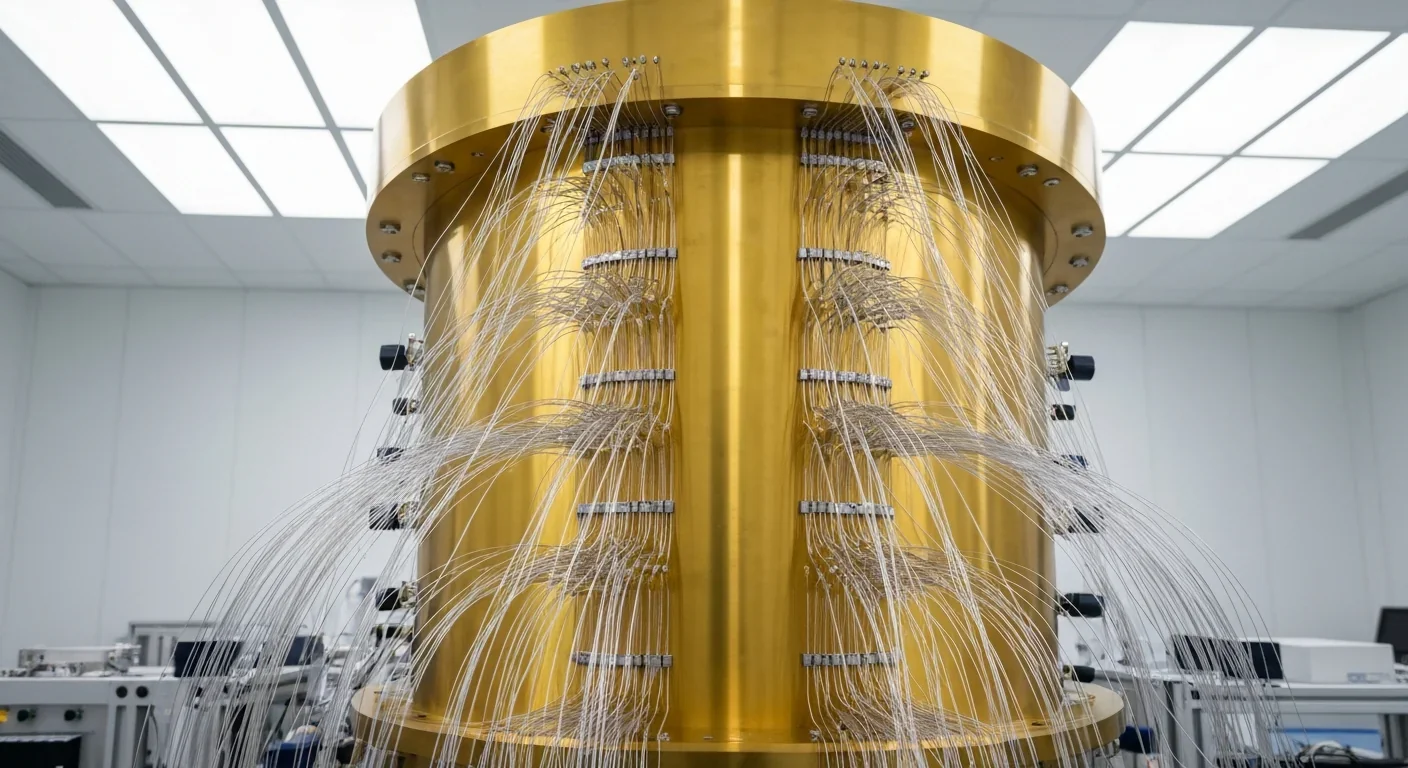

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.