Life Without Sun: Earth's Alien Hydrothermal Vent Worlds

TL;DR: Fungi transport water through microscopic hyphal networks using turgor pressure and cytoplasmic streaming - no heart, no vessels required. Recent discoveries reveal these sophisticated hydraulic systems move water kilometers across forest floors, inspire new engineering approaches, and could revolutionize agriculture and microfluidics.

Beneath your feet right now, a vast network is moving water upward against gravity - no heart, no vessels, no pump. While biologists have understood plant xylem and animal circulatory systems for centuries, fungal hydraulics remained mysterious until recently. In the past two decades, researchers discovered that fungi transport water through microscopic threads using principles that could revolutionize how we design water systems, build materials, and engineer at microscales.

The largest organism on Earth demonstrates this capability spectacularly. A single honey fungus (Armillaria solidipes) in Oregon's Blue Mountains spans over 2,400 acres - its underground network moving water and nutrients across distances that would make a city's water department envious. Scientists now understand that this isn't magic, but physics working at scales and in ways engineers are only beginning to appreciate.

Recent breakthroughs reveal fungi achieve what seemed impossible: they move fluids through networks thinner than a human hair, maintain flow without mechanical pumps, and adapt their transport capacity in real-time based on environmental conditions. The implications stretch from sustainable agriculture to microfluidics, from drought-resistant crops to self-organizing infrastructure.

Unlike plants that pull water up through dead xylem tubes via transpirational tension, fungi use living cells that generate their own internal pressure. Each hyphal cell - the microscopic tubes that form fungal networks - acts as a pressurized compartment, with turgor pressures reaching up to 8 megapascals in some species. That's roughly 1,200 pounds per square inch, enough to penetrate plant cell walls and even some plastics.

This pressure doesn't come from muscular contractions like animal hearts. Instead, fungi concentrate solutes inside their cells through active transport across membranes, creating an osmotic gradient. Water follows, flooding into the cell until the rigid cell wall resists further expansion. The result? A microscopic pressure vessel.

But pressure alone doesn't explain directional flow. The key lies in coordinated pressure gradients across the network. Fungal hyphae create what researchers call source-sink gradients - zones of higher concentration connected to zones of lower concentration. Water and dissolved nutrients flow from source to sink through advective mass flow, the same principle that moves groundwater through aquifers.

Fungal hyphae can generate internal pressures up to 8 megapascals - roughly eight times the pressure in a car tire - enabling them to penetrate solid substrates and transport water upward without any pumping mechanism.

The elegance emerges when you consider scale. A single hyphal network might contain millions of interconnected cells, each maintaining its own turgor pressure while contributing to network-wide gradients. It's distributed hydraulics - no central pump, no master control, yet the system maintains coherent directional flow across meters or even kilometers.

Turgor pressure provides the push, but fungi have another trick: cytoplasmic streaming. Inside each hyphal cell, motor proteins pull the fluid cytoplasm along tracks attached to the cell wall, creating circular currents that can reach speeds of 25 micrometers per second.

Think of it as a cellular conveyor belt. While turgor pressure drives bulk flow between cells, cytoplasmic streaming accelerates transport within cells, creating a hybrid system that combines passive hydraulics with active transport. The result is faster, more efficient nutrient and water distribution than either mechanism alone could achieve.

This two-tier system gives fungi remarkable flexibility. When the network needs rapid response - say, delivering resources to a growing tip encountering a food source - streaming accelerates. When energy is scarce, the fungus can dial back active transport and rely on passive pressure-driven flow. It's adaptive hydraulics that responds to metabolic state and environmental conditions without conscious control.

Recent studies using microfluidic observation platforms have revealed that streaming doesn't just move fluid - it can create localized pressure pulses that propagate through the network like waves. These pulses may coordinate growth, signal resource availability, or even synchronize activities across distant parts of the mycelium.

Structure determines function, and fungal networks showcase evolutionary design principles that engineers are starting to notice. The basic unit - a hypha - measures just 4-6 micrometers in diameter, roughly one-tenth the width of a human hair. At this scale, surface tension and viscous forces dominate over inertia, creating a fluid dynamics regime entirely different from what we experience in pipes and rivers.

The small diameter offers advantages. Capillary action becomes significant, helping draw water into hyphae. Surface-to-volume ratios are enormous, maximizing the area available for membrane transport and osmotic exchange. And most importantly, the rigid chitin cell walls act as pressure-resistant pipes that won't collapse under the internal forces fungi generate.

But individual hyphae face a problem: they're dead ends. Water entering at one end can only move so fast through a single tube. Fungi solve this through network architecture. Hyphae branch repeatedly, creating redundant pathways between any two points. This redundancy provides resilience - if one path fails, flow reroutes through alternate connections - and it allows for parallel transport that dramatically increases total flow capacity.

"The CMN transforms the forest into a network of resource sharing that can direct water and nutrients to those in greatest need, even moving water upward against gravity."

- CU Denver Geography and Environmental Sciences

The most sophisticated fungal networks feature structures called septae - internal walls that divide hyphae into cellular compartments while maintaining connection through central pores. These pores are large enough to allow organelles, nutrients, and water to pass between cells, but can also be dynamically regulated. The barrel-shaped dolipore septa found in basidiomycete fungi even include specialized structures called parenthesomes that may function as valves, controlling flow direction and rate.

Think of it as plumbing with check valves built into every joint. The network can maintain overall pressure while directing flow toward high-demand regions. A growing hyphal tip pushing into new soil? The network redirects resources that way. A drought-stressed region? Flow increases to compensate. All without centralized control - just local responses to pressure and chemical gradients that add up to system-level intelligence.

When plant xylem transports water, it relies on a fundamentally different principle: tension. Transpiration from leaves creates negative pressure that pulls water up from roots through continuous columns in dead xylem vessels. It's elegant, passive, and works spectacularly well - redwoods move water over 100 meters vertically using nothing but evaporation and cohesion.

But it has limitations. Xylem operates under tension, meaning the water columns are constantly at risk of cavitation - bubble formation that breaks the column and stops flow. This makes plants vulnerable to drought, freeze-thaw cycles, and mechanical damage. And because xylem tissue is dead, it can't respond actively to changing conditions or repair itself when damaged.

Fungal systems operate under positive pressure, eliminating cavitation risk. Living hyphal cells can sense their environment, adjust osmotic concentrations, and even regrow damaged sections. The trade-off? Energy cost. Maintaining high turgor pressure requires constant metabolic work, while plant transpiration is essentially free once the tissue is built.

Animal circulatory systems use a third approach: central pumps pushing fluid through closed networks of vessels. Hearts generate enormous pressure pulses that propagate through elastic arteries, with one-way valves ensuring directional flow. It's effective but requires complex organs, precise timing, and significant energy expenditure.

Fungi split the difference. Distributed pressure generation means no single point of failure, and metabolic cost scales with network size since every cell contributes. There's no need for elastic vessels or synchronized contractions - just millions of cells each doing their part maintains system-wide flow. For an organism that might span acres with no centralized nervous system, it's the perfect solution.

The hydraulic capabilities of fungi become especially important in mycorrhizal associations - symbiotic partnerships where fungal hyphae colonize plant roots. These partnerships are ubiquitous; over 90% of land plants form mycorrhizae. And one of the most valuable services fungi provide? Water transport.

Mycorrhizal fungi can deliver up to 40% of a plant's water requirements, accessing soil micropores that root hairs can't reach. Fungal hyphae, far thinner than the finest roots, penetrate tiny soil spaces and extract water at potentials below -1.5 megapascals - conditions where roots would fail. The fungi then transport this water through their hyphal networks and transfer it directly into plant roots via specialized interfaces called Hartig nets in ectomycorrhizae or arbuscules in arbuscular mycorrhizae.

Over 90% of land plants depend on mycorrhizal partnerships, with fungi delivering up to 40% of plant water needs by accessing soil micropores that roots can't reach.

But the real magic happens at the network level. A single fungal mycelium can connect multiple plants - sometimes dozens of different species - creating what researchers call common mycelial networks. These networks enable hydraulic redistribution: water movement from wet to dry soil zones mediated by fungal hyphae bridging between plant root systems.

A 2025 study demonstrated this directly using dark septate endophytes and dye-tracing experiments. Researchers grew two plants in separate pots connected only by fungal hyphae crossing an air gap. When they fed dye-marked water to one plant, it appeared hours later in the leaves of the neighboring plant - transported entirely through the fungal bridge.

This means forests aren't collections of individual trees competing for water; they're hydraulically connected communities. During drought, deeply rooted trees that can still access groundwater essentially share it with shallower-rooted neighbors via fungal intermediaries. Seedlings that haven't established deep roots survive by tapping into the network. Plants don't just tolerate their fungal partners - they depend on them for hydraulic resilience.

Fungal hydraulic networks don't operate in isolation - they respond dynamically to their environment in ways that reveal sophisticated adaptation. Soil moisture, temperature, nutrient availability, and even the presence of other organisms all influence how fungi transport water.

During drought, you might expect fungal networks to shut down as soil dries. Instead, mycorrhizal connections often intensify. Research shows that plants under water stress allocate more carbon to their fungal partners, and the fungi respond by expanding hyphal networks deeper into soil, searching for remaining water reserves. This investment pays off - plants connected to extensive fungal networks show significantly better survival during drought than isolated plants.

Temperature affects both the biophysical properties of water and the metabolic activity of fungal cells. Colder temperatures increase water viscosity, making it harder to pump through narrow hyphae. But fungi that remain active in cold soils compensate by adjusting osmotic concentrations, maintaining sufficient turgor pressure to sustain flow even as physics works against them.

The composition of the fungal and plant community also matters. Different fungal species have different hydraulic capacities. Ectomycorrhizal fungi, which form sheaths around root tips and penetrate between root cells, generally move more water than arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, which penetrate into root cells. And within each group, species vary enormously in hyphal thickness, branching patterns, and metabolic strategies.

"Hyphae in ectomycorrhizal networks can transport water across distances exceeding several meters and, because of their interconnectedness, maintain hydraulic continuity during soil drought."

- CU Denver Geography and Environmental Sciences

Even the time of day influences fungal water transport. At night, when plants close stomata and reduce transpiration, root pressure increases. This positive pressure can actually reverse the normal direction of water flow, pushing water from roots back into soil - a process called hydraulic redistribution. Fungal hyphae facilitate this nighttime redistribution, moving water from deep, moist soil layers accessed by some roots to dry, shallow layers where other plants need it most.

The past five years brought breakthroughs that fundamentally changed how scientists understand fungal hydraulics. Researchers developed microfluidic chambers that allow real-time observation of fungal growth and transport under controlled conditions. These platforms revealed behaviors impossible to detect in field studies or traditional lab cultures.

One surprise: fungi don't just passively respond to existing water gradients - they create them. By selectively transporting solutes to growing tips or resource-rich zones, fungi establish osmotic gradients that then drive bulk water flow. It's not merely reactive hydraulics; it's engineered flow that the organism controls through metabolic activity and architectural growth.

Another discovery involved electrical signaling. Fungal networks propagate electrical potential spikes that may coordinate activities across the mycelium. Some researchers hypothesize these signals regulate hydraulic transport by triggering changes in membrane permeability or septal pore opening. If confirmed, it would mean fungal networks possess a primitive sensing and control system for their hydraulic infrastructure - something like a nervous system for water management.

Isotope-labeling experiments provided the clearest evidence yet of network-scale water transport. By feeding plants water enriched with deuterium or oxygen-18, researchers could trace exactly where that water went. The results showed that mycorrhizal networks move water between plants separated by several meters within hours - far faster than soil moisture diffusion alone could account for. The fungal network acts as a hydraulic shortcut, creating effective connectivity that soil structure can't provide.

And perhaps most intriguingly, studies of the largest known organism - that Oregon honey fungus - revealed that it maintains hydraulic continuity across its entire 2,400-acre extent. Genetic analysis confirmed it's a single individual, and isotope studies showed water and nutrients moving between sections miles apart. The implications for understanding biological transport limits are staggering. If a single organism can move fluids across kilometers using only microscopic tubes and turgor pressure, what other scale barriers might be overcome with the right design principles?

Engineers are taking notice. Fungal hydraulic systems demonstrate solutions to problems that plague human-designed systems: how to move fluids through narrow channels, how to create resilient networks without central pumps, how to adapt transport capacity to local demand, and how to self-repair when damaged.

Microfluidic devices - tiny lab-on-a-chip systems that manipulate minute fluid volumes - currently rely on external pumps and valves. Imagine instead a self-organizing microfluidic network that generates its own pressure differentials through osmotic control and routes flow through architectural branching patterns. Such a system could be simpler, more robust, and capable of autonomous adaptation to changing conditions.

Materials engineers see potential in the pressure-resistant structures fungi build. Hyphal cell walls contain chitin, the same polymer that forms insect exoskeletons, arranged in crystalline fibers embedded in a matrix of proteins and glucans. This composite material is strong, light, and biodegradable. Synthetic materials mimicking this architecture could create pressure vessels, reinforcing fibers, or structural elements that combine strength with environmental sustainability.

Mycorrhizal inoculation can reduce crop irrigation requirements by up to 25%, potentially offering a nature-based solution as climate change intensifies agricultural water scarcity.

Water management for agriculture faces enormous challenges as climate change increases drought frequency and irrigation demands strain aquifers. Mycorrhizal inoculation - introducing beneficial fungi to crop systems - shows promise for improving water-use efficiency. Some studies report up to 25% reduction in irrigation requirements for mycorrhizal crops. As growers face water restrictions, fungal partnerships may shift from interesting biology to agricultural necessity.

Urban infrastructure could borrow principles from mycelial architecture. Current water distribution systems use rigid, hierarchical networks of pipes that fail catastrophically when broken and waste water through leaks. A mycelial-inspired design might feature redundant pathways, self-healing materials, and distributed pressure generation that maintains flow even when individual components fail. Some architects are already experimenting with living fungal materials that grow into structural forms, including potentially water-transporting networks embedded in building walls.

At the most speculative end, researchers imagine soft robots that use osmotic pressure for actuation, mimicking how fungi move and grow through turgor pressure changes. Or self-organizing sensor networks that route signals like fungi route nutrients, adapting network structure to communication demands. The principles are universal - distributed control, redundant pathways, local responses creating global function - and they apply far beyond hydraulics.

Despite recent progress, fundamental questions remain. Scientists still can't predict exactly how much water a given fungal network will transport under specific conditions. The relationships between hyphal architecture, environmental factors, and transport capacity are understood qualitatively but not quantitatively. Developing predictive models would enable agricultural applications and help ecologists understand forest water cycling.

The role of electrical signaling in regulating transport remains controversial. While researchers have documented electrical impulses propagating through fungal networks and observed correlations with growth and transport patterns, the mechanisms connecting electrical activity to hydraulic control aren't clear. Do electrical signals directly control membrane transporters or septal pores? Or are both signals and transport changes independent responses to some third factor?

Understanding how fungi manage transport over truly large spatial scales requires better field methods. Most studies occur in labs or small field plots, but the Oregon honey fungus and other massive individuals suggest that fungi can coordinate activity across kilometers. How do they maintain network integrity? How do they prevent hydraulic isolation of distant sections? What limits network size?

The diversity of fungal hydraulic strategies remains largely unexplored. Most research focuses on a handful of model species or economically important mycorrhizal fungi. But there are hundreds of thousands of fungal species, likely with tremendous variation in hydraulic capabilities. Comparative studies could reveal whether current understanding captures general principles or whether we're missing entire categories of transport mechanisms.

And the big question for applied research: can we reliably manipulate fungal networks to solve human problems? Mycorrhizal inoculation works in some contexts but fails in others for reasons not fully understood. Engineering living fungal infrastructure requires controlling growth, maintaining viability, and ensuring the fungal partners actually do what we want. Living systems are notoriously difficult to engineer, but the potential payoff - self-growing, self-repairing, biodegradable materials and infrastructure - makes it worth trying.

Every forest floor, every agricultural field, every yard hosts these hydraulic networks, silently moving water through channels finer than spider silk. We've walked over them forever without knowing the sophisticated fluid dynamics occurring inches below our feet.

The recognition that fungi represent a legitimate hydraulic system - comparable in importance to plant xylem or animal circulatory systems - changes ecology, agriculture, and potentially engineering. It adds a third kingdom to the pantheon of biological fluid transport, with unique mechanisms and capabilities that complement and sometimes exceed what plants and animals accomplish.

From an evolutionary perspective, fungi solving the water transport problem differently makes sense. Without the ability to create rigid xylem vessels through programmed cell death, and without the capacity for muscular pumping, fungi had to find another path. Distributed pressure generation and adaptive network architecture emerged as that solution, one that proved so effective that fungi colonized virtually every terrestrial habitat and now form partnerships with the majority of land plants.

But calling it a solution implies the problem is solved, and that's not quite right. Fungal hydraulics remains an active area of evolution. Species continue to adapt their transport mechanisms to new environments and challenges. The networks connecting plants and facilitating water redistribution are dynamic ecological processes, not fixed infrastructure. Climate change, habitat fragmentation, and agricultural intensification all affect these systems in ways we're only beginning to understand.

The practical question is what we do with this knowledge. Do we incorporate fungal networks into how we manage forests and farms, acknowledging their role and working to support rather than disrupt them? Do we push biomimicry forward and build genuinely new technologies inspired by hyphal hydraulics? Or do we catalog these insights and move on, treating them as interesting biology but ultimately peripheral to human concerns?

Given the challenges ahead - water scarcity, agricultural intensification, need for sustainable materials - it seems increasingly likely that fungal hydraulics will shift from academic curiosity to practical necessity. Engineers are already working on the first fungal-inspired systems. Farmers are experimenting with mycorrhizal management. Materials scientists are growing fungal composites.

The network beneath your feet isn't just moving water for itself - it might be showing us how to move water for ourselves, better than we've managed so far. No heart, no vessels, just millions of tiny cells working together, generating pressure, creating gradients, and moving fluids exactly where they need to go. That's not primitive - that's sophisticated. And it might just be the future of hydraulics, grown from the ground up.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

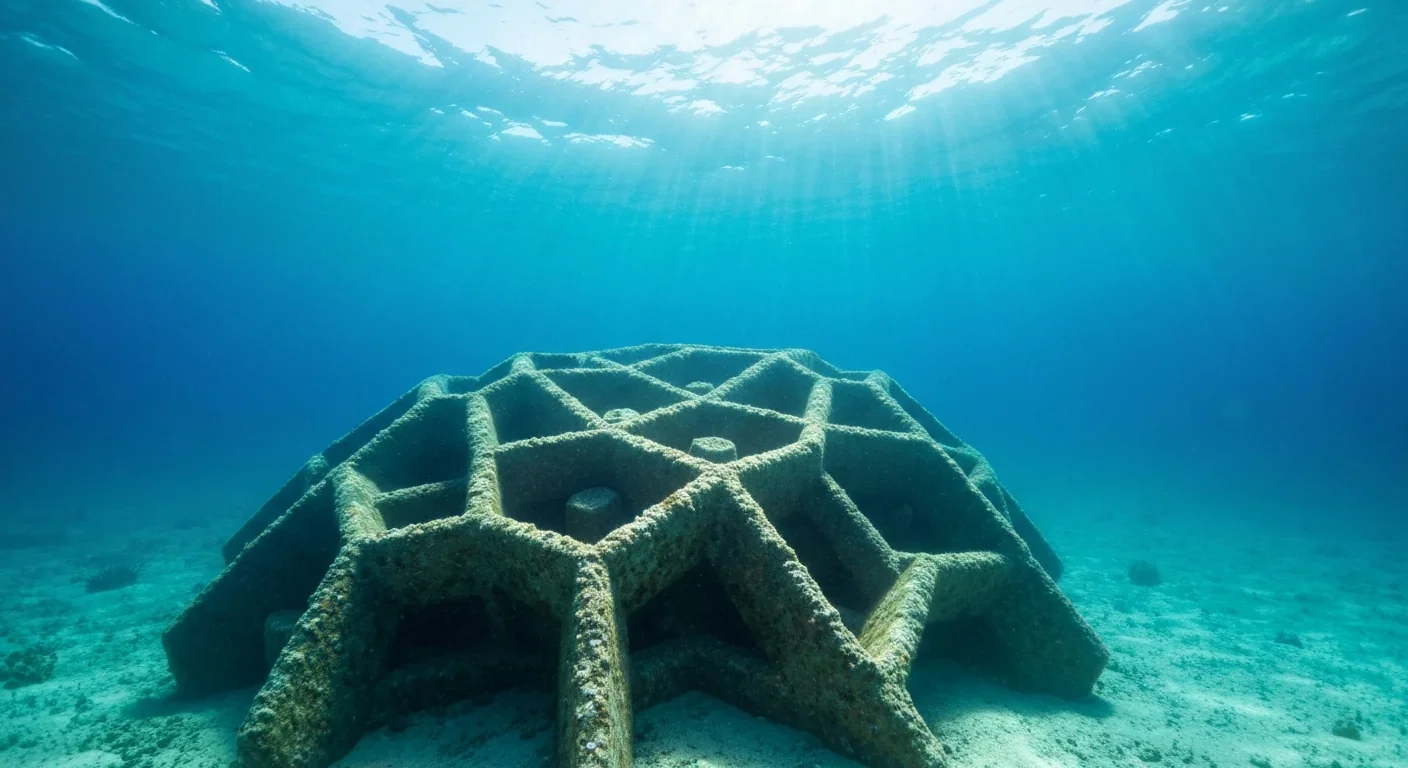

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

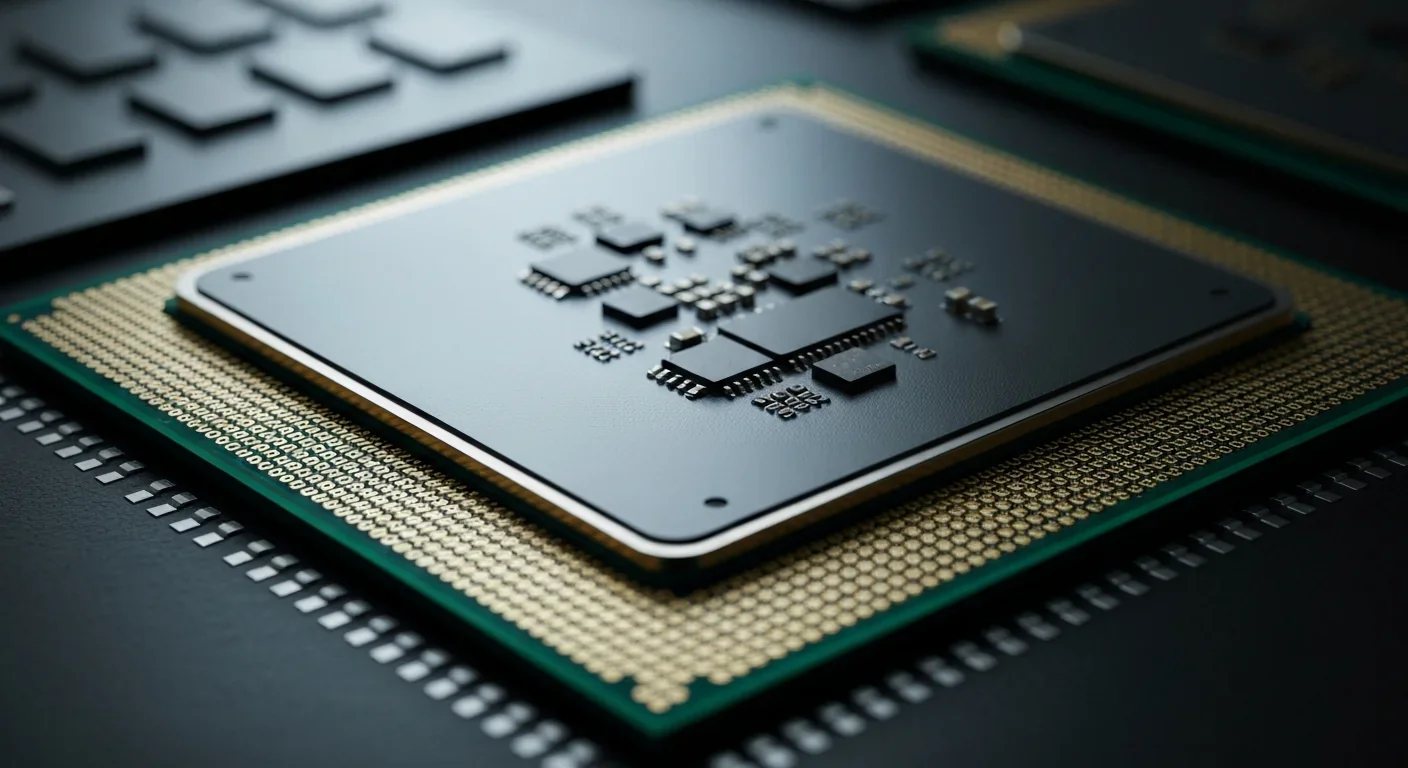

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.