Nature's First Farmers: 50 Million Years of Ant Agriculture

TL;DR: Electric fish evolved one of nature's most sophisticated sensory systems multiple times independently. Driven by the challenges of hunting in murky waters, these species developed electroreception and electric organs through an evolutionary arms race that continues to reveal insights into sensory evolution, neurobiology, and biological innovation.

Imagine hunting in complete darkness. No light, no sound to guide you - just the faint electrical whispers of a heartbeat somewhere in the murky water. This isn't science fiction. It's Tuesday for a shark. While humans fumble for light switches in darkened rooms, countless fish species navigate, hunt, and communicate using a sensory system so alien to our experience that scientists didn't even confirm its existence until the 20th century. Electroreception represents one of evolution's most remarkable innovations, a biological technology that emerged independently multiple times across different lineages, driven by the unforgiving demands of survival in environments where eyes become useless.

The story of electric fish reveals more than just a curious adaptation. It demonstrates how environmental pressure sculpts biology with ruthless precision, how predators and prey engage in escalating sensory warfare, and how the same evolutionary challenges produce strikingly similar solutions across vastly different species. From the muddy rivers of the Amazon to the depths of the ocean floor, electroreception has transformed the rules of engagement for hundreds of species.

Water carries electricity far better than air - about 800 times better, in fact. Every living creature generates electrical fields through the simple act of being alive: muscle contractions, heartbeats, and neural activity all produce measurable electrical signals. In clear water with good visibility, this matters little. Vision dominates. But descend into the sediment-choked rivers of tropical regions, venture into the lightless abyssal zones of the ocean, or hunt at night along a murky coastline, and suddenly electricity becomes the most reliable source of information available.

This created an evolutionary opening. Any fish that could detect these electrical signatures would gain an enormous advantage in low-visibility environments. They could find prey hiding beneath sand, navigate through pitch-black water, or detect approaching predators. The pressure to develop this capability was immense, and evolution responded - repeatedly.

Scientists now know that electroreception evolved independently at least six times across different groups of fish. Sharks and rays developed it. Catfish developed it. Knifefish developed it. The fact that evolution kept reinventing this solution tells us something profound about the selective pressures these animals faced. When the benefits are substantial enough, biology finds a way.

Electroreception evolved independently at least six times across different fish groups - proof that when environmental pressure is strong enough, evolution will repeatedly find the same solution.

The evolutionary journey to electroreception didn't start from scratch. Fish already possessed a sophisticated sensory system called the lateral line - a series of mechanoreceptors running along their bodies that detect water movement and vibration. These hair-cell receptors, similar to those in our inner ears, respond to mechanical pressure.

At some point in the distant past, likely in a common fish ancestor, some of these mechanoreceptors began responding to electrical fields instead. The transformation required relatively modest changes: the hair cells needed to become more sensitive to ionic currents, and the neural circuitry needed to interpret these signals differently. Based on which cranial nerves connect to the lateral line and electroreceptors, scientists hypothesize that electroreception first emerged in an ancient common ancestor, then was lost and regained multiple times as different lineages faced different environmental challenges.

In 1678, Italian physician Stefano Lorenzini made a discovery while dissecting a torpedo ray that would eventually unlock this mystery. He described gel-filled elongated pores in the skin, now called ampullae of Lorenzini. These structures act as conductive jelly channels to hair-cell receptors, essentially functioning as biological voltmeters. Sharks possess thousands of these ampullae concentrated around their heads, giving them exquisite electrical sensitivity.

The sensitivity is staggering. Sharks can detect electrical fields as weak as five billionths of a volt per centimeter - sensitive enough to detect the beating heart of a flounder buried under sand from several feet away. When researchers placed electrodes generating weak electric fields near dead fish, sharks attempted to eat the electrodes. This same sensitivity explains why sharks sometimes bite underwater cables, including transoceanic internet cables that provide global connectivity. To a shark, these cables produce electrical signatures that mimic prey.

Detecting electricity proved so useful that some fish took the next logical step: generating it themselves. If you can sense electrical fields, why not create your own to illuminate your surroundings, communicate with others, or stun prey?

This led to the evolution of electric organs - specialized structures derived from modified muscle or nerve cells called electrocytes. These cells act like biological batteries stacked in series, each producing a small voltage that adds up when thousands fire simultaneously. The result ranges from the gentle pulses of weakly electric fish to the shocking 860-volt discharge of the electric eel.

Weakly electric fish, which include the diverse mormyrid elephantfish of Africa and the gymnotiform knifefishes of South America, generate continuous electric fields around their bodies. They monitor distortions in these self-generated fields to create a three-dimensional electrical image of their surroundings - a process called active electroreception. Objects with different electrical conductivity distort the field in characteristic ways, allowing the fish to distinguish between rocks, plants, prey, and other fish.

"The sophistication of electric fish sensory systems rivals echolocation in bats and dolphins. Just as bats can distinguish different insect species by analyzing echoes, electric fish can identify objects by their electrical signatures."

- Dr. Chris Braun, Hunter College

The sophistication here rivals echolocation in bats and dolphins. Just as bats can distinguish different insect species by analyzing the echoes of their ultrasonic calls, electric fish can identify objects by their electrical signatures. Some species can even filter out their own electrical emissions to focus on external signals - essentially subtracting their own voice from the conversation to hear others more clearly.

Strongly electric fish took a different path. The electric catfish of the Nile can produce 350-volt shocks. Electric eels, despite their name actually a type of knifefish, can generate repeated 860-volt pulses - enough to stun a horse. These high-voltage discharges serve both as weapons and as defense mechanisms, demonstrating how the same biological technology can be scaled for different purposes.

The evolution of electroreception and electrogeneration created a classic evolutionary arms race. Predators developed better detection capabilities. Prey responded by reducing their electrical signatures or developing jamming techniques. Predators countered with even more sensitive receptors. The cycle continued, driving both sides toward greater sophistication.

Electric fish face a particular challenge: their own electric organs make them highly visible to any predator with electroreception. It's like being a spy who must constantly transmit radio signals - you're advertising your presence to anyone listening. This created pressure for diversification.

Different species evolved distinctive electrical signatures - varying in frequency, waveform, and pulse pattern - essentially creating electrical dialects. In waters where multiple electric fish species coexist, these differences allow individuals to identify their own species and avoid interfering with each other's signals. Some species can even modulate their signals dynamically to avoid jamming, a behavior called the jamming avoidance response.

The African elephantfish provides a striking example. These fish generate electrical pulses at species-specific frequencies ranging from 80 to over 1,000 Hz. When two elephantfish with similar frequencies approach each other, both automatically shift their frequencies away from each other to maintain clear communication channels. This sophisticated signal processing happens automatically in their specialized brain regions dedicated to electroreception.

Research on weakly electric fish has revealed that hormones and social context can modulate electrical signals. Male and female fish of the same species often produce sexually dimorphic electrical patterns, allowing for electrical courtship displays. These signals carry information about individual identity, health, and reproductive status - a completely silent, invisible communication system operating beneath the surface.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of electroreception is how many times evolution independently invented it. The Mormyridae elephantfish of Africa and the Gymnotiformes knifefishes of South America are only distantly related, yet both groups independently evolved nearly identical electrogeneration and electroreception systems. This represents a textbook example of convergent evolution - when similar environmental pressures produce similar adaptations in unrelated lineages.

Both groups inhabit turbid tropical rivers where vision provides limited utility. Both are nocturnal. Both face the challenge of finding small invertebrate prey in dark, murky water. And both evolved the same solution: generate weak electric fields and monitor the distortions. The fact that both groups evolved such similar systems despite being separated by ocean and evolutionary history for millions of years demonstrates the power of natural selection to find optimal solutions to environmental challenges.

African elephantfish and South American knifefishes independently evolved nearly identical electroreception systems despite being separated by millions of years and an ocean - a stunning example of convergent evolution.

Even more remarkably, electroreception has re-evolved at least twice in lineages that previously had it and lost it. Sensory systems require significant energy investment, so when environmental conditions change and a sense becomes less useful, evolution often eliminates it. At some point, the ancestors of modern knifefish and catfish lost their electroreception. Later, when their descendants returned to environments where it provided advantages, they redeveloped it.

This cycle of loss and regain demonstrates that evolution isn't a linear march toward greater complexity. It's an opportunistic process that adds or removes features based on their current utility. The genetic machinery for building electroreceptors apparently remains latent in fish genomes, ready to be reactivated when selective pressure favors it.

Beyond fish, electroreception has evolved in some truly unexpected animals. The platypus, an egg-laying mammal from Australia, possesses electroreceptors in its bill that allow it to hunt shrimp and other prey in murky rivers. Dolphins may have rudimentary electroreception. Even some amphibians possess passive electroreception. Each instance represents another independent invention of the same fundamental technology.

Understanding how fish brains process electrical information has revealed unexpected complexity. Electroreceptive fish dedicate significant brain real estate to analyzing electrical signals - in some species, the cerebellum-like structures involved in electroreception are larger than the rest of the brain combined.

This makes evolutionary sense. Vision in humans occupies about 30% of our cerebral cortex. Our brains are essentially visual processing machines wrapped around a few other functions. Similarly, for elephantfish and knifefishes, electrical sense dominates neural architecture. Their brains evolved specialized circuits for filtering signals, detecting temporal patterns, comparing inputs across different receptors, and extracting meaning from electrical noise.

The most sophisticated electric fish can distinguish different materials by their electrical conductivity, estimate distances to objects based on field distortion, track multiple moving targets simultaneously, and communicate complex information through electrical signals. Some researchers have compared this to a biological version of radar or sonar, but that undersells it. Electric fish are processing sensory information from a modality humans cannot perceive, creating mental representations of a world we can barely imagine.

Recent genomic research has revealed the molecular basis for convergent evolution of electric organs. Despite evolving independently, African and South American electric fish use remarkably similar genetic pathways to build their electric organs. The same sodium channel genes get repurposed for electrogeneration. The same developmental programs get deployed. This suggests there are limited ways to build biological batteries - evolution found the optimal solution and converged on it repeatedly.

Scientists study electric fish not just for curiosity but for insights into neural computation, sensory processing, and brain evolution. Understanding how these fish filter electrical noise, process temporal patterns, and generate real-time sensory maps could inform everything from prosthetic design to robot navigation systems. The principles these animals use to make sense of their electrical world might prove useful as we design machines that must operate in challenging sensory environments.

The evolutionary arms race that drove electroreception's sophistication unfolded over millions of years in relatively stable aquatic environments. But human activity is changing those environments faster than evolution can respond.

Turbidity - the murkiness that made electroreception advantageous - is changing in many rivers. Agricultural runoff, deforestation, and dam construction alter sedimentation patterns. Some rivers grow murkier; others grow clearer. Changes in turbidity affect how fish use different sensory modalities. Fish that evolved to rely heavily on electroreception in murky water may find their habitats becoming either too clear (making them vulnerable to visual predators) or too polluted (interfering with electrical sensitivity).

Electrical pollution presents another challenge. Human-generated electromagnetic fields from power lines, underwater cables, and electronic devices create noise that can interfere with fish that rely on detecting weak biological electrical fields. For predators like sharks and rays that detect prey by their electrical signatures, anthropogenic electrical noise might be like trying to have a conversation next to a jet engine.

"Habitat destruction threatens many electroreceptive species before we fully understand the diversity of electroreception systems that evolution has produced. Many species have restricted ranges, sometimes limited to individual river tributaries."

- Conservation Biology Research

Habitat destruction threatens many electroreceptive species directly. The Amazon and Congo river basins - hotspots of electric fish diversity - face pressure from deforestation, dam construction, and climate change. Many electric fish species have restricted ranges, sometimes limited to specific river systems or even individual tributaries. Habitat loss could drive extinctions before we fully understand the diversity of electroreception systems that evolution has produced.

Conservation efforts face the challenge that many electric fish species remain poorly studied. Scientists have only begun to catalog the diversity of electrical signals, communication systems, and ecological relationships. Some species were discovered only recently; others likely await discovery. The urgency here mirrors what conservationists face with many tropical species: protect habitats before we lose biological innovations we haven't yet documented.

The evolution of electroreception offers lessons that extend far beyond fish biology. It demonstrates how environmental challenges drive sensory innovation, how evolution can repeatedly converge on similar solutions, and how sophisticated biological systems can emerge from relatively simple modifications to existing structures.

For neuroscientists, electric fish provide natural experiments in brain evolution and sensory processing. For engineers, they offer existence proofs that biological electrical sensing can achieve extraordinary sensitivity and sophistication. For evolutionary biologists, they illustrate how selective pressure shapes complex adaptations and how contingency and constraint interact to determine evolutionary outcomes.

The comparison to other sensory modalities proves instructive. Echolocation in bats and dolphins represents another example of a sophisticated sensory system that evolved independently multiple times in response to similar challenges - in that case, navigating and hunting in darkness. Electroreception and echolocation both demonstrate that when the selective advantage is strong enough, evolution will find ways to access previously untapped sensory information.

Human technology has developed its own versions of these biological innovations. We use sonar for underwater navigation, radar for tracking objects through clouds, and electromagnetic sensors for applications from metal detection to medical imaging. Yet in many ways, our artificial systems still can't match the sophistication, miniaturization, or energy efficiency of biological sensory systems honed by millions of years of evolution.

Despite decades of research, electric fish continue to surprise scientists. Recent discoveries include new species with unique electrical signatures, unexpected social behaviors mediated by electrical communication, and sophisticated signal processing strategies that rival engineered systems.

The Peters's elephantnose fish, for example, can detect tiny changes in electrical conductivity that allow it to distinguish between different types of prey. It processes this information using a brain that, relative to body size, rivals that of humans. Understanding how such a small brain achieves such sophisticated processing could inform efforts to build more efficient artificial intelligence systems.

Researchers are also investigating how electric fish might serve as indicator species for ecosystem health. Because these animals are sensitive to changes in water conductivity, turbidity, and electromagnetic interference, their populations might provide early warning signs of environmental degradation. Monitoring the diversity and abundance of electric fish communities could help track the health of tropical river systems.

The genomic revolution has opened new avenues for understanding electroreception's evolution. By comparing genomes across species with and without electroreception, scientists can identify the specific genetic changes that enable this sense. This could reveal general principles about how complex traits evolve and how existing biological structures get repurposed for new functions.

Climate change adds another dimension to the story. As temperatures rise and precipitation patterns shift, the aquatic environments that electric fish inhabit will change. Will these species adapt? Migrate? Decline? The same evolutionary flexibility that allowed electroreception to evolve multiple times might help these fish respond to rapid environmental change - or the pace of change might exceed evolution's capacity to adapt.

The next time you're fumbling in the dark, consider the electric fish. They don't fear the darkness - they own it. Through millions of years of evolutionary refinement, these animals have developed a sensory modality so alien to human experience that we struggled for centuries to even confirm it existed.

Their story reveals how life adapts to environmental challenges with solutions that often surpass human engineering in sophistication and efficiency. It shows how the same problem - navigating and hunting in darkness - can drive the independent evolution of similar solutions across vastly different lineages. And it demonstrates that Earth's sensory diversity extends far beyond what we directly experience.

As we face environmental changes that may threaten these remarkable animals, we're confronted with a troubling irony. The evolutionary arms race that produced electroreception unfolded over geological time, allowing for gradual refinement and diversification. The threats these animals now face - habitat destruction, pollution, climate change - operate on timescales measured in decades, far too fast for evolution to mount an effective response.

Understanding and protecting electric fish means preserving not just species but entire evolutionary innovations - biological technologies millions of years in the making that we've barely begun to understand. In the murky waters where they evolved their electrical superpowers, these fish still navigate, hunt, and communicate using senses we cannot perceive, reminding us that nature's solutions to life's challenges often exceed our imagination.

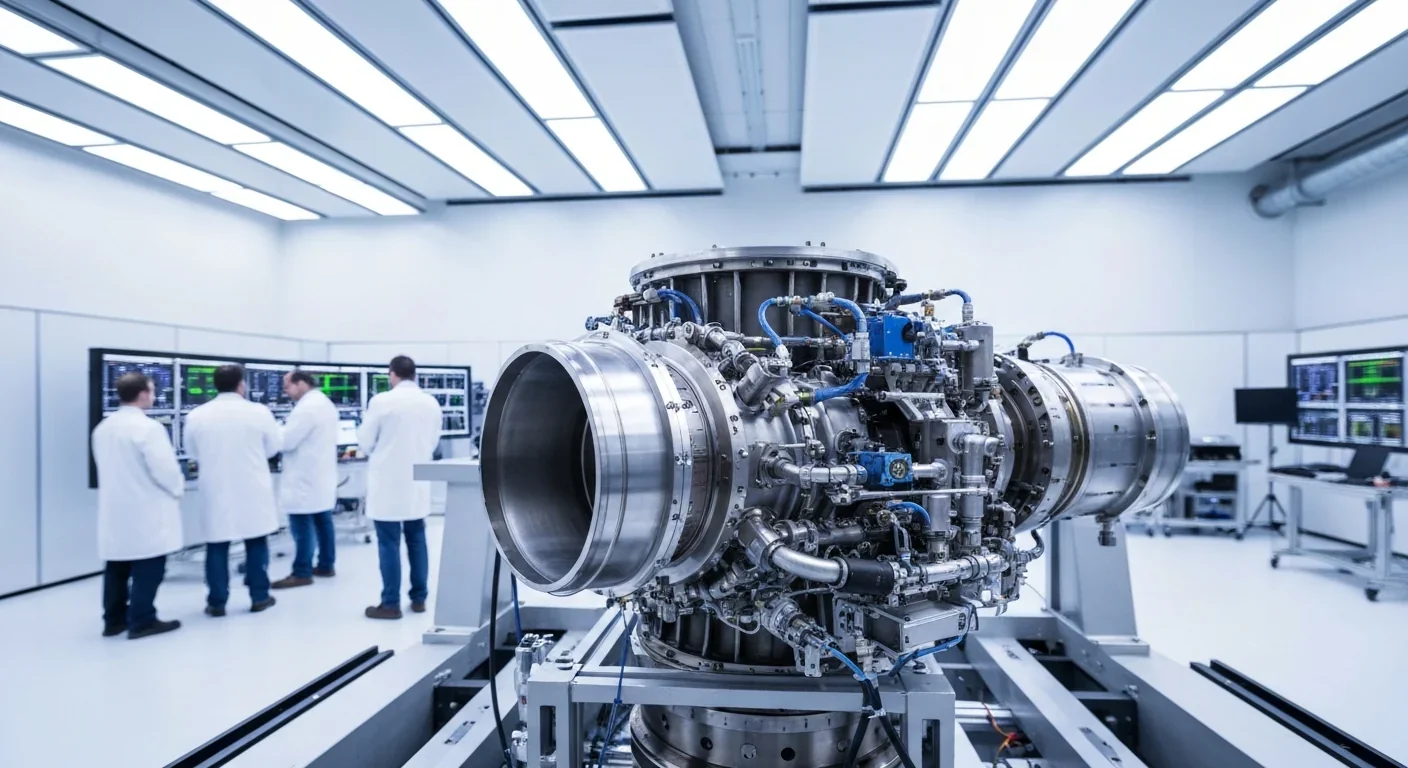

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

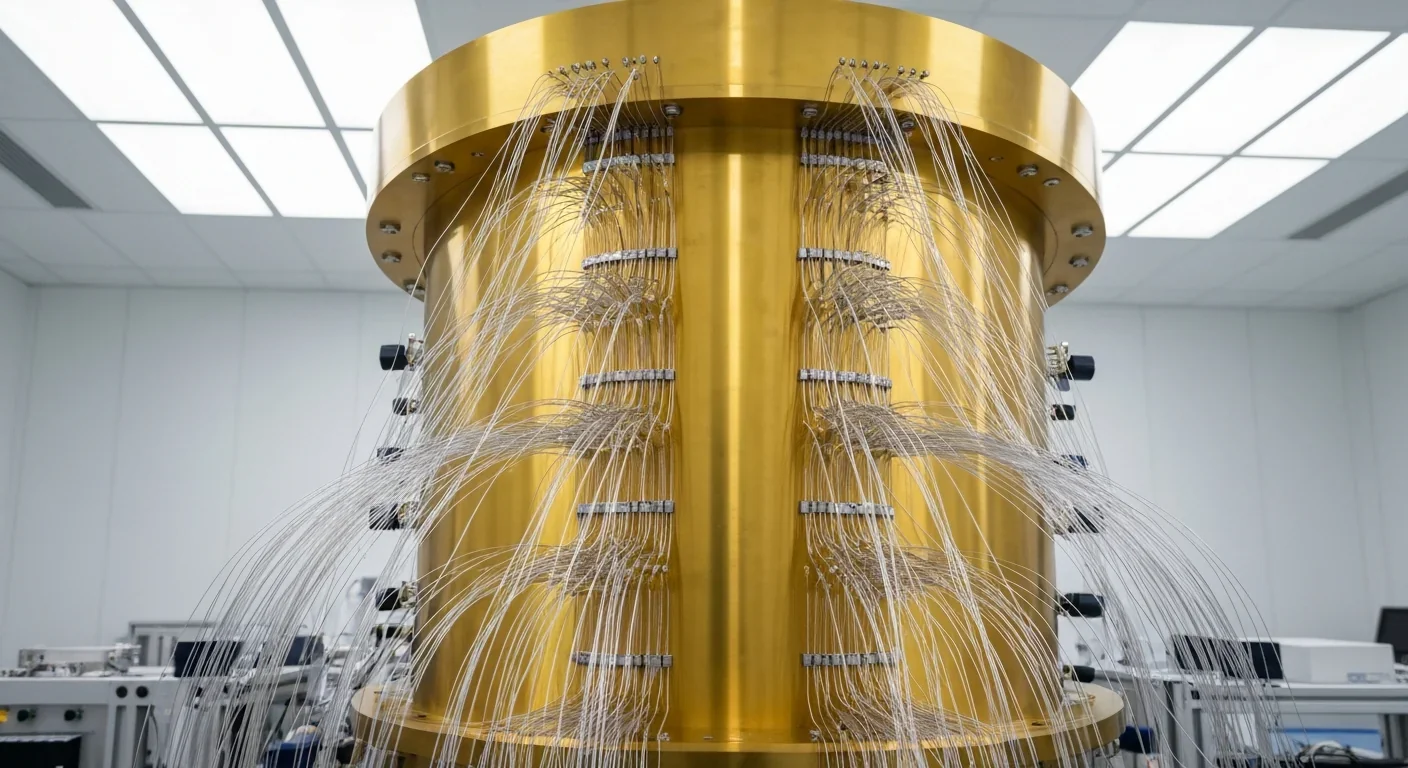

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.