Nature's First Farmers: 50 Million Years of Ant Agriculture

TL;DR: Deep-sea creatures use bioluminescence as a sophisticated communication system, with 90% of species producing light through chemical reactions. From mating displays to predator warnings, these organisms have evolved complex light-based signals in Earth's darkest realm.

More than a kilometer beneath the ocean's surface, where sunlight becomes a distant memory and pressure would crush a human instantly, something extraordinary happens. In this pitch-black void, creatures are talking to each other, flirting, hunting, and coordinating their movements - all through flashes of living light. Recent discoveries reveal that up to 90% of deep-sea species have evolved bioluminescence, making the ocean's darkest depths one of the most illuminated ecosystems on Earth.

This isn't random flickering. Scientists are now realizing that bioluminescent signals represent a sophisticated communication system as complex as bird songs or whale calls, but adapted for an environment where sound travels too slowly and scent disperses unpredictably. The implications stretch beyond marine biology - these discoveries are reshaping our understanding of how intelligence and communication evolve in extreme environments, with potential applications for everything from underwater robotics to searching for life on other worlds.

The fundamental mechanism behind bioluminescence is surprisingly elegant. Deep-sea organisms produce light by oxidizing a molecule called luciferin in a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme luciferase. When luciferin combines with oxygen in the presence of luciferase, it releases energy in the form of photons - visible light with virtually no heat, making it one of nature's most efficient light sources.

What makes this remarkable is the diversity of luciferin molecules that have evolved independently across different species. Approximately 76% of major deep-sea taxa have developed this capability, but they didn't all inherit it from a common ancestor. Instead, bioluminescence has evolved at least 40 separate times throughout Earth's history, with different organisms developing unique chemical pathways to achieve the same glowing result.

Bioluminescence has evolved independently at least 40 times in Earth's history - making it one of evolution's most successful solutions to life in darkness.

Some creatures manufacture their own light-producing chemicals, while others take a different approach entirely. The deep-sea anglerfish, for instance, doesn't produce light through its own biochemistry. Instead, it cultivates colonies of bioluminescent bacteria in a specialized organ called an esca - that iconic dangling lure that hangs in front of its massive jaws. These bacteria live symbiotically with the fish, receiving shelter and nutrients while providing illumination on demand.

Research published in 2019 revealed something unexpected about this relationship. Scientists discovered that anglerfish bacteria most likely come from the water rather than being passed from parent to offspring. The bacteria have undergone genomic reduction, losing genes necessary for independent survival, suggesting they're obligately dependent on their host. Yet preliminary data indicates the fish may release bacteria back into the environment once populations grow too large, possibly ensuring future generations can acquire their luminous partners.

This represents what researchers call a "third type" of symbiosis - not quite permanent inheritance, not quite temporary association, but somewhere in between. It's a discovery that challenges traditional categories and suggests the deep sea harbors biological relationships we're only beginning to understand.

If the chemistry of bioluminescence is impressive, the anatomical structures that control it are downright astounding. Photophores - specialized light-emitting organs - range from simple glandular cells to structures as complex as the human eye, complete with lenses, color filters, shutters, and reflectors.

Consider the flashlight fish, which carries what amounts to biological headlamps beneath each eye. These oval-shaped photophores emit bright blue light that can attract zooplankton from considerable distances. But here's where it gets interesting - the fish can rotate the photophore downward to conceal the light, and can blink it on and off while swimming in zigzag patterns to confuse predators.

Researchers have observed flashlight fish forming synchronized schools where consistent groups of luminous individuals merge into larger coordinated displays. It's similar to how fireflies synchronize their flashing on summer evenings, except it's happening in complete darkness, hundreds of meters underwater. The complexity suggests these aren't random signals but purposeful communication - possibly coordinating hunting strategies or maintaining group cohesion in an environment where visual contact is otherwise impossible.

Lanternfish take photophore sophistication even further. With over 200 species, each possesses a unique pattern of light-producing organs along its body. These patterns are distinct enough that marine biologists can identify individual species just by their arrangement - like a biological barcode written in living light. Lateral photophore patterns serve as species recognition signals, essential for finding mates in the vast oceanic darkness.

"Each of the more than 200 lanternfish species has a unique pattern of light-generating photophores, used in signaling and mating."

- Encyclopedia Britannica

What's particularly fascinating is that these fish can see blue-green bioluminescence from about 100 feet away - remarkable in an environment with no ambient light. A 2025 study on deep-sea shrimp revealed they've evolved enhanced vision specifically for detecting bioluminescent signals, with specialized photoreceptors tuned to the exact wavelengths their prey and predators produce.

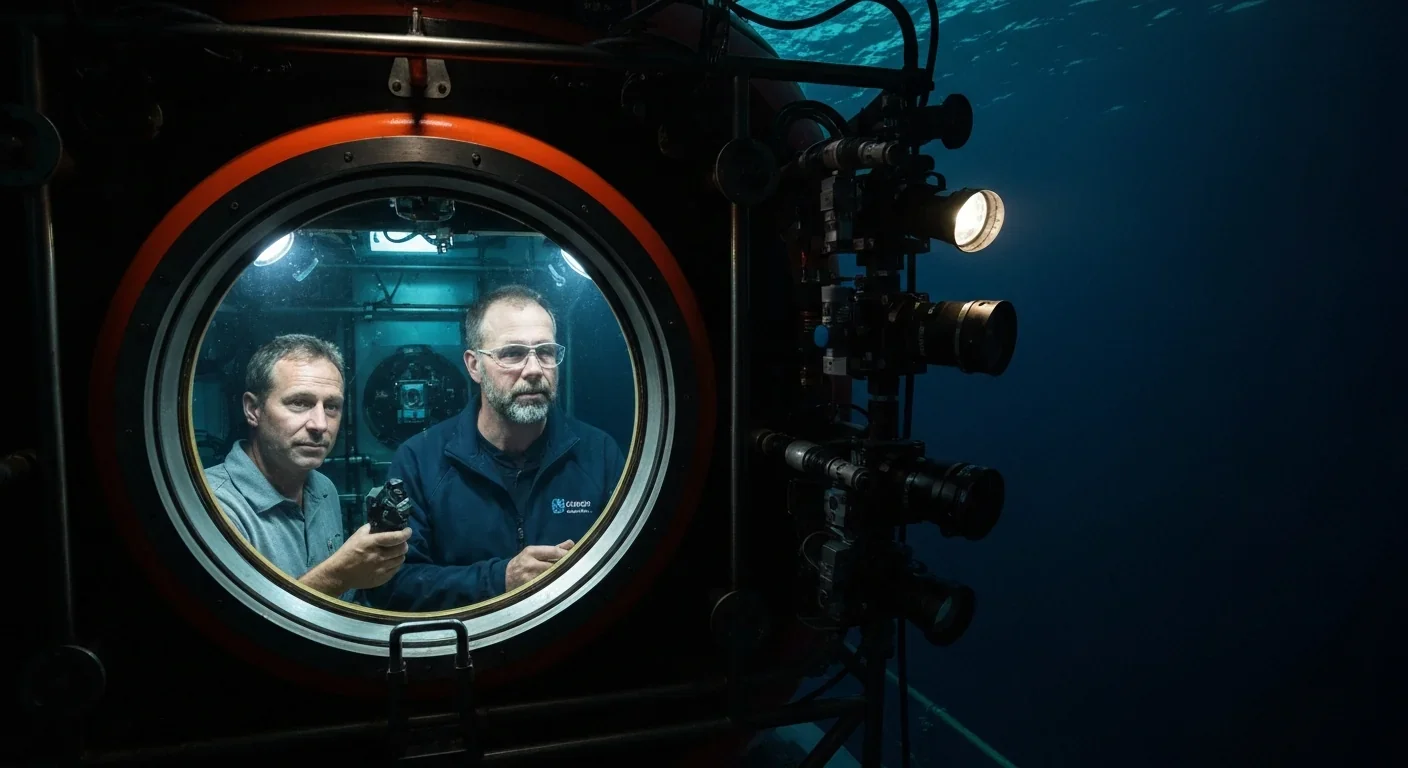

While we've known about bioluminescence for over a century, decoding what these signals actually mean has proven extraordinarily difficult. Bioluminescent creatures often lose their glow when captured, and observing them in their natural habitat requires expensive submersibles equipped with specialized low-light cameras that won't disturb the darkness.

But recent technological advances are changing that. A 2014 study on bioluminescent fish revealed that distinctive flashing patterns might facilitate mating, with males and females of certain species producing different temporal patterns - like a bioluminescent Morse code. Researchers found that species using bioluminescence primarily for communication are diversifying faster than those using it merely for camouflage, suggesting sexual selection is driving rapid evolution of new light-based signals.

The implications are profound. Just as bird species evolve distinct songs, deep-sea fish appear to be evolving distinct flash patterns. This creates reproductive barriers - if your flash doesn't match, you won't get a date - which over time can lead to speciation. The deep sea's darkness isn't limiting diversity; it's enabling it through an arms race of increasingly sophisticated light displays.

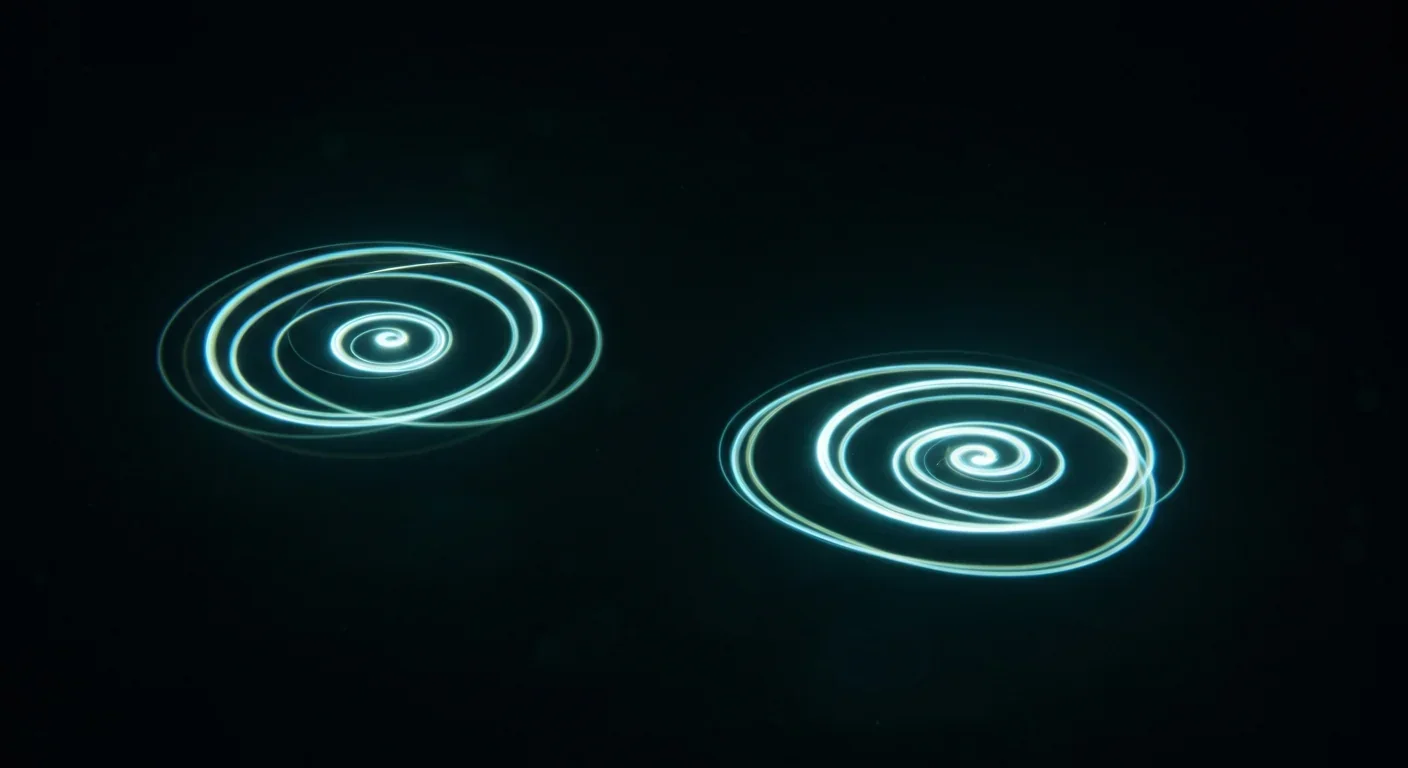

Some of the most elaborate bioluminescent communication happens in tiny crustaceans called ostracods. Male ostracods perform spectacular courtship displays, swimming upward while releasing pulses of bioluminescent chemicals that create luminous trails in the water. Each species has its own signature pattern - some create strings of equally-spaced dots, others produce clustered bursts, still others generate continuous glowing spirals.

A 2015 study on microscopic shrimp found that these bioluminescent sexual displays illuminate evolutionary theory in unexpected ways. Females are extraordinarily selective, choosing mates based on the precise timing, intensity, and pattern of their light shows. This intense sexual selection has driven the evolution of species-specific displays so distinctive that researchers can identify ostracod species from their bioluminescent signatures alone - even without seeing the animal itself.

While courtship might be the most elaborate use of bioluminescence, it's far from the only purpose these signals serve. Deep-sea organisms have weaponized light in remarkably creative ways for defense, predation, and cooperation.

The bobtail squid demonstrates sophisticated light control for camouflage. It houses bioluminescent bacteria in ventral cavities and modulates the cavity openings in response to ambient moonlight penetrating from above. By matching the downwelling light, it eliminates its silhouette, becoming invisible to predators hunting from below - a technique called counter-illumination.

A 2021 study on the Hawaiian bobtail squid revealed even more complexity in this relationship. The bacteria don't just glow passively - the squid actively manages its bacterial population, expelling up to 90% of them each morning and allowing them to regrow during the day. This daily cycle keeps the bacteria population optimal while potentially releasing them into the environment where they might colonize young squid.

The bobtail squid expels 90% of its bioluminescent bacteria each morning, then regrows them during the day - a daily reset that maintains optimal glow.

Other species use bioluminescence as a burglar alarm. When attacked, many deep-sea organisms release clouds of luminescent chemicals or bacteria - essentially throwing up a glowing smokescreen that attracts larger predators to the scene. For a predator, suddenly finding yourself illuminated in the deep sea is like having a spotlight turned on during a heist. The bioluminescent victim is essentially screaming "look over here!" to anything bigger that might find the attacker more appetizing.

The stoplight loosejaw fish - Malacosteus niger - has evolved perhaps the most sophisticated predatory communication system. Most bioluminescence in the ocean is blue or blue-green because water absorbs red wavelengths. But Malacosteus produces red bioluminescence through a specialized photophore beneath its eye, and possesses the rare ability to see red light. It's essentially carrying a pair of night-vision goggles that other creatures can't detect, allowing it to illuminate prey without being seen - the deep-sea equivalent of a stealth predator.

Why did bioluminescence evolve so many times in the deep sea, while remaining relatively rare on land? The answer lies in the unique challenges and opportunities of life in perpetual darkness.

On land, bioluminescence appears primarily in environments where visual communication is difficult - fireflies at dusk, glowworms in caves, certain fungi in dark forests. But in the deep ocean, darkness is constant and universal. Without bioluminescence, visual communication would be impossible. Sound travels well underwater, but slowly - too slowly for precise coordination. Chemical signals disperse unpredictably in three-dimensional currents.

Light, however, travels fast and can be precisely controlled. A 2024 study mapping bioluminescence onto the octocoral phylogeny revealed that this trait first appeared during the Cambrian Explosion around 540 million years ago. Remarkably, most octocorals contain luciferase genes even if they don't currently produce visible light, suggesting a dormant capacity that can be re-activated when evolutionarily advantageous.

This genomic ghost of bioluminescence past indicates that once the biochemical machinery for light production evolved, it was retained even when not actively used - probably because the metabolic cost of maintaining dormant genes is lower than the cost of re-evolving the entire system from scratch.

The evolutionary advantages become clear when you consider the specific challenges of deep-sea life. Finding mates in a three-dimensional space with extremely low population density is extraordinarily difficult. A distinctive bioluminescent signal that can be seen from 100 feet away suddenly makes reproduction feasible. Similarly, hunting becomes more effective when you can lure prey with light or coordinate attacks with hunting partners through synchronized flashes.

Studying bioluminescent communication presents unique methodological challenges. Traditional marine biology often involves collecting specimens for laboratory study, but many bioluminescent organisms lose their glow under stress or die quickly in captivity. The symbiotic bacteria disappear, the chemical substrates are depleted, and the very phenomenon researchers want to study vanishes.

Modern approaches increasingly rely on remote observation. Specialized submersibles equipped with low-light cameras can observe natural behaviors without disturbing them. Some researchers use red light for illumination, which most deep-sea creatures can't see, allowing observation without interference - similar to how wildlife photographers use infrared cameras to film nocturnal animals.

Computer modeling and simulation are also proving valuable. By analyzing the optical properties of bioluminescence, researchers can predict how signals might be perceived at various distances and angles underwater, helping decode which displays might be visible to intended recipients versus unintended eavesdroppers.

Genetic analysis has revealed unexpected patterns. By mapping which species possess which luciferin-luciferase systems, scientists can trace the evolutionary history of bioluminescence and identify convergent evolution - cases where completely unrelated organisms independently evolved similar solutions. This comparative approach has shown that while the chemistry might differ, the communicative functions - mating, predation, defense - remain remarkably consistent across taxa.

"Up to 90% of species living in the deep sea - thousands of meters down where sunlight can't reach - are bioluminescent."

- Marine Biology Research

One particularly innovative approach involves studying preserved specimens in museum collections using techniques that weren't available when they were collected. Modern microscopy can identify photophore structures in century-old specimens, allowing scientists to reconstruct which historical species were bioluminescent even without seeing them glow. Combined with molecular phylogenetics, this creates a timeline of how bioluminescence evolved and diversified over millions of years.

Bioluminescence represents just one solution to the fundamental problem all organisms face: how to exchange information with others of your species. Comparing light-based communication with sound and chemical signals reveals why different environments favor different solutions.

Sound excels at traveling through obstacles and around barriers. Whale songs can travel hundreds of miles through ocean currents. Bird calls penetrate dense forests. But sound travels about four times faster in water than air, which creates problems for precise timing - it's harder to have a "conversation" when there's a delay between speaking and hearing the response.

Chemical communication - pheromones and scent marking - works brilliantly for leaving persistent messages that receivers can detect later. Many fish use chemical signals for territorial marking and identifying relatives. But in the deep ocean, three-dimensional currents disperse chemicals unpredictably. A scent trail that works beautifully for a wolf marking territory on solid ground becomes useless when ocean currents can carry it miles in any direction.

Light-based communication combines the best of both: instantaneous transmission like sound, with the directionality and controllability of visual displays. A lanternfish can flash a signal visible only to potential mates directly ahead while remaining hidden from predators to the side. An anglerfish can illuminate its lure only when prey approaches close enough to strike.

This is why birds use songs (sound travels far in open air), moths use pheromones (chemical signals persist in still evening air), and deep-sea fish use bioluminescence (light provides precision in a dark, three-dimensional environment). Each communication system represents an optimized solution for its specific ecological niche.

Despite recent advances, enormous gaps remain in our understanding of bioluminescent communication. The sheer depth and vast area of the ocean floor means we've likely observed less than 5% of deep-sea bioluminescent behaviors in their natural context.

We don't know the full vocabulary of most species' light signals. Is there a "dialect" difference between populations separated by underwater mountains? Can deep-sea creatures lie with their bioluminescence, producing false signals to deceive predators or rivals? Some terrestrial firefly species practice aggressive mimicry - females imitating the signals of other species to lure and devour males - but we don't know how common deceptive signaling might be in the deep ocean.

The role of individual variation remains mysterious. Do some individual fish have more attractive flash patterns than others, the way some songbirds are more talented singers? Can young fish learn light patterns from adults, or is it entirely genetic? These questions touch on fundamental issues about animal cognition and culture.

Scientists have observed less than 5% of deep-sea bioluminescent behaviors in natural settings - leaving 95% of this light-based language still waiting to be decoded.

Perhaps most intriguingly, we don't understand the sensory experience of bioluminescent communication from the organism's perspective. When a flashlight fish blinks its photophore, is it experiencing something analogous to speech? Is there an aesthetic dimension to bioluminescent displays - do deep-sea creatures find certain light patterns beautiful the way humans might find certain sounds musical?

These aren't just philosophical questions. Understanding the perceptual and cognitive dimensions of bioluminescent communication could reveal whether there are universal principles of aesthetic preference across radically different sensory systems - insights that might inform everything from artificial intelligence design to the search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

As humanity's impact on the oceans intensifies, bioluminescent communication systems face emerging threats. Deep-sea mining operations could disrupt the darkness these signals depend on, introducing artificial lights that interfere with natural signals. Bottom trawling destroys delicate bioluminescent organisms before scientists can even document them.

Climate change presents subtler threats. Many bioluminescent bacteria are temperature-sensitive, and warming waters could disrupt the symbiotic relationships that many deep-sea fish depend on. Changes in ocean chemistry might affect the efficiency of bioluminescent reactions or the availability of essential chemical precursors.

Yet these same organisms might hold solutions to human challenges. The green fluorescent protein (GFP) discovered in the bioluminescent jellyfish Aequorea victoria revolutionized cellular biology, earning its discoverers a Nobel Prize. Researchers are now exploring whether bioluminescent communication systems could inspire new approaches to underwater data transmission, potentially replacing acoustic systems that disturb marine mammals.

Bioluminescent organisms have also become unlikely ambassadors for ocean conservation. When people learn about the intricate light-based conversations happening in the deep ocean - the courting ostracods with their glowing spiral dances, the flashlight fish schools pulsing in synchrony, the anglerfish cultivating its bacterial garden - the deep sea transforms from an abstract dark void into a living, communicating ecosystem worth protecting.

The hidden language of bioluminescence reminds us that intelligence and communication can evolve in forms radically different from our own. While we speak with vibrating air and gesture with reflected sunlight, deep-sea creatures converse through living luminescence, their signals crafted by millions of years of evolution in Earth's most extreme environments.

As our technology advances and our understanding deepens, we're beginning to crack this luminous code. Each discovery - each decoded signal, each identified pattern, each mapped phylogeny - brings us closer to understanding one of evolution's most elegant solutions to the problem of communication. The deep ocean, once thought to be a silent, lifeless void, is revealing itself as a symphony of light, a conversation that has been happening since before humans existed, in a language we're only now learning to read.

And perhaps most remarkably, we've barely scratched the surface. With 90% of deep-sea species potentially bioluminescent and less than 20% of the ocean floor explored, the majority of this light-based language remains unread, waiting in the darkness for someone to illuminate its secrets.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.