Nature's First Farmers: 50 Million Years of Ant Agriculture

TL;DR: Cleaner fish run underwater service stations where predators queue for parasite removal, demonstrating sophisticated cognition, strategic cooperation, and reputation management that rivals human market systems - yet these keystone species face mounting threats from climate change and overfishing.

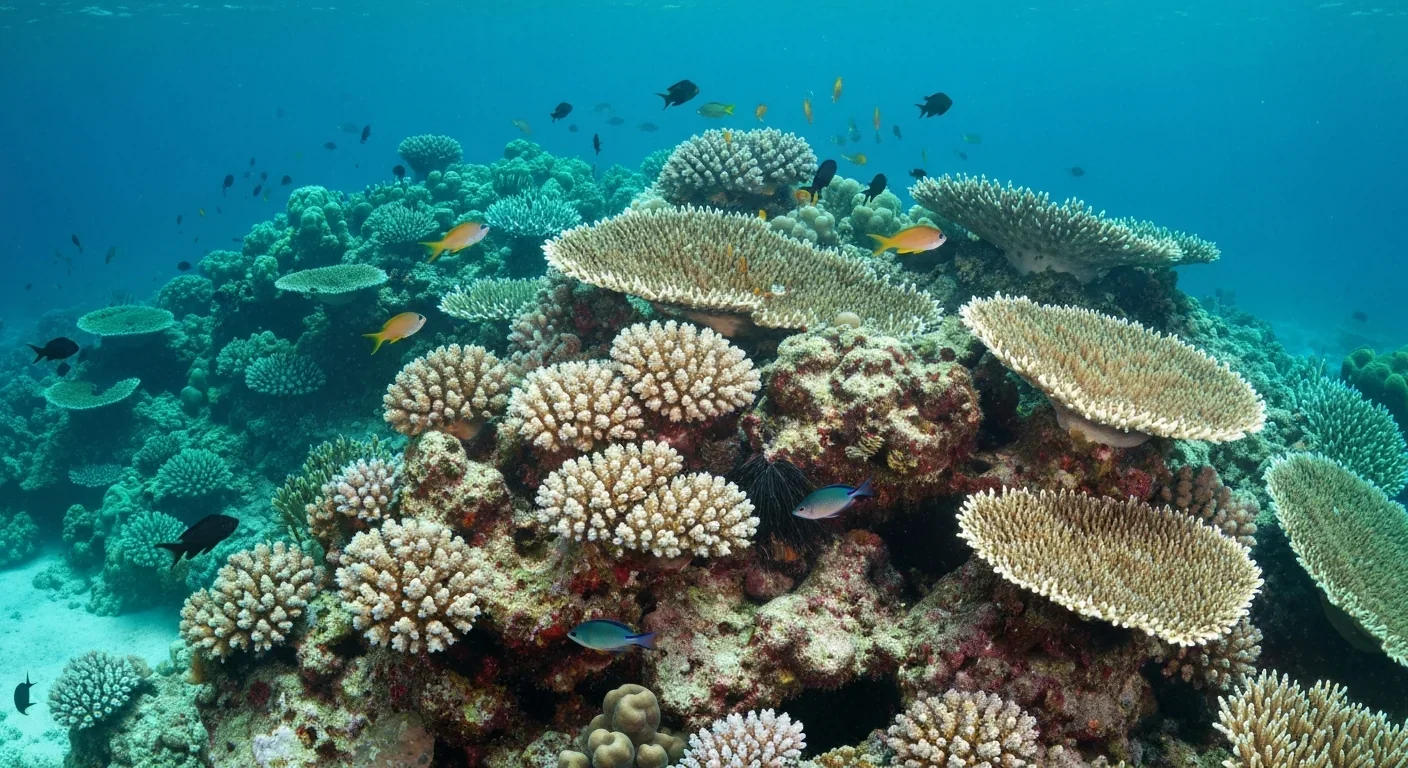

Picture this: a grouper three times your size opens its jaws wide, revealing rows of serrated teeth. Instead of fleeing, you swim directly into its mouth. This happens thousands of times a day on coral reefs worldwide, and it's one of nature's most counterintuitive partnerships.

Cleaner fish - primarily wrasses and gobies no bigger than your finger - establish what marine biologists call cleaning stations: specific reef locations where predatory fish queue up, sometimes for hours, to have parasites, dead skin, and debris removed. The relationship resembles our neighborhood barbershops more than you'd expect. Regulars get preferential treatment. Service quality varies. And yeah, both parties occasionally cheat.

What researchers are discovering challenges everything we thought we knew about fish intelligence, cooperation between natural enemies, and the invisible networks that keep entire ecosystems functioning. Turns out, these tiny janitors aren't just removing parasites - they're running sophisticated businesses that would make economists nod in recognition.

The bluestreak cleaner wrasse (Labroides dimidiatus) is the star of this show, found across coral reefs from the Red Sea to the Western Pacific. Its electric blue stripe acts like a neon "Open for Business" sign, instantly recognizable to hundreds of client species. But wrasses aren't alone. Cleaner gobies - particularly the Caribbean species Elacatinus evelynae - run thriving operations in their own territories, sometimes performing over 110 cleanings per day.

Client fish span the entire reef hierarchy. Manta rays descend from open water. Groupers interrupt hunting routes. Even sharks - species that could swallow a cleaner in one gulp - adopt specific poses and suppress their predatory instincts during cleaning sessions.

The evolutionary puzzle is obvious: why don't predators just eat the help?

The evolutionary paradox: A grouper eating a cleaner wrasse gets a quick meal, yet across millions of years, predators consistently choose the long game - preserving access to parasite removal services that can reduce ectoparasite loads by up to 80%.

Natural selection typically favors immediate gains. A grouper eating a cleaner wrasse gets a quick meal. Yet across millions of years and thousands of species, predators consistently choose the long game: preserving access to parasite removal services that can reduce ectoparasite loads by up to 80%.

The answer lies in what evolutionary biologists call reciprocal altruism - you scratch my back, I'll scratch yours, and we'll both do better than if we fought. But here's where it gets interesting. This isn't just instinct. Recent research shows cleaner fish actively manipulate the relationship through strategic behavior that looks remarkably like calculated business decisions.

Studies from 2002 revealed that cleaner wrasses adjust their service quality based on who's watching. When a long queue of potential clients is visible, cleaners cheat less - they're managing their reputation. When only one client is present and no observers lurk nearby, cleaners are more likely to take a bite of nutritious client mucus instead of just removing parasites.

Client fish aren't passive consumers either. They remember individual cleaners and avoid those who cheated them previously. Some clients even spread the word - if a cleaner develops a bad reputation, entire groups of fish will bypass that station, sometimes for weeks.

Before any cleaning begins, an intricate dance of signals establishes mutual intent. Client fish adopt species-specific poses: some perform head-stands, others spread their fins wide or change color. A few species even open their mouths and gill covers - a gesture that in any other context would signal aggression.

Cleaner wrasses respond with their own choreography, performing a distinctive motion where they wiggle their rear end up and down. Marine biologist Redouan Bshary, who has spent decades studying these interactions, describes it as a negotiation ritual. The cleaner essentially asks, "Ready for service?" The client's stillness answers, "Proceed."

What happens next demonstrates sophistication that would be impressive in mammals. Cleaners prioritize clients strategically. Transient predators - fish just passing through - get served before resident herbivores. Why? Because the predator has options; it can visit another cleaning station down the reef. Regular clients, however, have already invested in this location and are more likely to tolerate a short wait.

"The system relies on recognition through a neurochemical cocktail of hormones including arginine vasotocin, isotocin, and serotonin that enables behavioral flexibility - the biological equivalent of reading the room."

- Marine Biology Research

The system relies on recognition. Hormones including arginine vasotocin, isotocin, and serotonin influence how cleaners remember clients, adjust interaction durations, and decide whether to cooperate or cheat. It's a neurochemical cocktail that enables behavioral flexibility - the biological equivalent of reading the room.

In the Caribbean, cleaner gobies face a problem: during certain seasons, parasites become scarce. Rather than go hungry, Elacatinus evelynae supplements its diet by eating client mucus and scales - behavior researchers classify as "cheating" because it benefits the cleaner at the client's expense.

Clients cheat too, though more subtly. Some fish have learned to mimic the poses of more valuable clients, essentially cutting in line by pretending to be transient predators when they're actually local residents with nowhere else to go.

Juvenile cleaner wrasses cheat significantly more than adults, biting clients far more frequently. As they mature, their behavior shifts toward honest service - suggesting they learn that long-term cooperation pays better than short-term exploitation.

When cleaners work in male-female pairs, social dynamics add another layer. If the smaller female bites a client, the larger male sometimes chases her away from the cleaning station - punishment behavior that appears designed to protect their shared reputation. Economists studying these interactions see striking parallels to human market regulation: the male acts as quality control, enforcing standards to maintain customer trust.

For decades, scientists assumed fish operated primarily on instinct. Then in 2019, bluestreak cleaner wrasses passed the mirror self-recognition test - previously achieved only by great apes, elephants, dolphins, and magpies.

Researchers placed a mark on the wrasse's body where the fish could only see it in a mirror. The cleaner examined the mark, then tried to scrape it off by rubbing against the tank bottom. This suggests some form of self-awareness, though scientists continue debating what exactly the fish understands about its reflection.

What's not debatable is the sophistication of their decision-making. Brain-to-body ratio studies indicate cleaner wrasses possess cognitive abilities comparable to some primates in specific tasks - particularly social memory and strategic cooperation.

Cleaner wrasses demonstrate tactical deception, providing gentle fin massages to client fish when potential future clients are watching, then reverting to rougher cleaning when unobserved - strategic thinking that rivals many mammals.

They demonstrate tactical deception, providing gentle fin massages to client fish when potential future clients are watching, then reverting to rougher (faster) cleaning when unobserved. They assess risk versus reward, choosing when to cheat based on social context. They even appear to experience something like stress when separated from familiar clients.

These aren't the mindless automatons we once imagined. They're strategic thinkers playing a complex social game.

Remove cleaner fish from a reef section, and the entire community structure begins to collapse within weeks. Ectoparasite loads on client fish spike. Disease spreads. Fish stress levels increase, measurable through elevated cortisol. Some species abandon the area entirely, seeking reefs with functioning cleaning stations.

One landmark study removed all cleaner wrasses from experimental reef patches. Within months, client fish diversity dropped by nearly 50%. It wasn't just about parasites - cleaning stations serve as keystone sites that influence biodiversity through mechanisms we're only beginning to understand.

Cleaning interactions may facilitate social tolerance among species that would otherwise avoid each other. Predators visiting stations enter a kind of truce, creating temporary safe zones where smaller fish can forage nearby. The stations effectively function as neutral territories, expanding usable habitat for species that would normally hide when predators are present.

The economic value is measurable. In regions where cleaner fish populations thrive, reef health indicators consistently score higher. Fish grow larger, reproduce more successfully, and display lower mortality from parasitic infections. For communities dependent on reef fisheries or dive tourism, the presence of healthy cleaning stations translates directly into economic benefits.

Mathematicians studying cleaner fish interactions see a living laboratory for game theory principles usually applied to economics or political science.

The relationship fits what's called an iterated prisoner's dilemma. Both parties benefit from cooperation, but each faces temptation to cheat for immediate gain. The optimal strategy - cooperate but retaliate against cheaters - is exactly what we observe in cleaner-client interactions.

Models predict that cooperation should collapse when interactions become anonymous or one-time-only, since neither party expects future encounters. Reef systems confirm this: cleaners cheat more often with first-time clients than with regulars. The mathematical prediction matches biological reality.

"Cleaners use what we call 'image scoring' - they monitor whether they're being observed and adjust behavior accordingly, similar to how humans act more generously when watched."

- Dr. Redouan Bshary, Behavioral Ecologist

Researchers have even identified what economists call "punishment mechanisms" and "reputation markets." Clients punish cheating cleaners by swimming away mid-session or avoiding them in the future. Cleaners maintain reputations through consistent service, attracting more clients and thriving in premium reef locations.

Redouan Bshary's work revealed that cleaners use what he calls "image scoring" - they monitor whether they're being observed and adjust behavior accordingly, similar to how humans act more generously when watched. It's indirect reciprocity: I help you while others watch, enhancing my reputation so future partners will choose me.

Climate change, overfishing, and reef degradation threaten cleaner fish populations worldwide. As reefs bleach and structural complexity declines, cleaning stations disappear. The services they provided - parasite control, stress reduction, social facilitation - vanish with them.

There's a cascading effect. Fish populations that relied on cleaning services experience higher parasite loads, compromising immune function just as warming waters introduce new diseases. Stressed fish reproduce less successfully. Predators that previously visited cleaning stations must expand their ranges, altering community dynamics.

Some aquarium trade practices specifically target cleaner wrasses because they're popular among hobbyists who want natural parasite control. While sustainable collection exists, overexploitation of certain populations has reduced cleaner density on heavily harvested reefs, with ripple effects through the entire ecosystem.

The good news: cleaner fish respond well to protection. Marine protected areas that prohibit collection see rapid recovery of cleaning stations, with corresponding improvements in client fish health and diversity.

Cleaner fish mutualism is rewriting our understanding of what small brains can accomplish. These fish demonstrate:

Long-term memory for individual partners across hundreds of interactions, strategic decision-making based on social context, tactical deception and impression management, punishment and reconciliation behaviors, and possible self-recognition and theory of mind.

None of this requires a large cortex or years of development. A wrasse with a brain the size of a grain of rice navigates social complexity that would challenge many mammals.

Dr. Alex Jordan, a behavioral ecologist studying cleaner fish cognition, points out that we've consistently underestimated fish intelligence because we designed tests based on what works for primates. When we study fish doing fish things - navigating three-dimensional reef structures, managing dozens of social relationships, balancing cooperation and competition - we see cognitive abilities we never suspected.

The implications extend beyond marine biology. If sophisticated cooperation evolved independently in fish, insects, and mammals, it suggests that the building blocks of social intelligence are more fundamental than we thought. Convergent evolution points to universal principles underlying cooperation across wildly different brain architectures.

Strip away the scientific terminology, and cleaning stations operate remarkably like human service businesses. There's competition for prime real estate - reef locations with high client traffic. There's brand management through reputation. There's variable pricing: clients that offer better meals (more parasites) sometimes get priority service.

Cleaners even engage in what marketers call "customer retention strategies." The tactile massage they provide - running their fins along a client's body - doesn't remove parasites. But it does reduce client aggression and increase session duration, much like a scalp massage at the hair salon keeps customers relaxed and returning.

Market failures occur too. When cleaner populations crash, client fish can't simply find alternatives - there aren't enough cleaning stations to meet demand. The service gap creates a bottleneck that limits how many fish a reef can support, similar to how lack of infrastructure limits economic development.

Economists note that cleaning stations solved the same problems human markets face: establishing trust between strangers, preventing cheating, enforcing quality standards, and maintaining cooperation despite incentives to defect.

Economists studying these systems note that cleaning stations solved many of the same problems human markets face: how to establish trust between strangers, prevent cheating, enforce quality standards, and maintain cooperation despite incentives to defect. The solutions - reputation systems, repeat interactions, third-party monitoring, punishment mechanisms - look strikingly similar to institutions we've built.

Scientists are now exploring whether cleaners experience anything like empathy or emotional contagion. Do they register client stress? Some evidence suggests cleaners become more attentive with distressed clients, but whether this reflects emotional response or strategic adjustment to behavioral cues remains unclear.

We're also asking how climate change might disrupt not just cleaner populations, but the behavioral plasticity that makes the mutualism work. As ocean chemistry shifts and temperatures rise, will the neurochemical systems regulating cleaner behavior remain stable? Early studies hint that acidification might impair fish cognition, potentially destabilizing these carefully evolved partnerships.

Another frontier: applying insights from cleaner fish systems to understand human cooperation. Game theorists and behavioral economists are mining decades of cleaner fish data to test theories about reputation, trust, and the evolution of fairness. If cleaner wrasses follow the same mathematical principles that govern human markets, it suggests deep evolutionary roots for behaviors we consider uniquely human.

Next time you hear someone dismiss fish as simple creatures operating on pure instinct, remember the cleaner wrasse. Remember the queue management, the reputation tracking, the strategic decision-making, the punishment of cheaters, the cultivation of long-term partnerships.

These fish aren't just removing parasites. They're maintaining social networks that structure entire ecosystems. They're demonstrating cognitive sophistication that challenges our definitions of intelligence. They're running service businesses that parallel our own economic systems in uncanny ways.

Most importantly, they're irreplaceable. Every cleaning station that disappears represents not just lost species, but collapsed networks, broken partnerships, and dissolved trust that took millennia to evolve.

We're only beginning to understand what they are, what they do, and what we lose when they're gone. The underwater barbershops are open for business. The question is whether we'll protect them long enough to learn everything they have to teach us.

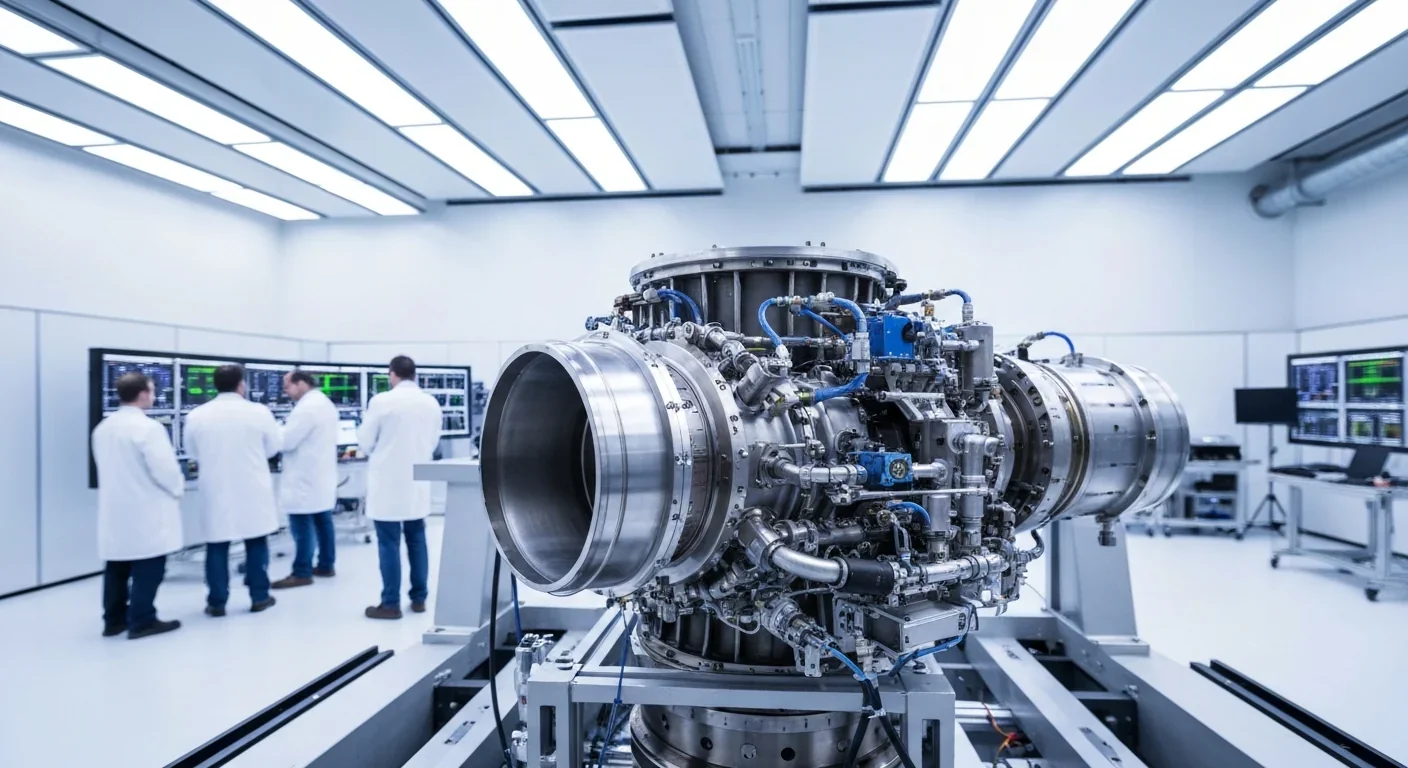

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

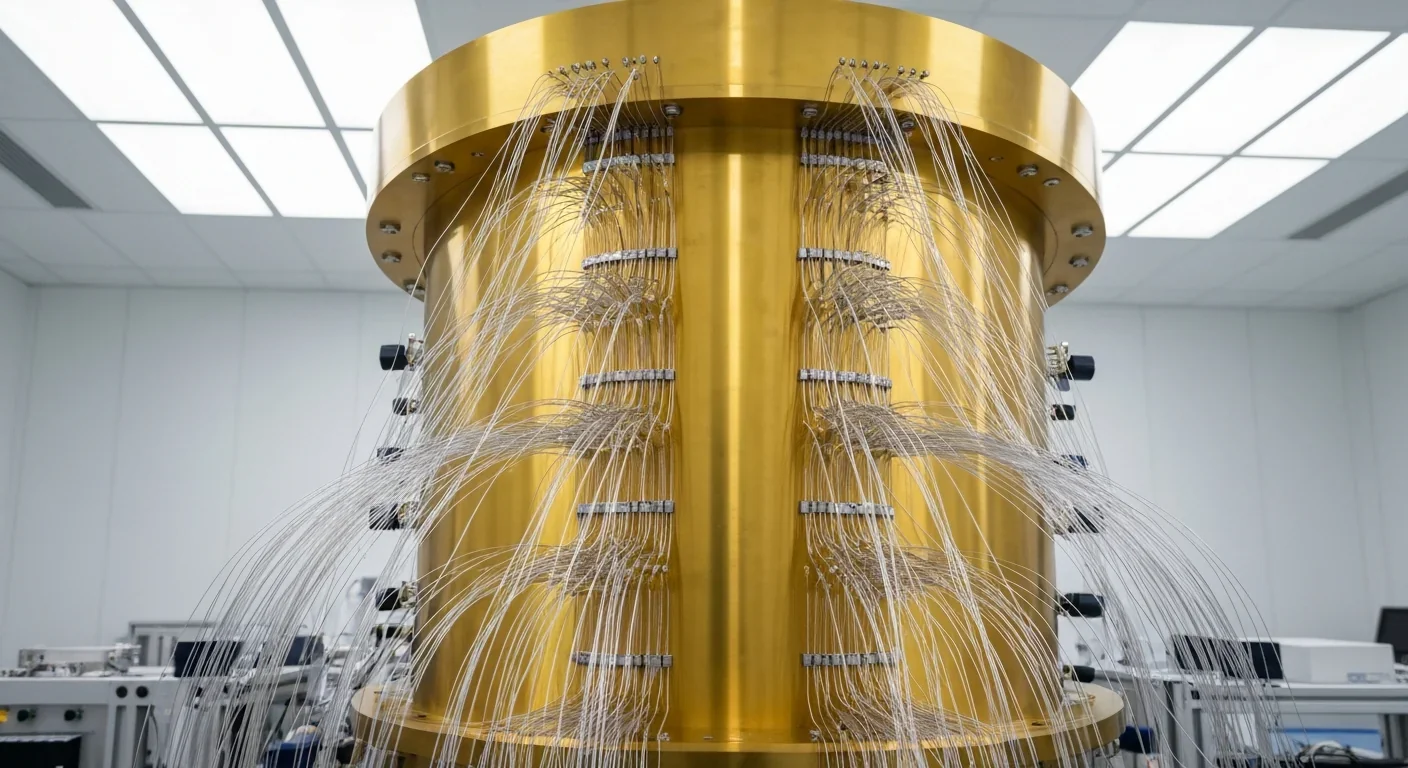

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.