Nature's First Farmers: 50 Million Years of Ant Agriculture

TL;DR: Bamboo species worldwide synchronize their flowering after decades of waiting, using genetic clocks that maintain precision across continents. These mass flowering events trigger ecological cascades affecting everything from rodent populations to panda survival.

In a world where Japanese bamboo forests began flowering in 2020 after precisely 120 years of silence, scientists are witnessing one of nature's most extraordinary biological clocks in action. Across continents, from the mountains of Japan to the forests of India, bamboo species are demonstrating a phenomenon that challenges our understanding of plant communication and timing. These events aren't random occurrences but precisely orchestrated reproductive spectacles that unfold with clockwork regularity after decades, sometimes more than a century, of vegetative growth.

The scale and synchronization of these flowering events defy conventional botanical wisdom. When Phyllostachys bambusoides flowers every 120 years, every member of that species worldwide blooms simultaneously, regardless of local climate conditions or geographic separation. This coordination spans continents and ecosystems, suggesting an internal timing mechanism so robust that it maintains accuracy across generations of human observers. The phenomenon has captured scientific attention not just for its rarity, but for its profound ecological and economic consequences that ripple through entire ecosystems and human communities.

Scientists describe bamboo's synchronized flowering as nature's equivalent of an internal alarm clock, one that ticks for decades before finally ringing. According to biological research on bamboo lifecycles, this synchronization is "a natural, genetically programmed event" that operates independently of environmental triggers. Unlike most plants that respond to seasonal cues like temperature or daylight, bamboo species maintain their flowering schedule through what appears to be a genetically encoded countdown timer embedded in their cellular machinery.

Bamboo plants can count decades with greater accuracy than many human-designed systems, maintaining their flowering schedule even when transplanted across continents.

The precision of this biological clock is remarkable. Melocanna baccifera has flowered almost fully synchronically every 48 years, with verified bloomings documented in 1863, 1911, 1959, and 2007. The next event is anticipated for 2055, a prediction scientists make with unusual confidence. This regularity suggests that bamboo plants possess a molecular mechanism capable of counting years with greater accuracy than many human-designed systems. Recent DNA studies have identified flowering control genes in bamboo, though the exact molecular pathways that enable such long-term timekeeping remain partially mysterious.

What makes this phenomenon even more intriguing is how transplanted bamboo maintains its schedule. When bamboo from Asia is moved to South America or Africa, it continues to flower in sync with its parent population thousands of miles away. This suggests the timing mechanism is so deeply embedded in the plant's genetics that neither geographic displacement nor environmental change can reset the clock. The bamboo remembers its ancestral rhythm, carrying this temporal memory across oceans and continents.

The past few years have provided unprecedented opportunities to study mass bamboo flowering in real-time. The 2020 mass flowering event of Phyllostachys nigra var. henonis in Japan marked the first time this species had bloomed since 1900, offering scientists a once-in-a-lifetime research opportunity. Remarkably, approximately 80% of the studied plants entered the reproductive phase simultaneously, though paradoxically, none produced viable seeds. This mass flowering without successful reproduction raises questions about the evolutionary strategy behind such resource-intensive events.

In Northeast India, the phenomenon takes on a different character with distinct cycles that local communities have tracked for generations. The region experiences two major bamboo flowering events: Mautam, occurring every 48 years with Melocanna baccifera, and Thingtam, happening at different intervals with other species. The most recent Mautam event in 2007-2008 affected thousands of square kilometers, while a Thingtam event in 2024 impacted 122 villages across Mizoram state. Satellite monitoring has documented these mass flowering events covering vast geographic areas, with some events visible from space as entire forest canopies transform from green to brown.

"During this period, bamboo dedicates a tremendous amount of stored energy from its root system to produce flowers and seeds. For many monocarpic bamboo species, this massive energy expenditure is followed by the death of the entire plant or colony."

- Biology Insights research on bamboo lifecycles

Scientists have now documented similar synchronized flowering events beyond India in countries including Laos, Japan, Madagascar, and South America, confirming that this phenomenon is truly global in scope. Each event follows the same pattern: sudden flowering after decades of vegetative growth, followed by seed production and then complete die-off of the parent plants. The synchronization holds even for bamboo populations that have been separated for centuries, suggesting an evolutionary strategy refined over millions of years.

When bamboo forests flower and die en masse, the ecological consequences cascade through entire ecosystems like falling dominoes. The immediate effect is a massive pulse of resources, with Melocanna baccifera producing up to 80 tonnes of fruit per hectare during flowering events. This sudden abundance of high-sugar fruit triggers what scientists call a "resource pulse" that fundamentally restructures local food webs. The sugar-rich bamboo fruit, rather than being high in protein as previously thought, acts as a powerful attractant for wildlife, particularly rodents.

The relationship between bamboo flowering and rodent populations has been documented for centuries, with local communities coining the term "rat floods" to describe the phenomenon. During the 2024 Thingtam event in Mizoram, rodent populations exploded following bamboo fruiting, leading to the destruction of paddy fields belonging to 3,983 families. The mechanism is straightforward yet devastating: bamboo fruits provide unlimited food for rodents, causing rapid population growth. Once the bamboo seeds are exhausted, these enlarged rodent populations turn to agricultural crops, creating famine conditions that can persist for years.

A single mass bamboo flowering event can produce up to 80 tonnes of fruit per hectare, triggering ecological cascades that affect entire regions for years.

For iconic species like the giant panda, bamboo flowering events represent existential threats. Following the 1975-1983 mass flowering episode in China, the panda population declined from approximately 2,000 to less than 1,000 individuals over the following decade. Pandas refuse to eat flowering bamboo, and with entire forests dying simultaneously, they face starvation unless they can migrate to non-flowering bamboo areas. Modern conservation efforts now include habitat corridors and translocation programs specifically designed to counter flowering-induced food shortages.

The transformation extends beyond individual species to entire forest structures. Mass bamboo die-offs can convert dense forests into open meadows within months, increasing flood risk and erosion while eliminating habitat for countless species. The ecological succession that follows takes decades, with pioneer species gradually recolonizing areas until new bamboo seedlings eventually reclaim their ancestral territory.

The economic reverberations of mass bamboo flowering extend far beyond agricultural losses, touching every aspect of life in bamboo-dependent communities. In regions where bamboo provides rapid returns on investment within 3-5 years of planting, mass die-offs eliminate both current income and future economic potential for decades. The construction industry, which relies on bamboo as a sustainable building material, faces sudden supply crises that can persist for years as new growth slowly matures.

The 2024 Thingtam event in Northeast India illustrates the cascading economic effects. Over 4,700 farming families across Mizoram experienced crop destruction from rodent infestations triggered by bamboo flowering. Traditional responses include deploying indigenous trapping methods with evocative names like vaithang, mangkhawng, and thangchep, representing centuries of accumulated wisdom about managing these cyclical disasters. Communities have developed governance structures and resource management strategies that span multiple Mautam cycles, passing knowledge through generations about surviving these predictable yet devastating events.

Cultural narratives surrounding bamboo flowering reflect its profound impact on human societies. In many Asian cultures, bamboo flowering is viewed as an omen, sometimes of prosperity from the brief abundance, but more often of coming hardship. The regularity of these events has been incorporated into traditional agricultural calendars, with some communities planning major life events around anticipated flowering cycles. Modern governments have begun incorporating satellite-based monitoring systems to predict flowering events, allowing for proactive famine prevention and economic mitigation strategies.

The evolutionary logic behind waiting 30 to 120 years to reproduce seems counterintuitive in a world where most plants flower annually. Yet scientists propose this strategy, known as mast seeding or predator satiation, represents a sophisticated evolutionary solution to seed predation. By flowering so rarely, bamboo species prevent the buildup of specialized seed predators that could devastate their reproductive efforts. When flowering finally occurs, the sheer volume of seeds produced overwhelms potential predators, ensuring some seeds survive to establish the next generation.

"This synchronized flowering is a natural, genetically programmed event, often described as an internal 'alarm clock' within the plant's cells."

- Biology Insights on bamboo's genetic timing mechanism

The synchronization aspect adds another layer of evolutionary brilliance. If individual bamboo plants flowered at different times, seed predators could move from one flowering patch to another, potentially consuming all seeds. But when entire species flower simultaneously across vast geographic areas, even exponentially growing predator populations cannot consume all the seeds. Research indicates this synchronized flowering maximizes seed dispersal efficacy while minimizing losses to predation.

The energy investment required for this strategy is enormous. Bamboo plants spend decades accumulating resources in their extensive rhizome systems, building up reserves for one massive reproductive effort. During flowering, bamboo dedicates tremendous stored energy from its root system to produce flowers and seeds, an expenditure so great that it invariably leads to the death of the parent plant. This "big bang" reproduction strategy trades longevity for a single, spectacular reproductive event designed to overwhelm natural constraints on seedling establishment.

As global temperatures rise and weather patterns shift, scientists are investigating whether climate change might disrupt these ancient flowering cycles. Current research suggests that while bamboo's genetic clock continues ticking, environmental stresses could affect flowering success and seed viability. The 2020 Japanese flowering event, where 80% of plants flowered but produced no viable seeds, raises concerns about whether changing conditions are interfering with successful reproduction.

Temperature fluctuations and altered rainfall patterns could affect not just flowering timing but also the survival of bamboo seedlings after mass flowering events. Climate models suggest that traditional bamboo ranges may shift, potentially breaking the synchronization between populations that have flowered together for millennia. If different populations begin flowering at different times due to local climate variations, the evolutionary advantage of synchronized mass flowering could be lost.

The implications extend beyond bamboo itself to all species dependent on these ecosystems. Conservation strategies now incorporate climate change projections into habitat management plans, recognizing that future flowering events may not follow historical patterns. Scientists are developing new monitoring techniques, including the Bamboo Index Model that combines vegetation indices with stress indicators to predict and track flowering events in a changing climate.

The phenomenon of synchronized bamboo flowering represents one of nature's most remarkable demonstrations of biological timekeeping, ecological interconnection, and evolutionary strategy. As we face an uncertain climatic future, these ancient cycles offer both warnings and wisdom about the deep temporal rhythms that govern life on Earth. The next major flowering events, including the anticipated 2055 Mautam in Northeast India, will provide crucial data about whether these biological clocks can maintain their precision in an rapidly changing world.

The next predicted Melocanna baccifera flowering in 2055 will test whether these ancient biological clocks can maintain their precision in our rapidly changing climate.

For communities living with bamboo, traditional knowledge combined with modern technology offers hope for managing future flowering events. Remote sensing capabilities now enable governments to provide early warning systems, while ecological research continues revealing the complex web of interactions triggered by mass flowering. Understanding these patterns isn't just academic curiosity, it's essential for protecting endangered species, ensuring food security, and maintaining the economic stability of millions who depend on bamboo resources.

The story of bamboo's patient wait and spectacular flowering reminds us that nature operates on timescales far beyond human experience. These plants, counting decades with cellular precision, synchronizing across continents through genetic memory, and reshaping entire ecosystems with their death and rebirth, challenge us to think beyond our abbreviated temporal horizons. In studying bamboo's remarkable flowering cycles, we glimpse the deep time of evolution and the intricate choreography of life that unfolds across generations. As one researcher noted, we're not just observing plants flowering, we're witnessing an ancient biological symphony that has been playing long before humans learned to listen, and will likely continue long after we're gone.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

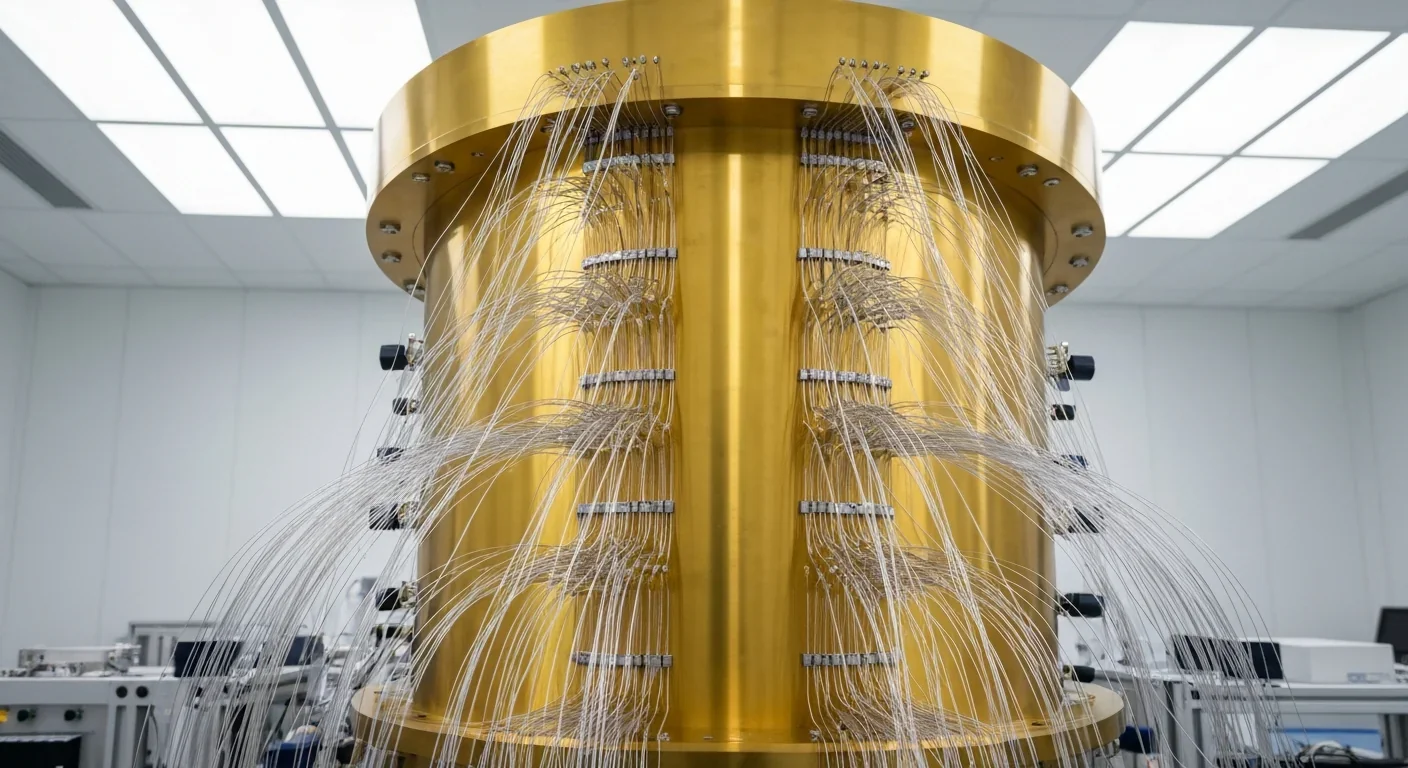

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.