Nature's First Farmers: 50 Million Years of Ant Agriculture

TL;DR: Animal groups coordinate complex movements without leaders through simple neighbor-following rules. Recent discoveries about starlings, locusts, fish, and ants reveal that collective intelligence emerges from local interactions, inspiring new robotics and AI systems.

A million starlings wheel across the Danish sky in patterns so synchronized they look choreographed. Locusts the size of your thumb coordinate into swarms that darken horizons across entire continents. Schools of sardines twist through ocean currents like liquid silver, turning as one to evade predators. These spectacles share something profound: no individual is in charge. There's no conductor, no general, no CEO calling the shots. Just thousands or millions of creatures following simple rules, creating intelligence that emerges from the crowd itself.

For decades, scientists assumed these animal collectives followed basic physics, like magnetic particles aligning in a field. Turns out, the reality is far stranger and more sophisticated than anyone imagined.

In 2008, researchers from Rome's Centre for Statistical Mechanics did something no one had attempted before: they filmed 4,000 starlings in three dimensions as they performed their sunset murmurations. The high-speed cameras captured every bird's position with millimeter precision, revealing a pattern that defied expectations.

Each starling wasn't tracking every bird nearby. It wasn't even maintaining a fixed distance from its neighbors. Instead, each bird synchronized with exactly six to seven of its closest companions, regardless of how near or far they actually were. A starling surrounded by hundreds might track the same number of neighbors as one in a group of twenty.

This discovery overturned decades of modeling. Scientists had assumed animals used what's called a "metric rule" - maintaining a specific distance from others, like cars on a highway keeping two car-lengths apart. But nature chose something cleverer: a topological rule. The birds rank their neighbors by proximity and focus on a fixed number, creating overlapping communication networks that ripple information across thousands of individuals in milliseconds.

Why seven? That number keeps appearing across species. It might reflect a cognitive sweet spot - enough connections to stay coordinated, few enough to process in real time.

Birds react to their neighbors in 20 to 40 milliseconds, faster than you can blink. Managing seven relationships at that speed appears to be what evolution settled on as optimal.

Stand beneath a starling murmuration and you'll witness one of nature's most hypnotic displays. Tens of thousands of birds twist and pulse through the air like smoke in wind, forming shapes that shift faster than conscious thought. The flock compresses into tight balls when a peregrine falcon dives, then explodes outward in waves that look almost like detonations.

Here's what makes it remarkable: murmurations have no leader and follow no plan. No bird decides where the group should go. Instead, each individual applies three simple rules that Craig Reynolds formalized back in 1987 in his famous "Boids" model: avoid colliding with neighbors too close, move in the same direction as nearby birds, and stay near the group.

From those basic instructions, complexity blooms. High-speed footage shows starlings maintain tighter spacing with neighbors to their sides than those in front or behind. This lateral clustering creates a coordinated visual field where information transfers almost instantaneously. When one bird shifts direction, that movement cascades through overlapping networks of seven-bird clusters, propagating across the entire murmuration with almost no degradation.

"The physics here resembles what scientists call a critical system - a state where the whole group hovers on the edge between order and chaos."

- Research on Starling Murmuration Dynamics

The physics here resembles what scientists call a "critical system" - a state where the whole group hovers on the edge between order and chaos. In this state, small changes can ripple through the entire population incredibly fast, but the system remains stable enough to avoid falling apart. It's the same principle that allows starling roosts to pack more than 500 birds per cubic meter without constant collisions.

Timing matters too. Murmurations typically form about an hour before sunset and can last up to 45 minutes before the flock drops into trees or reeds to roost. This temporal coordination suggests these gatherings serve multiple functions: predator avoidance, certainly, but also information exchange. Larger roosts allow birds to share knowledge about food patches discovered during the day, turning the murmuration into a living database of foraging intelligence.

Just when researchers thought they understood collective motion, locusts upended everything.

The 2020 East African locust outbreak was catastrophic - swarms destroyed roughly 160 million kilograms of crops, causing $8.5 billion in losses. As scientists rushed to understand how these insects coordinate movements across such massive scales, they discovered something unexpected: locusts don't follow the rules everyone assumed governed collective behavior.

Traditional models, including the three-zone Boids framework, assume animals explicitly align their direction of movement with neighbors. Seems logical - if everyone faces the same way, the group moves together. But when researchers subjected locusts to virtual reality experiments, placing them between holographic swarms on panoramic screens, the insects revealed a different strategy entirely.

Locusts don't align with their neighbors' direction. Not explicitly, anyway. Instead, their brains maintain what's called a "ring attractor network" - a neural structure that represents the bearing to each neighbor. These bearings compete within the locust's brain through internal consensus dynamics, and the winning direction becomes the insect's heading. It's less like following arrows and more like processing conflicting GPS signals until one route emerges as consensus.

Even more fascinating: the same neurons that drive swarming behavior in gregarious locusts produce the exact opposite response in solitary individuals. When population density is low, these circuits tell the locust to avoid others. When chemical signals (particularly serotonin) indicate crowding, the circuits flip, and the same neurons now drive attraction. It's like a light switch wired to control both on and off depending on context.

This cognitive framework explains why visual information quality matters more than quantity. A locust doesn't need to see hundreds of neighbors - it needs coherent visual cues from a few.

This cognitive framework explains why visual information quality matters more than quantity. A locust doesn't need to see hundreds of neighbors - it needs coherent visual cues from a few, which its ring attractor network can integrate into a clear directional consensus. Density barely factors in. Clarity does.

"It's really about the quality of information, not the quantity," explained researcher Sercan Sayin. That principle might extend far beyond locusts. Fish schools, bird flocks, even mammal herds may rely more on processing coherent signals than simply counting neighbors.

Underwater, the rules shift but the principles endure. Fish schools face challenges birds never encounter: three-dimensional navigation in a medium 800 times denser than air, with visibility that can drop to meters instead of miles. Yet they achieve coordination that rivals any murmuration.

Fish have an advantage birds lack: the lateral line system, a sensory organ running along each side of their body that detects hydrodynamic pressure. When a neighboring fish beats its tail, it creates vortices in the water. Those pressure waves hit the lateral line, giving each fish a continuous feed of exactly where its neighbors are and how fast they're moving, even in murky water or darkness.

Vision still dominates in clear conditions, but the lateral line provides redundancy. Together, these senses let schools maintain incredibly tight formations. Some species school so precisely they reduce hydrodynamic drag, essentially drafting off each other's tail-beats like cyclists in a peloton. The energy savings can reach 30% on long migrations - the equivalent of getting an extra third of your journey for free.

Schools also demonstrate sophisticated collective decision-making. Research on small fish groups showed they use a quorum rule: individuals watch the decisions of others before committing to their own choice. This creates a cascading consensus where accuracy improves as group size increases. Instead of everyone making independent (and potentially wrong) calls, the fish essentially poll each other, and the majority view tends to be more accurate than any single individual's judgment.

The defensive benefits are equally impressive. When a predator attacks a school, it faces what researchers call the "confusion effect" - hundreds of similar targets moving in coordinated but unpredictable patterns make singling out one fish neurologically difficult. Combine that with the dilution effect (the more fish, the lower your individual odds of being the one caught), and schooling becomes a survival strategy that evolution has refined across thousands of species.

During sardine runs off South Africa, schools can number in the billions, creating bait balls visible from space. These aggregations attract predators from all directions - sharks from below, dolphins from the sides, seabirds diving from above - yet most sardines survive through sheer coordinated chaos.

Not all collective intelligence relies on vision or hydrodynamics. Ants built their decentralized networks on chemistry.

When a scout ant discovers food, it heads back to the colony while laying down a pheromone trail. Other ants encounter this chemical path and follow it to the food source. If the source is high quality, those ants also lay pheromone on their return trip, reinforcing the trail. More pheromone attracts more ants, which deposit more pheromone, creating a positive feedback loop.

Here's where it gets clever: pheromone evaporates. Shorter paths to food get reinforced more frequently because ants complete the round trip faster, depositing fresh pheromone before the trail fades. Longer paths receive fewer reinforcements and gradually disappear. The colony doesn't calculate distances or compare routes - it simply follows chemical gradients, and the optimal path emerges from thousands of individual decisions.

"This process, called ant colony optimization, has been translated directly into algorithms that solve complex routing and scheduling problems in telecommunications networks and logistics."

- Applications of Collective Animal Behavior

This process, called ant colony optimization, has been translated directly into algorithms that solve complex routing and scheduling problems in telecommunications networks and logistics. Engineers realized that ants had already solved the traveling salesman problem millions of years before humans invented computers.

Honeybees add another layer of sophistication. When a swarm needs a new home, scout bees perform waggle dances indicating both direction and quality of potential nest sites. But they also use "stop signals" - physical vibrations that suppress dances for inferior sites. This dual system of positive promotion and negative suppression creates competing feedback loops that converge on consensus. The best site eventually attracts the most dancers and receives the fewest stop signals, and the swarm moves as one to claim it.

Both ant trails and bee dances show that collective decisions can exceed individual accuracy when proper feedback mechanisms exist. The group becomes smarter than its smartest member.

The evolutionary advantages of decentralized decision-making show up across nearly every animal group that's adopted it.

Predator avoidance tops the list. When citizen scientists tracked over 3,000 starling murmurations, they reported raptor attacks on about one-third of the flocks. But most birds survived because murmurations confound predators through dense, rapidly shifting patterns. A peregrine falcon relies on locking onto a single target and pursuing it with precision. When hundreds of birds twist in coordinated waves, that lock becomes impossible to maintain.

Individual risk drops dramatically in groups. Researchers found that a sparrow in a flock of 50 faces half the predation risk of a solitary bird. The dilution effect is simple math: if a hawk can only catch one sparrow, your odds of being that sparrow decrease with every additional bird in the flock.

Energy conservation matters for migrants. Geese flying in V-formation save up to 30% of their energy compared to solo flight. The bird at the front works hardest, breaking air resistance for those behind. Leadership rotates, with tired birds dropping back and rested ones taking the lead. No goose decides the rotation schedule - individuals simply respond to their own fatigue and the gap at the front, and the system self-organizes.

Information sharing creates collective intelligence that outperforms individual knowledge. When starlings gather in roosts of tens of thousands, they're essentially pooling information about food sources scattered across dozens of square miles. A bird that found nothing today can follow more successful flock-mates tomorrow, reducing wasted foraging time for everyone.

Robustness might be the biggest advantage. Centralized systems fail when the leader dies or makes mistakes. Decentralized networks have no single point of failure. Remove any individual from a murmuration or school, and the group barely notices. The same principles that coordinate a million starlings work just as well for a hundred. This scalability means the coordination mechanism doesn't need to change as groups grow or shrink.

What animal collectives achieve is true emergence - properties that exist at the group level but not in any individual. No single starling understands murmuration dynamics, yet together they generate intelligence that solves navigation and predator evasion in real time.

What animal collectives achieve is true emergence - properties that exist at the group level but not in any individual. No single starling understands murmuration dynamics. No locust grasps swarm trajectories. Yet together, following simple rules about neighbors and spacing, they generate intelligence that solves navigation, predator evasion, and resource allocation problems in real time.

Engineers noticed. If animals can coordinate swarms without central control, why can't robots?

The answer: they can, and they're starting to. Swarm robotics applies principles from flocking birds and schooling fish to the deployment of autonomous vehicles. Instead of programming each drone with a complete flight plan, you give each one simple rules: maintain spacing from neighbors, match their heading, avoid obstacles. The swarm behavior emerges from those individual instructions.

This approach scales brilliantly. Coordinating ten drones centrally is manageable. Coordinating a thousand becomes a computational nightmare - too many positions to track, too much data to transmit, too many decisions bottlenecked through a single controller. But if each drone only tracks its six or seven nearest neighbors, the communication load stays constant no matter how large the swarm grows. You can deploy ten thousand drones as easily as ten, at least in terms of coordination architecture.

Military and commercial applications are already in development. Autonomous underwater vehicles using fish schooling algorithms can survey ocean floors in coordinated grids without constant communication with a base station. Aerial drones can search disaster zones using murmuration-inspired patterns that ensure complete coverage without overlap. Warehouse robots navigate around each other using ant-inspired pheromone-like markers (digital, in this case) to optimize paths to picking stations.

The locust research offers newer possibilities. Ring attractor neural networks - the same circuits locusts use to integrate directional bearings - are being tested in navigation systems that don't require GPS. If a robot can track bearings to nearby landmarks or teammates and let those signals compete through neural-like consensus, it can navigate environments where satellite positioning fails: underwater, underground, indoors, or in hostile signal-jamming scenarios.

Ant colony optimization algorithms already route data through internet networks, finding efficient paths through millions of possible routes just like ants find shortest trails to food. When a data packet moves successfully through a node, it leaves a digital "pheromone" that makes that route slightly more attractive to future packets. Congested routes receive fewer successful traversals and gradually become less favored. The network optimizes itself continuously without any central traffic controller.

Cloud computing platforms use similar self-organizing principles to distribute workloads. Instead of a master server deciding which processor handles each task, individual computing nodes respond to local conditions - their current load, nearby node status, task queue lengths - and the optimal distribution emerges from thousands of small decisions.

The principles governing animal collectives challenge some deeply embedded assumptions about how coordination works.

We tend to think leadership is necessary for group coordination. Animal collectives prove it isn't. We assume complex outcomes require complex instructions. Three simple rules generate murmuration complexity. We believe intelligence requires individual understanding of the whole system. Starlings create collective intelligence while each bird knows only its immediate neighbors.

This has implications beyond robotics. Self-organization principles appear in human systems too - markets, traffic patterns, crowd movements, even the emergence of language and culture. When you drive, you're not following orders from a traffic authority every second. You're applying simple rules (maintain spacing, match speed, avoid collisions) that generate traffic flow patterns visible from space. Those patterns can be smooth or gridlocked depending on density and individual behavior, but they emerge without anyone orchestrating them.

Urban planners increasingly think about cities as self-organizing systems rather than top-down designs. Pedestrian desire paths - those worn trails that appear where sidewalks don't quite go - show where people actually want to walk, information that no planner could predict but emerges clearly from thousands of individual route choices. Smart cities that respond to real-time foot traffic, vehicle flow, and crowd density are essentially implementing murmuration principles at urban scale.

Some researchers study collective human decision-making through the same lens as fish schools or bee swarms. When do crowds become wiser than experts? When feedback mechanisms allow information sharing without centralized filtering. When does groupthink lead to disasters? When positive feedback loops (everyone following everyone else) lack the negative feedback that would brake runaway consensus. The mathematics of quorum rules and information cascades applies whether you're modeling fish choosing which direction to swim or investors deciding which stocks to buy.

The challenge is identifying when decentralized coordination outperforms hierarchy and when it doesn't. Animal collectives excel at tasks requiring rapid adaptation to changing conditions, robustness against individual failures, and scalability across group sizes. They struggle with tasks requiring long-term planning, specialized division of labor, or coordination toward goals that conflict with individual incentives.

Understanding these boundaries helps designers choose the right coordination model. A search-and-rescue swarm might use murmuration rules to cover territory efficiently. A construction project still needs architects and project managers because building a bridge requires specialization and planning that simple local rules can't generate.

What makes collective animal behavior so captivating is the gap between what it looks like and how it works. Murmurations appear choreographed, as if someone's directing the performance. Locust swarms seem like unified organisms with singular purpose. Fish schools flow like liquid metal, bending around predators with impossible coordination.

The truth is stranger than the illusion. There's no choreographer, no unified organism, no coordination beyond each individual following simple rules about the few neighbors it can perceive. Order arises not from planning but from iteration - millions of tiny adjustments, happening every fraction of a second, creating patterns that exist only at the level of the whole.

Scientists now recognize this as one of nature's fundamental principles: self-organization, where overall order emerges from local interactions without external control. It appears in crystal formation, chemical reactions, weather patterns, brain activity, ecosystems, and social systems. Animal collectives just make it visible in ways that stop you on an evening walk when thousands of starlings darken the sky above you in impossible formations.

In 2013, physicists at Princeton simulated starling synchronization and found the information moving through murmurations propagates with almost no noise degradation. In systems theory terms, the flock achieves a signal-to-noise ratio that approaches theoretical limits. Each bird's movement contains signal (useful directional information) and noise (individual variation). Yet as that information passes through overlapping networks of seven-neighbor clusters, the signal amplifies while noise cancels out.

This is collective intelligence in its purest form. Not the intelligence of individual genius, but the intelligence of interaction - simple components following simple rules, generating sophisticated outcomes that none of them could achieve alone. It's the hidden democracy of nature, where votes are cast continuously through movement and position, where every individual has equal influence within its neighborhood, and where decisions emerge from consensus without anyone calling for a vote.

The next time you see birds wheel across a sunset sky or fish shimmer through shallow water, you're not watching a performance. You're witnessing emergence - order from chaos, intelligence from rules, democracy without debate. No leader, no plan, no individual understanding the whole. Just thousands of creatures doing what evolution taught them: watch your neighbors, follow simple rules, and trust that the pattern will emerge.

It always does.

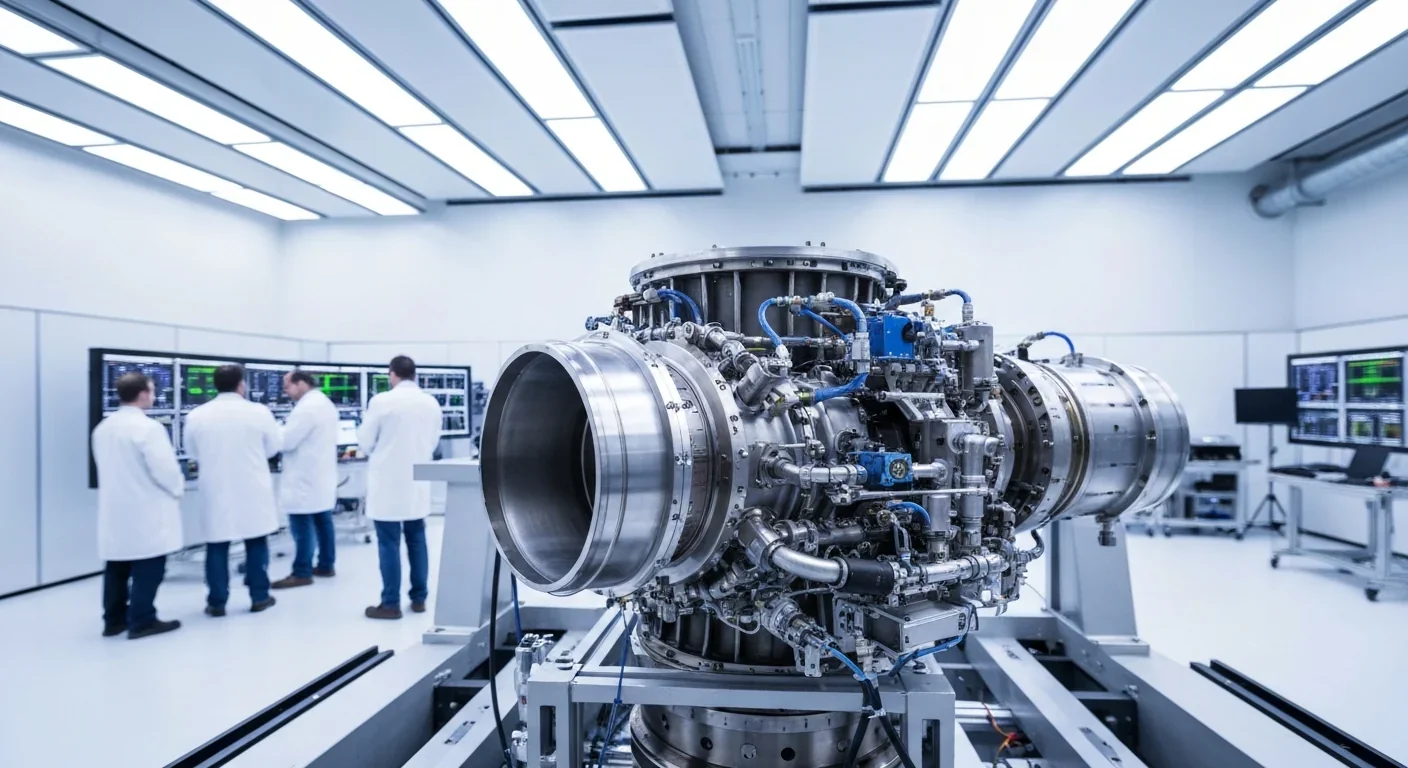

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

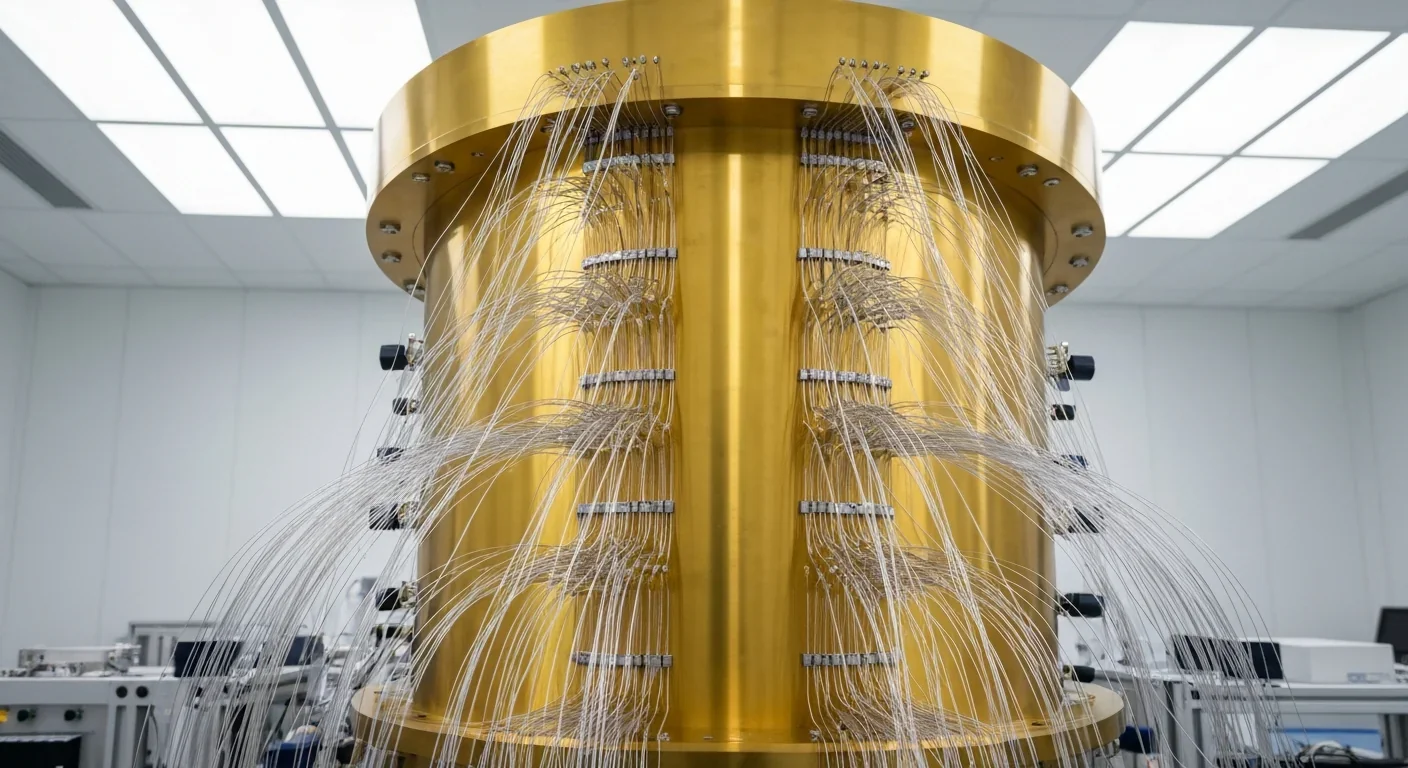

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.